Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Background of Recorded Blues By Max Haymes

This is the fifth of a series of short surveys on the content and meaning of some early blues which takes in the social, economic and cultural strands of the life-situation for Blues singers in the first decades of the 20th century. The appreciation of some titles will also be included. The early Blues, at its highest level, is art (working-class art) every bit as much as say the works of Picasso or Beethoven. Indeed, in a hand-out on one of the courses I teach, I hailed Charlie Patton as "the Beethoven of the Blues".

No. 5 Nut Factory Blues - Hi Henry Brown. 1932.

In 1992, Chris Smith wrote that ‘Hi' Henry Brown "was an unmistakeable musician... with a vinegary voice, and - in song, at least - a correspondingly sour disposition, which he turned on pimps, prostitutes, preachers, and even the passengers on the Titanic; (1). In the case of the prostitutes I would suggest he has the wrong slant on what Brown is singing about. In fact this side is more of a protest against mistreatment of black women and the general situation (in 1932) where many were paid such a low wage (or "nothin' at all") that they were forced on to the streets -a sad and very familiar scenario down through the ages in all societies.

‘Hi' Henry Brown, like his namesake Henry Brown the better-known blues pianist, was a resident of St. Louis for at least some of his adult life. Apart from possibly being originally from Pace, Miss. little else is known about him. In the largest migration of blacks from the South which "began about 1910 and rose to great heights between 1916 and 1919." (2), most headed for the "industrial cities of the North and Middle West." (3). Five of the 10 cities listed as the "most important" are in the latter area and the increase in the black population of St. Louis between 1910 and 1920, which was 58.9%, was only surpassed by that of Indianapolis with 59% for the same period. (4). And like Indianapolis, St. Louis spawned a thriving blues community in the late 1920s and '30s, including ‘Hi’ Henry Brown.

Although these industrial centres gained a growing trade union movement within the factories and (in St. Louis) along the levee, they were largely exclusive of black membership.The A.F.L. (American Federation of Labor), the U.S. counterpart of Britain's T.U.C., had made few gains "in the area of interracial organising" in the 1930s. What progress was made was inspired (?) by "a sense of competition with its rebellious stepchild, the Congress of Industrial Organisations". (5). The C.I.O. was to break away "from the parent body in 1935". (6). But prior to this event "At last some black communities threw their support behind union activities for the first time, impressed with the relative openness of C.I.O. policies and with the uncompromisingly egalitarian rhetoric of the Communist Party". (7). One of the "several dramatic, successful organising drives that made full use of black women's leadership abilities (included) the St. Louis nutpickers strike against "Boss Funsten" in 1933". (8). Jesse Morgan Hill Funsten (b. 1891) went by the nickname of "Boss"..." (9). and came up against "Connie Smith and 3,000 nut pickers, 85 percent of whom were Black women, (who) organised the Food Workers' Industrial Union, a C.I.O. affiliate in St. Louis". (10). Surprisingly, the all-powerful, white "Boss Funsten" didn't get his own way on this occasion, when ‘battling' with his multi-racial unskilled workers. In a divide and rule attempt he "failed to break the interracial strike by offering white operators more money if they returned to work, marking a departure in management's traditionally successful manipulations of the racial caste system." (11). This was probably in part due to the growing support by workers (at that time) for the FW.I.U. and also because the white women tempted by Funsten were sure to be very aware of being a small minority, representing only 15% of the nut picker workforce.

But 'Hi' Henry Brown was way ahead of this strike action. In the previous year of 1932 he recorded what can only be deemed a thinly-veiled protest in the form of his "Nut Factory Blues" which featured his superb, harsh vocal and almost supernatural twin-guitar accompaniment with Charlie Jordan, who was also a St. Louis inhabitant.

"Down

on Deep Morgan, just about Sixteenth Street;

Way down on Deep Morgan, just about Sixteenth Street.

Well, they tendin' their business where the women do meet."

"Down in the basement when they work so hard;

Well, it's down in the basement when they work so hard.

Well, it's out on the corner, they husbands ain't got no job."

(12)

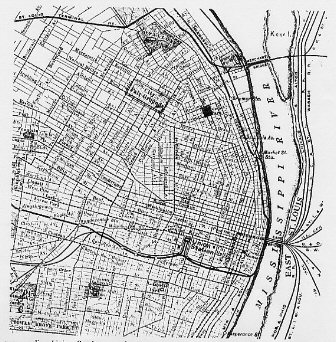

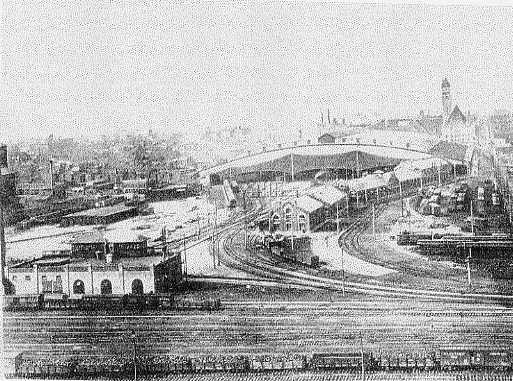

Sixteenth Street ran alongside the tracks of the freight yard just east of the sprawling St. Louis Union Station northward, crossing Morgan Street (Deep Morgan) and Franklin Avenue which headed from west to east (along with Market and Biddle Streets) down to the levee on the Mississippi River near the Eads Bridge. In 1894, when St. Louis Union Station was opened, it was stated that the "neighborhood

Map of St. Louis downtown area in 1904 - the year of the World's Fair at St. Louis.

surrounding Union Station was frankly inelegant with tawdry saloons, cheap hotels,penny arcades, and other assorted eyesores lacing the entire area". (13). Not surprisingly this was in the black sections of town and also the poorest and most overcrowded, where around one-third of the population (predominantly black) by 1920 lived "between railroad tracks and under the shadow of factories". (14). This quote is part of a St. Louis Church survey conducted over a period from 1899 up to 1920. For the purpose of this exercise the administrators divided up the sections or

View of

St. Louis Union Station looking north. Sixteenth Street is on the right.-early

1895.

‘Districts' of the city and graded them according to prosperity, environment, housing, church membership, and attendance, etc. District III - 'Downtown' is labelled "The Worst" on all counts and "contains the transportation terminals, both river and rail, - the docks, bridges, railroad yards and Union Station, also the wholesale and storage businesses which go with the transportational terminals." (15).

Most of the factories in St. Louis (as with most Southern cities at the time), either banned trade unions or the latter where they were tolerated were nearly all controlled by the white craft unions which refused blacks membership. Many workers, and particularly women, therefore had no redress with their employers who could not only 'hire and fire' at will; but also dictate wages and conditions. Often, as elsewhere in the world of the unskilled industry, a fixed wage was not implemented. Instead, the scurrilous 'piece-work' system was utilised. At worst, this system set a target of production for the workers (often unrealistically high) which had to be achieved before they actually earnt any money! As ‘Hi' Henry Brown sings so feelingly, when it comes to pay-day on the Saturday.

"Saturday evenin', when they draw their pay;

Onnnn! Saturday evenin', when they draw their pay.

When they don't draw nothin', their husbands will drive them away."

But often these over-worked, under-paid women were physically abused by their unemployed husbands, as well. Somehow, illogically, blaming their wives rather than direct their anger at the nut factory management (including "Boss Funsten") for exploiting the female workers.

"Some

draw a check babe, some draw nothin' at all'

Well, some draw a check, Lord, some draw nothin' at all.

When they don't draw nothin', their husbands bust them in the jaw."

(16)

So, very often these black female workers would have ‘everybody down on me' - mis-treated at the factory and at home. At least, before the C.I.O.'s Connie Smith helped them form the Food Workers Industrial Union in 1933.

But before this event, these workers were sometimes literally forced out on to the streets in a desperate bid to get some income for themselves and their families. Often working the dangerous, unlit and unpaved alleys between the streets such as Morgan or Market Street as well as Franklin Avenue. The 'jelly beans' (pimps) major problem was keeping track of the customers or "tricks" that their "good girls" would pick up.

"Down

on Franklin Avenue, jelly beans standin' to an' fro;

Aaaah! Down on Franklin Avenue, jelly beans standin' to an' fro.

Well, you hear one jelly bean ask the other one: "Which-a way did my good girl

go?". (17).

The

Pennsylvania RR. mail train, Spirit of St. Louis approaching St. Louis Union

Station on Aug. 19 1932 - some 6 months after 'Hi' Henry Brown recorded "Nut

Factory Blues".

Notes

| 1 | Smith C. | Notes to Document CD |

| 2 | Spero S.D. & A.L. Harris. | p.151. |

| 3 | Ibid. | |

| 4 | Ibid. | |

| 5 | Jones J. | p.212. |

| 6 | Ibid. | |

| 7 | Ibid. | p.p.212-213. |

| 8 | Ibid. | p.213. |

| 9 | Funsten Forbes F. | |

| 10 | Hine D.C., E.B. Brown, R. Terborg-Penn. | p.686. |

| 11 | Ibid. | |

| 12 | "Nut Factory Blues" | 'Hi' Henry Brown vo.gtr.; Charlie Jordan gtr. 17/3/32. New York City. |

| 13 | Grant R., D.L. Hofsommer, O. | p.18. |

| 14 | Douglass H.P. | p.78. |

| 15 | Ibid. | p.238. |

| 16 | "Nut Factory Blues" | Ibid. |

| 17 | Ibid. |

Illustrations

| Grant, Hofsommer & Overly. | Ibid. |

References

| 1 | Smith Chris. | Notes to "Charley Jordan Vol. 2" Document DOCD-5098. 1992. |

| 2 | Spero Sterling D. & Abram L. Harris. | "The Black Worker"(The Negro and the Labor Movement). Atheneum. New York. 1974. (Rep.). 1". pub. 1931. |

| 3 | Jones Jacqueline. | "Labor Of Love, Labor Of Sorrow"(Black Women, Work & The Family, From Slavery To The Present). Vintage Books. New York. 1995. (Rep.). 1". pub. 1985. |

| 4 | Funsten Forbes Florence. | Google website. 25th. Feb. 2003. |

| 5 | Hine Darlene Clark, Elsa Barkley Brown, Roselyn Terborg-Penn. | "Black Women In America"(An Historical Encyclopedia). 2 Vols. Indiana University press. 1994. (Rep.). 1``. pub. 1993. |

| 6 | Grant Roger, Don L.Hofsommer, Osmund Overly. | "St. Louis Union Station"(A Place For People A Place For Trains). The St. Louis Mercantile Library. St. Louis. 1994. |

| 7 | Douglass H. Paul. | “The St. Louis Church Survey” (A religious Investigation With A Social Background). George H. Doran Co. New York. 1924. |

| 8 | Transcriptions by Max Haymes. | |

| 9 | Discographical details from "Blues& Gospel Records 1890-1943". 4". ed. rev. John Godrich, Robert M.W. Dixon, Howard W. Rye. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1997. |

Essay © Copyright 2005 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Website © Copyright 2000-2006 Alan

White. All Rights Reserved.

Check out the other essays in the "Background of Recorded Blues" series:

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 1 - Pea Vine Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 2 - Mobile and Western Line

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 3 - Beaver Slide Rag

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 4 - P.C. Railroad Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 6 - Big Ship Blues