Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Got The Blues For Chattanooga*

(including a survey of Lookout Mountain, the Tennessee

River & Muscle Shoals)

by 'Mississippi' Max Haymes

*= Chattanooga Blues Ida Cox 1923

I

“Goin’ Up On Lookout Mountain”

This article was inspired by a poetic and far-sighted verse recorded by a blind blues singer in the late 1920s! Twelve-string maestro, Blind Willie McTell recorded his beautiful “Drive Away Blues” for Victor Records in 1929.

“Goin’ up on Lookout Mountain, an’ look down to Niagara Falls,

Niagara Falls;

Sweet mama, Niagara Falls.

Goin’ up on the Lookout Mountain, look down to Niagara Falls,

Niagara Falls;

Seem like to me I can hear my Atlanta mama call;

I could hear her call.” (1)

Around

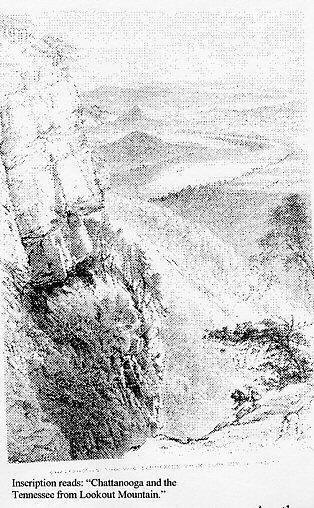

half-a-century earlier two white men travelled over much of the U.S. in an

attempt to write and sketch natural/picturesque beauty spots before they

succumbed to industrial progress. One area covered was Lookout Mountain

standing some 1,500 feet above sea-level. O. B. Bunce - the writer of the team -

observed that “On the summit of Lookout Mountain the northwest corner of Georgia

and the northeast extremity of Alabama meet on the southern boundary of

Tennessee.” He adds: “It is the summit overhanging the plain of Chattanooga

that is usually connected in the popular imagination with the title of Lookout,

but the mountain really extends for fifty miles in a south-westerly direction

into Alabama.” (2).

Around

half-a-century earlier two white men travelled over much of the U.S. in an

attempt to write and sketch natural/picturesque beauty spots before they

succumbed to industrial progress. One area covered was Lookout Mountain

standing some 1,500 feet above sea-level. O. B. Bunce - the writer of the team -

observed that “On the summit of Lookout Mountain the northwest corner of Georgia

and the northeast extremity of Alabama meet on the southern boundary of

Tennessee.” He adds: “It is the summit overhanging the plain of Chattanooga

that is usually connected in the popular imagination with the title of Lookout,

but the mountain really extends for fifty miles in a south-westerly direction

into Alabama.” (2).

Another descriptive observation by Bunce can be seen as the precursor of McTell’s encapsulated poetry. From the top of Lookout Mountain “Your vision extends, you are told, to the great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, which lie nearly a hundred miles distant…Your eye covers the entire width of Tennessee; it reaches, so it is said, even to Virginia, and embraces within its scope territory of seven States. These are Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Virginia, Kentucky, North and South Carolina.” (3). Blind Willie McTell’s imagination is even more vivid as Niagara Falls, on the U.S./Canada border, is over 1,000 miles away – as the crow flies! (Appendix ‘A’)

Another source of inspiration for Blind

Willie appears much closer to his own era in the shape of a 1923 recording by

Ida Cox. One of the top 4 vaudeville-blues singers, along with Ma Rainey,

Bessie and Clara Smith (no relation), Ms. Cox also includes a neat précis of

Bunce’s words from the 19th. century. Whilst transforming the

mountain into a personal look-out for her wayward man!

Another source of inspiration for Blind

Willie appears much closer to his own era in the shape of a 1923 recording by

Ida Cox. One of the top 4 vaudeville-blues singers, along with Ma Rainey,

Bessie and Clara Smith (no relation), Ms. Cox also includes a neat précis of

Bunce’s words from the 19th. century. Whilst transforming the

mountain into a personal look-out for her wayward man!

“Goin’ up on Lookout Mountain, lookin’ far as I can see;

Tryin’ to find the man that made a monkey out of me.

Reached the depot in time to catch the cannonball;

Got the blues for Chattanooga, won’t be back ‘til late next fall.”“Down in Chickamauga, float on the falls;

Grandest bunch of soldiers that you ever saw.

On the Tennessee River, down to the lock an’ dam;

Searchin’ every mud hole tryin’ to find my good man Sam.” (4)

Chickamauga is a Georgia town situated some 30 miles south of Chattanooga. Like many names in the U.S. this is a Native American word which translates as ‘river of death’ as with the Yazoo River in neighbouring Mississippi. Also the site of one of the last Civil War victories for the Confederates, in September, 1863, which the Union forces avenged in November at the Battle of Lookout Mountain/Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge. Although the recently freed slaves might recall Lookout Mountain with some fondness because of this Union victory, in a general way; some individuals remembered a more personalised downside. One freedman, J. W. Lindsay, had been enslaved in Tennessee and was interviewed in 1863 while living in Canada. He recollected that while “some few slaveholders…thinks a good deal of their children by their slaves” (5), on the subject of racial interbreeding, there were cases when “white mistresses will surmise that there is an intimacy between a slave woman and the master, and perhaps she will make a great fuss and have her whipped, and perhaps there will be no peace until she is sold. I have seen slaveholders with little bits of children not more than three or four years old. They want a little money and take a baby off and get one or two hundred dollars for him.” (6). But the old slave was just as vulnerable as the very young. “I remember once, on crossing Look Out Mountain (sic), in Tenn., with a drove of hogs. I saw two old black people there, in the neighbourhood of eighty years old. They could not be of any service, so their master had turned them loose upon the mercy of the world. That is very often the case. These two old persons were pretty near starved. When we went into the room where they were, we didn’t see anything but dirt, poverty and distress.” (7).

The seemingly odd phrase that completes the opening line of Ms. Cox’s second verse ‘float on the falls’ is one that I’m not entirely happy with! However, if that is indeed what she does sing then this could be a reference to a car float on the Tennessee River, then still in operation. [Car floats were adapted barges/steamboats equipped with rails to transfer trains across larger rivers or streams instead of building a far more expensive bridge. See “Railroadin’ Some” (Max Haymes. Music Mentor Books. - publishing in progress - due end 2005) for in-depth details of car floats, floating bridges and Sleepy John Estes]. This refers to railroad freight and passenger cars rather than automobiles. The phrase could be clarified (or not!) if the alternate takes of “Chattanooga Blues” were to be discovered.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

II

“On the Tennessee River”

The references by Ida Cox to a railroad (a ‘cannonball’ is a fast train) and the Tennessee River point up the two most important factors in a new town or city surviving in the mainly rural South at the turn of the 20th. c. Without these avenues of trade and commerce, a budding urban centre would wither and die. As John White noted: “Bulk commodities (in the U.S.) have traditionally moved by rail and barge,” (8). Indeed, as with the Tennessee River, these two modes of transportation were intertwined. Even when steamboats still held sway in the later 19th.c., they were carrying loads which helped create and maintain the railroads and this included the trains themselves; which were to largely replace them. More on this a little later on.

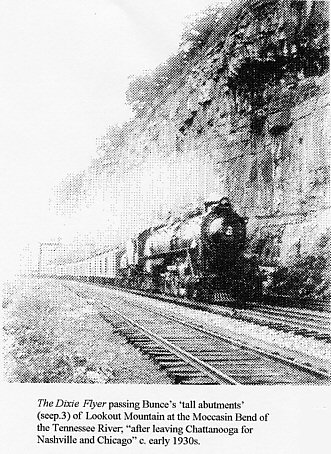

Another evocative passage by Bunce describes the Tennessee River as from an age long gone and yet was less than 150 years ago. “The Tennessee comes sweeping down upon Lookout Mountain as if it is confidently expected to break through the rocky barrier and reach the Gulf by an easy course through the pleasant lowlands of Alabama. The flood reaches the base of Lookout’s tall abutments, and finding them impenetrable, sweeps abruptly to the right, breaking through the barrier of hills that lie in its course, and, as if with a new purpose at heart, abandons its hope of the Gulf, to eventually reach it, however, after a double marriage with the Ohio and the Mississippi.” (9). The ‘Gulf’ of course, being the Gulf of Mexico. Bunce adds: “The Tennessee is formed by the union of the Clinch and the Holston Rivers at Kingston, and together with its principle affluent, attaining a length of eleven hundred miles.” (10). Kingston, Tenn. being situated some 70 miles north-east of Chattanooga.

Apart from trade to Kingston, Chattanooga was a steamboat centre emanating to other major cities such as Knoxville within the State; Paducah, Ky.; St. Louis, Mo.; Atlanta, Ga.; New Orleans, La.; and Cincinnati, Oh. All this steamboat activity provided many black Southerners with employment. As Frederick Way states in his essential book on steam towboats “most (blacks) were roustabouts, waiters, cooks, or stewards on packets and deckhands or firemen on some towboats.” (11) if they worked on the river. [Generally speaking, steamboats fell into two categories. The towboat hauled freight and occasionally passengers while the packet was primarily a passenger boat that sometimes took on industrial goods. For practical reasons (on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, at least) towboats shoved their cargo from astern; be it coal barges, a showboat, etc.] On some occasions, more rarely, a black citizen might make it to the position of Captain. One such, in the first 2 decades of the 20th. c., was Captain Cumberland W. Posey of Pittsburgh, Pa. As well as owning/building several steamboats he was “part owner of the Diamond Coal & Coke Co.” (12) in his hometown. Famous blues singer, Bessie Smith even adopted the persona of a steamboat captain in her “Florida Bound Blues” as she indicates to the Red Cap porter, also black, at a train station, to take her luggage. [For more on Red Cap porters in the early Blues, see “Railroadin’ Some”. Ibid.]

“Hey! Hey! Red Cap help me with this load;

Red Cap porter, help me with this load.

Spoken: “Step aside!”

Oh! As steamboat Mister Captain, let me get on board.” (13)

As Ms. Smith was from Chattanooga she was no doubt familiar with the steamboat trade on the Tennessee River. [As a pure matter of interest there was a packet boat called the Bessie Smith! Built in Alabama “and completed at Florence, Ala., 1897” (14), some 3 years after Bessie Smith’s birth date. Albeit the packet only ran on the Upper Ohio River.] She obviously still identified with the city as illustrated in an earlier song where she is boasting of sexual prowess – a not unusual stance for a blues singer!

“I got a man in Atlanta, two in Alabama, three in Chattanooga;

Four in Cincinnati, five in Mississippi, six in Memphis, Tennessee;

If you don’t like my peaches, please let my orchard be.” (15)

Jim Jackson, a veteran of the medicine show, was born (1884) in Hernando, Miss. but soon re-located to Memphis across the State line. Along with Frank Stokes as one of the most popular performers down on ‘Fourth an’ Beale’, he recorded “My Monday Blues” (Vo unissued) featuring Bessie Smith’s Chattanooga “climatic chorus in which (she) sings a repeated musical figure five times, with a release to great effect.” (16) Actually, a vocal form of stop-time passages favoured by some guitarists and banjoists including Blind Blake and Papa Charlie Jackson, respectively.

“I’m got a gal in Georgia, one in Louisiana,

Four in Chattanoogie, six in Alabama;

Four or five women right down in Memphis, Tennessee.

If you don’t like my peaches, let my orchard be.” (17)

But Bessie had seemingly borrowed this ‘climatic’ verse from a source dating back to the turn of the 20th. century. In 1900 a popular Irish comic, Pat Rooney, wrote one of many ragtime ‘coon-songs’ that were all the rage then; called “I’ve Got a Gal for Ev’ry Day in the Week” (18). Although Oliver says that Rooney’s song was the origin of versions in the blues, as featured by Jim Jackson for example, I feel this was drawing on an earlier popular theme extant in black music during the close of the 19th. century; which Rooney eventually picked up on via oral transmission.

In the first place Jim Jackson is well-known by blues collectors for his large recorded repertoire of traditional songs from the pre-blues era. Secondly, he recorded his ‘every day in the week’ song on four occasions with three being issued at the time; twice for Vocalion as “My Monday Blues” and twice for Victor as “My Monday Woman Blues”. Both titles varied in their floating or traditional verses except for the Chattanooga one quoted above, which appeared in all four versions he cut for these sessions. Thirdly, Jim Jackson was in his mid-teens before Rooney wrote his own lyrics (in generally less colourful phrasing) and was old enough to be singing a 19th. century precursor of his “My Monday Blues”. Finally, it is significant that Rooney’s third line quoted by Oliver runs:

“I’ve got a Sunday girl and she’s a jet-black pearl” (19)

Indicating a definite source from African American roots.

Actually, Bessie Smith’s “Mama’s Got The Blues” only connection with this popular blues theme is the ‘climactic’ verse. A similar construct is present in a song by Texas pianist Bert M. Mays who commenced recording at the tail-end of 1927. Mays inserts into his original and very moving blues a re-located version of the Chattanooga stanza, although he still includes Tennessee.

“I got a gal in Alabama, I got one in Louisiana;

I got one in Texarkana, I got one in Corsicana;

Got one in Indiana, nineteen in Tennessee.

I wants another half-a-dozen, just to run around with me.” (20)

The last line being an adaptation from another Texas singer, Sippie Wallace and her “Up The Country Blues” from 1923. Mays also uses a form of a complete verse from Sippie’s song, also in stop-time fashion, and later employed superbly by Blind Willie McTell on his “Statesboro Blues”. [Wallace’s “A Man For Every Day In The Week” in 1926 does not include the Chattanooga stanza. For more on the relationship between her “Up The Country” and McTell’s “Statesboro”, see “Railroadin’ Some”; ibid]. Since another version of “Mama’s Got The Blues” by Lillian Harris made around the same time as Bessie’s, omits the Chattanooga verse in both her issued takes, I presume she was from elsewhere – New Orleans? Harris is not featured in either “Blues Who’s Who” or indeed any similar books on jazz artists. As her other versions of Bessie Smith recordings were made as ‘covers’ it is safe to assume that is also the case with “Mama’s Got The Blues” – despite the “c. late April” legend in B. & G.R. (21). Lillian Harris acquits herself well, even if she is no Bessie, and the white New Orleans-style band lend a jolly atmosphere complete with a clip-clopping drummer! The Chattanooga verse is also absent from the original version of “Mama’s Got The Blues” by Sara Martin in mid-December, 1922, with a youthful Fats Waller on piano. Composed by Sara and another pianist, Clarence Williams, this makes up the only three recordings of the song listed in B. & G.R., and while a superior singer to Lillian Harris; she has to give the nod to Bessie – like most other female vaudeville blues singers. Significantly, Sara was “raised in Louisville, KY;” where she was born “June 18, 1884” (22), rather than in Tennessee. Only two other sides in pre-war blues feature Chattanooga in their title: “Chattanooga Blues” by Mary H. Bradford in September, 1923, a different song about going to her man in that city, and another version by Lucille Hegamin recorded a month later as “Chattanooga Man”.

Sara Martin, Bessie

Smith, Mary Bradford, Lucille Hegamin, and Lillian Harris sit under the rather

wide umbrella of ‘vaudeville-blues’ (nee classic blues) which is essentially an

early urban form of the genre. One of the roots of this urbanisation is the

minstrelsy stage dating back to before the Civil War (1861-1865). While Bessie

was born in Chattanooga “on the 15th. April 1894… the date given here

is that which she gave on her application for a marriage license” (23), a

fairly obscure singer, ‘Hound Head Henry’, sounds a little older. Certainly, he draws on minstrelsy as well as the vaudeville stage. Another

almost complete mystery figure like Lillian Harris, Henry recorded 8 sides between 1st.

August and 18th.October in1928 for Vocalion. Then vanishes from the

scene, which sadly is a quite familiar scenario in the early blues. He might be

from Alabama which is home state for his only accompanist, Cow Cow Davenport.

Also the duo included a part-version of the ‘climatic’ verse with an Alabama

reference in standard 3-line format:

Sara Martin, Bessie

Smith, Mary Bradford, Lucille Hegamin, and Lillian Harris sit under the rather

wide umbrella of ‘vaudeville-blues’ (nee classic blues) which is essentially an

early urban form of the genre. One of the roots of this urbanisation is the

minstrelsy stage dating back to before the Civil War (1861-1865). While Bessie

was born in Chattanooga “on the 15th. April 1894… the date given here

is that which she gave on her application for a marriage license” (23), a

fairly obscure singer, ‘Hound Head Henry’, sounds a little older. Certainly, he draws on minstrelsy as well as the vaudeville stage. Another

almost complete mystery figure like Lillian Harris, Henry recorded 8 sides between 1st.

August and 18th.October in1928 for Vocalion. Then vanishes from the

scene, which sadly is a quite familiar scenario in the early blues. He might be

from Alabama which is home state for his only accompanist, Cow Cow Davenport.

Also the duo included a part-version of the ‘climatic’ verse with an Alabama

reference in standard 3-line format:

“I got a gal in Alabama, gal in Tennessee;

Got a gal in Alabama, gal in Tennessee.

But that gal want that dollar, that’s the sweet babe for me.” (24)

Davenport might have met him in the late 19-teens “through early 20s” when he worked in Haegs Circus “as black-face singing/dancing minstrel” (25), when the circus was in Macon, Georgia, some 160 miles south-west of Chattanooga. But this is pure speculation on my part. What we do know is he included unique references, in the Blues, of travelling to the North as a roustabout on a steamboat to Chicago, and rendering a credible imitation of the boat’s lonesome whistle to boot.

Spoken: “Ha-ha-ha! Hello there, Cow Cow. Me an’ a few can sail the cotton bales loaded here,

boys. This here boat is goin’ up North, son. We ain’t gonna be here long. Ha! Come on,

man. Please take ‘im out, now, son. All aboard! Whooooo! Whooooo! Whooooo!”Vocal: “There’s a boat goin’ up North an’ we’ve bin longin’ to go;

There’s a boat goin’ up North-ooooh! An’ we’ve bin longin’ to go.Spoken: “Play it, Professor!”

When I get up there, I ain’t comin’ back no more.” (26).

Having steamed out of Alabama up the Tennessee River, joining the Ohio at Paducah, Ky., which in turn merges into the Mississippi at Cairo, Ill., Henry & co. would have made their way northward past St. Louis and onto Grafton, Ill. There they veered right to the Illinois River taking them finally to the Des Plaines River and their destination. On spying the landing at last in Chicago, Hound Head Henry has the boat blow again, before mooring and unloading the cotton bales along with the rest of the ‘few’ crewmen; and then dropping his head commences to singing an’ crying.

“I’m in Chicago where I’ve bin longin’ to be;

Ohh-yaw-ooooooh! Where I’ve bin longin’ to be.

An’ I know my good gal waitin’ right there for me-eeee” (27)

Included in the only writing I have come across on Hound Head Henry in nearly 40 years, is the comment from Alexis Korner (c.1960): “Hound Head Henry, accompanied by Cow Cow Davenport, barks and brays most convincingly…and, incidentally, proves that he also possesses a good singing voice. It is pitched approximately in the tenor range,” (28). Of Henry’s personal life, Korner states “there is virtually nothing known. Even Paul Oliver,…could find nothing in his files about this entertaining singer.” (29).

Whether Hound Head Henry ever made such a trip (well over 1,500 miles-[Compare with the 1,000- mile distance from Lookout Mountain, as the crow flies (p.1). One of the major problems with river travel as opposed to rail or highway was that the meandering streams added excessive mileage to the journey. Former steamboat captain Frederick Way Jr. gives a graphic example. “Poplar Bluff, MO is 78 highway miles west of Cairo ILL but by river the trip would require…a total of 858 miles” (30). Having travelled on three waterways: the Mississippi, White and Black Rivers to complete the journey]. we’ll probably never know. If he did he might have taken work on the R.C. GUNTER, a stern-wheeler packet built in “Chattanooga, Tenn., 1886…by Chattanooga & Decatur Packet Co”. Presumably on the Tennessee River in her early days before she “Later went to the Illinois River,” (31). Decatur, Ala. is on the Tennessee. As well as building steamboats, Chattanooga had no less than 5 (built elsewhere) named after her. Both the 4th. and 5th. worked on the lower Tennessee. The latter is of interest as one of the only references I’ve come across, as a ‘gospel boat’. This was a stern-wheeler called MEGIDDO before being re-named CHATTANOOGA. The 4th. boat so-named was a stern-wheeler packet built in 1878 and also “Ran below Chattanooga on the Tennessee.” (32).

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

III

“Muscle Shoals Blues”

As I write (mid-May, 2005) the news came over the air on B.B.C. Radio 4’s “Today” programme that the recording studios at Muscle Shoals in Alabama have closed and will be re-located further up the Tennessee River. These studios have represented a strong icon for fans of funky soul music and r ‘n b for some thirty years. Artists such as Booker T. & The M.G.s, Steve Cropper, etc. are big names in the studio’s recording history. Even in the 19-teens there appears to have been a thriving music scene in the area; at least for budding blues players. A youthful Ed Bell, from Fort Deposit, Ala., was judged to have “no musical aptitude” by contemporaries until an older man took him to Muscle Shoals. This was one Joe Pat Dean, a cousin of Bell’s, according to a friend of the latter when interviewed much later. Dean was “A gittar-pikker and a dancer. A slick nigger. A man killed him.” (33). This was one George Poole who played with Ed Bell and he observed that after Dean took Bell to Muscle Shoals in 1919 “…when he came back he could play. Got so good, Joe Pat wouldn’t play with him any more.” (34) However, back in the 19th.c. and the beginnings of the 20th. Muscle Shoals was often viewed with fear, frustration, or a source of employment; depending on where you stood in the scheme of things in the South at the time. The name for this river hazard in Cherokee is “dagunahi ‘mussel place’, from daguna ‘mussel’ and –hi ‘place’…In 1892 the U.S. Board of Geographic Names chose ‘muscle’, an obsolete form of ‘mussel’, as the official spelling of the word.” (35).

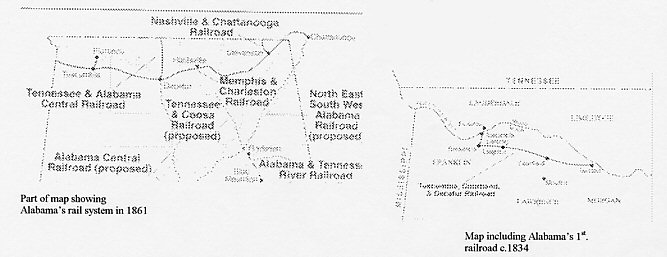

|

Part of map showing Alabama’s rail system in

1861 |

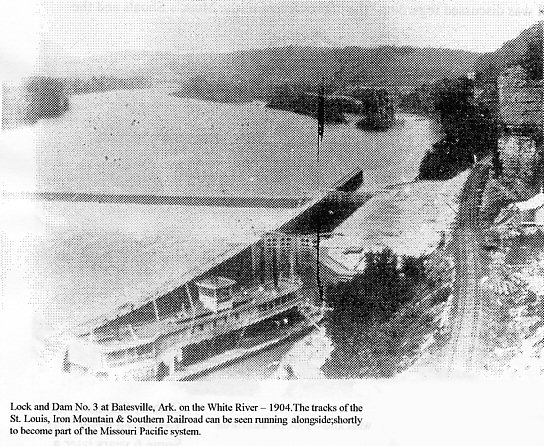

The already-mentioned gospel boat re-named CHATTANOOGA had run on the Upper Tennessee up to the end of 1920, but by January, 1921, she was part of the “Chattanooga-Decatur” traffic. There was also one packet boat named in the ‘City series’ of which there were many across the U.S. The CITY OF CHATTANOOGA was a stern-wheeler which operated from Chattanooga to St. Louis, Mo. Way states: “There were many delays and troubles in the vicinity of Muscle Shoals.” (36). This represented an almost impenetrable barrier for river trade from the lower part of the Tennessee River in Chattanooga and Decatur for instance, and places on the upper river such as Florence, Ala. and other destinations further north. One of these was the very important trading centre of St. Louis, visited by the CITY OF CHATTANOOGA. Let O.B. Bunce put it from a point of view in the late 19th. c. “Steamers navigate different portions, (of the river) but a succession of shallows and rapids in Alabama known as “Muscle Shoals”, bar vessels from its lower waters to the upper; and below Chattanooga exist serious obstacles to steamboat navigation, known as the “Suck” and the “Pot” (37). Nevertheless, determined companies took up the challenge in their quest for trade – and profit. Not all were successful as Way reports of the fate of a packet, the MARY BYRD ,which was built in 1866 and “Operated on the Tennessee River…Sank in the “Suck” below Chattanooga in 1870.” (38). This would have hardly been a unique event and all steamboats, packet or towboat, had to run the gauntlet if they were to stay in business. This of course would have included the boat Hound Head Henry purports to have travelled on, heading up to Chicago, on his “Steamboat Blues”.

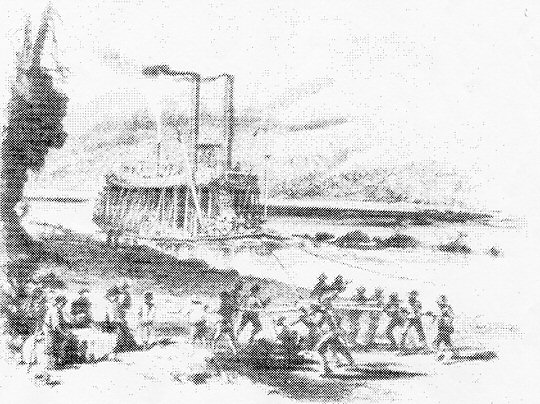

As with the former MEGIDDO gospel boat, the “Suck” would take part in the on-going oral transmission process of both blues and gospel songs. Basically, because most of the arduous physical work on the Southern rivers was performed by blacks. Also because these jobs would be labour-intensive and therefore often accompanied by some form of work song; as has been noted by American and European travellers during the 19th.c. in their numerous writings. While Bunce only briefly describes the “Pot”, around 20 miles below Chattanooga, as a maelstrom which is quite capable of shifting “vast trees…in its fierce turmoil and swept out of sight” (39); he delivers a graphic scenario of the ”Suck”. He details how the boats were navigated or ‘warped’ through, before the coming of railroads using black labour (probably slaves – see illustration below).

The “Suck” is thirteen miles from Chattanooga and therefore the first great hazard steamboat crews would face. “This phenomenon is caused by a fierce little mountain current, called “Suck Creek”, which, in times of high water, brings from its rocky fastnesses [In this context a ‘fastness’ refers to an embankment, “abutment, shore, etc.” (40)]. such masses of debris that the river bed is strewed with bowlders, (sic) and a bar formed, which compresses the channel into a narrow, swift, and dangerous current. Thirty years ago (c. late 1840s-M.H.) the Government erected a wall some forty feet distant from the left bank, and, through the narrow passage thus formed, boats ascending the river are warped up by means of a windlass on the shore.” (41). At the time of his writing (c.1874) Bunce states that the government (presumably the state) “is now endeavouring to remove the obstructions and widen the channel, which at this point is narrowed from the average of six hundred feet to two hundred and fifty; and hence the novel and picturesque sight of a steamer struggling up against an adverse current by means of a windlass on the bank, with the songs and shouts of the labouring deck-hands, will soon be, even if it is not now, a thing of the past.” (42).

There was an alternative, for steamboats of the right size; the Muscle Shoals canal in Alabama. The idea of cutting a diversionary channel or canal by a river, with wooden locks and dams, goes back to at least the turn of the 19th.c. But it was 1828 before a project was discussed regarding “the improvement of the Muscle Shoals and the Colbert Shoals in the Tennessee River.” (43). Some 6 years later a canal was constructed but left un-improved “a length of the river both above and below the canal. This unimproved section was difficult, dangerous and very often impracticable of navigation, and therefore the canal was not used for commercial purposes and soon fell into decay.” (44) [However, a more precise account is given by steamboat historian James Lloyd much nearer the event, in 1856. “Steamboats of the first class ascend this river (i.e. the Tennessee –M.H.) as far as Florence, Alabama, which is situated on the north bank at the foot of the rapids called Muscle shoals, (sic) which are between Lauderdale and Laurence counties, Alabama…In 1840, a canal twelve miles long was built around the shoals, but unfortunately the locks were made too short to admit even the smallest steamboats that navigate that river; it was soon abandoned, and the channel has been filling up for the last fifteen years.” (45)]. It was to be nearly 40 years, in 1873, before Muscle Shoals was seriously considered by Alabama’s state legislature again. Although ‘provisions’ were made to re-build and enlarge the canal, due to the usual drawn-out political debates it was 1877 before work started. “In 1890 the canal was completed, at a total cost of $3,191,726.50 and since then the maintenance of the canal has cost an average of $600,000 per year. This is the canal now (1921) in operation in the Muscle Shoals district.” (46).

This was in the middle of this district

and known as “Big Muscle Shoals” being some 14 miles long compared to the total of

the whole of this river hazard which was 36 miles. Lower down the river was the

“Little Muscle Shoals” which was still untamed. Several meetings of a board of U.S. Army

engineers took place from 1889 to 1916 to improve this

section, without any results. However, out of necessity (?) when W.W.I was

enjoined by the U.S.A. “Two nitrate plants were constructed for Sheffield and

Tuscumbia in 1917…” (47).

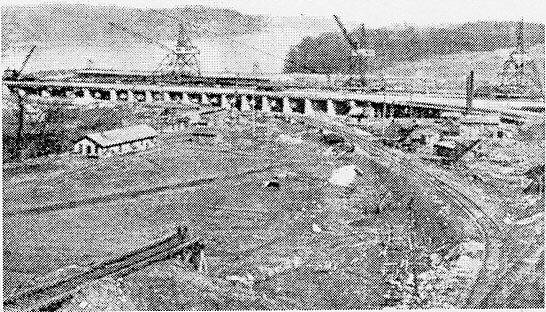

This would account for Ida Cox singing about the “grandest bunch of soldiers

that you ever saw.” on her “Chattanooga Blues”.

The soldiers of the United

States Corps of Engineers (USE) would still be there at Muscle Shoals for

another 8 years. The first of the nitrate plants was inoperable (Dam No.1 at

Sheffield, Ala.) due to faulty installations but No.2 opened at Tuscumbia, Ala.

in 1918. U.S. president Woodrow Wilson “issued a letter to the secretary of war

authorising the construction of dam and power house No.2 at Little Muscle Shoals

for the purpose of furnishing power to the nitrate plant…Dam No.2, better known

as “Wilson Dam”, was to be constructed in cooperation with the Muscle Shoals

hydro- electric

power company.” (sic) (48).

The soldiers of the United

States Corps of Engineers (USE) would still be there at Muscle Shoals for

another 8 years. The first of the nitrate plants was inoperable (Dam No.1 at

Sheffield, Ala.) due to faulty installations but No.2 opened at Tuscumbia, Ala.

in 1918. U.S. president Woodrow Wilson “issued a letter to the secretary of war

authorising the construction of dam and power house No.2 at Little Muscle Shoals

for the purpose of furnishing power to the nitrate plant…Dam No.2, better known

as “Wilson Dam”, was to be constructed in cooperation with the Muscle Shoals

hydro- electric

power company.” (sic) (48).

There were also plans to build another canal and a Dam No.3. But the Alabama

congress baulked at the $10,000,000 requested by the bill before the Senate in

February, 1921. Eventually, a series of improved locks and dams were include in

the project and it was to be 1926 before the Wilson Dam finally opened – nearly

100 years since improvements at Muscle Shoals were initially

proposed. Although Woodrow Wilson did

not live to see this event – as he died in

1924, before

Dam No.2 was completed.

There were also plans to build another canal and a Dam No.3. But the Alabama

congress baulked at the $10,000,000 requested by the bill before the Senate in

February, 1921. Eventually, a series of improved locks and dams were include in

the project and it was to be 1926 before the Wilson Dam finally opened – nearly

100 years since improvements at Muscle Shoals were initially

proposed. Although Woodrow Wilson did

not live to see this event – as he died in

1924, before

Dam No.2 was completed.

It was in 1926, that the only blues recording with Wilson Dam in the title was released. Born in Birmingham, Ala. in 1893, singer Leola B. Wilson was a fine blues artist who travelled the South in tent shows with her first husband Isiah I.Grant, “born in 1886 in St. Petersburg, FL, and…a ‘baritone singer’;” (49). Leola’s maiden name was Pettigrew and used her initial spouse’s identity for her stage name, coupled with a childhood tag and became ‘Coot Grant’. When her husband died in 1920 she teamed up with a Jacksonville, Fla. pianist who she subsequently married. Wesley Wilson and Leola went out as Coot Grant & Kid/ ‘Socks’ Wilson. A team in the famous Butterbeans and Susie mould which would last for 50 years not only as singers but “dancers, actors, and comedians…” (50). But at this particular session Coot was teamed with the superb swinging sounds of Blind Blake – the giant of East Coast ragtime guitar. She sings of Wilson Dam as an opportunity to make some easy money from the workers on the dam, using her man’s prowess at shooting craps; a very popular black dice game in which 7-11 was a winning combination.

“ ‘Sound seven-eleven’, I hear my daddy cry. (x 2)

‘I need some money to buy some shoes for that baby o’ mine’.”“Way down South where I wanna be. (x 2)

There is Saturday night payroll always waitin’ for me.” (51)

To get ‘way down South’ Ms. Wilson plans to ride the former Memphis & Charleston RR. which had become a part of the Southern in 1899.

“Train blowin’ from Memphis, gon’ stop at Birmingham. (x 2)

Keep goin’ straight through, down to Wilson’s Dam.” (52)

An even more rural

sound is to be heard from one of the finest of all women blues singers, Lucille

Bogan. Although born in Amory, Miss. she soon moved to Birmingham, Ala. or

quite likely to Fairfield, one of the Magic City’s sprawling suburbs.

[See Ch.2 in “Railroadin’ Some”. Ibid. For more on Lucille Bogan, Fairfield and

the M. & O.. RR]. Like Coot Grant she was married twice (at least!) and

recorded from 1923 to 1935. On meeting the superb blues pianist Walter Roland

c.1933 they formed one of the most awesome and very moving musical partnerships

in the world of the Blues. Ms. Bogan also wants her man to earn money for her,

but she has her eye on getting him working for the USE “where they don’t work

men so hard” and the jobs were less dangerous than some of the more usual ones

‘reserved’ for blacks in the early 20th. century; such as logging in

the forests or “piney woods”

An even more rural

sound is to be heard from one of the finest of all women blues singers, Lucille

Bogan. Although born in Amory, Miss. she soon moved to Birmingham, Ala. or

quite likely to Fairfield, one of the Magic City’s sprawling suburbs.

[See Ch.2 in “Railroadin’ Some”. Ibid. For more on Lucille Bogan, Fairfield and

the M. & O.. RR]. Like Coot Grant she was married twice (at least!) and

recorded from 1923 to 1935. On meeting the superb blues pianist Walter Roland

c.1933 they formed one of the most awesome and very moving musical partnerships

in the world of the Blues. Ms. Bogan also wants her man to earn money for her,

but she has her eye on getting him working for the USE “where they don’t work

men so hard” and the jobs were less dangerous than some of the more usual ones

‘reserved’ for blacks in the early 20th. century; such as logging in

the forests or “piney woods”

“I’m goin’ to Muscle Shoals to get my man a government job;

Say, I’m goin’ to Muscle Shoals, get my man a government job.

He wants to work on the lock an’ dam, where they don’t work men so hard.”“They get men for the forest, and they workin’ along the Wilson Dam;

They get men for the forest, workin’ along the Wilson Dam.

Down in Muscle Shoals, Lord, 80 miles from Birmingham.”“Put your arms around me, daddy, like a ring around the risin’ sun;

Put your arms around me, daddy, just like a ring around the risin’ sun.

If you make any money in Muscle Shoals, daddy, won’t you give me some?”“On the Tennessee River was where they built the Wilson Dam;

On the Tennessee River, where they built the Wilson Dam.

Well, miles from harm an’ 80 miles from Birmingham.” (53)

The train again makes its appearance as a way of getting to Muscle Shoals, but unlike Coot Grant, Lucille intends to make sure her man gets on!

“He got his suitcase packed, an’ his trunk has all gone on;

He’s got his suitcase packed, an’ his trunk is all gone on.

Standin’ here with me, Lord, waitin’ on that train to run.” (54)

Another singer, Bertha Ross, sounds so remarkably like Lucille Bogan on her 1927 recordings, she may well be her! As well as recording her only session in Birmingham, Ms. Ross was accompanied by an Alabama ‘group’ called the Bessemer Blues Pickers which included Jaybird Coleman, Alabama’s most archaic harp-blower and vocalist. Down on Muscle Shoals apart from shooting craps or working ‘legit’ for USE, some women found a lucrative trade among the workers as prostitutes.

“Now, I’m goin’

to the river, Lord, gon’ work it up an’ down;

Ain't nothin’

on the lock an’ dam, women, I can’t get in town.” (55)

But despite the various above occupations offered by the construction of the Wilson Dam, soon after the end of W.W.I in 1918, the “nitrogen and fertilizer plant at Muscle Shoals…had become obsolete and was lying idle.” (56). This was largely due to political ‘dithering’ as has already been referred to. Although a proposal for a multi-purpose river basin scheme had been put before various government bodies through the 1920s, it was always knocked back. On two occasions by U.S. Presidents Coolidge and Hoover using their veto to block the bill. It was not until the election of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 that this scenario was turned around. Drawing on the ground-laying work of the far-sighted Senator for Nebraska, George Norris, and other leading figures, the Tennessee Valley Authority came into being. “Roosevelt endorsed the Norris proposal for multipurpose development, declaring that conditions in the Tennessee Valley offered an opportunity to set an example of planning for the whole country. Roosevelt’s election to the presidency resulted in the launching of an experiment in river basin planning as embodied in the Tennessee Valley Authority signed on 18 May 1933.” (57). Lucille Bogan doesn’t appear to have wasted much time getting her man down to Muscle Shoals when she recorded her blues on 20th. July – some 2 months later! Such is the general topicality of the Blues.

Also topical was the first blues record made about Muscle Shoals, near the start of 1922. Recorded by New Orleans-born Lizzie Miles who appeared to be inspired by the circulating news item at the time that auto magnate Henry Ford (of Model ‘T’ fame) was offering to “take over the old nitrogen plant after World War I,” (58). Or in writer Lynn Abbott’s much later words “to buy Muscle Shoals” (59). Ms. Abbott notes that the song by Lizzie Miles was written by pioneer barrelhouse/boogie pianist George Thomas [The song by Lucille Bogan has different lyrics, tune, and vocal approach – hence “New” in her title] from East Texas and quotes a snippet from the leading black militant newspaper the Chicago Defender at the time. “Mr. Thomas has sent copies of the song to Mr. Ford and has been in communication with him with a view to having the song used to boost the Muscle Shoals proposition.” (60). Henry Ford’s plans “touched off a migration which the New York Times compared to the gold rush of ’49.” (61). That is 1849, of course. Or as Gunther put it some 30 years later: “a real estate development began; property was sold at crazy prices…(and then)…the crash came, and paved sidewalks and lampposts (sic) still stretch into a deserted wilderness (in 1947)… Muscle Shoals is probably the only point in the world where you can shoot quail and other game from concrete pavements”. (62). Lizzie Miles with her rich vocals reflects this scene in typical blues-speak on what was her recording debut.

“Hurry papa, we must leave this town;

Got the blues for Muscle Shoals, that’s where we sure can get gold.” (63)

A train whistle is heard moaning amongst the band’s introduction as Lizzie sings to her man:

“We got to catch the evenin’ train.” (64)

adding yet another two people to the latter-day ‘gold rush’. About 10 months after Lizzie Miles’ offering came a bouncing piano solo by an 18-year old Fats Waller who recorded it in New York City for Okeh. This was followed by another popular vaudeville-blues singer, Edith Wilson, cutting the third vocal “Muscle Shoals Blues”, in 1924 on the Columbia label; accompanied by white guitarist Roy Smeck posing as “Alabama Joe” to conceal his racial identity (a common practice at the time). There was a final version of this small group of songs about Muscle Shoals and the Wilson Dam. This was from Tennessee’s fine harp blower, De Ford Bailey – but as with Waller this is a solo instrumental piece cut, in April, 1927 for Brunswick Records. Fittingly, in chronological terms, the last song about this topographical phenomenon was the superb collaboration between Lucille Bogan and Walter Roland; inspired by the birth of the T.V.A.

This project was simply the largest and most ambitious an undertaking by any U.S. government. Embracing 7 states and crossing all political boundaries and mixing government control with private enterprise, its overall aim was to “master this foaming Goliath”, as Gunther put it, that was the Tennessee River; draining an area of “42,000 square miles” (65). This being the equivalent to the total landmass of Englandand Scotland combined. The T.V.A. Act of 1933 called for rural electrification, new agricultural techniques, as well as “the maximum amount of flood control; …development of the river for navigation purposes;…reforestation;…(and) the economic and social well-being of the people living in the river basin.” (66). Not only the people living there saw much improved opportunities for more economic stability but also those passing through on packets, towboats – and the railroad. The latter was after all the instrument in getting the subjects of Ms. Miles, Leola B. Wilson and Lucille Bogan’s blues to Muscle Shoals in the first place.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

IV

“Railroads, Steamboats, Chattanooga & the Lower Tennessee River”

The railroad did not come to the Tennessee Valley as a neat replacement for the steamboat – life of course doesn’t run like that, generally speaking. Steamboats were up and down the Tennessee and adjoining rivers well into the 1930s. But they had ceased to dominate their terrain by the beginnings of the 20th. century. Significantly, many towboats were transporting cargo that was for the ever-increasing extension of railroad building. The very lumber towed on the river was essential to the manufacture of freight and passenger cars, and also used for fuelling the many wood-burning locomotives still running around on the Southern rail systems. The GLADYS which was “Running in 1899…Towed lumber out of Decatur, AL.” (67). While the stern-wheeler DICK C. PAPE (built in 1910?) “Towed logs and ties out of (the) Tennessee River” until 1918. ‘Ties’ refers to crossties, or ‘sleepers’ in British parlance. The object that supported the twin iron/steel rails. Similarly, the HIBERNIA “towed cross ties and lumber out of (the) Tennessee River to Paducah.” (68). Many other towboats carried crossties, part of the railroad’s building blocks, out of not only the Tennessee but also adjoining streams such as the Cumberland and the Duck Rivers. These included the PETER HONTZ and the MARY A. ANDERSON. (69).

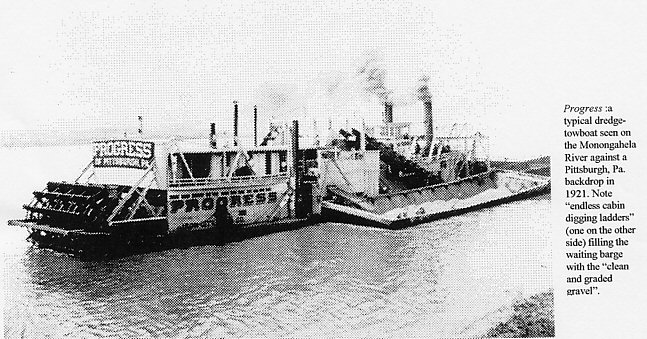

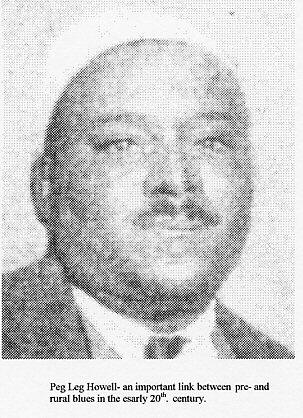

Just as essential to the railroad was the bed of ballast that the track and sleepers rested on. A myriad of companies had appeared by the early 20th. century including the Dixie Sand & Gravel Co. at Chattanooga, Tenn. and ran the T.R. PRESTON amongst others, as well as the Tennessee Valley Sand & Gravel Co. which ran the JAYHAWKER on the Tennessee in the early 1930s. (70). There was also the Sheffield Sand & Gravel Co. at the Wilson Dam No.1 which would have injected some money into the local economy, and partly compensating the failed government-owned nitrate plant from W.W.I If a gravel pit was not always on hand then often companies would have to send work crews to the foothills of nearby mountain ranges, including Lookout Mountain, to break up boulders to use instead of gravel-ballast. As Peg Leg Howell said in 1928.

“It take rock it take gravel to make a solid road. (x 2)

It takes a lovin’ fair brownie to satisfy my soul.” (71)

Howell, playing some soul-tingling bottleneck guitar equal to that of Charlie Patton, using the self-evident truth of his opening lines to strengthen the symbolism of his sexual desires. Howell who admitted, on his ‘rediscovery’ (in the early 1960s) picking up songs from anywhere, probably heard a guitarist thought to be from the Arkansas Delta-or his recording. Jim ‘Mooch’ Richardson had used a more explicit variation of this verse about a month prior to Howell’s “Rock And Gravel”.

“Takes rocks an’ gravel (to) make a solid road;

Take rocks an’ gravel make a solid road.

Take a great big engine (to) pull a heavy load.” (72)

Although B. & G.R. list Lonnie Johnson on a second guitar, I only hear one; and to these ears it sounds a lot more like Richardson. Any input on this discographical query would be more than welcome. Of course sand and gravel companies would normally dredge the river bed for this material, using specially equipped towboats.

From around 1900 railroads, such as the L. & N., “generally used…gravel or broken stone spread one foot in thickness over a space 10 feet wide.” (73). Other bases were used, for economic reasons, throughout the first half of the 20th. c. These included cinders, copper slag from furnaces, and chatt- or “metallic ore and rock” (74).

But once the railroad was established and operating, steamboats found a new source of employment – transporting the trains themselves (see p.2); at least until companies felt they could afford to build the necessary bridges. This was sometimes as late as the 1930s! Railroads often went into the steamboat trade themselves, the Illinois Central and Missouri Pacific among them. Another was the Nashville Chattanooga & St. Louis Ry. They sometimes utilised boats normally engaged in other duties such as towing ties. One of these was the WOOLFOLK. This was the stern-wheeler packet originally named CITY OF CHATTANOOGA (see p.5) and converted to a towboat in 1899. Named for “Montgomery cotton factor Joseph Washington Woolfolk” (75) who was not only into cotton but also railroad building. By 1887 he was president of the “Alabama Terminal and Improvement Company” (76). The WOOLFOLK “operated out of Paducah towing a railroad transfer barge…and in 1903, coal to Memphis for Paducah Coal and Mining Co….” (77). The N.C. & St. L. owned the GUNTERSVILLE and two versions of the HUNTSVILLE which were all “towing railroad transfer barges on (the) Tennessee River at Guntersville, AL.” (78).

Yet the railroad had been casting its long shadow over the steamboat trade as far back as the middle of the 19th. century. Even in a State like Alabama which had often been dragging its heels in adopting the ‘iron horse’; as Owen stated in 1921. From the time of Alabama’s admittance to the Union in 1819 as a State until the end of the Reconstruction Era in the late 1870s “…the political issue of public aid of internal-improvement schemes may be said to have remained the same…except for the substitution of railroad enterprises for river navigation projects about the year 1850.” (79) In fact the very first railroad in Alabama, (1832) was inspired by the ambition of its builders to find a viable alternative transport route which avoided Muscle Shoals. This was the Tuscumbia, Courtland & Decatur Railroad which had reorganised the earlier Tuscumbia Railway running since 1832 with horse-drawn vehicles. But largely due to the economic depression or ‘panic’ of 1837, the ultimate goal of reaching Memphis was not realised until a couple of takeovers down the line when the Memphis & Charleston included the pioneer railroad in its organisation. (see p.13).

Chattanooga was to embrace this changing attitude from about the same year when the State-owned Western & Atlantic RR. reached the city from Atlanta, Georgia. One of the earliest railroads in the U.S., founded in 1836, it was still referred to in the Blues of the 1920s, over 35 years after the W. & A. had been leased from the State of Georgia by the N.C. & St. L. In 1927, Peg Leg Howell again, here with the raucous fiddle of Eddie Anthony recalls a verse included two years earlier by Dora Carr and backed by Cow Cow Davenport, on a version of his famous “Cow Cow Blues”. Peg Leg & Eddie turn in a superb transposing of the Davenport piano classic.

“Some said the Southern, believe it’s W. & A., I’m-a gon’ get the first train that be goin’ out that way; Some said the Southern, I believe it’s W. & A., I’m gonna ride that first train I see goin’ that way.

Spoken: “The Dixie Flyer, boys.”

Unk. spoken: “You tell I’m a hobo ‘cos I got the Hobo Blues.”

“Train it left Cincinnati, goin’ to New Orleans;

Oughta seen your fireman stirring up gasoline. [This probably refers to the experiment of using oil-fired locomotives instead of coal in the 1920s. Only ‘oil’ doesn’t rhyme/scan with ‘New Orleans’ – Peg Leg Howell therefore employing some poetic license].

Oh! Train left Cincinnati, goin’ to New Orleans;

Oughta seen that fireman stirring up gasoline.”

Spoken: “The Dixie Limited, any kind of car.” (80)

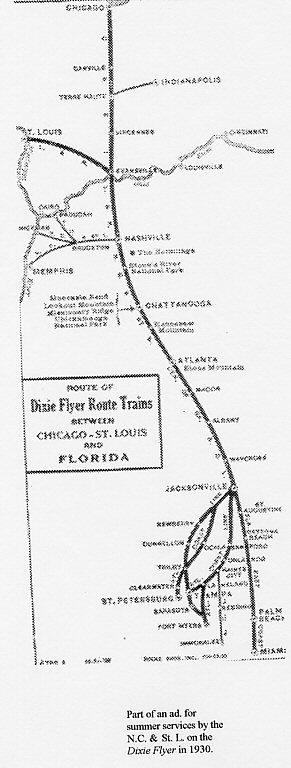

The Southern, the W. & A. and the N.C. &

St. L. all served Chattanooga and the latter instigated a series of “Dixie”

trains; starting with the Dixie Flyer in 1892 and followed by the

Dixie Limited in 1913. Initially running between Nashville, Chattanooga and

Atlanta; with “through Nashville-Jacksonville Pullman Drawing Room Buffet

Sleeping Cars that operated south of Atlanta…” (81) and

with the collaboration of several other railroads into Jacksonville, Fla. When

the N.C. & St. L. leased the old W. &

A. two years previously in 1890, the line became known as the Lookout Mountain

Route. By 1899 the Dixie Flyer, via a passenger traffic agreement with

the Illinois Central “was extended to St. Louis and Chicago via Martin, Tenn.,

Fulton, Ky., and the I.C.RR.” (82).

With this development Chattanooga became a veritable hub for railroads.

A hobo

like Peg Leg Howell (or a fare-paying passenger!) could reach major cities such

as Mobile, New Orleans, Memphis, Birmingham, Atlanta, St. Louis, and

Cincinnati. As Prince says “Chattanooga…offered the connections of the

Southern Railway System and the Central of Georgia Ry. for various points over the entire

South.” (83). The C.of G. having reached Chattanooga by 1905.

A hobo

like Peg Leg Howell (or a fare-paying passenger!) could reach major cities such

as Mobile, New Orleans, Memphis, Birmingham, Atlanta, St. Louis, and

Cincinnati. As Prince says “Chattanooga…offered the connections of the

Southern Railway System and the Central of Georgia Ry. for various points over the entire

South.” (83). The C.of G. having reached Chattanooga by 1905.

It

was Cincinnati, Ohio, which featured in several blues by Georgia singers

[Cincinnati had a thriving blues scene in the 1920s which

has been almost totally overlooked by historians with the notable exception of

“Going To Cincinnati” (A History of the Blues in the Queen City). Steven C.

Tracy. University of Illinois Press. 1993]; including at least 4 sides by Howell. The train he refers

to could well have been the Pan-American on the L.& N. Inaugurated in

December, 1921, “Trains 98 & 99” featured as a ‘crack express’ running from

Cincinnati via Nashville down to New Orleans. By the early 1930s the roar of

the train and its whistle were being recorded by local radio station WSM of

Nashville. Prince relates that this was a daily feature “except Sunday…through

the years up into the 1940s. If necessary, the following programs were

interrupted in order to bring through the actual live sound of Train No.99,”

(84).

However, the 2 recordings of “Pan-American Express” (Co unissued) and “Pan- American Blues” (Br 146, Vo 5180) by harp blower De Ford

Bailey would seem to suggest a slightly earlier vintage; as both were recorded

in 1927. Of course Bailey may have just heard the actual train (by then in

operation some 6 years) which inspired his recordings. Interestingly, he also

cut an unissued “Nashville Blues” and “Dixie Flyer Blues”; the latter which was

issued, being on the flipside of Brunswick 146 and Vocalion 5180. A passenger

could easily change in Nashville to the N.C. & St. L. for a short ride to

Chattanooga.

However, the 2 recordings of “Pan-American Express” (Co unissued) and “Pan- American Blues” (Br 146, Vo 5180) by harp blower De Ford

Bailey would seem to suggest a slightly earlier vintage; as both were recorded

in 1927. Of course Bailey may have just heard the actual train (by then in

operation some 6 years) which inspired his recordings. Interestingly, he also

cut an unissued “Nashville Blues” and “Dixie Flyer Blues”; the latter which was

issued, being on the flipside of Brunswick 146 and Vocalion 5180. A passenger

could easily change in Nashville to the N.C. & St. L. for a short ride to

Chattanooga.

But the importance of Chattanooga’s

geographical location as regard trade and commerce with the rest of the country

was realised from the earliest days of the W.&

A. which although in that city by 1849 was not completely connected from Atlanta until the

following year. South Carolinians and Georgians immediately recognised the trading potential of this new

railroad outlet on the Tennessee River. “The citizens of Charleston and

Savannah were quick to appreciate the importance of connecting their harbors with the productive districts of the interior, by railroads; and when these had penetrated their own States,

the line, of equal importance to both, was extended through Georgia into

Tennessee, connecting… Chattanooga with those cities.” (85).

By 1890 two Chattanooga businessmen, Russell Sage and C.E. James, had incorporated the Chattanooga Southern to “service the coal, iron

ore, and timber industries along its ninety-two miles, of main line track, which

paralleled the Alabama Great Southern

[The A.G.S. ran from Chattanooga to Meridian, Miss. and was merged with the

Southern Railway in 1895]

on the opposite side of Lookout Mountain.” (86).

They got as far as Gadsden, Ala. just a few miles south-east of Guntersville on

the lower Tennessee. This small railroad did not seem to be on any of the major

companies wants list and after a precarious decade of many re-organisations it

was “…reincarnated as the Tennessee, Alabama & Georgia Railway in 1911” (87). Its

initials led it to being affectionately known as the ‘TAG route’, and “the

Tennessee, Alabama & Georgia Railway remained independent,…through the first

half of the twentieth century.” (88).

But the importance of Chattanooga’s

geographical location as regard trade and commerce with the rest of the country

was realised from the earliest days of the W.&

A. which although in that city by 1849 was not completely connected from Atlanta until the

following year. South Carolinians and Georgians immediately recognised the trading potential of this new

railroad outlet on the Tennessee River. “The citizens of Charleston and

Savannah were quick to appreciate the importance of connecting their harbors with the productive districts of the interior, by railroads; and when these had penetrated their own States,

the line, of equal importance to both, was extended through Georgia into

Tennessee, connecting… Chattanooga with those cities.” (85).

By 1890 two Chattanooga businessmen, Russell Sage and C.E. James, had incorporated the Chattanooga Southern to “service the coal, iron

ore, and timber industries along its ninety-two miles, of main line track, which

paralleled the Alabama Great Southern

[The A.G.S. ran from Chattanooga to Meridian, Miss. and was merged with the

Southern Railway in 1895]

on the opposite side of Lookout Mountain.” (86).

They got as far as Gadsden, Ala. just a few miles south-east of Guntersville on

the lower Tennessee. This small railroad did not seem to be on any of the major

companies wants list and after a precarious decade of many re-organisations it

was “…reincarnated as the Tennessee, Alabama & Georgia Railway in 1911” (87). Its

initials led it to being affectionately known as the ‘TAG route’, and “the

Tennessee, Alabama & Georgia Railway remained independent,…through the first

half of the twentieth century.” (88).

Some 50 years before the beginnings of the TAG route, the Nashville & Chattanooga RR. had been chartered in 1845 and gradually made its way towards Chattanooga. After reaching the summit of Raccoon Mountain “the N. & C. RR. dipped down in Georgia through the future station of Hooker before reaching the valley again at Wauthatchie, Tenn. Then skirting the river bank around the foot of Lookout Mountain, the new railroad finally arrived at its southern terminal in Chattanooga.” (89). The date when service was opened was 11th. Feb. 1854. An even more important date occurred in May, 1858, when the innovative east-west line, the Memphis & Charleston RR. reached an agreement with the N. & C. over trackage rights which allowed it to take its trains into Chattanooga. This connected railroads between Memphis and the Atlantic coast for the first time with the cooperation of the W. & A. and several other roads. Cline quotes a glowing report by John Stover: “At Chattanooga, the state-owned Western & Atlantic was to link the Memphis & Charleston Railroad with other lines running to Charleston and Savannah, thus forming a continuous chain of railroads between the Atlantic coast and Memphis.” (90). It was on May 31, 1873, after several mergers with other roads that the N. & C. was changed to the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway. (91).

Despite blues singers as diverse as Blind Willie McTell and Ida Cox alluding to the N.C & St. L., there are no recorded examples that feature the Lookout Mountain Route, directly. The nearest are the several sides featuring the Dixie Flyer, Dixie Limited, and on occasion the ‘Dixie Line’; by which name this road was also known.

And of course, it

can be argued that as these trains ran under a ‘joint flag’ of six railroads,

any of the other five could also be the

subject of these particular blues references. As well as the N.C.

& St. L. there was the Chicago & Eastern Illinois, the L. & N., Central of

Georgia, Atlantic Coast Line and the Florida East Coast Railway. However, the

‘Dixies’ originated from the Tennessee road and it is the only one acclaimed the

‘Lookout Mountain Route’. The N.C. & St. L. took charge of these crack

expresses from Nashville via Chattanooga down to Atlanta and is definitely the

subject of Bessie Smith’s “Dixie Flyer Blues” in 1925.

And of course, it

can be argued that as these trains ran under a ‘joint flag’ of six railroads,

any of the other five could also be the

subject of these particular blues references. As well as the N.C.

& St. L. there was the Chicago & Eastern Illinois, the L. & N., Central of

Georgia, Atlantic Coast Line and the Florida East Coast Railway. However, the

‘Dixies’ originated from the Tennessee road and it is the only one acclaimed the

‘Lookout Mountain Route’. The N.C. & St. L. took charge of these crack

expresses from Nashville via Chattanooga down to Atlanta and is definitely the

subject of Bessie Smith’s “Dixie Flyer Blues” in 1925.

Spoken: “Hold that train”.

1. “Hold that

engine, let sweet mama get on board. (x 2)

‘Cos my home ain’t here, it’s a long way down the road.”

2. “On that choo-choo, mama’s gonna find a berth. (x 2)

Goin’ to

Dixieland, it’s the grandest place on earth.”

3. “Dixie Flyer come

on an’ let your drivers roll. (x 2)

Wouldn’t stay

up North to save nobody’s soul.”

4. “Blow your

whistle, tell ‘em mama’s comin’ too. (x 2)

Take it up a

little bit, ‘cos I’m feelin’ mighty blue.”

5. “Here’s my

ticket, please Conductor man. (x 2)

Goin’ to my

mammy way down in Dixieland.” (92)

Apart from this Bessie Smith recording, Peg Leg Howell’s “Hobo Blues” and DeFord Bailey’s harmonica solo (see p.12), seem to be the only ones referring to the train started by the Lookout Mountain Route way back in 1892. Other blues by pianists Leroy Carr, and Turner Parrish, together with popular banjoist Papa Charlie Jackson would appear to have a Dixie Flyer of a different kind from a more northerly state, in mind. But that’s another story.

Blind Willie McTell could have ridden

the Dixie Flyer from Chattanooga to Atlanta and by switching to another

Central of Georgia train

[That is to say another train rather than the Dixie Flyer which the C. o

f G. took over in Atlanta] headed on down to his regular base in

Statesboro, some 30 miles north-west of Savannah. Indeed,

apart from his reference to Lookout Mountain on “Drive Away some 30 miles

north-west of Blues” he mentions other locations such as Kennesaw Mountain on

his raggy “Atlanta Strut” (1929) which is just south of Chattanooga. And as

well as Atlanta on several sides, he also sings of Macon on his very moving

“Dark Night Blues” (1928). These locations are all on the N.C. & St. L.

From

the same session as “Dark Night” came one of McTell’s most awesome (and there

are so many!) performances,

“Three Women Blues” on which he brags about all ‘his’ women including “a Memphis yellow”. (93). The

N.C. & St. L. of course ran in a westerly direction from Nashville across

Tennessee to terminate in Memphis. It would appear that the Lookout Mountain

Route was one with which the singer was very familiar. Like Ida Cox, McTell

surely sang at various times that he too had ‘got the blues for Chattanooga’. And it is deemed fitting

to end this survey as it began; with a bluesman who was to Georgia what Charlie

Patton was to Mississippi and Blind Lemon Jefferson to Texas – Blind Willie

McTell, and Lookout Mountain. (but see Appendix ‘A’).

Blind Willie McTell could have ridden

the Dixie Flyer from Chattanooga to Atlanta and by switching to another

Central of Georgia train

[That is to say another train rather than the Dixie Flyer which the C. o

f G. took over in Atlanta] headed on down to his regular base in

Statesboro, some 30 miles north-west of Savannah. Indeed,

apart from his reference to Lookout Mountain on “Drive Away some 30 miles

north-west of Blues” he mentions other locations such as Kennesaw Mountain on

his raggy “Atlanta Strut” (1929) which is just south of Chattanooga. And as

well as Atlanta on several sides, he also sings of Macon on his very moving

“Dark Night Blues” (1928). These locations are all on the N.C. & St. L.

From

the same session as “Dark Night” came one of McTell’s most awesome (and there

are so many!) performances,

“Three Women Blues” on which he brags about all ‘his’ women including “a Memphis yellow”. (93). The

N.C. & St. L. of course ran in a westerly direction from Nashville across

Tennessee to terminate in Memphis. It would appear that the Lookout Mountain

Route was one with which the singer was very familiar. Like Ida Cox, McTell

surely sang at various times that he too had ‘got the blues for Chattanooga’. And it is deemed fitting

to end this survey as it began; with a bluesman who was to Georgia what Charlie

Patton was to Mississippi and Blind Lemon Jefferson to Texas – Blind Willie

McTell, and Lookout Mountain. (but see Appendix ‘A’).

Notes

1. “Drive Away Blues” Blind Willie McTell vo.gtr. speech.

26/11/29. Atlanta, Ga.

2. Bunce O.B. p.56.

3. Ibid. p.52.

4. “Chattanooga Blues” Ida Cox vo.; Lovie Austin pno.

July-Aug. 1923. Chicago, Ill.

5. Blassingame J. p.400.

6. Ibid. p.401.

7. Ibid.

8. White Jr. J.H. p.581.

9. Bunce. Ibid. p.60.

10. Ibid. p.p. 60-61.

11. Way Jr. F. & J.W. Rutter. p.199.

12. Ibid.

13. “Florida Bound Blues” Bessie Smith vo. speech; Clarence Williams pno.

17/1125. New York City.

14. Way Jr. F. p.51.

15. “Mama’s Got The Blues” Bessie Smith vo.; Fletcher Henderson pno.

28/4/23. New York City.

16. Capes J. C.D. notes Frog. Vol.1.

17. “My Monday Blues” Jim Jackson vo.gtr.

22/1/28. Chicago, Ill.

18. Oliver P. p.73.

19. Ibid. p.75.

20. “Oh-Oh Blues” Bert M. Mays vo. pno. c. -/11/27. Chicago, ill.

21. Dixon R.M.W. J. Godrich. p.357.

H. Rye.

22. Harris S. p.350.

23. Capes. Ibid.

24. “My Silver Dollar Mama” Hound Head Henry vo.speech; Cow Cow Davenport pno.

17/10/28. Chicago, Ill.

25. Harris. Ibid. p.144.

26. “Steamboat

Blues” Hound Head Henry vo., vo. effects, laughing, speech; Cow

Cow Davenport pno. 9/8/28. Chicago, Ill.

27. Ibid.

28. Korner A. E.P. notes.

29. Ibid.

30. Way Jr. & J.W. Rutter. Ibid. p.39.

31. Way Jr. Ibid. p.383.

32. Ibid. p.83.

33. Poole G. L.P. notes.

34. Ibid.

35. Foscue V.O. p.99.

36. Way Jr. Ibid. p.90.

37. Bunce. Ibid.

38. Way Jr. Ibid.p.311.

39. Bunce. Ibid.

40. Roget P.M. & J.L. & S.R. p..156.

41. Bunce. Ibid. p.p. 61-62.

42. Ibid.

43. Owen T.M. p.1063.

44. Ibid.

45. Lloyd J.T. p.47.

46. Owen. Ibid. p.1064.

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid.

49. Vanco J.H. C.D. notes “Coot Grant & Kid Wilson Vol.1”.

50. Ibid.

51. “Wilson Dam” Leola B. Wilson vo.; Blind Blake gtr. c. -/11/26. Chicago, Ill.

52. Ibid.

53. “New Muscle Shoals Blues” Lucille Bogan (as’Bessie Jackson’) vo.; Walter Roland pno.

20/7/33. New York City.

54. Ibid.

55. “Lost Man

Blues” Bertha Ross (probably Lucille Bogan) vo.; Vance Patterson

pno. 5/8/27. Birmingham, Ala.

56. Gunther J. p.734.

57. Wilson C.R. & W. Ferris (Co-Eds). p.369.

58. Gunther. Ibid. p.744.

59. Abbott L. C.D. notes “Lizzie Miles”.

60. Ibid.

61. Sward K. p.p.128-129. (quoted by Abbott. Ibid.).

62. Gunther. Ibid.

63. “Muscle Shoals

Blues” Lizzie Miles vo.; unk. tpt.; unk. clt.;

unk. alt. sax.; unk. vln.;

unk.pno.; unk.train whistle effects.c. 24/2/22. New York

City.

64. Ibid.

65. Gunther. Ibid. p.733.

66. Ibid. p.734.

67. Way Jr. Ibid. p.84.

68. Ibid. p.98.

69. Ibid. See p.p.157 & 182.

70. Ibid. p.121. & p.216. (and see list of companies).

71. “Rock And Gravel Blues” Peg Leg Howell vo.gtr. 20/4/28. Atlanta, Ga.

72. “Big Kate Adams Blues” Mooch Richardson vo.gtr. 27/2/28. Memphis, Tenn.

73. Herr K.A. p.369.

74. Ibid. p.378.

75. Cline W. p.174.

76. Ibid.

77. Way Jr. & J.W. Rutter. Ibid. p.243.

78. Ibid. p.88.

79. Owen. Ibid. p.1271.

80. “Hobo

Blues” Peg Leg Howell vo.gtr. speech;

Eddie Anthony vln. speech;

Henry Williams gtr. speech,.; or unk. speech. 1/11/27.

Atlanta, Ga.

81. Prince R.E. p.151. (“N.C.& St. L.”)

82. Ibid.

83. Ibid. p.173.

84. Prince R.E. p.147. (“L.& N.”)

85. Flint H.M. p.343.

86. Cline. Ibid. p.167.

87. Ibid. p.p.167-168.

88. Ibid. p.168.

89. Prince. Ibid. p.6. (“N.C.& St. L.”)

90. Stover. J. Quoted in Cline. Ibid. p.40.

91. Prince. Ibid. p.18.

92. “Dixie Flyer

Blues” Bessie Smith vo.; Buster Bailey clt.; Charlie Green tbn.;

Fred Longshaw pno.; unk. train imitation; unk. whistle.

15/5/25. New York City.

93. “Three Women Blues” Blind Willie McTell vo.gtr.speech.

17/10/28. Atlanta, Ga.

References

1. Abbott

Lynn. Notes to “Lizzie Miles Vol.1” (c.24/2/22-25/4/23). CD.

Document DOCD-5458. 1996.

2. Blassingame John W.

(Ed.). “Slave Testimony”. Louisiana State University Press. 1998.

(Rep.). 1st. pub. 1977.

3. Bunce

O.B. Quoted in “Picturesque

America” (Centennial Ed. 2 vols.).

William Cullen Bryant (Ed.). Lyle Stuart Inc. New Jersey.

1974.

3. Capes

Jonathan. Notes to “Bessie Smith – The

Complete Recordings”. Vol.1.

Frog DGF 47. 2004.

4. Cline

Wayne. “Alabama Railroads”. The

University ofAlabama Press.

1997.

5. Dixon Robert M.W. John Godrich. “Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943”.

Howard W. Rye. (4th. ed. rev.). Clarendon Press 1997.

6. Flint Henry

M. “The Railroads Of The United

States”. Arno Press. 1976.

(Rep.). 1st. pub. John E. Potter & Co. Philadelphia. 1868.

7. Foscue Virginia

O. “Place Names In Alabama”. The University of Alabama

Press. Tuscaloosa & London. 1989.

8. Gunther John. “Inside U.S.A.” Hamish Hamilton. London. 1947.

9. Harris

Sheldon. “Blues Who’s Who”. Da Capo.

March, 1989. (Rep.).

1st. pub.1979.

10. Korner

Alexis. Notes to “The Male

Blues-Vol.6.” E.P. JazzCollector JEL

10. Feb. 1960.

11. Lloyd James T.

“Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory & Disasters On The Western

Waters” Land Yacht

Press. Nashville, Tenn. 2000.

(Rep. with new intro. by Gregory G. Poole). 1st.

pub. 1856.

12. Oliver Paul. “Songsters & Saints”. Cambridge University Press. 1984.

13. Owen Thomas

McAdory. “History of Alabama & Dictionary Of Alabama Biography”.

(2 vols.). The S.J. Publishing Co. 1921. Chicago.

14. Poole

G. Quoted in notes to “Ed

Bell’s Mamlish Moan”. L.P. Mamlish

S-3811. Stephen Calt. Don Kent. Michael Stewart. c.1975.

15. Prince Richard

E. “Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway”. Indiana

University Press. 2001. (Rep.). 1st. pub. 1967.

16. Prince Richard

E. “Louisville & Nashville”. Indiana University Press. 2000

(Rep.). 1st. pub. 1968.

17. Roget Peter Mark. John Lewis. “Roget’s Thesaurus”. Tophi Books. Samuel Romilly. 1988.

18. Vanco John

Henry. Notes to “Coot Grant & Kid Wilson Vol.1” (1925-1928). CD.

Document DOCD-5563. 1997.

19. Way Jr. Frederick & Joseph W.

Rutter. “Way’s Steam Towboat Directory”. Ohio University Press.

1990.

20. Way Jr.

Frederick. “Way’s Packet Directory,

1848-1994”. (Rev. ed.). Ohio

University Press. 1994. 1st. pub. 1983.

21. White Jr. John

H. “The American Railroad Freight Car” The John Hopkins

University Press. 1995. (Rep.). 1st. pub. 1993.

22. Wilson Charles Reagan & William “Encyclopaedia of Southern Culture”.

Ferris. (Co-Eds.). University of North Carolina Press.1989.

23. All discographical details from “Blues & Gospel Records” Ibid.

24. Correction/additions by Max Haymes.

25. All transcriptions by Max Haymes unless otherwise stated.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Appendix ‘A’

There is a likely source for McTell’s ‘far-sighted’ reference to Niagara Falls in his “Drive Away Blues”. In November of 1940 the singer told Alan Lomax during a Library of Congress recording session that he played a lot of those “funny little shows” when recalling the travelling medicine show. While many of his peers/ contemporaries had cut their musical ‘teeth’ on this circuit Blind Willie gives the distinct impression he carried on playing for them for a far longer period – probably well into the 1930s. This would help supplement his income in the absence of a ‘hit record’. In his revised edition of the fascinating “Step Right Up”, Brook McNamara says in the 1995 preface that he made three additions to his original book from twenty years earlier. One of these was a medicine show act or ‘bit’ as he called it, known as “Niagara Falls”. This was one of the four “perennial favorites known to every medicine show performer and virtually every small-town boy of the early twentieth century.” (1). The author says that “Probably all four had their origins in the afterpieces that closed the nineteenth-century minstrel show.” (2). Most likely performed in blackface, the writer’s source was a “Carolina string band The Hired Hands” (3), who he saw perform it at the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife in 1981. This bit was performed by three men: a straightman, a heavy comic and a light comic. (4).

In the version quoted, the setting is a street corner and the straightman relates to the audience how he is not feeling too good because of an event that happened to him recently. Basically, a friend of his said he wanted to treat him to a vacation and pay his fare. “all the way”. (5). It soon turns out that rather than actually going on this vacation to the U.S./ Canada border, the straightman Homer ‘Pappy’ Sherrill, says he’s told by his friend that this will “be kind of an imagined thing” (6). After eulogising about the coolness of the breeze, the mist of the falls and “the water flowing over the dam” (7) his friend said to Pappy “ I’m gonna ask you to put this little thing called a radio funnel into the front of your pants, and I want you to imagine that you’re on your vacation.” (8). So, Pappy relates, “I did that and he let me have it – he poured a lot of water in my britches. I kind of got a little angry with him. He said, ‘Don’t do that, it’s all in fun. Get the next man that comes along, and have your laugh on him. So I’ve been waiting for the moment when he comes along, and…here he is!” (9).

In comes ‘Greasy’ who is the heavy comic and Pappy successfully tricks him with the Niagara Falls story. Pappy, in his turn, tells the unfortunate (and very wet) Greasy he can perform this bit on the next man that appears on the scene. This brings in the light comic, ‘Snuffy’, who goes along with the act. But strangely, even after pouring glass after glass into the front of his trousers, Greasy cannot see even a trace of damp on his intended victim. The latter who has been told to stare at a buzzing fly during this event to distract his attention, is finally asked by an exasperated Greasy “You don’t feel like you been to the falls? You don’t feel a little damp way down there in your bottom? (Snuffy replies) No, buddy, I been to Niagara Falls before!” (then) “Snuffy pulls a hot water bottle from his pants, into which all the water had been poured. Greasy and Pappy shout in surprise, and all make a quick exit.” (10). This was performed, with plenty of belly laughs and wisecracks all over the middle West and the South, including not only North Carolina but McTell’s home state of Georgia too. Blind Willie McTell could not have failed to be aware of this top medicine show bit called ‘Niagara Falls’ and it may have helped focus his mind when putting lyrics together for his “Drive Away Blues”.

Notes

1. McNamara B. p.138.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid. p.xviii.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid. p.200.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid. p.206.

Reference

1. McNamara

Brook. “Step Right Up”. University Press of Mississippi. Jackson.

1995. (Rep.). 1st. pub. 1975.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Appendix ‘B’

As with many early blues there was a considerable amount of cross-fertilization with their hillbilly counterparts – and not always from black to white. Ida Cox’s “Chattanooga Blues” was covered by the Allen Brothers in 1927, still singing from the original female perspective; a not uncommon practice by blues singers also. (see Table 1).

Table 1

1. Chattanooga Blues Ida Cox 1923

2. Chattanooga Blues Allen Brothers 1927

3. Johnson City Blues Clarence Green 1928

4. New Chattanooga Blues Allen Brothers c.1929

5. Chattanooga Mama Allen Brothers c.1930

6. Chattanooga Mama Allen Brothers 1934

Although Austin Allen, who probably takes the vocal, omits the ‘Lookout Mountain verse’, he does include variations of a couple of Ida Cox’s other stanzas. This included my dubious ‘float on the falls’ transcription. Strangely, Allen’s diction seems no clearer than that of the “Uncrowned Queen of the Blues”! At least here I am a little more sure of the last two words, ‘float’ is still muddied. Yet he appears to sing Ida’s lines word-for-word. The fact that the Allen Brothers (often known as “the Chattanooga boys”) were from Chattanooga probably accounts for their four versions of this song made between 1927 and 1934. I only have two of these, the other one being “Chattanooga Mama” from their last session. Taken at a far slower pace than their superb 1927 recording, this sounds quite lacklustre by comparison and omits all Ida Cox verses and still no reference to Lookout Mountain.

In the year after the Allen Brothers’ “Chattanooga” another hillbilly version appeared by guitarist Clarence Green. He uses Ms. Cox’s ‘Lookout Mountain verse’ plus the one including ‘float on the falls’. But Green, who gives an excellent performance, had even more problem with the blues singer’s diction than I did and mis-pronounces Chickamauga, to boot!