Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

The Blues and Jazz Poetry of Langston

Hughes |

|

Part 3 Another reason for Langston Hughes employing blues music in his poetry is because the ‘New Poetry’ movement working at the same time shared many similarities with the Harlem Renaissance poets and also with a group of poets called the Imagists which included Ezra Pound. The ‘New Poetry’ movement sought to humanize poetry by using fresher and more original language, while the Imagists in particular “sought to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not the metronome” (Tracy 219). Langston Hughes had been influenced by this movement that included music in its writing format. Vachel Lindsay, a poet of the Chicago Renaissance, was also very important in setting a poetic precedent for Hughes. He used music and dramatic performance to revive poetry within a Chicago movement that drew from Walt Whitman, a poet who sought to unshackle poetry from the iambic pentameter and who showed an interest in the common man in his poetry. The times were exactly right for him to use the blues. The next poem I’ve chosen is written in what might be called a ‘Country Blues’ style.

Bound No’th Blues Goin’

down the road, Lawd, We see here that this poem portrays the lonely journey from the laborious struggle of the South to the relatively affluent North by an African American searching for a better life, as sung by a blues singer. It’s a long, lonely road, he’s saying. All you need is someone to talk to on the way and to help bear the load. He’s also wary or superstitious about his friends who may do him harm. Superstition also comes up as a theme in Hughes’s Bad Luck Card, Gal’s Cry, For a Dying Lover and Blues on a Box. Blues on a Box

Play your guitar, boy,

Moving up the Mississippi river from the southern states, many blues and jazz musicians ended up in Chicago. The Blues went electric in Chicago, with a lot of people attributing that fact to McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters after he moved from Dockery’s Plantation in the Delta state of Mississippi. Langston Hughes recognised that fact and wrote several poems for and about Chicago. Here’s one of my favourites. Chicago Blues (moral: go slow) Chicago is a

town I got in

town on Monday Thursday

morning Friday

riding Saturday I

said, Baby, Sunday I was

living Chicago is a

town Here we experience the country

boy’s wide-eyed introduction into the big city and its big city ways. This must

have been a common occurrence with the many new arrivals from the South until

they eventually settled in with their friends and relatives. Chicago was also a

very important meat processing centre and many jazz and blues musicians worked

in that industry. Howling Wolf (real name Chester Arthur Burnett) worked in that

industry on the ‘Killing Floor’ where the animals were slaughtered and later,

after signing to Chess Records, he gave that name to a song he wrote and

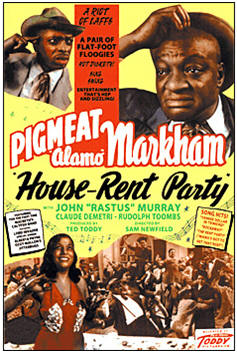

recorded. Langston Hughes met Charlotte Mason in 1927, a wealthy aged widow who became his patron for the next three years. In the summer, Hughes visited the South and travelled there for some time with Zora Neale Hurston, who is also taken up by Mrs Mason. Urged on by his patron (who insisted on being known as ‘Godmother’), Hughes completed his first novel in 1929. Funded by Mrs Mason, he visited Cuba and met many writers and artists there. His blues poems influence one poet, Nicolás Guillén, to write Motivos de Son, which were lauded as the first ‘Negro’ poetry in Cuba. In his writings on all aspects of Black America, Langston Hughes left no stone unturned in his portrayal of their culture. Rent parties were a hugely popular way of socialising while at the same time raising the money to pay the landlord –hence the name. Here’s one from Hughes on the subject. Rent-Party Shout: For a Lady Dancer

Whip it to a jelly! In this poem Hughes touches on the constant dangers of these rent parties, where loud, hot music gets the attendees dancing, all stoked up with strong drink and probably drugs too. And with that perennial combination of ingredients, the inevitable always happens. Jealousies, rage and fights break out and sometimes even murder. The social conditions in which the black community lived gave birth to a structure in which all women had a protector, and not necessarily a husband or boyfriend. But whoever the protector was, he went under the name of ‘Daddy’. It survives to this day in the soubriquet of ‘Sugar Daddy’. Here’s another Harlem period poem from Hughes, again told from the woman’s point of view. Hard Daddy

I went to ma daddy,

I cried on his shoulder but

I wish I had wings to We can see here and pretty much feel the emotional response evoked by this woman’s ‘Hard Daddy’. This kind of scenario must have been a familiar sight in black communities throughout the country. One of the basic themes in the Blues and Langston Hughes has used the classic 12 bar format with the two repeated lines and a third line reprise to tell us an emotional drama.

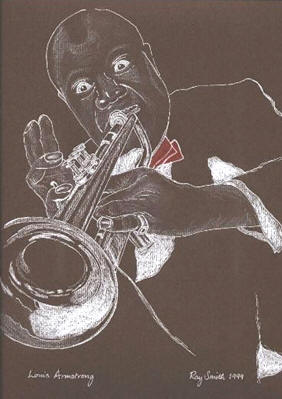

Here’s a wonderful Langston Hughes poem about a trumpet player in a typical Harlem club of the time. Trumpet Player

The Negro

The Negro

The music

Desire

The Negro

But softly In this

piece of word magic, Langston Hughes touches on the very being of a jazz and

blues musician of the time. Jazz and blues music was developed on a set of

chords or riffs of an original tune and these became the building blocks for the

musicians. The best of the best were the ones who could endlessly improvise over

a set of chords of the tune. The trumpet player portrayed here by Hughes is lost

within the music that he makes and transcends the present to play, quite

literally, the ‘music of the gods’. Langston Hughes translated the music, art, language and life of the black community as being the very life blood and soul of his beloved Harlem. He revelled in the night life and was continually inspired to write. Here are two examples from that club scene he loved so much.

Juke Box Love Song

I could take the Harlem night Easy Boogie

Dance in the bass

Down in the bass Riffs, smears, breaks.

Hey, Lawdy, Mama! We see here in the first example the narrator wishing he could wrap all the colourful sights and sounds of Harlem around his girl, transfer them to a record on the juke box and then lose them both in their own very special dance. In other words, he wants them both to live and breathe and be the very essence of this night time Harlem he evokes so well. The second poem celebrates the work and music of the bass player. Often overlooked in favour of the front men with their showmanship and prowess on their chosen instrument, nevertheless the bass player along with the drummer and banjo or guitar player, were the essential engine room of every band. They were known as the rhythm section and indeed their job was to hold down that rhythm and keep the correct time signature. Hughes sees this in the first stanza with his ‘ steady beat, walking walking walking, like marching feet.’ In the second stanza he starts to feel the bass getting right inside him ‘rolling like I like it, in my soul’, then in the third and last stanza he makes a sexual innuendo with the rolling bass.

Ray Smith |

|

Return to Blues Poetry -

Introduction |