Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

The Blues and Jazz Poetry of Langston

Hughes |

|

Part 1 James Mercer Langston Hughes was born on February 1st 1902 in Joplin Missouri. He was the great-great-grandson of Charles Henry Langston, whose brother John Mercer Langston was the first Black American to be elected to public office. His parents divorced while he was still a small child and his mother took him to Lawrence, Kansas, where she’d grown up, while his father moved to Cuba and then Mexico. Langston and his mother start living in a state of poverty at the home of her mother, Mary Langston. In 1907, following an attempted reconciliation in Mexico, Langston and his mother return to Lawrence. In the frequent absence of his mother, who was constantly moving around looking for work, he was raised by his grandmother until he was thirteen, when he moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her new husband. The family eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio, but it was in Lincoln that he started to write poetry. After graduation from Cleveland’s Central High School, he spent a year in Mexico with his father and a year at Columbia University. In fact, his tuition fees at Columbia were paid on the grounds that he studied engineering. After a while he dropped out of the degree course but continued to write poetry. Langston Hughes’s first published poem, ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’, was in a 1921 issue of The Crisis magazine. This was to become one of his most famous poems, later appearing in Brownie’s Book and he included it in his first book of poetry, The Weary Blues in 1926.

In The Big Sea, the first volume of Hughes’s autobiography published in 1940, he describes the composition of this poem. “Now it was just sunset and we crossed the Mississippi, slowly, over a long bridge. I looked out the window of the Pullman at the great muddy river flowing down toward the heart of the South, and I began to think about what that river, the old Mississippi, had meant to Negroes in the past – how to be sold down the river was the worst fate that could overtake a slave in times of bondage . . .Then I began to think about other rivers in our past – the Congo, and the Niger, and the Nile in Africa – and the thought came to me: ‘I’ve known rivers,’ and I put it down on the back of an envelope I had in my pocket, and within the space of ten or fifteen minutes, as the train gathered speed in the dusk, I had written this poem, which I called ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers.’ ” From 1922 until 1924 he held various jobs to in order feed and clothe himself. During these years he worked as an assistant cook, in a steam laundry and as a busboy. He was also a delivery boy for a florist and worked for a time on a vegetable farm on Staten Island. He was writing all the time and Langston’s father tried to discourage him from pursuing this career in favour of something ‘more practical.’

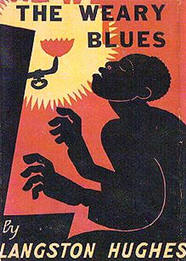

After visiting a Harlem cabaret in 1923, he wrote what is probably known as his most famous poem, ‘The Weary Blues’ and later that year he signed on as a seaman on a steamship trading up and down the west coast of Africa. He visited various ports in Senegal, the Gold Coast (later Ghana), Nigeria, the Congo, and Portuguese West Africa (later Angola). He was writing all the time and absorbing all these influences, which would emerge, sometimes years later, in his work. On a second voyage in 1924, this time to Europe, he jumped ship and settled in Paris. He worked for a few months in the kitchen of Le Grand Duc, a nightclub in Montmartre managed by an American and featuring jazz music. His poetry now starts to be influenced by jazz rhythms as well as the African music he absorbed on his visits there. In November, 1924, Langston Hughes moved to Harlem, in New York. Whether abroad on his travels, or at home in the US, Hughes loved to sit in the clubs listening to blues, jazz and writing poetry. A ‘new rhythm’ started to emerge in his writing and upon moving to Washington, D.C. in 1925, his time spent in blues and jazz clubs increased even further. “I tried to write poems like the songs they sang on Seventh Street . . . (these songs) had the pulse beat of the people who keep going.” At the same time, Hughes accepted a job with Dr Carter G. Woodson, editor of the Journal of Negro Life and History and later the founder of Black History Week in 1926. He returned to his beloved Harlem later that year, during a period that was often referred to as the ‘Harlem Renaissance.’ It was also in 1926 that his first book of poetry, The Weary Blues was published by Alfred A. Knopf.

Here we can see that Hughes is describing an evening of listening to a blues pianist and singer in Harlem. With its diction, its repetition of lines and the inclusion of blues lyrics, the poem evokes the mournful tone and tempo of blues music and gives its reader an insight into the mind of the blues musician in the poem. He employed the structures, rhythms, themes and words of the blues that he heard in the country, the city, the field, the alley and the stage. When he used the musical structures of the blues to write his poetry he most often relied on the twelve-bar blues which is the predominant structure, though there are others that predate, coexist with, or derive from it. These are often called blues in the classic form and about half of his blues poems fit this structure. From its roots in the rural South, the country blues moved to the city and took Langston Hughes with it. Rural jazz and blues musicians were travelling up the Mississippi to the cities along its banks for work and taking the music with them. He remembered hearing the blues performed for the first time when he was about six years old in Kansas City while living with his grandmother. Besides having both a love of this music and the common black folk it was created by and for, one of the reasons that Hughes began to draw on the blues tradition for writing his poetry is that he hoped to capitalize on the blues and jazz craze. Though the markets for music and poetry were quite different, he thought he could somehow merge the two. Ray Smith |

|

Return to Blues Poetry -

Introduction |