Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Background of Recorded Blues

By Max Haymes

This is the second of a series of short surveys on the content and meaning of some early blues which takes in the social, economic and cultural strands of the life-situation for Blues singers in the first decades of the 20th century. The appreciation of some titles will also be included. The early Blues, at its highest level, is art (working-class art) every bit as much as say the works of Picasso or Beethoven. Indeed, in a hand-out on one of the courses I teach, I hailed Charlie Patton as "the Beethoven of the Blues".

No. 2 Mobile And Western Line - State Street Boys, 1935.

Like No. 1, this is a blues about a railroad and features a small group in the 1930s led by, on this occasion, William McKinley `Jazz' Gillum. The latter was the first harmonica player in Chicago to record. Indeed, he had been in the Windy City more than a decade prior to the arrival of John Lee `Sonny Boy' Williamson. Vastly underrated by most Blues historians/writers, Jazz Gillum is only now getting belated recognition as a performer of the highest order. Although referred to as an urban singer, he often stayed more faithful to the rural or downhome blues than several of his contemporaries, including Sonny Boy who was actually some ten years younger.

Jazz Gillum made his record debut in 1934 and the following year he joined Big Bill Broonzy (who backed him regularly from 1934 onward) and famed pianist Black Bob, for a small group of recordings as the "State Street Boys". Big Bill and an unknown sharing the vocals. State Street of course was home to thousands of blacks on Chicago's Southside in the 1920s and `30s - as it is today. To add to the `country feel' of the session in January, 1935, Big Bill sometimes switched to his first-learned instrument - the fiddle. Or else the obscure Zeb Wright was brought in to play it.

"Mobile And Western Line" (Vo 03131) was the first of 8 sides and the opening and closing verses led me to think that Gillum spent some time in the earlier (and uncharted) part of his life in the state of Alabama.

"Have

you ever looked down that Mobile an' Western line?

Have you ever looked down the Mobile an' Western line?

An' your plumb good woman keep-a rollin' across your mind."

"I

got the rickets, got the rackets, got the Mobile-Birmingham blues;

I got the rickets, got the rackets, got the Mobile-Birmingham blues.

Spoken; "Yeah, man!"

I got the blues so bad baby, I don't know what to do."

(1)

The last verse was adapted from "Old Rock Island Blues" (Co 14440-D) by banjoist Lonnie Coleman in 1929, who sings "got the Mobile blues". Black Bob's intro. giving a distinct urban feel until Gillum kicks in with some lovely low-down wailing harp which goes right back to the country. Big Bill playing tasteful but unobtrusive guitar while the thumping double-bass (Bill Settles?) and the unidentified `slow scat' singer presumably gave this blues its "Hot Dance Acc." description on the Vocalion record label. This credits "Bill Gillam" as the song writer.

As Jazz Gillum was born in Mississippi (1904) and left for Chicago in 1923 (2) it would be reasonable to assume a location within the Magnolia State for the M. & W. Harris does not report that the harp player strayed outside Mississippi until he boarded a north-bound train for Chicago. There is even a Mississippi railroad that nearly fits the bill and the State Street Boy's title: the Mobile & Northwestern RR. This was a local road in the Delta which ran from Dowd's Landing (on the Mississippi) River) in Coahoma County to Clarksdale. Started in 1873 it struggled for years to keep solvent (3) and was finally taken over by the Mobile, Jackson & Kansas City RR. on "Feb. 20, 1890" (4). The M.J. & K.C. was later absorbed by the Gulf, Mobile & Northern (G.M & N.) which in 1940 merged with the Mobile & Ohio (M. & O) to form the G.M. & O.

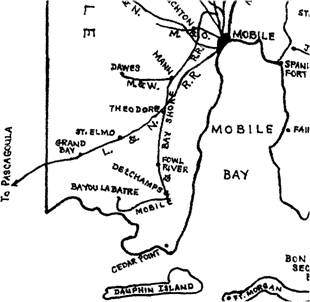

It is the M. & O. which maintains the Mobile & Western (a logging road) in the State Street Boy's song. Our story goes back to March 1st 1906, when the Mann Lumber Co. was "incorporated in Mobile County, Alabama, . . . Their sawmill was built at St. Louis, Alabama, about 13 miles southwest of downtown Mobile." (5). To service their sawmill, the lumber company "first established an interchange with the Mobile & Bay Shore Division of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad at the point where the M. & O. line bridged the Dog River. From this interchange point, named Mann, a standard-gauge railroad was laid due westward to St. Louis. This 3˝ miles of fine was incorporated in September 1906 as the Mobile & Western Railroad." (6). This was a common carrier (passenger & freight) line. Mann also built "about four more miles of private logging trackage to the northwest from the sawmill at St. Louis through the Dawes community". (7). But in this same month of September a major hurricane devastated the west side of Mobile Bay including "the tracts owned by Mann Lumber Company." (8). They went bankrupt and the M. & W. was first sold to the Union Naval Stores Company "in April 1907...". It was to be sold again in November 1909 to the M. & O. In 1912 the M. & O. "even went back in and rebuilt the line of track between St. Louis and Dawes. The entire eight miles of railroad was then operated as an industrial branch by the M. & O. into the late 1930s." (9). So Jazz Gillum and his gang were bang up to date in 1935 with this recording. Even if the line was now called the M. & O. As an "industrial branch" it is far more likely to have retained the `Mobile & Western' tag.

The strongest pointer to Gillum having spent some time living in Alabama is the sheer parochial nature of the M. & W. If Charlie Patton's blues (see No. 1) "are as specifically local as a telephone directory". (10). then Jazz Gillum is being as local on "Mobile And Western Line". This railroad was barely 8 miles long! He had to have stayed in the area served by the M. & W. for a short period at least, as the line would have been too obscure (and too small!) to be known outside a local community.

One attraction to Alabama, apart from getting out of his native state, might have been the readily accessible lumber industry; either to work in or as a forum for entertaining the black workers in the logging camps. One of the largest customers for timber was the Tennessee, Coal, Iron & Railroad Company. The T.C.I. had a "huge ... complex at Fairfield, Alabama," (11). Fairfield being a suburb of Birmingham about 5 miles distant. Lawson elaborates: "The sprawling T.C.I. steel plant, with its coal mines, ore mines and private railroads located west of downtown Birmingham, had an insatiable appetite for mine props (i.e. support beams) railroad ties and other heavy timbers. The steel company even had its own wood preserving plant at Bessemer, Alabama." (12). One company which helped feed this `appetite' was the Bladen Springs Lumber Co. whose "entire production... was committed to the (T.C.I.) ...and the massive plant at Fairfield." (13). In March, 1930, the Bladen Springs Lumber Co. was leased out to a Mississippi concern; the Hutchison Lumber Co. "out of Laurel." (14)

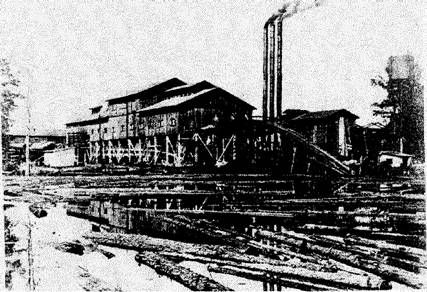

Bladon Springs Lumber Co. plant at Service, Ala.

In 1928.

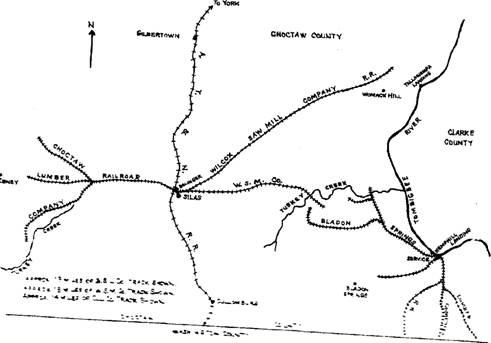

Laurel, Miss. in Jones County, is some 150 miles southeast of Indianola in Sunflower county where Jazz Gillum was born in 1904. He could easily hobo his way (when a teenager) to Laurel and get work at several large logging concerns in the area, including Eastman-Gardiner, Marathon, Wasau, and the Gilchrist-Fordney Lumber Co. (15). Gillum might have got word `on the circuit' of logging work in the Bessemer Birmingham area, or even on the Mobile & Western; by then of course run by the M. & O. Failing a Laurel connection our hero had an alternative almost literally on his door step. The Southern Railway in conjunction with the Columbus & Greenville ran a main line from Greenville, Miss. through Indianola direct to Birmingham on the way to Atlanta, Ga. and beyond to the Eastern seaboard. (16). And another option which might have been considered by Gillum was the Choctaw Lumber Co. in Bolinger, Ala. which "had standard-gauge trains working the Choctaw and Washington County woods all the way to Silas and Yellow Pine." (17). Yellow Pine, Ala. (named after a logging company) was just east of the Miss./Ala. state line and Silas was one of the hamlets served by the Bladon Springs Lumber Co. Or maybe he tried another logging line, the Washington & Choctaw Railway, which opened in June 1916, running from " a connection with the Mobile & Ohio Railroad at Yellow Pine to a connection with the Alabama, Tennessee & Northern Railroad at Bolinger, Alabama." (18). The A.T. & N. then headed north stopping at York, Ala. [First called DAY’S GAP…changed to YORK when the application for a PO (post office) was submitted in 1884,” (19). But due to another York already in Alabama, this was changed "in 1890" (20) to Oakman.] on the way to Reform (on the M. & O.). At York Gillum could catch a train (or ride the blinds) on the Southern heading back to Indianola or Greenville.

An early Alabama home for Jazz Gillum might have a reference in some of his recorded blues. As well as "Mobile And Western Line" he cut a "Birmingham Blues" (BB B7341) as "Bill Gillum And His Jazz Boys" in 1937. His downbeat (reflective?) vocals and personalised detail in the lyric seem to have an autobiographical ring of truth about them.

1.

"It's a

small town they call Bessemer, way down in Alabam. (x 2)

It ain't no great big city, only 12 miles from Birmingham."

2 "Me an' my dirty buddy, me an' my buddy Sam. (x 2)

We used to live in Bessemer, but he moved to

Birmingham."

Spoken: "Play it!

My, my."

3. "I am quiet an' I'm easy. Baby, don't think I'm no lamb. (x 2)

If you want somethin' good, baby. Try

somethin' from Birmingham."

(21)

The second verse implies that Gillum and `Sam' had hoboed their way to Bessemer, maybe looking for work at the T.C.I. wood preserving plant referred to earlier. Riding the blinds/rods was not conducive to maintaining personal hygiene and of course you slept in your clothes which soon got dirty as well. The closing line appears to see a break-up between the two with Sam moving to the Magic City, as Birmingham was sometimes known. Perhaps he was a long-time friend or `best mate’ [This could be the same drinking partner ("we can drink more whiskey, ooh well, well! than a thousand men") who is by then possibly dead, that Jazz Gillum sings of so movingly on "Me And My Buddy" in 1941].The third verse could be translated as Gillum claiming to a prospective (?) girl friend that while he is a sexual partner worth considering, Sam had a way with the ladies that was "somethin' good".

From the same session came "My Old Suitcase" (BB B7253) which included verses referring to the "rolling mill" and the "old mill whistle"; invoking Alabama's premium harp blower Jaybird Coleman and his "Mill Log Blues" (Ge 6226) from 1927. While Gillum's "I'm That Man Down In The Mine" (BB B7718) was made in 1938; his last year of recording in the pre-war era.

Jazz Gillum c. 1937

Most of the foregoing `evidence' would be deemed circumstantial at best. Yet there is "Mobile And Western Line" with its essentially local references. Taking the lyrics and titles discussed, as a whole, they seem to indicate a very real possibility that a young Jazz Gillum (still in his teens) spent some time in the state of Alabama as a resident; as a logging and/or mine worker and blues singer playing for nickels and dimes on the street corners of Bessemer or at the mining and logging camps in the central and south-western part of the state.

I am heavily indebted to a truly remarkable tome on

logging railroads in Alabama by Thomas Lawson Jr.

Also many thanks to collector Paul Swinton

for supplying the label shot of "Mobile And Western Line''.

|

Notes |

||

| 1. | "Mobile And Western Line" |

State Street Boys: Jazz Gillum vo.hca.speech; Black Bob pno.; Big Bill

gtr.;unk. 2nd. vo.; unk. male speech. 10/1/35. Chicago, Ill. |

| 2. | Harris S. | p.193. |

| 3. | Willis J.C. | p. p.94-96. |

| 4. | Cline W. | p..p.184-185. |

| 5. | Lawson T. | p.187. |

| 6. | Ibid. | |

| 7. | Ibid. | |

| 8. | Ibid. | |

| 9. | Ibid. | |

| 10. | Russell T. | p.42. |

| 11. | Lawson | Ibid. p.69 |

| 12. | Ibid. | p.p.69-70. |

| 13. | Ibid. | |

| 14. | Ibid. | p.71. |

| 15. | Hickman N. | p.179. |

| 16. | Cline | Ibid. p.133. |

| 17. | Ibid. | p.230. |

| 18. | Lawson | Ibid. p.200. |

| 19. | Foscue V. | p.103. |

| 20. | Ibid. | |

| 21. | "Birmingham Blues" | Bill Gillum And His Jazz Boys: Jazz Gillum vo.hca. speech; prob. Blind John Davis pno.; Big Bill gtr.; unk. dins. 11/10/37. Leland Hotel, Aurora,111. |

|

References |

|

| l. Harris Sheldon | "Blues Who's Who". Da Capo. 1989. (Rep.). 1st.pub. 1979. |

| 2. Willis John C. | "Forgotten Time" (The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta after the Civil War). University Press of Virginia. 2000. |

| 3. Cline Wayne. | "Alabama Railroads". The University of Alabama Press. 1997. |

| 4. Lawson Jr. Thomas. | "Logging Railroads Of Alabama". Cabbage Stack Publishing. 1996. |

| 5. Russell Tony. | "The Blues" (from Robert Johnson to Robert Cray). Carlton Books. 2000. |

| 6. Hickman Nollie. | "Mississippi Harvest" (Lumbering In The |

| Longleaf Pine Belt 1840-1915). University of Mississippi. 1962. | |

| 7. Foscue Virginia O. | "Place Names In Alabama". University ofAlabama Press. 1989. |

Discographical detail

from "Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943". 4th, ed. (Rev.).

Robert M.W. Dixon. John Godrich.

Howard W.

Rye. 1997.

Corrections/additions

by Max Haymes.

Transcriptions by Max Haymes.

Illustrations

| 1. Swinton Paul. | Reproduced with permission. |

| 2. Lawson | Ibid. |

| 3. Ibid. | p.70. |

| 4. Ibid. | p.71. |

| 5. Fremeaux (2 x C.D.) | "The Blues". (Jazz Gillum 1934-1947). FA 260. 1998. |

Discography

| Mobile And Western Line | B.O.B.-4. "Bill Jazz Gillum (1935-1946)". L.P. c. 1985. |

| Birmingham Blues | Document DLP 522. "Jazz Gillum 1935-1947".L.P. 1988. |

Note: Both titles are on Document C.D.s. "Mobile And Western" on Big Bill Broonzy Vol.3(1934-1935) on DOCD-5052 and "Birmingham Blues" is on Jazz Gillum Vol. I on DOCD-5197. The latter CD also includes "I'm That Man Down In The Mine" and "My Old Suitcase", referred to in the text.

Record label abbreviations on original issues

BB=Bluebird

Co=Columbia

Ge=Gennett

Vo=Vocalion

Max Haymes, August 2004

Essay © Copyright 2004 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Website © Copyright 2000-2006 Alan

White. All Rights Reserved.

Check out the other essays in the "Background of

Recorded Blues" series:

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 1 - Pea Vine Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 3 - Beaver Slide Rag

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 4 - P.C. Railroad Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 5 - Nut Factory Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 6 - Big Ship Blues