Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Background of Recorded Blues By Max Haymes

This is the sixth of a series of short surveys on the content and meaning of some early blues which takes in the social, economic and cultural strands of the life-situation for Blues singers in the first decades of the 20th century. The appreciation of some titles will also be included. The early Blues, at its highest level, is art (working-class art) every bit as much as say the works of Picasso or Beethoven. Indeed, in a hand-out on one of the courses I teach, I hailed Charlie Patton as "the Beethoven of the Blues".

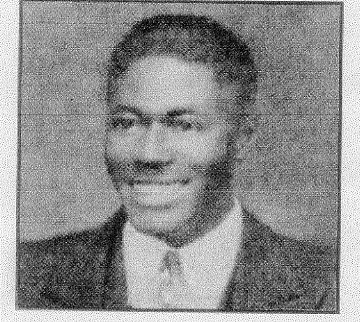

No. 6 Big Ship Blues - Kokomo Arnold. 1937.

In the early recorded Blues era (1890-1943) there are many references to working/travelling in boats on the rivers in the South - "big boat's up the river", "I went down to the landing to see if my boat was there", "the boat's in deep water on a bank of sand", depth soundings by lead callers (from whence Mark Twain derived his pen name), as well as particular steamboats such as the Jim Lee. But it seems that songs about ships are a rare species (Footnote 1). For the completely 'land-locked', a steamboat and a steamship differ insofar as "the location of where the craft was designed to operate. A ‘boat’, no matter its size, is built to run on inland waterways, while a ‘ship’ is fashioned for ocean travel". (1). There were of course the coastal steamboats that plied their trade "in generally unprotected waters" (2), i.e. at sea along the coast line. I have drawn heavily on two tomes by railroad connoisseur Richard E. Prince: "Seaboard Air Line Railway" and "Atlantic Coast Line Railroad", for which I am heavily indebted.

The Kokomo Arnold song under consideration was one of this rare species of recorded blues and surely unique in describing a sea journey which included an Atlantic storm and a bout of seasickness! Sleeve-note writer David Harrison quoted the lyrics of "Big Ship Blues" and asked (in 1968) : "Is it possible perhaps that Arnold actually experienced the journey he so evocatively describes?" and "Could he have gone on a transatlantic cargo ship trip from New York to Spain?". As an alternative he posits ". . . was his song influenced by accounts of the sinking of the Titanic by Rabbit Brown, Willie Johnson or Hi Henry Brown?" (3). This article in the "Background Of Recorded Blues" series attempts to answer these questions.

In a Decca recording studio in Chicago near the end of March, 1937, Kokomo Arnold sang:

1. "Now, this big ship

is a-rockin', an' my body's filled with aches an' pains. (x 2)

Now, if I git

'cross the Atlantic Ocean, good people, I will not live to Spain."

2. "Now, this big tide

is risin', you better lower your anchors down. (x 2)

Now, if we

don't make the circle, we never will get back to New York Town."

3. "Ah!

Why don't you people quit laughing? I feel mighty sad in my mind;

Now, why

don't you people quit laughing? I feel mighty sad in my mind.

Yes, this

big storm goin' a-risin', an' a cyclone is right behind."

4. "Now,

1 feel bad. Nobody seems to want to go my way;

Now, I feel

sad. Nobody seems to want to go my way.

Says, this

big ship gain' to leakin', right between midnight an' day."

5. "Now, I see somethin' shinin', daylight is

breakin' all around. (x 2)

Soon as we

make a few more notches, I will be right back in New York Town."

(4)

It is of course only in his opening words that Arnold conveys to the listener that he is referring to a transatlantic crossing rather than a coastal trip. But African Americans have been involved with labour on steamboats and ships since antebellum times when some freedmen would help make up a ‘chequer board crew’ (i.e. black and white).

The small percentage of ‘free’ blacks experienced only a very limited sense of liberty in their daily lives and so it was on ships. I'm sure that a report of the black section of a crew being forced to stop on board for 2 or 3 days in Mobile Bay, while their white counterparts enjoyed shore leave is not an isolated one.

Freight ships, or freighters, transported various cargoes such as pitch, tar, lumber, and coal to virtually all points of the compass; including Europe and Britain. Liverpool was an important port of call and the main reason was another commodity - cotton. This was of course to feed the great cotton mills in Manchester, Wigan, Lancaster, and many others all over the North of England. To maximize profits, in the jargon, merchants aimed to pack as much cotton onto a ship as possible (as indeed with steamboats). To achieve this end, the compress or ‘cotton press’ appeared all over the U.S. Naturally, the South had more than its fair share of these. The sole reason for the existence of the compress was "to reduce the size of cotton bales for Ocean shipment". (5).

The

railroads, as the first industry in the U.S., played an important part in this

export of cotton, and increasingly so towards the end of the 19th

century. The Seaboard Cotton Press Company had a building in Norfolk, Va. in the

late 1880s which was later acquired by the Atlantic & Danville Railway in "the

early Nineties" (6) which in turn was absorbed into the Southern Railway by the

turn of the 20th. century. It was the Southern that served Kokomo's

original home at Lovejoy, or Lovejoys Station, in Georgia. By 1900 the Seaboard

Air Line Railway (S.A.L.) was formed from a conglomerate of companies and also

had "cotton compresses at Hamlet, Raleigh, and Savannah". (7). Raleigh and

Hamlet are in North Carolina and of course Savannah is in Kokomo's home state of

Georgia. The S.A.L. main line ran from Norfolk via Portsmouth, Va. on down to

Port Tampa in Florida and beyond. Seaboard, N.C. is a small town on the line

just east of the Roanoke River. Lovejoy's Southern rail connection linked with

an important junction at Americus, Ga. with the S.A.L. The latter was a direct

route, of some 70 miles length, to Savannah. This was also Blind Willie McTell

territory and both these cities appear in blues by this titan of the 12-string

guitar. As indeed

did the Southern Railway feature in Kokomo Arnold's repertoire: "Southern

Railroad Blues” and “Lonesome Southern Blues" (both in 1935) for example.

(Footnote

2).

The

railroads, as the first industry in the U.S., played an important part in this

export of cotton, and increasingly so towards the end of the 19th

century. The Seaboard Cotton Press Company had a building in Norfolk, Va. in the

late 1880s which was later acquired by the Atlantic & Danville Railway in "the

early Nineties" (6) which in turn was absorbed into the Southern Railway by the

turn of the 20th. century. It was the Southern that served Kokomo's

original home at Lovejoy, or Lovejoys Station, in Georgia. By 1900 the Seaboard

Air Line Railway (S.A.L.) was formed from a conglomerate of companies and also

had "cotton compresses at Hamlet, Raleigh, and Savannah". (7). Raleigh and

Hamlet are in North Carolina and of course Savannah is in Kokomo's home state of

Georgia. The S.A.L. main line ran from Norfolk via Portsmouth, Va. on down to

Port Tampa in Florida and beyond. Seaboard, N.C. is a small town on the line

just east of the Roanoke River. Lovejoy's Southern rail connection linked with

an important junction at Americus, Ga. with the S.A.L. The latter was a direct

route, of some 70 miles length, to Savannah. This was also Blind Willie McTell

territory and both these cities appear in blues by this titan of the 12-string

guitar. As indeed

did the Southern Railway feature in Kokomo Arnold's repertoire: "Southern

Railroad Blues” and “Lonesome Southern Blues" (both in 1935) for example.

(Footnote

2).

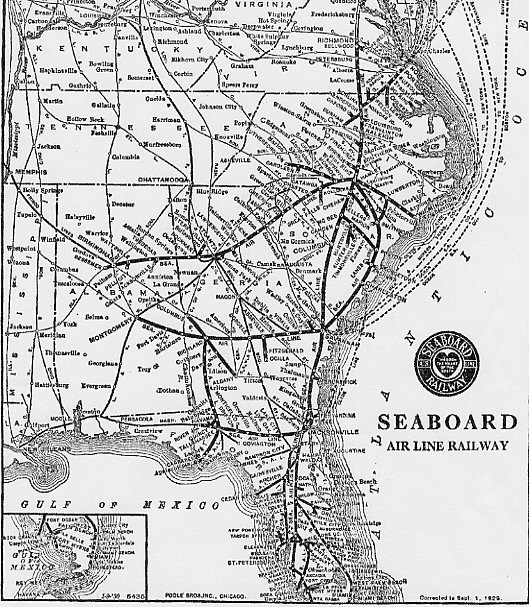

Map

of the SEABOARD AIR LINE

RAILWAY COMPANY

as of 1930.

Savannah is one of the South's oldest and most picturesque cities. It was "a principal cotton port in earlier years and also engaged in the shipment of naval stor and lumber, as well as other products of the South. A cotton compress was located on a Seaboard pier." (8). Like Norfolk, Va., Savannah was "another important seaport of the SEABOARD AIR LINE which owned vast deep sea terminals on Hutchinson Island in the Savannah River, opposite the city." (9). (Footnote 3). Ocean-going ships sailed between Savannah, New York City and Boston as well as Charleston, S.C. to Norfolk. The S.A.L. reached Atlanta, Ga. in 1892 and built a cotton compress at the afore-mentioned Hamlet in North Carolina. From there "direct rail lines carriedcompressed bales of export cotton to the Atlantic ports of Portsmouth, Wilmington Savannah, and later Charleston." (10). Prince adds: "Norfolk and Portsmouth soon became among the largest cotton ports in the world." (11), at least up to the late 1920s. Kokomo Arnold might have worked on one of these ocean-going ships and recalled his trip in "Big Ship Blues".

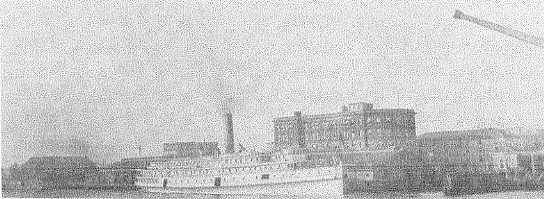

S.S. Florida moored at the S.A.L. passenger wharf

and railroad depot on the Portsmouth waterfront in 1915.

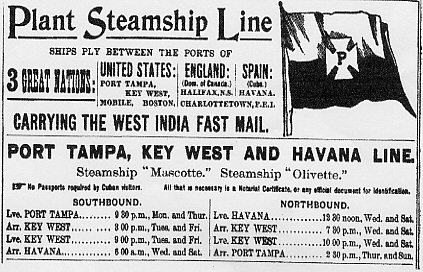

However, Arnolds reference to Spain might indicate a rather shorter, if no less unpleasant, Atlantic crossing. As well as the Southern and the S.A.L., several other of the major Southern railroads also got involved in steamship companies with an eye on the overseas trade. One of these was the group of roads known as the Plant System which served western and central Florida as well as points in Georgia, Alabama, and S. Carolina. Named for Henry B. Plant the man who almost single-handedly ran the system of 2,220 miles of track as well as several famous hotels and steamship concerns. The latter included the Plant Steamship Line commencing in 1886 "with Port Tampa as its base of operations". (12). A decade later this company advertised their schedule including the West India Fast Mail and "THROUGH PULLMAN SLEEPERS" from "New York to Port Tampa, via WEST COAST LINE". (13). The ad. points out the departure times of the "only trains connecting with ships" (14), on a route through Alabama, Florida, and Georgia. Two of these stations in the Peach Tree State being Savannah and Waycross. The latter being celebrated in "Waycross Georgia Blues" from 1928 by Barbecue Bob; it was one of the major railroad junctions in the South. It is interesting to note that included in this 1896 publicity sheet at the top of the page under "3 GREAT NATIONS", are the headings not only of the U.S.A. and England (sic) but also "SPAIN" with "Cuba" printed in brackets underneath.

Part of a schedule of the Plant Steamship Line

in 1896

This was two years prior to the Spanish-American War in 1898 and as a colonial possession, Cuba was obviously regarded by Americans as being within the Spanish border. Referring to Cuba as "Spain" before 1898 was presumably quite a common practice, for the Plant Steamship Line to use it in their advertisement. It continued to be so into the 1920s - at least on some blues recordings. In 1926 Coot Grant cut her "Stevedore Man" on the Paramount label accompanied by an excellent small jazz outfit.

"Woke up this mornin', ‘bout

half-past nine;

An’ I just could not keep from cryin’.

I was worried about that stevedore man of mine."

"Now, my man must be gone to

Spain;

Lord, I hate to call my sweet daddy's name.

Ohhh! How I miss him so."

"It's rainin' an' it's hailin'. Stormin', daddy, on the

sea;

An' that's the onliest way to keep my good daddy away from me."

(15).

Her "good daddy" was obviously not just loading/unloading ships at the dockside (the usual role of a stevedore) but was also employed as a crew-member on an oceangoing freighter. Coot Grant was to re-make this title as "Stevedore Blues" (Cameo 9240) near the end of 1928, but the lyrics were virtually the same. Also in 1928, Memphis bluesman Furry Lewis included the following lines on his "Mistreatin' Mamma" (Vi 38519).

"I got a woman in Cuba, got a woman in Spain;

Woman in Cuba, got a woman in Spain.

I got a woman in Chicago an' I'm scared to call ‘er name."

(16)

Although the way Furry pronounces it, the word comes across as "Cupid"!

II

The "circle" in Kokomo Arnold's second verse presumably refers to the harbour in New York City, while the unusual phrase in his closing lines has at least 2 alternatives. "Soon as we make a few more notches" (Harrison hears "matches") could just refer to cranking up the power of the ship's engines to get back home that much quicker. Or a more blues-related definition might derive from cant (criminal slang) as noted by Partridge. The 3rd. listing under ‘notch’ reads: "To have got a notch is to be drug-intoxicated: U.S.A. : Aug. 15, 1931, Flynn's, C.W. Willemse, extant. To be a notch higher: cf. high". (17). "Flynn's" was an American magazine started in 1924 and by 1928 became "Detective Fiction Weekly" until its final issue in 1942. (18). In a recording made some 7 months after "Ship", Arnold makes a reference (also rare in Blues) to just such a recipe to become "drug-intoxicated".

"Now, I'm gonna smoke my reefer, drink my good champagne

an' wine. (x 2)

Say, I ain't gon' let these hard-headed women make me lose my mind."

(19)

III

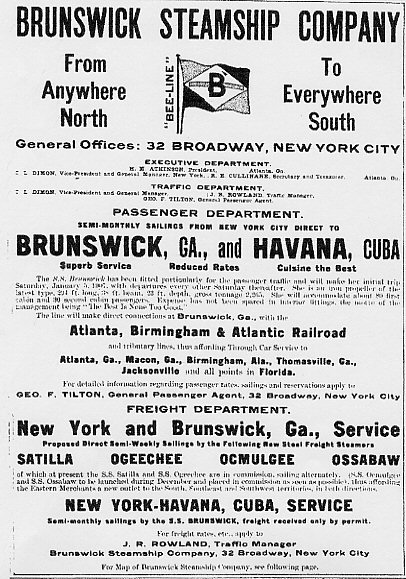

Of more relevance is the fact that Coot Grant's (aka Leola B. Wilson) husbands both came from Florida coastal cities. Isaiah Grant, whose name she kept for recording purposes, was "born in 1886 in St. Petersburg", (20) which is situated some 6 miles west of Tampa on the old Tampa Bay. While her second husband, Wesley "Kid"" Wilson, was "born in 1893" (21), as was Coot Grant, in Jacksonville over on the east coast near the Georgia state line. Certainly, in the case of husband No. l, he probably worked on the P. & O. Line out of Port Tampa in the early 1900s. Not to be confused with the world-famous Cunard line of the same initials, this was the Peninsula & Occidental Steamship Company formed in 1900 when the Florida East Coast Steamship Co. "combined assets with the Plant Steamship Company" (22). Or Isaiah Grant would have found gainful employment at his home base as another major railroad, the Atlantic Coast Line, "took over ... the SANFORD & ST. PETERSBURG RY. in 1902 along with other lines of the PLANT SYSTEM" (23). The A.C.L. ran up through central and eastern Florida en route to Washington D.C. On the way it served the ports of Jacksonville, Fla. as well as Savannah and Brunswick in Georgia. The latter was also served by the Brunswick Steamship Company from 1906 until it sold its "five freighters in 1911 to the Atlantic, Gulf and West Indies Steamship Company (AGWI Lines)" (24). Brunswick was some 200 miles south-east of Lovejoys Station and a connection from Atlanta to Brunswick was easily accessible to Kokomo Arnold.

Freighters like SS Onsalow

and SS Altamaha

plied a regular trade between New York and Brunswick, Ga. As early as 1881 the

228-ton side-wheeler

H.B. Plant

was "operated in daily

service between

Ferandina, Fla. and

Brunswick, Ga., making connections with trains at both ports." (25). This would

include trains from Waycross, Ga.

Brunswick Steamship ad. December 1906

Conclusion

Some of the occasions I've come across the ship, as opposed to ‘boat’, in the early blues are noted here. Recorded prior to the Coot Grant title, are blues by the famous ‘Smith girls’ - Bessie and Clara. The very first one seems to be "Deep Blue Sea Blues" by Clara Smith, recorded in 1924 for Columbia. (Footnote 4).

1. "My man's on the

ocean, bobbin' up an' down;

He belongs to

other vamps but 'e's always on my mind.

Girls, take a

tip from me;

You know how

I feel when my man at sea."

2. "I

get the blues for the deep blue sea;

Nothing but a

ship can satisfy me.

New York to Mobile can change my mind;

I feel like

getting' in a aeroplane an' flyin'."

3. "When I hear that

whistle blow;

I know the

ship is made the shore.

Ain't but one

man an' this is one that can satisfy me;

That's the

man that reels an' rockin' on the deep blue sea.

I mean, the

deep blue sea."

(26)

There is more than a hint at a possibility of seasickness in the second verse while she is sailing from New York City down to Mobile Bay. Clara followed up the ‘ship theme’ in 1925 with "Shipwrecked Blues" on 17th. January which remains un-issued. However, Columbia did issue her next version some 3 months later. A superb side, with Louis Armstrong on cornet, this is as unique as Kokomo Arnold's "Big Ship Blues". Clara Smith takes on the persona of a ship's captain abandoned by her crew and about to sink beneath the waves; "singin' the `Shipwrecked Blues"' (27). One of her contemporaries, Sara Martin, was to do a version in 1926 on Okeh. Bessie Smith's "Shipwreck Blues" was a different song. The title is used in symbolic fashion to illustrate a state of mind. (Footnote 5). Otherwise there are no marine references in her blues. The same could be said for "Ocean Blues" by Teddy Moss in 1929, as well as "Ocean Wide Blues" and "Ocean Wide" by Georgia Slim and ‘The Za Zu Girl’; both in 1937. The latter singer was Victoria Spivey's elder sister, Elton Spivey. Two other recordings of "Ocean Blues" (which might be 2 versions of one song) remain elusive to the Blues world at large. The earliest in 1928 is by Octavia Dick which remains a Vocalion un-issued side. While the Washboard Sam title, and his first recording, from 1935 on Bluebird (BB B5983) has yet to be discovered.

However, one superb blues by Lonnie Johnson, from 1927, has come down to us. This includes lines such as being "miles an' miles from shore" and seeing the U.S. coast guard coming to rescue the passengers from the drifting life boat (wearing their 'life-savers', or life belts). While Johnson declares their American nationality and patriotism:

"Uncle

Sam's ship was comin', painted in red, white an' blue. (x 2)

We say we live in New York City, red an' white, blue, brothers, all the way

through."

(28)

Clara Smith's recordings possibly inspired Coot Grant, Lonnie Johnson (a great admirer of Clara), and later Bessie Smith, to commit their songs to disc. Johnson's is only one of 4 titles cut in the 1920s that deals with ships and the sea as the main/only theme. These being: "Deep Blue Sea Blues" and "Shipwrecked Blues" by Clara Smith and "Stevedore Man"/Blues" by Coot Grant. The fifth had to wait until the late 1930s, "Big Ship Blues" by Kokomo Arnold. This should hopefully answer the questions asked by David Harrison in 1968 - which inspired this article.

Footnote 1: I am excluding the group of songs about the Titanic

and the two titles "West Indies Blues" and "Black Star Line. Both of these refer

to one-off historical events well-known to the U.S. black communities at the

time. The latter two songs were in support of black leader Marcus Garvey and his

short-lived 'back to Africa' movement in the early 1920s.

Back

Footnote 2: See "Railroadin' Some" (railroads in the early

blues). Max Haymes. 2005. Publication pending. For more detail on Kokomo Arnold,

Lovejoys Station and circuses -Ch. 8 "Carried Water For The Elephant".

Back

Footnote 3: In the latter part of the 19". c. several railroads

referred to the most direct or 'straight' route as an 'air line'.

Back

Footnote 4:The same title by Tonuny McClerman (aversion of "Catfish") and Texas

Alexander are unrelated to Clara's song. As is "Deep Blue Ocean Blues" by Harry

Chatmon (a version of "'I"Ain't Nobody's Business If 1 Do"). These sides use the

sea in the same way as Bessie Smith does on her "Shipwreck Blues" - that is, as

symbolism. "Deep Sea Blues" by Q. Roscoe Snowden is a piano solo. While this

title also by Lonnie Johnson and Ida Cox (1930 and 1939 respectively) remain

unheard by me. But see main text and Johnson's earlier "Life Saver Blues" in

1927.

Back

Footnote 5:

Most famously done in post-war years by Charles Brown on his "Driffin' Blues"

and covered by diverse artists such as Ray Charles and Chuck Berry.

Back

Notes

| 1. | Huddleton D., S. C. Rose,& Pat T. Wood. | p.17. |

| 2. | Ibid. | |

| 3. | Harrison D. | Notes to Matchbox L.P. |

| 4. | "Big Ship Blues" | Kokomo Arnold vo.gtr. 30/3/37. Chicago, Ill. |

| 5. | Prince R.E. | p.55. ("Air Line") |

| 6. | Ibid. | |

| 7. | Ibid. | |

| 8. | Ibid. | |

| 9. | Ibid. | |

| 10. | Ibid. | |

| 11. | Ibid. | p.229. |

| 12. | Prince R.E. | p.44. ("A.C.L.") |

| 13. | Ibid. | pA9. |

| 14. | Ibid. | |

| 15. | "Stevedore Man" | Coot Grant vo.; unk. cor.; unk. tbn.; unk. cit.; unk. pno. c. May-June, 1926. Chicago, Ill. |

| 16. | "Mistreatin' Mamma" | Furry Lewis vo.gtr.28/8/28. Memphis, Tenn. |

| 17. | Partridge E. | p.475. |

| 18. | Ibid. | See un-numbered page under "Abbreviations And Principal Short References". |

| 19. | "Rocky Road Blues" | Kokomo Arnold vo.gtr.23/10/37. Chicago, Ill. |

| 20. | Vanco J.H. | Notes to Document CD. |

| 21. | Ibid. | |

| 22. | Bramson S.H. | p.53. |

| 23. | Prince. | Ibid. p.30. ("A.C.L.") |

| 24. | Ibid. | p.67. |

| 25. | Ibid. | p.44. |

| 26. | "Deep Blue Sea Blues" | Clara Smith vo.; Coleman Hawkins ten. sax.; Fletcher Henderson pno.19/8/24. New York City. |

| 27. | "Shipwrecked Blues" | Clara Smith vo.; Louis Armstrong cor.; Fletcher Henderson pno. |

| 28. | "Life Saver Blues" | 2/4/25. New York City. Lonnie Johnson vo.gtr.9/11/27. New York City. |

References

| 1. |

Huddleston Duane, Sammie Cantrell Rose & Pat Taylor Wood. |

"Steamboats And Ferries On The White River". New ed.University of Arkansas Press.Fayetteville. 1998. 1st.pub.1995. |

| 2. |

Harrison David. |

Notes to "Kokomo Arnold" L.P .Matchbox. SDR 163. 1969. |

| 3. |

Prince Richard E. |

"Seaboard Air Line Railway".Indiana University Press.Bloomington, Indianapolis.2000. (Rep.). 1". pub. 1966. |

| 4. |

Prince Richard E. |

"Atlantic Coast Line Railroad'".Indiana University Press. 2000.(Rep.). 1". pub. 1966. |

| 5. |

Partridge Eric. |

"A Dictionary Of The Underworld". Wordsworth Edition Ltd. 1989. (Rep.). 1st. pub. 1950. |

| 6. |

Vanco John Henry. |

Notes to "Coot Grant And Kid Wilson Vol. 1 1925-1928". Document DOCD-5563. 1997. |

| 7. |

Bramson Seth H. |

"Speedway To Sunshine" (The Story Of The Florida East CoastRailway). Rev. ed. The Boston Mills Press. 2003. (Rep 1st.pub. 1984. |

| 8. |

Transcriptions by Max Haymes. |

|

| 9. | Discographical details from "Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943". 4th. ed. (Rev.). Robert M.W. Dixon. John Godrich & Howard W.Rye. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1997. | |

| 10. | Corrections and additions by Max Haymes. |

Illustrations

|

l. |

Prince. |

Ibid. p.55. ("S.A.L.") |

|

2. |

Ibid. |

p.4. |

|

3. |

Ibid. |

p.60. |

|

4. |

Prince. |

p.49. ("A.C.L.") |

|

5. |

Ibid. |

p.69, |

|

6. |

Yazoo 2068. |

Notes to C.D. "Times Ain't Like They Used To Be". Vol. 8. 2003. |

Max Haymes

Essay © Copyright 2005 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Website © Copyright 2000-2006 Alan

White. All Rights Reserved.

Check out the other essays in the "Background of Recorded Blues" series:

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 1 - Pea Vine Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 2 - Mobile and Western Line

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 3 - Beaver Slide Rag

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 4 - P.C. Railroad Blues

Background

of Recorded Blues: No. 5 - Nut Factory Blues