Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

The Blues and Jazz Poetry of Langston

Hughes |

|

Part 4 In 1930, funded by Mrs Mason, Langston Hughes went to Cuba and met many writers and artists there. His blues poems influenced one poet, Nicolás Guillén, to write ‘Motivos de Son’ (1930), hailed as the first ‘Negro’ poems in Cuba. Here are two poems from that period.

Black Dancers

We Hughes has touched here upon the everlasting soul and dilemma of the professional entertainer. Whatever personal tragedy may have occurred in their life, the show must go on with a smile and a professional performance. Only backstage when the show is over will that sorrow be finally shown. Havana Dreams

The dream is a

cocktail at Sloppy Joe’s –

The dream is the

road to Batabano.

Perhaps the dream

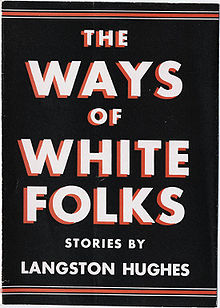

is only her face – Langston Hughes choice of words in this dream poem is tremendously lyrical. They flow just as much as the dream he’s describing and fit to perfection the images he creates. Also in 1930, Langston Hughes’s first novel, Not Without Laughter, won the Harmon Gold Medal for literature. The protagonist of the story is a boy named Sandy whose family must deal with a variety of struggles imposed upon them due to their race and class in society in addition to relating to one another. Hughes’s first collection of short stories came in 1934 with The Ways of White Folks. These stories provided a series of vignettes revealing the humorous and tragic interactions between whites and blacks. Overall, these stories are marked by a general pessimism about race relations, as well as a sardonic realism.

Following the death of his father, Hughes travelled to Mexico late in 1934. He stayed for six months translating short stories by various young Mexican writers, as well as continually writing himself. This is one from that time. Mexican Market Woman

This

ancient hag This is a fine piece of observational writing that tells a story in just seven short lines and creates wonderful sun-baked images. By 1936, Hughes was back in New York after his play ‘Mulatto’ opened on Broadway. He continued to travel around the country, basing his poetry and stories on observations as he went.

Share-Croppers

Just a

herd of Negroes

When the

cotton’s picked

Leaves us

hungry, ragged

Than a

herd of Negroes

Hughes in this poem

highlights the lot of the black share-croppers but many poor white families were

involved in this trade too. It was a widespread practice throughout the southern

states of America and he describes it perfectly. Langston Hughes travelled to Europe in 1937 to cover the Spanish Civil War for the Baltimore ‘Afro-American’ and other black newspapers. He addressed the Writers’ Congress in Paris, representing the League of American Writers and was later trapped for three months in the besieged city of Madrid. He returned to the U.S. early in 1938 and founded the Harlem Suitcase Theatre whose first production was his play ‘Don’t You Want To Be Free?’ which ran for thirty-eight performances. Here’s one of the longest poems by Langston Hughes, written back in his beloved Harlem.

Death in Harlem

Arabella Johnson

and the Texas Kid

At a big piano a

little dark girl

Dancin close, and

dancin sweet

Folks at the

tables drink and grin.

Now, Texas was a

lover.

Arabella drew her

pistol.

Oh, they nabbed

Arabella

Hughes here describes a

typical Harlem nightclub scene with frightening accuracy, possibly from

witnessing something similar at first hand. There were certainly gangsters

involved in the club scene, both black and white, and similar acts of violence

must have been almost a nightly occurrence. Hughes also describes a party of

affluent white people visiting the club to ‘get a view’ and portrays a ‘tall

white woman in an ermine cape’ displaying the stereotypical prejudices that were

common at that time. And all through the story Miss Lucy is exhorted to pound

out the music on the piano until finally when dawn breaks after all the mess,

the Texas Kid ‘with lovin in his head’, cynically ‘picked up another woman . . .

and went to bed.’ In 1939 Hughes went to Los Angeles and together with actor-singer Clarence Muse, wrote the script of the motion picture Way Down South, a vehicle for the boy singer Bobby Breen. The film had lots of musicians both black and white but to his dismay, progressive critics accuse Hughes of selling out to Hollywood. However, he manages to clear various debts and to work on his autobiography as well as his poetry.

Hey-Hey Blues

I can HEY

on water

If you

can whip de blues, boy

While you

play ‘em,

Cause I

can HEY on water, Yee-ee-e-who-ooo-oo-o! Hughes here has the singer praising the effect that good corn whisky has on his vocal chords while acknowledging the ‘perfesser’ as a talented musician. The same effect works with today’s alcohol and pub singers! Here’s another poem by Langston Hughes that makes an analogy between a train’s motion and making love. Six-Bits Blues

Gimme six-bits’

worth o’ ticket

Baby, gimme a

little lovin’

I got to roll

along! And in this next poem, Hughes laments the mixed emotions that love can bring. Love Again Blues

My life ain’t

nothin’

When I got you I

Tell me, tell me, In 1940, Hughes spent several months in Chicago working on a musical review for the Negro exposition but was poorly paid and his scripts ignored. His autobiography, The Big Sea, is published to mixed reviews and is in three sections that take him from his childhood to the age of twenty-nine.

After two years spent mainly

in California, Langston Hughes returned to New York. On behalf of the war

effort, He worked on various projects for the Office of Civil Defence and,

later, the Writers’ War Committee. He devoted much of his time to writing song

lyrics but also wrote ‘Stalingrad: 1942,’ a militant poem inspired by the Soviet

defence of the besieged city. In November of that year, Hughes started a weekly

column ‘Here to Yonder’ in the Chicago Defender newspaper. Here’s two poems on one of the eternal Blues themes of love and women. In a Troubled Key

Do not

sell me out, baby,

Still I

can’t help lovin’ you, In this first example, Hughes has crafted a classic 12 bar blues on the doubt that’s creeping into the narrator’s mind after he can’t help loving her ‘even though you do me wrong.’ The doubt turns into a threat in the second verse with the last two lines of the stanza and, although said in a friendly way, the threat of the knife is still there. This would be a great slow acoustic slide guitar number and I’ve already tried it out myself with a tune I’ve put to these words. Only Woman Blues

I want to

tell you ‘bout that woman,

She could

make me holler like a sissie,

She had

long black hair,

I got het

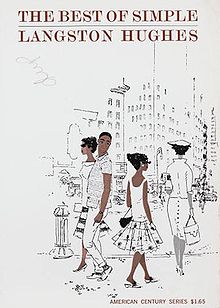

in Mississippi. In this second example, the narrator describes his ‘used-to-be’ and bemoans his fate at the things she did to mistreat him so. Although he is in praise of her long, black hair and big black eyes with a ‘Glory! Hallelujah!’, by the last verse he’s glad to see the back of her when she leaves him, saying (and you can imagine this with a grateful sigh): ‘Go, hot damn! You de last and only Woman’s gonna mistreat me.’ Through the black publication Chicago Defender, Hughes in 1943 created Jesse B. Semple, often referred to and spelled Simple. This character was based on many conversations in a Harlem bar with a man he knew, and My Simple Minded Friend became a series of essays in the form of a dialogue throughout the 1940s. (In 1950, he authored a series of books on him).

Here’s a poem touching on two more of the classic Blues themes of drinking and the supernatural. Crowing Hen Blues

I was sitting on

the hen-house steps

I had a cat I

called him

I said to baby,

Ummmm-mmm-m-huh! I

wish that Maybe the supernatural element in this poem is due to the narrator’s drinking! It’s certainly an explanation for his black cat having ‘riz up and . . . Started talking like a man.’ His woman certainly couldn’t here anything apart from his own drunken snoring, because he then makes the decision to carry on drinking where he is on the hen-house steps and telling his woman to move if she doesn’t like it! As a musician, this poem puts me in mind of Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Little Red Rooster’ and, in fact, can be sung to the very same tune. There’s no evidence of plagiarism on anybody’s part and, as so often happens with blues lyrics, coincidence plays a very large part due to the limitations yet the diversity of the 12 bar format. Ray Smith Part 5 coming soon |

|

Return to Blues Poetry -

Introduction |