Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Background of Recorded Blues By Max Haymes

This is the fourth of a series of short surveys on the content and meaning of some early blues which takes in the social, economic and cultural strands of the life-situation for Blues singers in the first decades of the 20th century. The appreciation of some titles will also be included. The early Blues, at its highest level, is art (working-class art) every bit as much as say the works of Picasso or Beethoven. Indeed, in a hand-out on one of the courses I teach, I hailed Charlie Patton as "the Beethoven of the Blues".

No. 4 P.C. Railroad Blues - Charlie Taylor & The New Orleans Nehi Boys.

If most explorations in the background of early blues has, by definition of the timescale, to include varying degrees of speculation; then this title is totally speculative! Unique in this series insofar as although issued by Paramount (Para 13121) this side has never been found. B. & G.R. give no matrix no. although they note that on the reverse of 13121 is alleged to be "You've Got What I Want" by Irene Scruggs. This being the first of 2 versions by the vaudeville-blues singer, the other one came out on Gennett some 3 months later. I use the word `alleged' advisedly, as Dixon & co. state that "It has not been possible yet to check Paramount 13121 to see whether it is pressed from master L-348. The exact recording date came from a test pressing of matrix L-348 in the possession of Ms. Scruggs." (1). But by "1980 the test's whereabouts were unknown." (2). Test pressings, it should be born in mind, are generally a one-sided disc. This date is "Wednesday, 28 May 1930" (3) and recorded in Grafton, Wisconsin. (Although by 2003 it seems "Scruggs may easily have been recording around May 23." (4)). Whereas the flip-side (if it is so) by Charlie Taylor is listed as being recorded c. December 1929 (However, it now transpires that via some astute detective work, author Alex van der Tuuk claims that the New Orleans Nehi Boys, along with Charlie Taylor, Ishmon Bracey, and Tommy Johnson "may have been recording between December 10 and 17, 1929." (5).) at the same location. Dixon and co. relate "that the instrumentation is uncertain" (6). This is given as: "Charles Taylor, v; acc. New Orleans Nehi Boys: prob. `Kid' Ernest Moliere cl; prob. own p; prob. Ishman Bracey and/or Tommy Johnson g." (7)

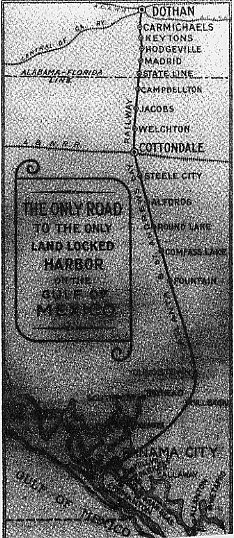

In

any event, the initials 'P.C.' puzzled me for several years as I had not come

across a Southern railroad that fitted them. My first thoughts were to do with

the Atlanta & St. Andrews Bay Railway. This was usually referred to as "The Bay

Line" but also sometimes as the "Panama Canal Route". The A. & St. A.B. starting

in 1908 did well conveying lumber and turpentine as well as passengers. But by

1929 the line was struggling to survive as the Great Depression loomed. However,

this all changed dramatically when a great opportunity for black employment

appeared on the scene when the "Southern Kraft Division of International Paper

Company announced that it would build the first paper mill in Florida at Panama

City." (8). Indeed, Panama City as the southern terminus of the A. & St. A.B. Ry.

might have been the 'P.C.' in Charlie Taylor's blues. The Bay Line or P.C. route

connected with the Atlantic Coast Line at Dothan, Ala. In turn the A.C.L. ran to

Tuscaloosa, Ala. where Taylor could change over to the Mobile & Ohio back to his

Mississippi home (and vice-versa, of course).

In

any event, the initials 'P.C.' puzzled me for several years as I had not come

across a Southern railroad that fitted them. My first thoughts were to do with

the Atlanta & St. Andrews Bay Railway. This was usually referred to as "The Bay

Line" but also sometimes as the "Panama Canal Route". The A. & St. A.B. starting

in 1908 did well conveying lumber and turpentine as well as passengers. But by

1929 the line was struggling to survive as the Great Depression loomed. However,

this all changed dramatically when a great opportunity for black employment

appeared on the scene when the "Southern Kraft Division of International Paper

Company announced that it would build the first paper mill in Florida at Panama

City." (8). Indeed, Panama City as the southern terminus of the A. & St. A.B. Ry.

might have been the 'P.C.' in Charlie Taylor's blues. The Bay Line or P.C. route

connected with the Atlantic Coast Line at Dothan, Ala. In turn the A.C.L. ran to

Tuscaloosa, Ala. where Taylor could change over to the Mobile & Ohio back to his

Mississippi home (and vice-versa, of course).

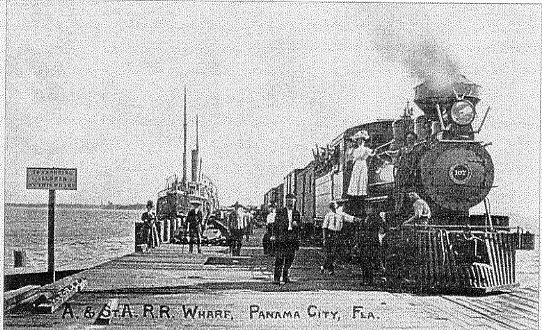

freight train of the A. & St. A.B. R.R. (sic) at Panama City. Fla. c.1909.

However, I was more inclined to think that 'P.C.' might refer to Pullman cars which employed black porters almost exclusively. The latter existed very much on tips from passengers as their salary from the Pullman Co. was derisory bordering on the invisible! This was to be a contributing factor in the 1894 Pullman strike. Then I came across the Parlor Car, which usually appeared on Pullman trains.

Both the parlor car and the dining car were the offshoots of the sleeper and drawing room car. The latter being popularised, but not originated, by George Pullman. The parlor car in the 1920s and around the time Charley Taylor recorded "P.C. Railroad Blues" had achieved a sumptuous interior. As early as 1892 on the Chicago & Alton "The 64-foot-long parlor cars had 16 revolving chairs and 6 wicker seats. Their interiors were trimmed in bronze with schemes of ivory, light green, rose pink, white mahogany, and light gold accents. The new first class equipment was added to the company's premier overnight Chicago-St. Louis train, the Lightning Express," (9). Maybe Taylor was having a dig at the parlor car which would not generally be accessible to Southern blacks and was the complete antithesis of the Jim Crow (segregated) Or baggage and

Jim Crow car on the S.A.L. Tar River Line at Boykins

Va. in

1934. "White section on left, Baggage at center, while right section was

reserved exclusively for Colored passengers..."

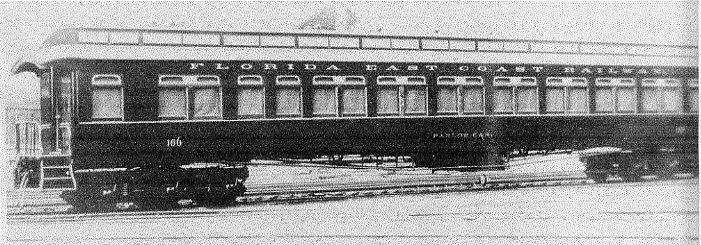

combination cars that they were normally forced to travel in when in the South. The cars described on the C. & A. were standard for Pullman and appeared on the Southern, L. & N. and other Southern roads, including the Illinois Central. By 1911 the I. C. was featuring sun-parlor cars which later ran on the Panama Limited'. The legend "Parlor Car" was often featured on the side of the car. (see pic.).

Parlor Car of the Florida East Coast Railway c.1895.

By the 1920s the `railway' "designation had been removed."

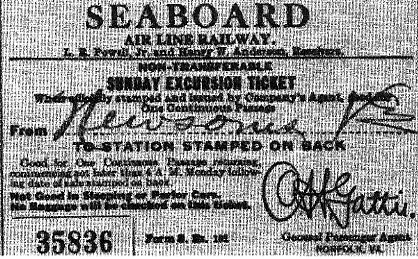

To make sure that blacks would not be able to ride in the Parlor Cars, the Seaboard Air Line Railway specified that their excursion tickets (so popular with blacks) were "Not Good in Sleeping or Parlor Cars" (10).

Seaboard Sunday Excursion ticket issued in August 1933 costing about 1c. per

mile.

All the foregoing is completely speculative unless a copy of Charley Taylor's record turns up, and I welcome any other views as to what "P.C. Railroad Blues" is all about.

Max Haymes, September 2004

Notes

| 1. Dixon R.M.W. J. Godrich & H. Rye. | p.783. |

| 2. Tuuk van der A. | p.193. |

| 3. Dixon & co. | Ibid. |

| 4. Tuuk. | Ibid. p.171. |

| 5. Ibid. | |

| 6. Dixon & co. | Ibid. p.894. |

| 7. Ibid. | |

| 8. Cline W. | p.236. |

| 9. Glendinning G. V. | p.122. |

| 10. Prince R.E. | p.225. |

References

|

1. Dixon Robert M.W. John Godrich

& Howard Rye |

"Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943".4th. ed. (Rev.). Clarendon Press. Oxford 1997. |

| 2. Tuuk van der Alex. | "Paramount's Rise And Fall". (A History Of the Wisconsin Chair Company and its Recording Activities). Mainspring Press. 2003. |

| 3. Cline Wayne. | "Alabama Railroads". The University of Alabama Press. 1997. |

| 4. Glendinning Gene V. | "The Chicago & Alton Railroad" (The Only Way). Northern Illinois University Press. 2002. |

| 5. Prince Richard E. | "Seaboard Air Line Railway". Indiana University Press. 2000. (Rep). l". pub. 1966. |

Illustrations

| 1. Cline. | Ibid. p.237. |

| 2. Ibid. | p.236. |

| 3. Prince. | Ibid. |

| 4. Bramson Seth H. | "Speedway To Sunshine" (The Story Of The Florida East Coast Railway). The Boston Mills Press. 2003. (Rev. ed.). 1st.pub. 1984. |

| 5. Prince. | Ibid. |

Essay © Copyright 2004 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Website © Copyright 2000-2006 Alan

White. All Rights Reserved.

Check out the other essays in the "Background of Recorded Blues" series:

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 1 - Pea Vine Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 2 - Mobile and Western Line

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 3 - Beaver Slide Rag

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 5 - Nut Factory Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 6 - Big Ship Blues