Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

"Spotlight on

Lucille Bogan - Part 4"

by Max Haymes

Ms. Bogan’s ambition in “Whiskey Selling Woman” (see Part 1 in “A. B.” No.4) to “have a still on every street in this town” and no police allowed “15 miles around”, seems to have previously been realised in Birmingham, Alabama (her home town) some ten years prior to her being born. Due to the growing industries in pig iron and coal, particularly, the city attracted many farm workers off the land in Alabama and other Southern states. The population, in fact, grew so rapidly that “neither the police force nor the fire department could possibly do an adequate job. (1). This growth surpassed that of any other Southern city, in the 1880s,and Birmingham had a “Wild West” reputation with a “saloon and brothel on almost every street in the downtown area. The carrying of firearms was a common practice, because police protection could not be counted on.”(2). To be fair, this was due in part, to the small size of the force; in 1885 with a population of nearly twenty thousand “there were only 20 policemen within the city.” (3).

The

situation grew worse in the next 13 years. A picture taken in 1898 outside

Birmingham police station depicted a group of just 22 police officers. The

population in the mean time was around 38,000 in the city and at least another

20,000 in the suburbs; such as Bessemer and Pratt City. The fire department must

have been in a similar sorry state as houses often burned down because of

insufficient fire-fighting facilities. Meanwhile, “Certain curiously-named

places developed in the city like Pigeon’s Roost and Scratch Ankle, which were

so named because they were hotbeds of vice and crime.” (4). The last-named

‘hotbed’ probably alludes to the leg-irons worn by black prisoners trapped

in the horrific convict-lease system. Starting in the 1880s,”There were still

about fifteen hundred convicts in Birmingham mines...”(5) in the period

1900-1920. Alabama finally abolished convict leasing in 1928; the last state to

do so.

Lucille Bogan and lawlessness seemed to be pre-destined to be always linked. The town of Amory, Miss. where she was born (see Part 1),“was established when the railroad between Memphis and Birmingham was being surveyed.”(6). A camp was built in 1887 at a spot halfway between the two cities. “Many settlers, drawn by the railroad and the fertile soil made their homes here. There were also many transients which were of the worst element and much lawlessness and vice were common, with five saloons in operation.” (7). By the time the “better element” had asserted itself with churches, schools, etc. Bogan was Birmingham-bound. But she was headed for the city sometimes known as “Bad Birmingham, the murder capital of the world” (8) and “the dirtiest city on earth.”(9).

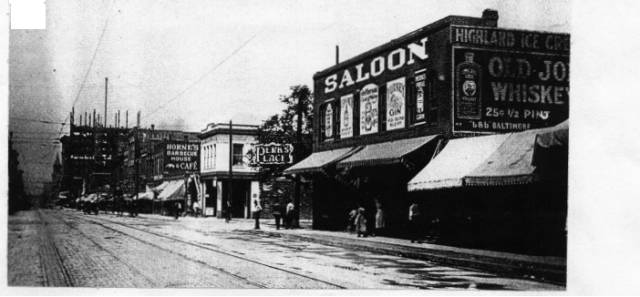

Booze

sold in downtown (city centre) Birmingham, Alabama. c.1910 on 2nd. Avenue N.

“Old Joe Whiskey” at 25 cents a ½ pint; “Turkey Gin” & “Jefferson

Club Whiskey” at 1 dollar a full quart.

Sounding

a lot like Chicago in Al Capone’s hey-day, shady businessmen and gangsters who

owned powerful liquor interests, gambling houses and brothels, had some members

of the city council on their payroll; and “seemed too powerful to control”(10).

This state of affairs was reflected in Oklahoma before statehood in 1907. The

state was then known as “The Nation”, “Indian Territory” or the “Territo’”.

As Eavenson relates, in the latter part of the 19th. century, the Territory had

“no towns and few settlements...”(11). Even if, as a generalisation, this

was not 100% accurate the few towns that certainly did exist before 1900 were

largely run by native Americans (usually half-breeds), outlaws and greedy white

land speculators. Any civic disputes

were usually settled with a gun rather than through a court. Existing outside

the control of the U.S. federal government and free from local white (and

racist) legislation, Indian Territory attracted many blacks from Mississippi,

Georgia, Alabama and other Southern states. Among them would be included

transients, criminals and prostitutes. The Nation often cropped up in the early

blues, including Ms. Bogan’s. In 1927 she recorded an “Oklahoma Man

Blues”, and included these lines:

“When

I leave here, daddy, pin crepe on this town. (x2)

An’ you know by that, me an’ my man is Oklahoma bound.” (12)

With

an obvious eye on a more lucrative market for her “wares” (bootleg booze and

prostitution) in the lawless “Nation”. Bogan’s opening lines refer to an

extension of the Southern black custom to pin black crepe over the front door

indicating a death in the house. As far as racist Alabama was concerned, she and

her man were dead because they will never be seen in that state again.

This

lawlessness is reflected in many of Lucille Bogan’s blues, already quoted. Her

attitude to life seems to have been that while she had to conform to

“establishment” rules a lot of the time, she sought and needed the

excitement of the rounder’s life with sex booze, gambling and dancing.

“A

workin’ man is my livin’ but a gambler is all I crave,

Workin’ man is my livin’, gambler is all I crave.

These gamblin’ men is gonna drive me to my grave.”

“A

workin’ man is my livin’, Lord, rounder is what I crave,

My man is gone in the war-time, an’ brought up like a slave.

Fussin’ and fightin’, are my gambler’s ways.”(13)

She

rejects the established social mores and Protestant ‘work ethic’ imposed by

the white, and therefore the black, middle-classes. Her partner is enslaved to

them and as a ‘reward’ is allowed to take part in World War I on behalf of

the U.S.A. But her “gamblin’ man” stays home and gets all the “fussin’

and fightin” he needs. Bogan not only rejects the; whites’ social controls

but their “moral standards” as well.

“What

make a woman have the blues, she knows that some tommy’s (*)

got her man;

What make a woman have the blues, when she knows that some tommy’s got her

man.

Just get you four or five good men, woman, and do the best you can.”(14)

* a l9th.c. term for a young woman.

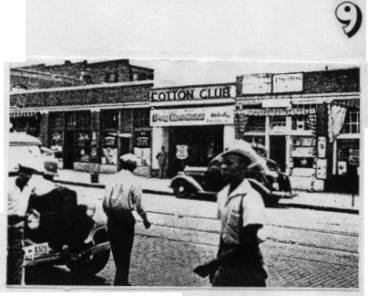

In the black section of town, in the city’s Harlem on Eighteenth St. Birmingham, Alabama 1937. It’s easy to speculate that Lucille Bogan sang her blues in the Cotton Club!

This

amoral/immoral streak runs through most of Bogan’s blues which included

references to prostitution such as “Tricks Ain’t Walking No More” and

“Stewmeat Blues”. (see Part 1). “I’m evil an’ mean as I can be”, and

“I ain’t no thin’ but a mistreater baby”, she declared on “Pig Iron

Sally” (see Part 3), swallowing her industrially-polluted environment and spitting

it right back out. Rarely, does she attempt to distance herself from this

“anti-establishment position as she does on “Reckless Woman” (Pt.3).

Together

with the theme proclaiming her strong sexuality, as in the unexpurgated “Shave

‘Em Dry (Pt.3) and her preference for “struttin’ it in the rough” on

“Strutting My Stuff” (Pt.3) you get the definite impression of a woman who

has a strong sense of ‘self’ and her own worth as a human being. As a black

feminist has noted “the assertion of individuality and the implied assertion -

as action, not mere verbal statement - of self is an important dimension of the

blues.”(15). Williams was referring to female blues but her observation is

just as true for the male singers. In the case of Lucille Bogan her

self-assertion was not so much implied - but actual.

She

did not sound, either vocally or by the contents of her blues, like someone to

be messed with. Her sense of involvement with illicit liquor and prostitution

would seem to support this. She had the same tough attitude towards men. At

least one of her relationships points to her husband/partner being a railroad

man, who worked as a fireman, probably on the M. & O. or the T.& N.0.

RR. She had at least 2 marriages or serious relationships and possibly 2 or more

affairs; one involving another blues singer, Will Ezell, and an unknown man who

lost his life in a cyclone. Although a tough and extrovert character, Lucille

had her vulnerable side, as shown in “Black Angel Blues” (Pt.3), when she

fell deeply in love.

References

1.

"Yesterday’s Birmingham”. Malcolm C. McMillan. Seeman Publishing, Inc.

Miami, Fla. 1975. p.37.

2.

Ibid.

p.38.

3.

Ibid.

4.

Ibid.

5.

Ibid.

p.76.

6.

"Hometown

Mississippi”. James F. Briegar. Historical & Genealogical Association of

Mississippi. 1980. p.338.

7. lbid.

8. McMillan.

Ibid. p.75.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. "The

First Century And A Quarter Of American Coal Industry”. Howard N. Eavenson.

Privately printed. Koppers Building. Pittsburg, Pa. 1942. p.343.

12. "Oklahoma Man Blues”. Lucille Bogan vo.; prob. Will Ezell pno. c.-/7/27. Chicago, Ill.

13. "Wartime

Man Blues”. Lucille Bogan vo., speech; Papa Charlie Jackson bjo. c. —/6/27.

Chicago Ill.

14.

”Wcmen Won’t Need No Men”. Lucille Bogan vo., speech; Will Ezell pno. c.—/6/27. Chicago Ill.

15.

" Black Feminist Thought” .

(Quote from Sherley Anne Williams.) Patricia Hill

Collins. Unwin Hyman. London. 1990. p.104.

Copyright © 2001 Max Haymes.

All rights reserved.