|

Chapter I

In the history of recorded blues, it was generally

the more urban singers who were first immortalized on wax running at 78

revolutions per minute. After the historic break-through of Mamie Smith

(the first black blues singer on record) with Crazy Blues in

1920, this opened the floodgates, because of the unexpected and

staggering response from the black working-class population; for many

more female artistes whose singing styles covered the whole range of

what was to become known as vaudeville-blues (nee ‘classic blues’).

Singers such as Edith Wilson, Rosa Henderson, Edmonia Henderson, Bessie

Smith. Clara Smith (not related), Ma Rainey and Bertha ‘Chippie’ Hill,

all contributed to the blues scene in the early 1920s. Ranging from the

lighter more vaudeville blues of Edmonia Henderson and Edith Wilson,

through the more bluesy Rosa Henderson (both Hendersons also not

related), to the ‘heavy’ blues of Rainey, both the Smiths and Chippie

Hill. Of course some of these singers, like Ma Rainey continued to

record until the end of the decade, with Bessie and Clara Smith going on

into the early 1930s.

In the ensuing dash to maintain the momentum of this

new source of income, the record companies scoured the big cities for

more talent. The reason for this was that the vaudeville blues singers

worked the theatre/cabaret circuit accompanied by various jazz groups

and bands who in themselves contained some illustrious names, King

Oliver and Louis Armstrong among them. As the fountain began to run

dry, the record companies began to search further afield, literally, as

they went ‘into’ the countryside, and between 1924 and 1926 with

recording debuts by Papa Charlie Jackson, Blind Blake, Bo Weavil

Jackson, Peg Leg Howell, and Blind Lemon Jefferson, the rural or country

blues had “arrived”. Of course in the evolution of the blues, some

thirty years old by 1920, the complete opposite was the case. In any

event, this paved the way for a whole host of country blues singers and

musicians such as the immortal Charlie Patton, Barbecue Bob, Texas

Alexander, Bukka White, Memphis Minnie, Bessie Tucker, Son House, Robert

Johnson, Memphis Jug Band, et al.

Unlike the earlier vaudeville blues singers who,

generally speaking did not play an instrument on their recordings, the

rural artists, in the main, used their own accompaniment. This usually

featured just a guitar or piano, and sometimes a harmonica, a fiddle, or

a second guitar were added. Also incorporated were rough unorthodox

instruments like a kazoo, jug, an imitation bass, washboard, and so on.

Many of these singers were decidedly not ‘sophisticated’. They

sang blues of 12-bars, 16-bars, 13½-bars, or no bars at all! Their

voices were sometimes rough, archaic-sounding and barely comprehensible,

and again sometimes clear and nearer white. Between these two extremes

were an endless variety of vocal styles including falsetto, moaned

choruses and antiphonal ‘call and response’ where the guitar becomes a

second voice which completes the half-sung line. Many of these blues

singers were itinerant beggars and ramblers, never staying in one place

very long before ‘hopping a freight’ and letting a train take them to

pastures a-new or walking ‘on down that old lonesome road’, often having

to live by their wits through lack of employment and the oppression of

the insidious Jim Crow segregation laws; it was especially tough for the

blind singers.

It was one of the latter and one of the greatest

blues men, Blind Willie McTell, who on a wintry day in November, 1940,

cut the first known recording of Crapshooter in the style of the

rural blues, in Atlanta, Georgia (McTell’s home state) for the Library

of Congress based in Washington D.C. It was a song he was to re-record

on two more occasions in the post-war period.

Table

A

|

Title |

Date/location |

Recording

Co. |

|

1. |

Dying Crapshooter’s Blues |

5/11/40. Atlanta, Georgia. |

L. of C. |

|

2.

|

Dying Crapshooter’s Blues |

-/-/49. Atlanta, Georgia. |

Atlantic |

|

3.

|

Dying Crapshooter’s Blues |

-/-/56. Atlanta, Georgia. |

Bluesville |

Although McTell had started his recording career as

early as October, 1927, for Victor Records, a commercial company, he did

not include Crapshooter in his repertoire; and like the potted

history of blues above, it was first recorded under the broad umbrella

of the vaudeville-blues with a small jazz group accompaniment, by Martha

Copeland in the same year. In the following month of June, Mamie

McKinney cut her version with Porter Grainger on piano but it remains

unissued. Viola McCoy recorded Crapshooter in late August with

a similar line-up to Martha Copeland. The following month Rosa

Henderson put out her version accompanied by Cliff Jackson on piano; and

remained the last recording of this particular blues until November 1940

in Atlanta. These four performances of Dying Crapshooter’s Blues,

as far as we know, are the sum total committed to wax (excluding

McTell’s version) in the pre-war blues era of 1890-1943. All four

female singers were vaudeville blues artists more at home in a jazz

setting. The recordings were all made within five months of each other

and they were all made in New York City.

Table

B

|

Title |

Artist |

Date/location |

|

1. |

Dyin' Crap-shooter’s Blues |

Martha Copeland |

5/5/27. New York City. |

|

2.

|

Dyin' Crapshooter’s Blues |

Mamie McKinney |

24/6/27. New York City |

|

3.

|

Dyin' Crapshooter’s Blues |

Viola McCoy |

c. late August 1927. New York City. |

|

4. |

Dyin' Crap-shooter’s Blues |

Rosa Henderson |

c. late September 1927. New York City. |

Blind Willie McTell’s first known recording of

Crapshooter as has already been stated was in November, 1940,

and as part of his introduction to this version he states “I am

gonna play this song that I made myself, originally this is from

Atlanta” (see

Appendix.I). This statement also has

strong significance when tracing the path of Crapshooter’s

origins which we will return to later. McTell’s third and final

version has a lengthy spoken introduction including the claim “I

started writin’ a song in ’29, though I didn’t finish it, I didn’t

finish it til 1932.” (see

Appendix II) But despite

this statement, I believe that 1927 was the year that McTell wrote

Dying Crapshooter’s Blues, or at least the best part of it.

I would now like to indulge in a little linguistic detective work!

By the time of his last session (1956) his memory

was not so quick (the effect of prolonged hard drinking?) as at the

time of his interview with Alan Lomax, the famous American

folklorist, in 1940. Besides the repeated words in the last quote

by McTell, this phenomenon occurred on three other occasions during

his introduction, plus one re-utterance three times! Plus two other

mistakes where he corrected himself (see

Appendix II).

Off-hand I can only recall one spoken mistake in the entire

interview conducted by Lomax some sixteen years earlier. So I am

saying he was mistaken in his remembrance of the year of

Crapshooter’s authorship, and did not correct himself on this

occasion. This would seem to indicate another downward spiral in the

condition Willie McTell’s memory, which would have been more

obviously apparent if another hypothetical ‘last session’ could

have been held some sixteen years further on, in 1972. (He died in

1959).

Eminent American blues authority, Sam Charters,

says of the 1940 version of Crapshooter’s: “This personal

reworking of the old ‘Streets of Laredo’ theme is one of

McTell’s masterpieces, and this version, which seems to have been

recorded not long after he wrote it , since he didn’t do it on

earlier sessions, has a clarity of musical detail that the two later

versions lack,” (1)

[Footnote 1: I find it intriguing to note that, apart

from Charters and myself, there is only one other blues writer who

makes any connection between this song and Crapshooter.

Richard Spottswood says of the McTell composition, that it “is

another version of the old bawdy funeral chant best known to most as

the expurgated ‘Streets of Laredo’.” (2) ] Thus

Charters would appear to put the date of authorship of

Crapshooter somewhere between 1935 and 1940, when a quick glance

at Table B would put it at least eight years earlier. Just because

Willie McTell didn’t record it then, could be down to a number of

reasons. Self-censorship if he thought the song too blasphemous or

‘over the top’. Or Victor Records might have heard it and censored

it for the same reason, or maybe because of the sudden ‘rush’ of

cover versions (see Table B) before his own initial recording

session; perhaps neither he or Victor thought there would be any

mileage in adding another version (albeit the original!) to the

list, in October, 1927. In any event, McTell could have seen it fit

to shelve the song until his recording sessions for Decca in 1935,

if one title Dying Doubter Blues is possibly his true first

recorded version of Crapshooter. We may never know as this

remains an unissued item. If it was the case, then it might seem a

natural selection for McTell in November, 1940, when Lomax gave him

virtually an ‘open cheque book’ as far as material was concerned,

for the Library of Congress.

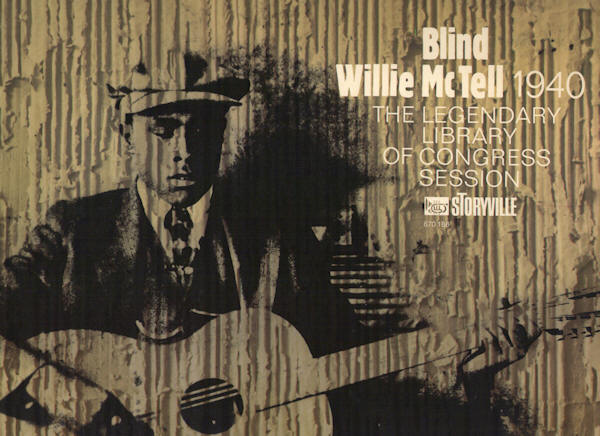

Label shot from

Max Haymes' collection - used with permission

As this singer had been musically active for

several years before his recording debut in 1927, it would be fairly

safe to assume that he wrote Crapshooter sometime in the

first four months of that same year, but did not record it until

1940. This would at least explain the small ‘glut’ of cover

versions just discussed, if not the total absence of rural

recordings of the song at the time. Perhaps it would be more

accurate to say that McTell completed Crapshooter in

1927 although starting it a couple of years earlier.

Quoting a song called Rollin’ Mill, Odum

and Johnson reveal the third verse as follows:

| |

Carried him off in hoo-doo wagon, |

| |

Brought him back wid his feet a-draggin’, |

| |

O babe, O babe! (3) |

It is possible that the above was collected from

an unknown singer, in 1925, whom McTell heard in person and got his

phrase ‘hoo-doo wagon’ from them. I believe that it was McTell, in

any event, that first popularized or even thought of, the

replacement phrase ‘one foot up, a toenail dragging’. Another source

of inspiration could have come from a ballad called Dis Mornin’,

Dis Evenin’, So Soon. This describes how a man leaves his wife

in the morning to go downtown ignoring her warning of possible

danger to himself as a coloured man; and his wife has her worst

fears realized “ ‘when she got word dat Bill was dead’. The final

verse is a scenario for a pantomime”. (4)

In view of the subject matter, either Sandburg knew little of

working class black culture or he had a grim sense of humour! The

last verse runs:

| |

Dey brought Bill

home in a hurry-up wagon dis mornin’, |

| |

Dey brought Bill

home in a hurry-up wagon dis evenin’, |

| |

Dey brought Bill

home in a hurry-up wagon, |

| |

Dey brought Bill

home wid his toes a-draggin’, |

| |

Dis mornin’, dis

evenin’, so soon. (5) |

The

‘hurry-up wagon’ has a parallel in McTell’s ‘hoo-doo wagon’, and of

course the phrase ‘toes a-draggin’’ is very similar to his ‘a toenail

dragging’. Some thirty odd years later, McTell’s phrase crops up in a

blues by another Georgia singer/guitarist, William Robertson (aka Cecil

Barfield) who included it in the following verse of a totally unrelated

song:

| |

You go into town

in the hoochie coochie wagon, |

| |

With my heels

turned up an’ my toenails draggin’. (6) |

This would

seem more than coincidental with McTell’s lyrics and would point to the

latter having probably created this verse. In passing, while it is not

clear when the Sandburg verse was collected, the ‘plantation’

phraseology of ‘dis, ‘dat’, and ‘de’ puts it in the nineteenth century,

probably in the latter half. Carl Sandburg’s source for this song is

“Nancy Barnhart, painter and etcher, of St. Louis.” (7)

In all three songs quoted, by the use of the slang term for a hearse,

‘hoodoo wagon’, etc., would seem to indicate a superstitious attitude of

fear to death, as seen from a purely secular point of view. Although

McTell recorded such philosophically religious sides as We‘ve Got To

Meet Death Some Day in the 1930s and ‘40s, it was apparently not

from any inner conviction at the time. He did not ‘get religion’ until

much later, not surprisingly, just prior to his death in 1959. (8)

Perhaps as this superstition was so strong in working class blacks at

the time, it was a main factor of so little coverage of Dying

Crapshooter’s Blues by recorded rural blues singers. This might

explain why McTell’s Dying Doubter Blues of 1935 remains

unissued. It is interesting, or coincidental (?) to note that

Sandburg’s book was published in 1927, the year of the four female cover

versions of Crapshooter, and also the year I believe Blind Willie

McTell wrote it.

We now turn to McTell’s composition and influences on

it. While via his recorded output (1927-1956), his songwriting

reputation is assured, there is generally some outside influence which

helps to generate the inspiration and this in turn moulds the

influential parts into his own personal and very often very original

vocal and musical statements. While discussing some of his songs,

during the introduction to another 1956 recording called A Married

Man’s A Fool, (itself drawn from an earlier title by vaudeville duo

Butterbeans and Susie from 1924) McTell says with disarming

honesty “... I’d jump ‘em from other writers, but I’d arrange ‘em my

way…”. So Blind Willie McTell, in 1940, introduced and sang his own

Dying Crapshooter’s Blues to the accompaniment of his fine

twelve-string guitar. (see

Appendix I).

What stands out more than anything else in this blues

is the completely unholy content and atmosphere which is the central

theme; religious followers would deem these factors as blasphemous.

This blues typifies the picture that church-going blacks had of the

blues singers and the blues in general. It was ‘devil’s music’, evil,

encouraged promiscuity and drunkenness, etc. The main constituent of

this unholy atmosphere is what I will call the ‘numbers request’ motif;

‘sixteen real good crapshooters’, ‘twenty-two women out of the Hamilton

Hotel’, etc. This motif, in varying degrees, is to be found running

through the majority of songs which have links with Crapshooter

going back into the eighteenth century.

The song also has an air of secular

anti-establishment present, especially regarding the ‘high sheriff’, the

solicitor ‘who jailed me fourteen times’ and the judge. But over-riding

this is the complete disregard for death itself. The thumb-nose and

devil-may-care attitudes are all-pervading in this song. Also note the

veiled reference to advanced stages of venereal disease in his friend

Jessie in verse six, via the latter’s familiarity with the ‘hotels’

referred to. Venereal disease as the cause of death, although only

implied in Crapshooter, if Jessie hadn’t been shot, he’d have

died anyway because of his dissolute habits; has a strong connection

with the songs in Group Three: namely Young Sailor/Girl Cut Down In

His/Her Prime, and some versions of St. James Hospital. And

also some of the songs in Group One: The Unfortunate Lad/Lass and

Streets Of Port Arthur. Another aspect of Crapshooter is

Jessie’s illegal action when ‘he used crooked cards and dice’. This

links with songs in Group Two (see Ch. III for details of these Groups)

such as Flash Lad, Wild And Wicked Youth, and Rake And

Rambling Boy. The theme in these songs is that the reason for

‘a-robbing on the king’s highway’ was to keep the robber’s

wife/girlfriend in fine clothes and jewelry. Although not mentioned in

the 1940 version of McTell’s song, his friend Jessie had acquired a

female partner in the 1949 and 1956 recordings. Lorraine, pronounced

‘Loreen’, obviously applied the same financial pressures for material

comfort on Jessie. As soon as his ‘luck’ changed and he was penniless

‘Sweet Loreen had packed up an’ gone’ (1956). Lyrically there is little

difference between this and the Library of Congress version, apart from

the entrance of Lorraine, or rather her exit! What is different is

McTell’s approach. The contrast is marked between performing for a

white man (Alan Lomax) and potentially for his fellow black citizens

(the blues-buying public). The 1956 version comes across as more ‘jivey’,

less somber and even more disrespectful to the subject of death. (see

Appendix II)

The group of songs that Crapshooter itself

resides in, Group Five, includes a direct link via the American song

Those Gambler’s Blues (see

Appendix III and

Appendix IV)

which possibly evolved around the turn of the 20th. Century (c. 1899).

It was around this era that the word ‘jass’ became modified to the

familiar ‘jazz’, which lends support to my theory of the approximate

dating of this song.

But before we go diving back into the past, I would

like to mention some of Crapshooter’s song contemporaries which

seem to fall into two categories. First of all there is the group of

songs which come under the various headings of St. James/Joe’s

Infirmary/Hospital which was to become a jazz standard in the late

1920s. Interestingly, the best known title St. James Infirmary

seems to have evolved out of Those Gambler’s Blues just

mentioned. Indeed, some of the songs in this group are labelled

Gamblers Blues.

Table C

|

Title |

Artist |

Date/location |

|

1. |

Gamblers Blues

(St. James Infirmary

Blues) |

Hokum Boys |

c.-/10/29. Chicago |

|

2.

|

Gamblers Blues No.2 |

Hokum Boys |

c.-/10/29. Grafton, Wisconsin |

|

3.

|

St. Joe’s Infirmary

(Those Gambler’s Blues) |

Mattie Hite |

27/1/30. New York City. |

|

4. |

St. James Infirmary |

Walter Taylor |

15/2//30.

Richmond, Indiana |

|

5. |

St. James Infirmary |

Emmet Mathews |

c.-/5/31. Grafton, Wisconsin. |

|

6. |

St. James Hospital |

Mose (Clear Rock) Platt |

-/12/33. Sugar Land, Texas. |

|

7. |

St. James Hospital |

James (Iron Head) Baker |

-/534. Sugar Land, Texas. |

|

8. |

St. James Hospital |

James (Iron Head) Baker |

-/10/34. Sugar Land, Texas. |

|

9. |

St. James Infirmary |

James Wadley |

11/12/34. Atlanta, Georgia. |

|

10. |

St. James Hospital |

James (Iron Head) Baker |

29/5/36. Washington D.C. |

Added to these pre-war recordings is an unissued

St. James Infirmary by McTell himself in 1956, down in Atlanta,

Georgia, as yet unheard by me. Of course all the foregoing are secular

by nature and the other category or songs contain all sacred items; or

to be more accurate variations of one religious theme, i.e. ‘if you stay

a sinner all your life, you will go to hell’. Virtually all the titles

allude to the gambler about to die.

Table D

|

Title |

Artist |

Date/location |

|

1. |

Dying Gambler |

Rev. J.M. Gates |

early Aug. 1926. New York City |

|

2.

|

Tell Me Where Is The Gambler |

Rev. H.R. Tomlin |

19/8/26. New York City. |

|

3.

|

Dying Gambler |

Rev. J.M. Gates |

9 or 19/9/26. New York City. |

|

4. |

Dying Gambler |

Rev. J.M. Gates |

11/9/26. Camden, New Jersey. |

|

5. |

Dying Gambler |

Rev. J.M. Gates |

c.15/9/26. New York City |

|

6. |

Wonder Where is The Gamblin’ Man |

Norfolk Jubilee Quartet |

C.-/10/27. New York City. |

|

7. |

Where Is The Gamblin’ Man |

Unk. convict group |

19/12/34. S. Carolina. |

|

8. |

Dying Gambler |

Blind Willie McTell |

23/4/35. Chicago. |

|

9. |

Dying Doubter Blues |

Blind Willie McTell |

25/4/35. Chicago. |

|

10. |

Dying Gambler

(O Save Me lord) |

Bright Moon Quartet |

21/6/35. Charlotte. N. Carolina. |

|

11. |

Death Of The Gambler |

John D.Twitty |

4/5/37. Aurora, Ill. |

|

12. |

Where’s That Gamblin’ Man Gone? |

Norfolk Jubilee Quartet |

15/7/37. New York City. |

Once more, Willie McTell himself recorded a Dying

Gambler and on this occasion it is available to us. The

much-travelled singer was far from his Georgia homeland when he recorded

a session for another commercial company, Decca this time, in Chicago on

23rd. April, 1935; which included this version of Gambler

(see

Appendix V). This originates from the Rev.

J.M. Gates’ recording of the same title in 1926, and obviously reflects

the situation with a religious bias; and it is significant that the lead

vocal is taken by McTell’s wife, Kate, who was a devout believer and

would not record blues. Certain similarities can be seen between

Dying Gambler and the sacrilegious Crapshooter. Starting

with the obvious one included in both titles, we can also see a parallel

of sorts in the unstated cause of death. Although less implied in the

religious song than in Crapshooter, one could draw conclusions

from the line ‘His body began to grow so weak, an’ things began to

shake’. The ‘numbers-request’ motif is not present, but requests there

are, nevertheless, in the final verse; and a direct connection with

Crapshooter can be made via the statement ‘My dice an’ cards will be

by my head’.

Finally, although to recall all the songs which might have a vague and

tenuous link with McTell’s blues would be an almost infinite exercise, I

feel it necessary to include a list of obvious possibilities which could

claim some connection, however nebulous, with Crapshooter in the

world of the Blues in the pre-war era.

Table

E

|

Title |

Artist |

Date/location |

|

1. |

Dying Pickpocket Blues |

Barrelhouse Welch |

c.-/1/29,. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

2.

|

Lay Some Flowere On My Grave |

Blind Willie McTell (unissued) |

14/9/33. New York City. |

|

3.

|

Lay Some Flowers On My Grave |

Joshua White |

13/11/33. New York City. |

|

4. |

Lay Some Flowers On My Grave |

Blind Willie McTell |

26/4/35. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

5. |

Let Her Go God Bless Her |

Richard & Welly [sic] Trice |

13/737. New York City. |

|

6. |

Let Him Go, Girls, God Bless Him |

Aunt Molly McDonald |

30/10/40. Livingstone, Alabama. |

It should be stressed here that similar looking

titles in print can be misleading and in fact have no bearing on the

subject whatsoever. For instance Dying Gambler’s Blues by Bessie

Smith, which she recorded three times in 1924; Gambler’s Blues by

Charlie ‘Specks’ McFadden in 1929; Gamblin’ Man’s Prayer by

Piano Kid Edwards in 1930; and the 2-part Dying Sinner’s Blues by

Tommy Griffin in 1936. Conversely, some titles can seem a little

obscure. The Trice brothers’ 1937 rendition (Table

E) gets its title from a line borrowed from

St. James Infirmary (Table C).

Some thirty-odd years later (1969-1971) the same line crops up in Bud

White’s 16 Snow White Horses.

(Footnote

2: See Rounder LP Georgia Blues [Rounder 2008. Somerville,

Massachusetts] 1970.) White

was a singer-guitarist from Richland in Georgia, also of course Blind

Willie McTell’s home state. However, the rest of the 45-year old Bud

White’s song does not appear to have any connection with McTell’s

Crapshooter. Interestingly, the only female title from the US in the

story of this song, sung by ‘Aunt’ Molly McDonald (Table

E), was a variation of this same line and

was recorded only about a week prior to McTell’s version in 1940, also

by the Library of Congress; in Livingstone, Alabama, this time. McTell

himself was responsible for another less-than-obvious title Lay Some

Flowers On My Grave (Table E)

which he first recorded for Vocalion Records in September, 1933.

However, this side was unissued and Joshua White’s ‘cover’ came out a

couple of months later for the rival ARC organization. Eventually

though McTell re-recorded it for Decca two days after his Dying

Gambler (Table D)

in 1935. (see

Appendix VI). Although the first

three verses contain the secular but respectful strand of death, by

verse four the unholy strand, by implication has taken over. With

repeated references to his ‘hot mama’; and extending his harem with

lines like ‘I left a-many gal’s heart in pain’ and ‘When I’ve bidded

this life goodbye, don’t none of you womens cry’. These lines and

the first half of verse two all share the same ‘unholy’ atmosphere of

Crapshooter.

The first title in

Table E,

Dying Pickpocket Blues was recorded with piano accompaniment some

eighteen months after the four female versions of Crapshooter and

could do with a little scrutiny. (see

Appendix VII).

‘Barrelhouse’ Welch the singer –pianist on this blues, recorded it in

January, 1929, in Chicago and seems to have adopted the secular but

respectful strand to death. The first two verses incorporate a similar

theme to be found in not only Crapshooter but some of the earlier

variants as well; such as Tarpaulin Jacket (see

Appendix XII)

and The Dying Cowboy (see

Appendix XIII). That is that

the dying man’s friends are gathered round his death-bed (although only

implied in Cowboy) so that they may hear his last words

and requests. This is only a short step to the ‘numbers-request’ motif

so prevalent in Crapshooter. As Welch, or Welsh, recorded his

blues at the beginning of 1929, obviously any inspiration he got for

writing Pickpocket must have come from a year or two earlier,

possibly from McTell’s composition in 1927. Although recorded in

Chicago, it could be significant that Dying Pickpocket Blues with

its ballad-like theme set in the New York City workhouse

(Footnote

3: See Riverside LP. Piano Blues 1927-1933 [Riverside 8809. New

York City] c. 1965.)

was set in the same city in which the four cover versions of Crapshooter

were recorded.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Essay (this

page) © Copyright 2012 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

| |

|

Introduction

|

|

Chapter I

|

|

Chapter II

|

|

Chapter III

|

|

Appendix I

|

"Dying

Crapshooter's Blues" by Blind Willie McTell, 5/11/40, Atlanta, Ga. (L.

of C.) |

Appendix II

|

"Dying

Crapshooter's Blues" by Blind Willie McTell, 1956, Atlanta, Ga. (Bluesville) |

Appendix III

|

"Those

Gambler's Blues" ("The American Songbag", Carl Sandburg) |

Appendix IV

|

"Those

Gambler's Blues" ("The American Songbag". ibid.) |

Appendix V

|

"Dying

Gambler" by Blind Willie & Kate McTell, 23/4/35. Chicago, Ill. |

Appendix VI

|

"Lay Some

Flowers On My Grave" by Blind Willie McTell, 25/4/35, Chicago, Ill. |

Appendix VII

|

"Dying

Pickpocket Blues" by Barrel House Welch, -/1/29. Chicago, Ill. |

Appendix VIII

|

"The Flash

Lad" |

Appendix IX

|

"In Newry

Town" ("Folk-Song Society Vol. 1." Ed. A. Kalisch. c. 1905.) |

Appendix X

|

"The Wild

And Wicked Youth" Vsn 2 ("The Constant Lovers" Ed. Frank Purslow. 1972.) |

Appendix XI

|

(Unused) |

Appendix XII

|

"The

Tarpaulin Jacket" written by George Whyte-Melville. c. 1855. |

Appendix XIII

|

"The Dying

Cowboy" ("The Penguin Book of American Folk Songs" Alan Lomax. 1964.) |

Appendix XIV

|

"The Young

Sailor Cut Down In His Prime" ("The Everlasting Circle" J. Lee.) |

Appendix XV

|

"The

Unfortunate Lass" sung by Norma Waterson, c. 1977. |

Appendix XVI

|

"The

Unfortunate Lad" (Everyman's Book of British Ballads" Ed. Roy Palmer.

1980.) |

Appendix XVII

|

"The Wild

Cowboy" (The Dying Cowboy) ("Folk Songs of The South" John Harrington

Cox. 1963.) |

Appendix XVIII

|

"The

Cowboy's Lament" ("Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads. John A.

Lomax. 1966.) |

Appendix XIX

|

"The Dying

Hobo" written by Bob Hughes c. early 20th century. |

Appendix XX

|

"The Dying

Hogger" (Anonymous) "A Treasure of American Ballads". |

Appendix XXI

|

"The Newry

Highwayman" ("More Irish Street Ballads" C.O. Lochlainn. 1965) |

Appendix XXII

|

"Rake and

Rambling Boy" by Gid Tanner and His Skillet Lickers. |

Appendix XXIII

|

"The Young

Girl Cut Down In Her Prime" sung by Frankie Armstrong. 1972. |

Appendix XXIV

|

"The Bad

Girl's Lament" ("Folk Songs of Canada" Eds. Edith Fulton Fowke & Richard

Johnstone. 1955.) |

Appendix XXV

|

"St. James'

Hospital" sung by Laura V. Donald ("English Folk Songs From The Southern

Appalachians Vol. II. Cecil Sharp. 1952.) |

Appendix XXVI

|

"St. James' Hospital - "Iron Head's Version" by James (Iron Head) Baker.

-/5/34. Sugerland, Texas. 1966. |

Appendix XXVII

|

"Dying

Crapshooter's Blues" by Blind Willie McTell, 1949, Atlanta, Ga.

(Atlantic). |

Notes

|

|

Bibliography

|

|

|