Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

I Need-A Plenty Grease In My Frying Pan |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

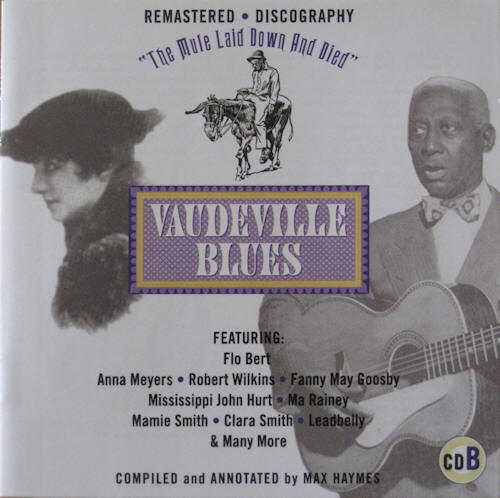

CD B - It's Papa's Elgin Movements From His Shoulders Da-Own

Along with Mamie Smith and several other singers from this earliest period prior to 1923, ‘’blues’ is mixed up with jazz as this was the era which heralded in the ‘flapper’, the ‘vamping queen’, and the dance called the Black Bottom. Railing against the white establishment, who loathed ‘that jungle music’ and often spoke out in public their burning desire to see it vanish off the face of the earth; Flo Bert would sing:

Another singer from this earliest period Julia Moody who started recording in 1922, made 16 sides; two of which have not turned up and one remains unissued. This was over a short period with her last disc being cut in 1925. A more competent singer with a slightly deeper voice than Flo Bert. As Rye comments “On these early recordings she performs well enough in the standard vaudeville-blues idiom of the variety artistes whose work made up the first blues boom.” (45). But one verse from her Good Man Sam [Paramount 12155] in 1922 is of more than passing interest. Appealing to her lover to leave his other woman “that yaller dame” and come back to her.

The other interesting note is Ms. Moody’s reference “I’m just a rollin’ stone” – among the earliest. (see Daisy Martin for the very first one - CD 3) In 1929 the title appears in the blues of the unique singer Robert Wilkins (JSP 7725-D) and of course much later by Muddy Waters. “Using a sparse, hypnotic guitar accompaniment, Wilkins … conveys a real sense of standing expectantly on the station platform waiting for the train to roll up in a cloud of hissing steam”. (48) which will take him away from the woman he loves. One of the most well-known songs in the early blues is ‘Ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do’. Recorded by such luminaries as rural blues man Frank Stokes and Bessie Smith, it is curiously more often associated with the 1947 side by Kansas City blues shouter, Jimmy Witherspoon. However, it’s first sung waxing was made in 1922 by Anna Meyers as ‘Tain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do. [Pathe Actuelle 020870] Meyers, who may well be the fine singer Hazel Meyers who recorded quite prolifically from 1923-1926, unusually adds an introduction before breaking into the familiar melody. Around 6 years later ‘pastoral’ guitarist Mississippi John Hurt cut Nobody’s Dirty Business [OKeh 8560] sans the intro -along with most other early versions of this song. However, in 1919 black ‘super star’ Bert Williams did it’s Nobody’s Business But My Own [Columbia A2750] as a monologue where he features a resume of the theme. He then ‘speaks the tune’ but with entirely different words. The song apparently goes back to the end of the 19th. Century in the West Indies where it was featured as ‘Nobody’s Business But Me Own’ as a traditional mento - related to the more famous calypso. Williams was born in 1874 “in Antigua, British West Indies”. (49) Coincidentally(?), “his family moved to the United States when he was a child, [but] he maintained a Caribbean accent until he died in New York, on 5 March 1922” ; (50) the same year Anna Meyers made her version of ‘Nobody’s Business’. Time and time again blues writers have revealed their prejudices when it comes to many recordings of vaudeville blues - especially the earlier sides. These writers seem to be either coming from a jazz or a ‘pure’ country blues perspective. But appreciation of our music goes much deeper for the blues historian looking at the socio-historical angle as well. A case in point is Martha Copeland a singer we know very little about but who made a total of 34 sides between 1923 and 1928 - all of which were issued. Many of these are finely sung blues by any standard while some are more of a socio-historical importance. Indeed, this is true for the original working-class black audience in the South in the 1920s and ‘30s; at whom the blues record was marketed. This reason for purchase was of paramount importance. This is why the legendary Robert Johnson ‘bombed’ (in US parlance) on all but one of his 29 sides - the exception being his Terraplane Blues [ARC 7-03-56] . A not too dissimilar number to Copeland’s output, but Johnson’s figure included three that never saw the light of day until the initial Blues ‘boom’ in the 1960s. Sadly, the comment by one writer that Martha Copeland’s “four sides for Victor are rather dull vaudeville-style performances” (51) is not as rare as one might have hoped; in today’s world of the Blues. Although Martha Copeland appeared in The Guinness Who’s Who Of Blues, their brief entry does not include any biographical details. They do however, give a more ‘enlightened’ assessment of her singing qualities. “Copeland was one of the legion of second-string female blues singers of the ‘classic’ period … and demonstrated a good ‘moaning’ style on occasion with considerable humour. Despite some promotion by Columbia who billed her as ‘everybody’s mama’ [sic] she never achieved the popularity of stable mates Bessie and Clara Smith”. (52) The writer is being a little disingenuous here, as both the Smith girls were the most popular and best-selling blues singers on Columbia. Therefore it follows that all the rest on this major label also “never achieved [their] popularity”! In 2006 Chris Smith introduced the entry for Martha Copeland in an essential Blues Guide with these words: “Billed by Columbia as ‘everybody’s mammy’, Copeland was popular in her day, but attempts to research her life have drawn a blank”. (53) This makes her recorded legacy all the more important as her only legacy; both historically and musically. On her The Penetrating Blues [OKeh 8091] she includes a verse, which later became part of several versions of a blues by inimitable rural singer, Blind Willie McTell. (see JSP 7711) With a sense of drama and a sometimes halting vocal, Martha Copeland lays down some background to her blues; while Eddie Heywood includes a rare snippet of early boogie piano at one point, in 1923!

The singer’s graphic imagery using the sewing needle could well point to an alternative occupation to her musical career - that of a seamstress, one of the most preferred jobs open to black women in the 1920s as well as being by far the better paid. As in the previous decades by 1910, for black women in Chicago “almost all of the Negro women classified under the manufacturing trades were dressmakers, seamstresses, and milliners working in their own homes”. (55) Even by 1920 when “ … over three thousand Negro women - 15 per cent of the female labor force - were unskilled and semiskilled factory operatives”. (56) there were still African American women working at 1,070 jobs in the dressmaker and seamstress industry. This represented 12.6% of the total female black workforce in the Windy City. (57) Although I don’t have figures available for comparable percentages in the main Southern cities of Memphis, Atlanta. Birmingham, etc. there would have been openings for a black seamstress in the earlier 20th. Century. In any case thousands of women traveled northward - in the great migration -between the World Wars, and Chicago was the major stopping place. Perhaps Martha Copeland was one of them. But some three months prior to the Copeland recording, Fanny May Goosby was the first artist to put on wax the basis of the McTell song. With a much ‘harder’ vocal approach she defined exactly which engine she was talking about. Grievous Blues [OKeh 8079] was sung in a lower register than she usually employed, in mid-June, 1923, and accompanied by some nice chiming piano (possibly the singer’s) and a joyful bit of double-time with the unidentified cornet player in the break.

Goosby was to remake this, (as a response?) sans the piano solo and double-time passage about ten days after the Copeland version came out. Now, it happened that Fanny May Goosby supplied the other side to the first field recording in 1923 which featured Lucille Bogan’s Pawn Shop Blues as already noted. This was down in Atlanta, Georgia, where the great Blind Willie McTell had made a temporary base along with a lot of other blues singers, prior to his debut for Victor Records in 1927. He may have even heard her in person as she was described in a quote used by David Evans from the ‘Chicago Defender’ “as ‘a clever little composer and singer from Atlanta’ and noting that she was ‘very young’. What she did for the next five years is unknown, but one assumes she stayed close to Atlanta and worked the vaudeville theatres there”. (59) In any event, in 1931 McTell cut his truly classic Broke Down Engine Blues [Columbia14632-D] which greatly extended the symbolism of Goosby’s lone verse.

Blind Willie McTell was to record three more versions of Broke Down Engine in a 1933 session. As too, would his fellow Georgia guitarist, the younger Buddy Moss, in the same year. (a mini-article in the making?). A far more grim a subject is involved with the next song up for consideration, by Leona Williams - Bud Russell. But first a little more preamble on the differing ‘shades’ of vaudeville blues and some collectors’ attitudes to them. Steve Tracy observed that “the popular fallout from the success of Mamie Smith’s recordings for OKeh caused New York companies to rush in search of performers who would fill the demand for recordings in this new vaudeville blues idiom. As is often characteristic of music in the pop market, tunesmiths were at work sanding away the ‘rough edges’ of the source material and adding a lustrous polish in order to make the material more acceptable to a broader buying public, leaving it until 1923 and the recordings of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey to bring the original down home deep blues force and directness stylistically and thematically to the vaudeville blues recording industry”. (61) This reflects back to David Evans’ comments about the Flo Bert title that opens CD 2. In 1920, the aim of these recording companies was the general market (both white and black). Although by 1923 the other leading labels had followed OKeh’s 8000 series Race Records example. This year resulted in the much heavier blues of Smith and Rainey, and co. to appear on wax. While I agree with Steve regarding the rural or ‘down home deep blues’ and its ‘directness stylistically’, I do take issue with his phrase ‘and thematically’. This is part of his introduction to the complete recorded works of Leona Williams from 1922-1923. He refers to pioneer singers such as Leona, Mamie Smith and Lucille Hegamin as representing “the primary strain of recorded blues”. (62) This is true, but one of Leona Williams’ songs is the first on a record to use the title ‘Uncle Bud Russell’ - the notorious ‘transfer man’ in Texas. In 1939, after Alan Lomax interviewed a very eloquent black ex-prisoner, Doc Reese; who had just served a short sentence in the Central State (Prison) Farm at Sugar Land-down in the Brazos Bottoms - Reese gives an account of Bud Russell. “Now you must know that in red-heifer times [Footnote 15: “Reese, as a result of youthful escapades, had served a sentence in the Texas pen during ‘red-heifer times’, so-called because the lash that drove prisoners was made of red-heifer hide with the hair still on it”. (The Land Where The Blues Began. p.287. See bibliography.] a man by the name of Bud Russell operated the transfer wagon that collected the prisoners from all over the state and brought them to the pen. They called him Uncle Bud and they sung many songs about him.

The [black] prisoners used to sing that song to Uncle Bud’s face. They sang a different song behind his back.

So ever after on, they call any man that operates the wagon “Uncle Bud’, no matter what his name is. In place of Black Maria, we call Uncle Bud’s old wagon Black Betty”. (63) Leona Williams may have been one of Tracy’s singers who’s ‘rough edges’ had been sanded down and given a ‘lustrous polish’ but her verses which had no option other than to be those she could sing to Uncle Bud’s face are the first we know of on a blues recording.

Thematically Leona Williams could not have got closer to the source material (being a ‘standard’ prison song in the South). This of course is not a lone example. The very raison d’etre of this JSP set is to explore and highlight the thematic and lyrical links between vaudeville and rural blues, and I still have enough vaudeville titles - including more from Williams - to fill a Volume 2 and probably a third set, too! Incidentally, this Williams side is part of an early integrated recording session as she is accompanied by the white Original Memphis Five as “Her Dixie Band” which included Phil Napoleon on cornet (and Jimmy Durante on piano on another session in the same year.). Despite the CD notes dismissal, the band acquit themselves well. But as Steve rightly says “… the folk rhyme-inspired ‘Uncle Bud’, [was] also recorded in similar form by Tampa Red,”. (65) The latter was made in 1929 as Uncle Bud (Dog-gone Him) [Vocalion 1268]. Although Tampa Red uses more varied lyrics and is much more up front in addressing ‘Uncle Bud’, even he does not include the Doc Reese verses. The whole theme revolves around the white man taking/stealing his ‘jelly’ (lover). In the break Georgia Tom takes the role of a white man over-hearing Tampa Red’s comments

It would be fascinating to hear the three unissued (presumably now lost) takes by the duo at their previous session on 11th. December, 1928. It would seem significant that so many attempts were made on this song which I’m inclined to think did include the Doc Reese lyrics – and more besides?? In any event, in 1935 Rochelle French, for the Library of Congress, did an Uncle Bud [366-A-LS] to his own guitar accompaniment and in much the same format as Leona Williams and Tampa Red. Indeed, these were the only three versions cut in the pre-war period. French sings the first line quoted by Reese and then successfully masks the answering line - the ‘behind Uncle Bud’s back’ verse - while omitting Reese’s second verse altogether. But French, who was recorded in Eatonville, Florida, [Footnote 16: See more on Bud Russell the ‘long chain man’, his chains, and Nashville Stonewall Blues by Robert Wilkins in Blues Fell This Morning by Paul Oliver p..200 and in The Life And Legend Of Leadbelly: Charles Wolfe & Kip Lornell. p.79.] still felt he had to apologize at the end of his performance; as Rye surmises there were “ladies present or because there are white folks present”. (67) Although actual titles including the name Bud Russell are scarce (perhaps not surprisingly) there are references in several blues including a unique spoken introduction to Penitentiary Moan Blues [OKeh 8640] by Texas Alexander in 1927. With his measured words and dark moaning laced with Lonnie Johnson’s bitter sweet guitar, the full grimness of the subject matter comes home to the listener.

Such are the dark and bloody roots of the fairly mild verses as sung by Leona Williams. Some of the links discussed so far between the influences of vaudeville and rural blues must remain in the balance as to which came first. But in the case of the Bud Russell songs/verses they can inevitably be traced back to the world of black prisoners. This part of the blues roots genre really only evolved after the Civil War ended in 1865. Simply because, generally speaking, the vast majority of the black population was in bondage - they were life-long slaves. Even the tiny percentage of freedmen and women could be (and sometimes were) re-enslaved for the most spurious reasons. The concept of a state penitentiary was not a pressing factor in the mind’s eye of the ruling white classes at that time; apart from the local jails in the small towns scattered across the South. In any case, the earliest vaudeville blues singers would rarely if ever step into a barrelhouse much less pay a visit to a prison farm such as the one in Sugar Land, Texas; the subject of Texas Alexander’s blues. It is of interest to note that besides the infamous Bud Russell there was an earlier precedent in the Lone Star state, in the person of J.B. Cunningham who “was a transfer agent for the Texas prison system for a short time around 1910” ; (69) Jackson adds: “It is slightly possible … [there was] an even older referent: an A.J. Cunningham [who] was the first man to lease convicts from the Texas prison system in the early 1870s”. (70) Indeed, (J.B.) Cunningham appears in the well recorded prison song Go Down Old Hannah [matrix 199 A2] for the L. of C. in 1933 when it was recorded by Ernest Williams, James ‘Iron Head’ Baker, and a group of unidentified convicts; as well as on a commercial record Don’t Ease Me In [Vocalion 1197] in 1928 by Henry Thomas. His remake Don’t Leave Me Here [Vocalion 1443] in 1929 replaces ‘Cunningham’ with ‘sweet mama/papa’. The dark shadow of the prison’s black work gangs and their songs helped spawn another vaudeville blues number. This was Kansas City Man Blues [OKeh 4926] by Mamie Smith in 1923. Her voice has really deepened since 1920 and on one of her finest vocals, the backing group are the Harlem Trio which included stunning soprano sax from Sidney Bechet.

Within 2 months there appeared the other four versions we have on a record, albeit one remains unissued. (see Table 2) Table 2

Edna Hicks closely follows the slightly altered wording of the Josie Miles disc except in the repeated line of the last verse, where Ms. Miles sings:

As did Mamie Smith, Edna Hicks also omits ‘murder’. However, following her first attempt 3 days after the Josie Miles cut with Stanley Miller on piano, which Columbia did not issue; Clara Smith recorded a second version of Kansas City Man Blues which did include ‘murder’, in her low down moaning style where even by leaving out the opening verse rivals the duration of the original version by Mamie Smith! Both of the Smith recordings are around 25 seconds longer than the others in Table 2. This is because as John Vanco said in his comments on Clara’s early style generally and Fletcher Henderson ‘s playing in particular: “the piano’s mellow rhythm and the sparse arrangement allowed her to stretch her notes and really show off her immense vocal capacity. Due in part to the big voice that was needed to compensate for her weak accompaniment, Smith was billed as ‘The World’s Champion Moaner’ and ‘Queen of the Moaners’.” ( 73) The comment on Henderson’s ‘weak accompaniment’ is a little misplaced at least as far as Clara Smith’s recordings were concerned. [Footnote 17: Although on Bessie Smith’s earlier sides, Fletcher Henderson seems almost ‘cowed’ by the awesome presence of the ‘Empress of the Blues’ in the studio and maybe Vanco’s comment is more applicable. Another area of research] His minimalist piano sounds are full of foreboding and along with Ms. Smith’s low-down, stretched-out vocals are a direct pointer to another side from Texas Alexander: Levee Camp Moan Blues [OKeh 8498] in 1927. Some of the arduous tasks done by black prison gangs were often reflected in the work of the skinner or one who drives mules with a whip; or mule skinner. The best ones prided themselves on being able to ‘write’ their initials on a mule’s behind if it was proving troublesome or balky. As the legendary Leadbelly said on one of several recordings of I’m All Out And Down [LC unissued] 8 years later for the Library of Congress.

“From one-mule farms in the hill country to Delta plantations with hundreds of teams, the mule for over a century was the prime energy factor in Mississippi agriculture”. (75) This was the general picture throughout the South until the 1950s. This prodigious animal was used for every thing from hauling produce, supplying the steamboats at the levees, giving leisure rides to children and providing black farmers with transport to towns, as late as the 1930s. As Bill Ferris says: “In every period the role of the mule and the black man are intimately linked. As slaves before the Civil War and as tenant farmers, blacks worked the mules and were essential to the southern economy. In 1925, for example, 84 percent of the mule farmers in the Mississippi Valley were black”. (76) Not only the black men but the women, too. However. it is very rare to have a female singer - especially a vaudeville blues singer - include what became quite a floating verse in rural blues. Edna Winston’s use of this verse in her I Got A Mule To Ride [Victor 20407] may be almost unique, at least on a record.

Ms. Winston’s words cropped up (with some variation) in the blues of singers across the South, including Big Joe Williams, Sonny Boy Williamson, and Kokomo Arnold; from Mississippi, Tennessee, and Georgia, respectively. Kokomo Arnold made his The Mule Laid Down And Died [Decca 7198] in 1935, using the vaudeville blues singer’s closing lines as central to his main theme.

Towards the end of her recording career, Clara Smith also cut a song about a mule, in 1931. Although heavily-laden with double-entendre phrases, this was missed by Vanco on her For Sale (Hannah Johnson’s Jack Ass) [Columbia 14633]

To be sure, she introduces her subject who was “a red-hot stepper” as yet another victim of the Great Depression. She doesn’t mind losing her cows, pigs, or chickens but desperately wants to hang on to her ‘jack ass’ - otherwise a male mule. It’s interesting that an urban singer such as Clara Smith includes far more references to the importance of the mule in a rural setting than a country blues artist such as Kokomo Arnold. Possibly harking back to her beginnings in Spartanburg, South Carolina, before embarking on her singing career as a young teenager. Bertha ‘Chippie’ Hill, like Clara Smith was from South Carolina and also introduced a verse picked up by a Georgia rural singer. Born in Charleston in 1905 - some 10 years younger - she recorded a Low Land Blues [ OKeh 8273] in 1925. Although she doesn’t sing the title the first verse establishes just where she is coming from - in the guise of a low-down blues singer.

Ms. Hill continues in the same vein:

This second verse reappears in Charley Lincoln’s first side to be recorded Jealous Hearted Blues [Columbia 14305].

This was a direct cover of a Ma Rainey song she made in 1924 and was also called Jealous Hearted Blues [Paramount 12252]. But she did not include the above verse, so it may be safe to assume it came from Bertha ‘Chippie’ Hill. Or she picked it up from an unrecorded rural singer. But in the earliest period of recorded vaudeville blues, as we have seen, many contained up-tempo jazzy accompaniments and some were quite ‘jolly’. This was especially so on titles which eulogized a new dance. Several singers advocated the Strut, Black Bottom, and the Wicked Fives. Pre-empting dance crazes of latter day R ‘n B/Rock ‘n Roll in the 50s and 60s by some 35 years - such as the Hucklebuck, Hully Gully, or the Twist. In 1922, Lena Wilson describes dance movements well-known to the black audience in her The Wicked Fives Blues [Black Swan 1429] rocked along with some low-down sounds from an unknown group called the Jazz Masters which might include Fletcher Henderson.

And then she gives out some dance instructions:

While Mary Stafford relates how all “the belles an’ beaus stand on their toes” to see Lizzie Brown strut her stuff on her fine version of Strut Miss Lizzie [Columbia A3418] as “they all yell”:

Cora Lee, Lizzie Brown, and countless other young black women would parade and strut their stuff at the balls and cabarets in the cities. Known by the trendy name at the time as ‘vampires’, ‘vamping queens’ or ‘vamping browns’, they were a constant temptation or hazard to the equally young ‘beaus’. But older men - and especially married men - were prone to fall for the vamp’s charms, too. In 1924, Whistler And His Jug Band cut The Vampire Woman as a semi-serious warning to married men but remains an unissued Gennett item. But in 1927 and past the peak of popularity for vaudeville blues, the group remade it as Vamps Of “28”[OKeh 8469]. With deep grunting jug, and a whining fiddle, they hand out some good advice.

__________________________________________________________________________ Notes:

__________________________________________________________________________ © Copyright 2012 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||