Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

I Need-A Plenty Grease In My Frying Pan |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

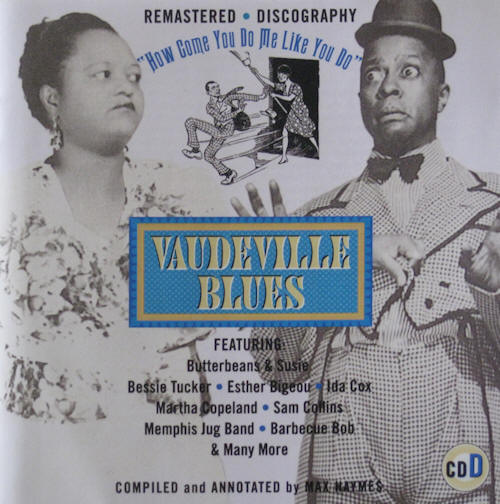

CD D - You Was A Good Old Gobbler, But You Lost Your Strut In 1938, an excellent string band, for that is what it was, came together in the recording studio to lay down just six titles for the Bluebird label. The 2 accompanists loomed large on the stage of rural and urban blues. They were Sonny Boy (John Lee) Williamson on harmonica and Yank Rachell playing mandolin. Of course, the catalogues are sprinkled fairly liberally with recordings in their own right as well as being listed as support for other blues artists. But the singer on this session, sometimes known as ‘Jackson’ Joe Williams, stepped into the limelight ever so briefly. [Footnote 22: The 2 sides on Vocalion 1457 from 1929, listed under this Joe Williams’ name by B.& G.R. (p.1040); are in fact by Kansas Joe McCoy with Jed Davenport on blues harp.] A competent guitarist, Williams was also from Tennessee as were his accompanists. He was also a friend of his much more famous namesake Big/Poor Joe Williams (of ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ fame) and appeared to be part of the coterie from the region in an around Jackson, Tennessee, in the 1930s. Jackson Joe’s finest moments are his take on a previous Blind Lemon Jefferson number about a ‘peach orchard mama’, and his driving adaptation of ‘Sloppy Drunk Blues’ originating from Lucille Bogan; and covered by subsequent artists such as Leroy Carr and Sonny Boy himself. Calling his version Haven’t Seen No Whiskey [Bluebird BB B7719] Joe and the boys propel this along at a fair old lick and includes a fine mandolin solo. Williams includes a variant of the verse first recorded by Ida Cox back in 1924. [Footnote 23: Although Paul Oliver has written this verse “had been in text collections long before Ida Cox” (127) made her recording.]

And the trio finish this superb side letting their instruments complete the ‘interrupted’ vocal. Consumption was a very real threat in the South (for both blacks and whites) during slavery times and into the earlier half of the 1900s. For the black communities even more so. Because of mis-appropriation of funds (from the US government) by many white-controlled state legislatures. As much as 60 % of monies earmarked for blacks was often channeled into white state treasuries. This of course led to impoverished medical care, housing, education, and daily intake of food. A major root cause for singing the Blues. Especially for black women who often provided the only steady if meager income in the family, the men often having to leave home looking for any jobs that whites did not want or otherwise allowed blacks to engage in. Even white women, as Ayers said: “… found exceedingly few opportunities to earn money in the countryside. ‘Vic is struggling to support herself. Mother and child and works very hard - cooks, works, irons. keeps the house clean and neat, sews and embroiders’ Lucy Mitchell wrote a friend in 1894, ‘but it tells on her thin and anxious face’. ‘Vic’ performed virtually all the work available to an uneducated single white woman in a farming community”. (128) But white women rarely attempted to do “all the work a farm required. It made for more sense to sell the farm and move to town, where chances for a respectable life might be found in a shop or mill”. (129) But for her black counterpart these options were rare if non-existent due to Jim Crow ‘laws’ in town or country in the South. Ayers noted: “A widowed, abandoned, or single rural black, woman, on the other hand, had probably been working ‘like a man’ for her adult life and might move into renting or sharecropping as a matter of course”. (130) The latter was little more than agricultural slavery which left the share cropper in permanent debt to the white plantation owner. The archaic-sounding Bessie Tucker who is firmly into the earliest of rural blues roots, is nevertheless accompanied on her extant recordings by an urban or vaudeville ‘pit’ pianist (in a theatre) K.D. ‘Mr. 49’ Johnson. Here ably assisted by Jesse Thomas (younger brother of Ramblin’ Thomas) on guitar. Her Mean Old Master Blues [Victor 23392] seems to concern the evil peonage system so rife in the early decades of the 1900s. In the second verse she hints at killing the ‘boss man’ to escape but resorts to a simple plea - given the powerless situation so many blacks found themselves in.

Many black women were the first of their race to move into towns and cities in the South - in great numbers - in the early 1900s. Some of these found employment as vaudeville blues singers. But often especially if abandoned by a man, would find themselves in a desperate situation and turned to heavy alcohol consumption. Esther Bigeou surely spoke for many members of her sex on her Stingaree Blues (A Downhome Blues) [OKeh 8025] in 1923. [Footnote 24: The excellent 1930 recording Stingoree Man Blues by Irene Scruggs with Blind Blake accompaniment is a different song.]

Turning to a bottle of whiskey or more likely some form of bootleg liquor, she sees the fusion of the Blues and strong liquor as inexorably dragging her down. Setting a backdrop for the late Gil Scott-Heron to immortalize in the latter decades of the 20th. Century.

Seriously heavy drinking implied by Ms.Bigeou’s phrase ‘blues in the bottle’ seems the immediate ‘solution’ for Mary H. Bradford (who also recorded as ‘Auntie Mary’ Bradford) on her Waco Texas Blues [OKeh 8123] in 1923. Her lover, presumably from Waco, has left her for good. ‘Burying’ him in her sub-conscious is not so easy or immediate (and therefore a less desirable) option as to “put ‘im down in alcohol”

In 1927, Mississippi’s Papa Harvey Hull and Long Cleve Reed (see JSP 7798-A) presented a small group of fine recordings harking back to country blues at its earlier stages. A sort of pre-blues atmosphere permeates their Hey Lawdy Mama - France Blues [Black Patti 8001].

Country blues men like Hull and Reed would have undoubtedly frequented the barrel houses in the Mississippi Delta. But as I noted earlier vaudeville blues singers generally stayed out of these places. As well as appearing in shows in theatres found in cities across the Eastern half of the US, they would often find work in cabaret establishments. One of the more famous and long enduring husband/wife teams in early blues was Coot Grant and Kid Wilson. On their fine Find Me At The Greasy Spoon [Paramount 12337] they illustrate the difference between a barrel house and a cabaret or “dancin’ room”. The implication being that the barrel house was a much more inferior or low-down and rougher place than a cabaret. Assuming the role of an irate wife who’s husband goes out every night, she phones him to give this message.

The following year, 1926, Grant (Leola B. Wilson) and Wesley ‘Kid’ Wilson recorded yet another dance which would hit the cabaret and no doubt the barrel house circuits, called Scoop It [Paramount 12379]. Part of which ran:

In 1932, Blind Willie McTell teamed up with ‘Ruby Glaze’ - almost certainly Ruth Willis - for some superb and raunchy numbers. The latter adding her sensual and erotic comments after a verse. While Grant and Wilson’s Scoop It is certainly about a new dance, the McTell item Mama, Let Me Scoop For You [Victor 23328] [Footnote 26: See Railroadin’ Some Ibid. p.26. For more on this song and the origin of ‘scoop’.] is quite obviously a mainly sexual/sensual song. To the excellent raggy accompaniment of his 12-string guitar, it is only in his opening lines the listener could be convinced the subject is dancing!

But a few moments later there is little doubt the idea of a dance has been abandoned.

The ‘barrels of ’liquor’ line having been ‘lifted’ from Salty Dog Blues (CD 3) by Papa Charlie Jackson some 8 years earlier. Blind Willie McTell probably drew on earlier vaudeville blues material more than any other singer of country blues. This included songs by Rosa Henderson and at least two by Butterbeans and Susie. He cut versions of the latter’s mega-violent A-Z Blues and Married Man’s A Fool in 1949 and 1956 respectively. Probably the most popular duo in the 1920s “Butterbeans was born as Jodie Edwards in Marietta, Georgia in 1898 and Susie Hawthorn in 1899 in Pensacola, Florida. [Baker adds] The turn of the century can also be taken as the approximate birth date of the black vaudeville circuit so vital to the development of Afro-American culture”. (141) Importantly, Duck Baker notes that Butterbean’s “sermon on ‘A Married Man’s A Fool’ is a good example of the kind of humor that passed from the vaudeville stage to country blues. So did many floating verses”. (142) Some of this often black humour (no pun intended) appears in their Bow Legged Papa [OKeh 8241] in 1925. With a warning from Susie that ‘Butter’ had better stop straying from the marital home and keep on the “straight an’ narrow path”.

[Footnote 27: This appears as a unique phrase, possibly of Susie’s own making. Although Partridge does give the following definition under one of various entries for ‘goose’. “Everything is lovely and the goose hangs high…coll[oquial]: C.19-20; ob. Ex a plucked goose hanging out of a fox’s reach”. (143) Just maybe this was not as obsolete as Partridge supposed in the early 20th. century. Roughly translated by Susie as withdrawing her ‘sexual favours’ if Butterbeans doesn’t behave. Is it a coincidence that he admits at one point that he is ‘slicker than an old sly fox’?] About 3 months later Ida Cox would put out her How Can I Miss You When I’ve Got Dead Aim [Paramount12234] with fine backing from the Lovie Austin outfit. But this phrase ultimately derives from a ‘blues ballad’ Railroad Bill’, and under this title appeared as the only commercial black recording of the piece - by Will Bennett - in the pre-war era. Although several versions exist in the Library of Congress archives and some have been released on CD. Reaching back into the end of the 19th. Century, this song was about a real-life character and a train robber called Morris Slater who was shot dead by law officers in 1897; down in Alabama. [Footnote 28: See Railroadin’ Some. Ibid. p.p.180-181 for a fuller account of Morris Slater.]

Whereas Butterbeans and Susie made dozens of recordings together, another vaudeville blues duo made only a fleeting appearance, in 1927. Although Martha Copeland was prolifically recorded she teamed up with Sidney Easton for just 2 titles. One of which was Hard Headed Mama [Victor 20548]. With Bert Howell’s sawing fiddle, Copeland gives out the most predominant persona in vaudeville blues - that of an individual not to be messed around with - especially by the opposite sex! She gives him notice to quit in no uncertain terms having made up some “new rules”.

Easton then reacts threatening violence to which Martha Copeland responds to in like fashion and delivers her opinion in withering style.

In similar vogue, Viola McCoy cut her superlative “Git” Goin’ [Cameo 1097] with a blistering solo by Louis Metcalf and a rocking piano accompaniment from Cliff Jackson, at the end of 1926. But some of these women, usually referred to in the 3rd. person by the singers, had no qualms about wrecking the life of another woman by taking her lover/husband away from her. Fairly common names were used for this fictitious character - as Clara Smith’s ‘Hannah Johnson’ and Mary Stafford’s ‘Lizzie Brown’. (CD 2) So with Lucille Hegamin, one of the main singers to swiftly follow Mamie Smith into the recording studio - only about 3 months after Smith’s Crazy Blues (CD 1). Ms. Hegamin gives the low-down on ‘Lillie Lee’.

She meets ‘Sadie Stowe’ who ‘had a beau’. Lillie Lee falls for him big-time and she says to the hapless Sadie in the song:

This was Ms. Hegamin’s biggest hit and the “song was recorded many times by blues singers and jazz bands,” (150). Her husband Bill Hegamin was probably on the piano stool. An immortal verse reflecting this aggressive and amoral (or immoral) self-assertion in early vaudeville blues singers, was long thought to have first been recorded by eerie singer/slide guitarist Sam Collins. (see JSP 7781-4 trax). Indeed, it forms part of his title Devil In The Lion’s Den [Gennett 6181] in 1927. But in recent years - so I discovered - a form of these lines were included by Sara Martin in 1923 on her Uncle Sam Blues [OKeh 8085]. A ‘harder’ bluesier vocal was supplied by Edna Hicks (once again). Her version of Uncle Sam Blues [Paramount 12069] which came out some 3 months later in early November, 1923, closely followed Sara Martin’s original recording. Interestingly, 2 other versions of this song issued between times, omitted the ‘lion’s den’ verse and only Tudie Wells (see Table 4) included the ‘warning’ to other women in respect of their men.

The first verse was adapted from an early Blind Lemon (see JSP 7706) song while the second soon became a floating verse in the country blues canon - where indeed, it may well already have been extant in the rural tradition. Table 3 [Footnote 29: Uncle Sam by the Earl Richardson Quartet in 1941, for the Library of Congress may be a fifth version. But this cannot be determined as it remains an unissued item.]

This aggressive streak in vaudeville blues singers is reflected in some of the dances they introduced on their records. Black dance is a major factor in African American culture (see p.p. 12, 22-27, 36-37). In 1926, Alberta Hunter - who is often linked with the origins of the Black Bottom - told her listeners how to do another new dance; in her good-rocking Everybody Mess Around [OKeh 8383].

[Footnote 30: A cool cat (male) based on the role in the film a Sheik of Araby played by Rudolph Valentino a few years earlier. The female equivalent (less popular in the Blues) became ‘Sheba’ from the Old Testament.] Inspired no doubt by the last line in Ms. Hunter’s 4th. verse, Atlanta’s 12-string guitar hero, Barbecue Bob, picked up on yet another dance often thought to have arrived in the 1950s - the Twist - introduced by Hank Ballard & The Midnighters; famously covered by Chubby Checker. Calling it Twistin’ Your Stuff [Columbia unissued) Bob carries his song along at a furious pace. In 1924, Trixie Smith cut a fine Don’t Shake it No More [Paramount 12211] which although does not mention the Mess Around, does include reference to other dances such as the very descriptive Shimmy-She-Wobble. Further to this, parts of Ms. Smith’s low-down melody, were taken up by the Memphis Jug Band for their ‘slow-dragging’ Fourth Street Mess Around [Victor 23251] in 1930.

Viola McCoy had recorded a version of Henderson’s How Come You Do Me Like You Do only a few months later, in 1924. But in the latter half of her recording career she cut her fine Slow Up Papa [Cameo 1144] liberally sprinkled with references to automobile parts used as telling sexual symbolism. A couple of years later, Barbecue Bob responded with Honey Your Going Too Fast [Columbia 14436] in 1929. Robert Johnson’s well-known phrase ‘keep on tanglin’ with the wires’ from his Terraplane Blues must have surely been influenced by these recordings. Especially Viola McCoy’s lines:

Rosa Henderson’s Penitentiary Bound Blues [Vocalion 14995] from 1925 is, in lyrical terms, barely one step removed from Blind Willie McTell’s Death Cell Blues [Vocalion 02577] recorded 8 years later. [Footnote 31: McTell’s Death Room Blues, which he recorded 3 times for Vocalion between 1933-1935 (all remained unisssued at the time), is a different song.] In essence they are variations of the same song. Ms. Henderson posits the scenario of a prisoner facing a (literal) life sentence whereas Blind Willie contemplates “a crap’s eye worth of freedom” (155) just before the state send his subject into eternity. The vaudeville blues of the 1920s/30s and the rural blues, which lie at the roots, are not two separate genres but inexorably inter-linked as one; which I hope this CD set more than ably demonstrates. The influence from one to the other is far more prevalent than is generally acknowledged. It is also not just a one-way traffic from country to city but much more reciprocal. Being primarily a vocal music the lyrics of the early Blues were of paramount importance to its original audience - the working-class African Americans.

‘Mississippi’ Max Haymes October, 2011. Notes:

__________________________________________________________________________ © Copyright 2012 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||