Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

The Blues and Jazz Poetry of Langston

Hughes |

|

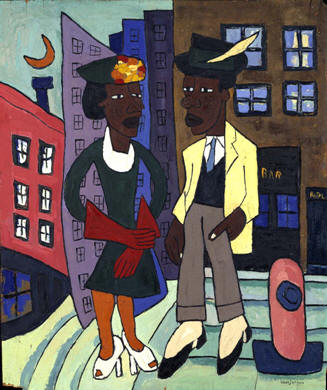

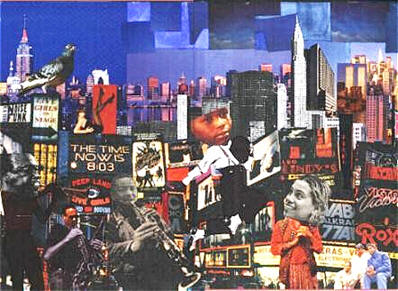

Part 2 Langston Hughes received a scholarship to Lincoln University, in Pennsylvania, where he gained a BA degree in 1929. In his writings from the 1930s, Hughes was unashamedly black when blackness was most definitely out of favour and he didn’t stray far from the themes of ‘black is beautiful’ as he explored the black human condition in a variety of depths. His main concern was the uplift of his people, of whom he judged himself an adequate appreciator, and whose strengths, resilience, courage and humour he wanted to record as part of the American experience. Thus, his poetry and fiction generally dealt with insightful views of the working class lives of blacks in America, lives he portrayed as full of struggle, joy, laughter and music. Here’s another example from The Weary Blues collection.  Night Time in Harlem Paper collage & watercolour artwork by Ray Smith 1997 Harlem Night Club

Sleek black boys in a

cabaret. This poem portrays Hughes’s Harlem as a place bursting with vitality and full of life. Everything revolves around the blues and jazz clubs and all the rest of the hectic nightlife, as can be seen in the poem where everyone, no matter what the colour of their skin, is enjoying themselves. Nevertheless, not everything looks bright as the last two lines at the end of the poem remind us about the coming reality of tomorrow. Langston Hughes stressed the importance of a racial consciousness and cultural nationalism devoid of self-hate that would unite people of African descent and Africa across the globe and encourage pride in their own diverse black folk culture and black aesthetic. He was one of the few black writers of any consequence to champion racial consciousness as a source of inspiration for black artists. Hughes was not only a role model with his calls for black racial pride instead of assimilation, but the most important technical influence in his emphasis on folk and jazz rhythms as the basis of his poetry of racial pride, struggle, joy, laughter, and music. A constant theme throughout his work is pride in the African American identity and its diverse culture.

Hughes is quoted as saying, “My seeking has been to explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America and obliquely that of all human kind.” Therefore, in his work he confronted racial stereotypes, protested social conditions and expanded African America’s image of itself; a ‘people’s poet’ who sought to re-educate both audience and artist by lifting the theory of the black artistic culture into reality. Here’s a blues poem from his Harlem period.

Blues Fantasy

Hey! Hey! The train is an important image and theme in the blues and it’s usually taking a lover away, bringing a lover back, going back home, or escaping constant oppression. Here, Hughes has expressed sorrow in the loss of a lover yet a glimpse of hope shines through with ‘I’ll cast my blues aside’ and then joy in the last stanza. Another poem of Hughes’s that has this same imagery is ‘Dream Boogie: Variation.’ Dream Boogie: Variation

Tinkling treble, Here Hughes is making a wonderful analogy between the music made by the blues pianist and the ‘music’ that a steam train engine makes. The relationships between the men and women he encountered in Harlem also provided Hughes with a rich vein of human emotion and experience within which he wove his jazz and blues poems to good effect. These poems portray eternal scenes of love, betrayal, social upheaval and discrimination, together with alcohol, drugs, violence and even murder, all set against a background of pulsing jazz and blues music. Here’s an early Langston Hughes poem on these themes.

Workin’ Man

I works

all day

I calls

for my woman

I does

her good

I’m a

hard workin’ man Written in the first person, Hughes’s alter ego laments the life he is now living in a ‘hovel’, betrayed by his woman who he suspects of walking the streets as a prostitute. He ‘treats her fine’ but she doesn’t give him any warmth or love even though he works hard until he eventually ends up ‘payin’ double’ by trying to lead a good life but suffering the consequences of his own and his woman’s actions. Here’s another example, with this poem showing the much darker side of Hughes’s beloved Harlem. Death of Do Dirty

O, you

can’t find a buddy He was a friend of mine.

They

called him Do Dirty Ma friend o’ mine.

But when

I was hungry, Good friend o’ mine.

An’ when

de cops got me O, friend o’ mine.

That

night he got kilt Ma friend o’ mine.

But when

I got there Best friend o’ mine.

An’ de

ones that kilt him, - Ma friend o’ mine. In this poem we can see that Langston Hughes has placed the deep bond of a valued friendship transcending any other action or virtue. Powerful emotions have been stirred and vengeance sworn in the last stanza as he cries out ‘damn their souls.’

It was the music and its consequences in Harlem that still inspired Langston Hughes the most. This next poem is a heart-rending blues that wouldn’t have sounded out of place accompanied by a jazz or blues band back then or even today. In those Harlem days, all the jazz bands played blues and the blues musicians often doubled as jazz players to earn more money. Young Gal’s Blues

I’m gonna

walk to the graveyard

The po’

house is lonely

When love

is gone what This poem reminds me very much of those blues ballads sung by the great Bessie Smith and that’s how I hear it as I read. Bessie too was able to wring every ounce of emotion, pathos and even anger out of her blues. In this example, the young gal in Hughes’s poem bemoans her own future fate in the funeral procession of her friend, Miss Cora Lee and in the inescapable fact of growing ugly and old like her Aunt Clew, while attempting to prevent losing her daddy’s love because she doesn’t want to be blue. Ray Smith |

|

Return to Blues Poetry -

Introduction |