Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

The English Music Hall Connection |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As has been noted in the previous chapter, the earliest English music hall artist to record in New York was Julian Rose, and he included "Ain't Dat A Shame" issued on an Edison cylinder in 1903. Some 27 years later, the gravelvoiced pianist, Peetie Wheatstraw recorded "Ain't It A Pity And A Shame" for Vocalion. Wheatstraw was one of the most influential Bluesmen in St. Louis in the 1930's and lived across the Mississippi River in East St. Louis; a sprawling slum and the scene of one of the most horrific race riots, in 1917. Another pianist, Sunnyland Slim, recalled that in the early 1930's in St. Louis "....Peetie Wheatstraw was raisin' sand. Him and Walter Davis was the big names then."(2). It is Davis who would seem to be inspired by a Florrie Ford title from 1910, "Tis A Faded Picture". In 1940, he sang, to his own deceptively simple, yet actually very complex piano accompaniment:

Over ten years later, an East Coast guitarist, Carolina Slim, was to continue the theme, obviously based on the Davis title:

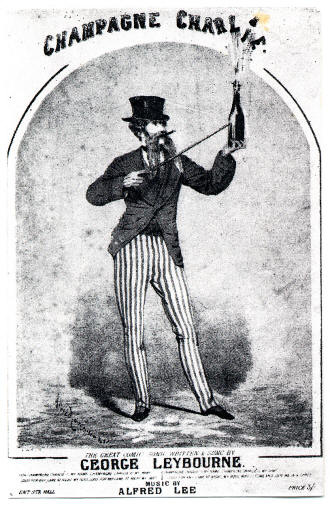

Though his version, "Your Picture Done Faded"', is slightly more optimistic (or more ominous), as Slim sings "I'm gonna find that woman, that caused me to weep an' moan". One of the pre-ragtime songs, Oliver refers to, that did appear to survive in the Blues, was "Christmas Day in the Workhouse" (1877) "...written by G.R. Sims"(5). In 1929, Leroy Carr recorded his "Christmas In Jail--Ain't That A Pain?", and early the following year "Workhouse Blues". The latter was probably a belated cover of the Bessie Smith record of the same name in 1924. Famous folk and blues singer, Huddie Ledbetter ('Leadbelly'), was to cut his "30 Days In The Workhouse"' in 1935. Meanwhile, back in England in 1930, Billy Bennett had recorded "Christmas Day In The Cookhouse". Carr, as well as having many beautiful Blues sides issued, also recorded other material including vaudeville and pop songs. Intriguingly, one which remains unissued is "Girl In Blue" in 1928. If this is indeed a version of "The Dark Girl Dressed In Blue" (see see Ch. II), as seems likely, then it is yet another example of a pre-ragtime music hall influence on the Blues. The latter song was a hit for George Leybourne around 1865 and also for Harry Clifton in the same period. "Workhouse Blues" was to reappear in 1935 by yet another pianist from St. Louis, one of the Sparks brothers, calling himself "Pinetop". The title alone lending a decidedly Victorian air to this particular blues. Another St. Louis-based Blues singer in the 1930's, was guitarist Charlie (or Charley) Jordan. A contemporary of Peetie Wheatstraw, with whom he often played and recorded, Jordan cut a blues with the unlikely title of "Twee Twee Twa", which he included in his last verse:

The phrase in question, here used in a frankly sexual context, entirely in keeping with the Blues, appeared some five years earlier in 1932, by Jack Payne and his Band in a humorous, "How Am I Doin'? (Hey Hey)", with a British air of jollity so typical of the genre. This recording features the phrase "twee twee twa" in a scat vocal setting; that is to say, a meaningless group of words which are sung within the musical framework of the song in question. The scat vocal had been popularised by early American jazzmen in the 1920's. and in particular by the then youthful Louis Armstrong. Leaving St. Louis, we find themes, titles, and words from the English music hall which reappeared in the Blues from singers all over the southern states. Florrie Forde, once again, recorded "Easy Street" in 1905 and in 1928, Texas Bluesman Henry Thomas cut "Texas Easy Street Blues" accompanying himself on guitar and reed-pipes in a very early country manner. The very popular medicine-show entertainer, Jim Jackson a resident of Memphis, recorded "I'm A Bad Bad Man" also in 1928, which echoed a music hall hit of 1920 vintage "I'm A Bad, Bad Coon" by G.H. Elliott. Another Elliott title, made some five years earlier, "All Girls Look Alike In The Dark" was to reappear in Papa Charlie Jackson's first ever record for Paramount in 1924, albeit in a different guise:

His lines containing references to a gradation of colour within black

society in the U.S. This colour-caste system ranged from 'black' through

brown to the lightest-skinned or 'yellers'' (yellows). Virtually nothing

is known of Jackson other than the 'fact' he died in Chicago in the late

1930's and that he was originally from New Orleans. Using a

guitar-picking approach to his banjo, most of his 60odd recordings

(1924-34) were more to do with the pre-blues scene and included comic

songs, as well as pop numbers, 'straight' blues and vaudeville tunes. A

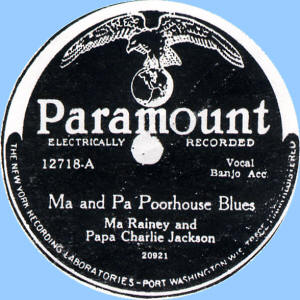

duet he recorded with Fig 1: The 1928 record by Rainey & Jackson

As Harry Fay's 1911 version of "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was covered by one of the most famous vaudeville blues singers, Bessie Smith some fifteen years later in 1927, it seems reasonable to assume (without having access to the record in question), that Albert Whelan's 1906 song "The Preacher And The Bear" was also the same as the one by Virgil Childers in 1938. The latter was a guitarist from the Eastern seaboard, possibly North Carolina. Bastin, on the strength of other recordings, suggests that "Childers could well have been white,"(11). Links between the English music hall and the Blues, of whatever shade, can be seen in "My Meatless Day" by Ernie Mayne in 1917 and the lines in Blind Lemon Jefferson's "Rabbit Foot Blues" of 1926 which refer to those "meatless an' wheatless days". Jefferson was a primary Bluesman and one of the most influential, from Wortham in Texas. Also the English hit in 1923 "Yes We Have No Bananas" was recorded by vaudeville blues artist Eva Taylor as "I've Got The Yes! We Have No Banana Blues" (sic), later the same year in New York City. Back in London in November of 1912, Mark Sheridan cut his "They All Walk The Wibbly Wobbly Walk". It would seem he borrowed the latter part of the title from a Marie Lloyd record made some five months earlier "Every Little Movement Has A Meaning Of Its Own", in which the celebrated singer included the 'wibble and wobble' phrase. Nellie Florence, a 'dirty-voiced' singer from Jacksonville, Florida, commences one of her blues:

A 1904 title called "Encyclopedia Britannica" (The Woman Who Knows) by Malcolm Scott uses the spoken format "Now we come to the letter L" etc. This same format was picked up in Blues circles. Bessie Smith sings:

Mellers says Bessie .Smith, as a child "...worked in travelling tent-shows and circuses, so she was a professional music-hall artist who preserved some of the qualities of a folk-singer."(14). The phenomenon of the 'laughing record' even spread across the Atlantic. This phenomenon goes back to the earlier days of English music hall, as Newton illustrates when discussing a popular comic from the 1860's, "Jolly Nash". "Nash having cultivated a most infectious laugh--or series of chuckles--became known as the "Laughing Comic",(15), and some of his ditties lasted for years. "They included "I couldn't help laughing, it tickled me so!", "The Little Fat Grey Man", and "Ho! Ho! Ho! He! He! He!""(16). Following on in this vein was Charles Penrose who had recorded a string of laughing records as early as 1911, some under the pseudonym "Mr. Harry Happy". But his best remembered song comes from a later session in 1922, entitled "The Laughing Policeman". Penrose went on to re-record "Policeman" along with many 'sequels' up to as late as 1933. On 7th March, 1923, vaudeville blues singer Viola McCoy recorded "Laughin' Cryin' Blues", apparently a "dreadful 'novelty' number"(17). But with her fine voice "Miss McCoy somehow manages to make the awful lyrics bearable, and even her laugh in the middle section comes off, it is so perfectly timed."(18). This opinion of the record notwithstanding, the singer re-recorded it nearly three weeks later under the name 'Amanda Brown' for a different company; both versions were issued. Some of the 1934 recordings of the Memphis Jug Band feature the raucous laugh of one of its members, guitarist Charlie Burse, to be heard on "Take Your Fingers Off It", "Little Green Slippers" and "Bottle It Up And Go", amongst others. Charters observes that "The laugh, often in the same rhythm as the accompaniment, seems to have come from the minstrel and vaudeville stage and was very popular in the first years of the blues recordings."(19). The 1934 titles are all in an up-tempo, good-time blues, hokum style; but the laugh also appeared on some of the more intense, introspective blues of a rural singer such as Charlie Lincoln, a Georgia singer, who played a twelve-string guitar and prefaced some of his blues with a sardonic cackle; as on "Jealous Hearted Blues" or "Hard Luck Blues" from 1927. Charters refers, rather tongue-in-cheek I feel, to Lincoln's "...distinctive "laughing" style..."'(20). The following year, Lincoln was in the recording studio when Nellie Florence made her "Jacksonville Blues" with Lincoln's younger brother, "Barbecue Bob" also on a twelve-string guitar. On hearing the words:

Lincoln bursts into laughter that can best be described as maniacal! This so amused Ms. Florence that she, almost inaudibly, requests him to do "''nother" prior to repeating the verse near the end of her blues. The rough-voiced Tommy McClennan from the Mississippi Delta who recorded between 1939 and 1942, sometimes inserted a menacing chuckle into his songs, which was entirely in keeping with the atmosphere he created with his limited yet totally effective guitar playing. Even in the post-war period (after 1943) an example cropped up in the Blues, which wars an almost direct imitation of "The Laughing Policeman". Dan Pickett, an excellent guitarist from Alabama, recorded "Laughing Rag" in August, 1949. His title shows a remarkable tenacity in the continuation of but one facet of the Blues; that of the influence of the English music hall. As I have already said, not only themes and songs crossed over from the latter to the Blues, but also occasionally a word would make the same journey. Taking one example, the word 'donah' (a woman/lover) flourished in the East End of London in the nineteenth century, and this was reflected in songs featured on the halls. 'Donah' transferred to the U.S. and the Blues, though oddly appearing on record until the 1930's. Before citing some examples, it is worth noting some definitions from both sides of the Atlantic. Partridge lists "dons, donah, (mostly in sense 2), donner, doney, rarely donnay. A woman; esp. the lady of the house: from the 1850s: Cockney and Parlary."(22). The term 'Parlary' refers to a mixture of languages as slang, the "vocabulary of C.18-mid-19 actors and midC.19-20 costermongers and shoumen: (orig. low) toll."(23). Interestingly, Partridge lists "dona Highland -flinger" as pre-1909 rhyming slang for "A music hall singer:"(24). In terms of the given social strata, the word sinks to its lowest level, from the same period, as 'dona Jack' ,which describes "A harlot's bully:"(25). Continuing on this level, Calt and Wardlow quote Mississippi Blues singer Son House who says "a donnay" is "...a no-good woman."(26). This is also the definition by a pianist, Jasper Love, also from Mississippi. When Blues writer William Ferris asked him "What's a doney?" Love replied "That's what we call a no-good woman."(27). Bob Groom thinks doney "...apparently derives from the word 'donna'..." (28), and has Spanish/Italian roots via England. This reflects back to Partridge's 'Parlary'. As "donah", the word features in several English music hall songs. On 23rd. February, 1899, Gus Elen recorded "The Faifless Little Donah" and "Never Introduce Yer Donah To A Pal" in London. Elen (b.1862) was a comedian and singer and "probably the greatest of the select band of coster comedians of the 1890's," (29). The latter song was one of Elen's many hits. Around the same time, Vesta Victoria included in her repertoire "All In A Day" composed by Joseph Tabrar. Part of one verse runs:

Albert Chevalier's 1898 record "The Future Mrs. 'Awkins" contains the lines:

No doubt, causing feminists everywhere to gnash their teeth!! Further to this, Chance Newton, himself a product of the London music hall from the 1860's, describes a young man about to pick up his girl-friend on the way to the local sing-song, as a "dandy crook dressed up fit to kill, and certainly to paralyse", his donah,"(32). Across the Atlantic, the term was sometimes corrupted to 'dony'. The word, in black parlance, c. early 1920's, often referred to a lover, as a singer explained to sociologist, Howard Odum: "A girl was luvin' a nigger, an' she thought he did not go to see any other girl; she found out he did, an' she made a hole in the wall of her house so she could watch an' see did her lover go to see any other nigger." The lover makes a song:

Calt and co. acquired a. definition of 'donnay' as they transcribed the archetypal Mississippi singer, Charlie Patton, singing in 1934:

What Patton actually sings is:

Over two years later, still with Mississippi, the 'tortured' Robert Johnson, now a cult figure in the 1990's, sang:

Almost the same verse was used more than fourteen years later, in the early 1950's by Elmore James on his "Dust My Broom". A contemporary of Muddy Waters, James was also one of the main idols in post-war Chicago blues circles, and was originally from Canton, Mississippi. The later style of Blues featured heavy electrification in the instruments and stayed more closely to the 12-bar framework. This was the immediate precursor of rhythm and blues, rock 'n roll, rock, heavy metal, etc. In the 1960's, two more singers from the same state, Do Boy Diamond and R.L. Burnside, both recorded "Long Haired Doney" for the American Arhoolie label. Both of these performed Blues in the earlier rural style accompanying themselves on guitars. Strangely, the term "doney/doner" does not seem to crop up in any other Blues from the 1920's. Why it should appear (or reappear?) in 1934 and on into the 1960's as the domain of Mississipni singers, must, for the present, remain one of the mysteries of the Blues. As referred to earlier, Blues writer Paul Oliver mentions one exception in the way of pre-1870 songs of the music hall being recorded by black songsters. His example is "'..."Champagne Charlie", which dates from as early as 1868..."(37). Although Pulling says George Leybourne "...made his "Champagne Charlie" the rage when he first sang it in 1867."(38). There were other exceptions, already noted, and "Sally" is a further one to be dealt with shortly. Some of the original English version of "Charlie" runs:

Leybourne was from a working-class background, like most of the music hall artists, but he adopted the suave image of the upper-class 'swell' with the greatest of ease. He had many other hit songs on the halls but his name is synonymous with "Charlie". As one writer puts it "Leybourne's hit song "Champagne Charlie" has never been forgotten and the wine merchants at the time provided him with free champagne at a cost to them of £20.00 per week."(40). (see Fig.2.). The song soon travelled across the Atlantic where in New York it became Americanised as Pulling has already claimed:

The Blues singer's a-typical use of the early sounding 'rovin' acknowledging perhaps the song's English origin. "Stealin '" is often used in black speech to signify creeping away in the small hours from a married woman's bed, implying a 'love 'em an' leave 'em' policy; thus belies the reference to "true love" in the opening lines. Another pre-1870 song which, if it did not reappear in its entirety in the Blues, certainly contributed a lot of inspiration for the latter. The title of this song is "Sally in our Alley" written by "Henry Carey c.1687-I743"(43). The first verse of this song, runs:

Lloyd tells us that Carey wrote "The ladies' case" "...a stage song of 1734,"(45), so it is possible he wrote "Sally in our Alley" around the same time; also for the stage. In any event, a version appeared in 1922, again for the stage-the music hall stage this time, in the shape of a recording on the Regal label; "Sally (The Sunshine Of Our Alley)" by Fred Barnes. But it was a song about Sally, some nine years later, by Gracie Fields which, I contain, spread its influence across Atlantic into the world of the Blues. The future star was already making a big impression, not only in the North of England but in London music halls as well. In 1928 "There was even a trip to New York, to sing at the Palace."(46). Kennedy adds that "'Sally' was a bit of a curiosity, since it sounds very like a song a man should sing, yet it was Gracie's signature tune. She sang it in her film debut "'Sally in our Alley"(47). Busby elaborated a little: "While appearing at the Metropolitan, Edgware Road, in 1931 she bought the song 'Sally' from composers Leo Towers, Bill; Haines and Harry Leon. It became her signature tune, inseparable from her name ever since."(48). So there would appear to be either two songs, "Sally" and "Sally In Our Alley", or Towers and co. hijacked the older tune. Whatever the truth of the situation "She made her first film, "Sally In Our Alley", 1931, which led to a series of highly successful films made both in England and Hollywood,"(49). In a medley of her hits, in 1934, Gracie included a segment of her most famous song, first recorded a year earlier:

Since this song would have gained exposure in the U.S.A. from 1931 onwards; a logical appearance in the Blues (if there was going to be one) would be around this time. In March the following year, sure enough, famous Blues guitarist Big Bill Broonzy (recording as "Big Bill"), included the following verse in his swinging "How You Want It Done?"

Just over three years later, an older singer put his version on disc:

Featuring the same fast accompaniment, but not as skillfully as Broonzy, the Lasky item "...may in fact have been the parent piece."(53). Both versions of course; are blatantly sexual; 'jelly' referring to the female genitalia and by extension 'jelly roll' (thus 'rolling') meant sexual intercourse. The Blues singer drawing on his environment for imagery; in this case the sweet-meats and other confectionery to be found at the baker's shop. Ms. Fields' recording manager would probably have been horrified by such lyrics (and possibly Gracie too!). In the previous year, 1934, a superbly sung Blues that reeks of danger is delivered by another top-rate singer, Lucille Bogan, whose vocal can best be described as 'smouldering'!

Meanwhile back in 1935, another excellent guitarist recorded his "Alley Sally Blues". In this instance, Sally is a bootlegger of some potent booze:

It would seem to be certain that these examples in the Blues are not just coincidence. They all cropped up on wax within four years of Gracie's "Sally in our Alley" being shown in Hollywood. So far I have not come across any 'alley-Sally' references in a blues record made before 1931; during the course of the last thirty years! Although these blues recordings seem to be inspired by the Gracie Fields song, there is a clear, if indirect, link with Carey's composition in the 18th. century.

A song of more recent vintage is "Who Were You With Last Night?" written by Fred Godfrey and Mark Sheridan in 1912. Although Sheridan was to put his own version on record in November of that year, another music hall artist beat him to the studio. Albert Whelan was there first, in October. The chorus goes:

In the Blues it became a 'hokum' item. Or put another way, good-time blues. In 1930, Georgia Tom and Jane Lucas traded jibes and insults in their "Where Did You Stay Last Night".

Although "Georgia Tom" (Thomas A. Dorsey) claimed authorship, and he was a prolific writer, this song was obviously very much influenced by the English music hall item. Once more, the Blues has lyrics which are more explicit; even the subtle title change from asking 'who you were with' to 'where did you stay?' transforms the song from a possibly 'naughty' evening out into a very definite steamy, all-night love affair. Dorsey, was to become a. major factor in the change of style in black gospel music from the early 1930's onwards, composing such popular titles as "Peace In The Valley" and "Precious Lord, Take My Hand"; versions often crossing the colour line. But before his total conversion he recorded many vaudeville/music hall numbers, risque songs, and blues, often in collaboration with ace slide guitarist, Tampa Red. "It's Tight Like That" from 1928 being their best seller, and most recorded song. Another music hall title interested him enough to make him want to record it. In December, 1922 Norah Blaney and Gwen Farrer recorded "Second Hand Rose" which commences "Father has a business, strictly second-hand," and perpetuates the theme "I never get a thing that ain't bin used"; even a plumber's amorous attentions, soon reveal that he was married before! Picking up on the latter subject (of love-relationships), Georgia Tom declared "Give me anything but secondhand love." on his 1930 recording of "Second-hand Woman Blues". Three years previously, Margaret Johnson had retained more of the content of the Blaney and Farrer (who may have been American) number in her "Second-Handed Blues", although the pianist, possibly Mike Jackson, claims composition rights. Johnson transforms the opening line to "The man I got runs a second-handed store." But the theme remains the same:

Margaret Johnson was one of the vaudeville-blues singers, albeit with more than a hint of rural origins in her vocal and accompaniment. The English music hall influence made itself felt in a more implicit way than just a transfer of certain songs. But according to Stewart-Baxter it would seem this influence was only too obvious and to the detriment of the 'classic'/vaudeville-blues. This writer, often quite rightly, complained of the scant coverage by Blues collectors of even the best of the singers in this genre. "As they sing ballads and vaudeville songs and are, more often than not, accompanied by jazz musicians, they are condemned without trial...It is, I believe the vaudeville influence which is the drawback, and both purist and modernist (Blues collectors and fans) will ignore the very idea of a music-hall based vocalist."(59). But as he adds "...it should be realised that these women were performing for their own people: it was for the black public they were singing."(60). Or more precisely, the black working-class public. In much the same way as the music hall singers performed, primarily, for the British working-classes across the water. Although the latter were fast disappearing, as were the halls themselves, by the time Mamie Smith made the historic first Blues record "Crazy Blues" in 1920. The vaudeville-blues, as they are more correctly called, have in their content "... a proportion of the worthless, the mechanical, the contrived, but there is also a gaiety, a vitality, a sense of good time!"(61), according to George Melley, and this is summarised by Stewart-Baxter "In short, the classic blues singer was a stage performer who came up with the glorious music hall tradition."(62). One of the pioneer singers and therefore a contemporary of Mamie Smith, was Lucille Hegamin. Of whom it was said, "Lucille's clear, rich voice, with its perfect diction, and its jazz feeling, was tall in the vaudeville tradition and her repertoire was wide. With all the music-hall overtones, she was still an extremely good singer of jazz-based blues,"(63). Many of the English music hall artists had vocal styles of similar qualities. Baxter classifies two rough categories of the vaudeville blues singers: "those who lean very heavily on the music-hall, vaudeville and cabaret for their inspiration,...and the more blues-based rural singers..."(64). However, he admits that "...every so-called Classic singer showed, to a greater or lesser degree, the debt she owed to the music hall and cabaret."(65). It is interesting to note, in passing, that the vaudeville blues was essentially a female preserve. Intriguingly, it was the vaudeville blues that had the strongest affinity with the English music hall, via the women singers. Singers like Marie Lloyd, Gertie Gitana, Ella Retford and Hetty King often portrayed vocal styles, depending on the song, of similar sounding material to that of Mamie Smith, Edith Wilson or Lucille Hegamin. All these singers come into Baxter's first 'rough category' of music hall inspired artists. "I'm Going Away" by Hetty King, in May 1909, in style of vocal delivery and song formula, pre-dates the great Ma Rainey who was to start recording some 14 years later. Although Ms. King's voice can in no way be likened to the great Blues singer's. In 1915, Ada Reeve recorded "Nobody Knows, Nobody Cares". The first part of this record is sung in almost a Blues context, with Ada employing falsetto (a popular Blues-singing vehicle) in places. She also includes the essentially Blues line: "my heart achin' and almost breakin'". Around 12 years earlier, Vesta Victoria's "Riding On A Motor Car", in feeling, and with lines of double entendre like "now Jim has a broken limb, and I haven't had me honeymoon yet", has parallels with many vaudeville blues made more than twenty years later. Whereas, as we have seen, the male artists on the English music hall circuit impressed the Blues via their material and lyrics, that the black singers incorporated either in part or sometimes in their entirety. The influence of the English music hall can now be seen in a far more positive light than has been perceived by Blues collectors and writers in the past, and must be counted as one of the major ingredients in the rich recipe that was and is the Blues of the American, working-class, black citizen. Notes

1.Oliver.P. "Songsters etc. ibid, p,p,47-48.

Illustrations

All Blues transcriptions by Max Haymes. 1991. Except item by Georgia Tom.

Dr, Hans R. Rookmaaker. 1963. Also "Preachin' The Blues" by Bessie Smith.

Paul Oliver. 1968. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Website © Copyright 2001-2008 Alan White. All Rights Reserved.

Text (this page) © Copyright 1992 Max Haymes. All Rights Reserved.

For further information please email:

alan.white@earlyblues.com

one of the finest of the vaudeville blues singers,

Ma Rainey, was in the latter vein. It invoked the workhouse theme again

which appeared in the title as "Ma And Pa Poorhouse Blues". As

Stewart-Baxter put it, this number "...is full of backchat and

music-hall hokum."(8). Describing her down and out condition,

Ma Rainey moans, as only she could, "Ohhhhh-ohh, here I am on my knees,"

Jackson cheerfully reassures her "Don't Worry Ma, I'll soon be down on

my knees wit ya."(9). In 1912, Jen Latona recorded "Your Daddy Did The

Same Things Fifty Years Ago" on a foggy November day in London. Some 18

years later, one of the greatest of all rural Blues singers, Memphis

Minnie adapted the title in a Chicago autumn:

one of the finest of the vaudeville blues singers,

Ma Rainey, was in the latter vein. It invoked the workhouse theme again

which appeared in the title as "Ma And Pa Poorhouse Blues". As

Stewart-Baxter put it, this number "...is full of backchat and

music-hall hokum."(8). Describing her down and out condition,

Ma Rainey moans, as only she could, "Ohhhhh-ohh, here I am on my knees,"

Jackson cheerfully reassures her "Don't Worry Ma, I'll soon be down on

my knees wit ya."(9). In 1912, Jen Latona recorded "Your Daddy Did The

Same Things Fifty Years Ago" on a foggy November day in London. Some 18

years later, one of the greatest of all rural Blues singers, Memphis

Minnie adapted the title in a Chicago autumn: In 1932 Blues guitar virtuoso, Blind Blake adapted the song once again,

for working-class black listeners. The incongruity of one of them

sipping Champagne in those Depression-torn times, would have great

appeal, causing many a sardonic smile:

In 1932 Blues guitar virtuoso, Blind Blake adapted the song once again,

for working-class black listeners. The incongruity of one of them

sipping Champagne in those Depression-torn times, would have great

appeal, causing many a sardonic smile: