Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

The English Music Hall Connection |

|

The English music hall came into being in the early decades of the nineteenth century but some of its predecessors and precursors go back over three hundred years. The earliest of these, the chaunters, I will be coming back to later on. But first we will consider the more widely recognised music hall 'roots'. "Modern music hall (which can be said to date from about 1860) was an amalgam of three popular elements: the pleasure-garden with its saloon theatre, the song-and-supper room, and the catch and glee clubs and harmonic meetings of tavern concerts."(1). In 1928, a music hall performer and correspondent, Chance Newton, reported that in the earlier part of the nineteenth century (c.1828), music hall acts were to be seen in pubs or otherwise "licensed premises": "twice or thrice weekly as a rule, under the name of Free-and-Easies, or Sing-Songs."(2). By the 1850's, he adds in a rather bemused tone, "they had become known as "Select Harmonic Meetings" if you please,"(3). A definition of the Free-and-Easies is given as "Taverns and early music halls rum on casual free-and-easy lines with the customers supplying their own impromptu entertainments."(4). A variation on music hall's roots is offered by Martha Vicinus who says "The music hall came from three maim sources: the tavern free and easies, the travelling theatrical companies and the song-and-supper clubs centred in London."(5). Perhaps the most encompassing description and therefore the most accurate, included the chaunters "... music hall and variety... are the inheritors of medieval balladists, eighteenth century song-sheet sellers," as well as "Glee Clubs", "Caves of Harmony" and pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall and Cremorne"(6).

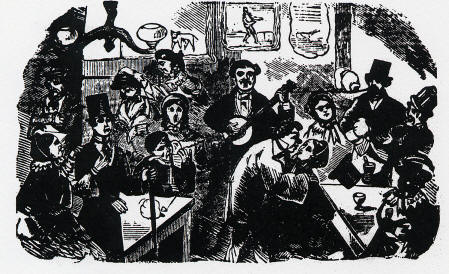

But before discussing the music hall phenomenon 'proper', I will embark on a brief journey through time to its beginnings, in the late seventeenth century, around 1684 in fact. "About this time there was introduced at the London fairs, an entertainment resembling that now given in the music halls, in which vocal and instrumental music was alternated with rope-dancing and tumbling. The shows in which these performances were given were called music-booths, though the musical element was far from predominating... "(7). These music booths were soon attacked for "their alleged demoralising influence and as licenses were not reissued for them around 1700; "...the fairs all over England began to run down."(8). With the coming of the Industrial Revolution the use of the latter "as a labour exchange (or slave market)" were made "...less necessary; moralists managed to suppress the entertainments; the public wanted something newer and more regular--it found it in music hall."(9). Of course these are generalisations and while they may depict trends and events as indicated, they do not tell the whole story. As with many socio≠historical phenomena, they are not always neatly sequential but often overlap and exist as parallels. For example, the London pleasure gardens which reappeared after the Restoration in the seventeenth century and by the eighteenth often featured the sort of entertainment later to be found in music halls. Like the latter the gardens charged an admission fee which gave the customer access, for no further outlay, to all the various types of entertainments that were available. As one overseas visitor to the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens in 1748 observed "No man or lady enters the garden without paying a shilling at the entrance. After that anyone is free to buy anything or not. One can in the meantime listen to the music, walk about, see and be seen, without any further cost."(10). The Vauxhall, along with Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens, were for the wealthier upper classes or "society". There were other less elaborate affairs for "the masses". "These pleasure gardens were usually attached to either a public house or a spa."(11). (see Fig.2.). But music halls did not start to appear in the early part of the eighteenth century as Cheshire seems to imply. "Glee Clubs" and "singing rooms" became popular in the immediate interim period. These were initially private functions with selected guests and the forerunner of the song-and-supper rooms which in turn are "...usually regarded as the most immediate ancestors of music halls"(12). The latter became the vogue at the beginning of the 1800's and co-existed for a while with the pleasure gardens. As is noted "The song-and-supper rooms and the pleasure gardens of the 1830's and '40's had been fashionable resorts for the demi-monde and the bohemian; they were for all who sought pleasure outside the narrow boundaries of Victorian respectability."(13). But the pleasure gardens perhaps inevitably, eventually suffered in popularity "...and they were closed in 1859".(14). Although some hung on until the 1870's. The song-and-supper rooms had started out as purely male preserves, but were soon to introduce a "ladies evening" so that men could take their wives/girlfriends. This was soon to be extended throughout the week and even more so when this social centre transferred to the pubs or 'beerhouses' which attracted the working-classes. Newton comments "In those days every music-hall was but the chief room or at best, a mere annex, of this or that tavern or gin palace. They were run entirely on drinks or what is usually known as "Wet Money".(15). The main factor in this transference was the "...,allurements held out to the working-classes at many of the beerhouses by means musical entertainments,"(16). Very soon as certain entertainers became more popular, many taverns started to charge entrance fees for Newton's "mere annexes". The music hall had arrived.

Other informants told Mayhew of functions and performances in. penny gaffs such as pantomimes, stage clowns, ballet, and snake swallowers! Elsewhere street traders of "eatables and drinkables" complained that the gaffs were taking their young customers away. The latter spending their money on the entrance fee reported Fig, 2: Poster for a typical tavern & tea gardens of the early 19th.c. "Singing and rather than on buns and lemonade in the streets. The only thing to be said about the penny gaffs from a "moral" point of view, is that they did not sell alcohol! The latter was available, however, at another social function-- the "twopenny hop". The hops were much favoured by the costermongers, Mayhew tells us, and the dancing was usually very exuberant, going on until sometimes 2 o'clock in the morning. "There is sometimes a good deal of drinking; ... From £1. to £7. is spent in drink at a hop." (22). Some fifty-odd years later in 1903, one of the best known music hall performers, Kate Carney, was to record an updated title (due to inflation?) celebrating "Our Threepenny Hop". A report in 1916, on Hugh Didcott, one of the most successful agents/promoters of music hall, enthused "Didcott certainly endowed music hall agency with style and commercial system, and remained throughout his life its most picturesque figure. He has taken performers from soldiers' sing-songs, from Margate sands, from Fast End music halls, from penny gaffs--"(23). The term 'music hall' as a place of popular entertainment was not in general usage until the 1850's. Up to that time they were referred to as sing-songs, concert-halls, theatres, ballet-houses, amongst other titles! But prior to all these phenomena and a direct link to the earliest music halls was the chaunter. Chaunters were literally street-singers who had been in existence for centuries and their presence in 1851 caused Mayhew to observe that this presented "...a further point of resemblance between ancient and modern street folk," (24). (see Fig.3.). The one 'recent' innovation is "The chaunter now not only sings, but fiddles,"(25). Basically, the chaunter would sell his songs by singing them in the streets. The songs were printed on one side of a sheet of paper known as broadside ballads or simply broadsides. The content of these broadsides would vary from current events at home and abroad, the latest scandal-political or otherwise, dying confessions of condemned murderers, executions, and lyrics of their own invention, amongst others. These broadsides would be sold for a penny or for whatever the ballad-maker could get! An encyclopedic definition runs "Broadside ballads also called stall ballads, a semi≠journalistic creation of Elizabethan England, had their heyday in the 16th. and the 17th. centuries."(26). Nevertheless they were "...an important way in which news was spread until about 1860."(27).

The published broadsides became so popular in the early nineteenth century that the chaunter became the 'ballad singer', as by then, his "...main chance of an income was to work for a ballad publisher."(29). One of the most famous ballad publishers was Jeremy Catnach who operated from Seven Dials near Charing Cross Road. The chaunter or ballad singer was paid for the words of his song and Catnach, who was not a musician himself, "...kept a resident fiddler on the premises to enable him to hear what was proposed."(30). But the chaunter or ballad singer was soon to become a thing of the past. With the rising popularity of the early music halls from the 1850's, the ever-widening circulation of newspapers and general urbanisation of the populace, the chaunter had to adapt or disappear. But at first the latter enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the music hall. "During the early stages of the halls, from approximately 1850 to 1875, programmes included songs from many different sources. Traditional folk elements and folk songs, borrowed from an oral culture and the broadsides were very much part of an evening's repertoire. In turn, broadside sellers hawked music-hall hits, giving credence to their claims of keeping up with the times."(31). By 1856 the writing was already on the wall, as reference by one of Mayhew's street singers to "the cheap concerts held at the public-houses"(32),; indicates. A reporter in the 'National Review' in 1861 gloated with obvious relish "The decay of the street ballad singer ... we attribute more to the establishment of such places of entertainment as Canterbury Hall and the Oxford, and the sale of penny song-books, than to the advance of education or the interference of the police... we do not pretend that they will be any great loss-"(33). The Canterbury Hall had been in existence in one form or another as a music hall since 1851 when Charles Morton, often known as 'Father of the Halls', opened it in Lambeth Marsh and introduced the then innovative idea of admitting both sexes. The Oxford was a new hall that had opened the same year as the report quoted in the 'National 'Review'. However, it would appear that from a moral point of view, if not a musical one, there was little to gloat over. For in the 1860's "The only music≠halls in existence at that period ... were of course, mere sing-songs of the low, and indeed often loathsome, "Cyder cellars" and "Coal-hole" type"(34). The latter were song-and-supper rooms of an earlier era, which had reputations as 'dens of iniquity''. Newton adds, on the brighter side: "About that time, however, there began to spring up in and around London quite a large group of what were then called "minor theatres".(35). The demise of the broadside seemed imminent some ten years later. Lee reports that "By 1871 there were only four ballad presses left--"(36). This was compared with "...seventy-five in 1800."(37).

Some of the chaunters managed to adapt and started performing in the pubs, taverns and beer halls, "first selling their songs from table to table, and then performing in front of the patrons. Those who were able to win over this audience became the first music hall artists."(38). One of the earliest music hall singers was Jenny Hill (1850-1897). She started out c.1869 in "a very ordinary pot-house sing-song in Bolt Court, Fleet Street."(39). Although she never recorded, we do have Newton's remembrance of two of her "husband-nagging, semi≠pathetic songs" which would have been imbued with a vocal not too far removed from the Blues. Certainly her words had parallels in a lot of female blues of the 1920's and '30's

and:

While Lucille Bogan from Alabama had a man who gambled as well!

Although the last verse contains a rural atmosphere, absent from most music hall songs, the theme remains the same. Ms. Bogan was one of the finest of all rural Blues singers and possessed a raw earthiness often matched by her lyrics. Another female Blues singer, in a much lighter vaudeville vein, one Lena Henry, included the following lines:

Vaguely recalling the atmosphere of Ella Shields' "Burlington Bertie from Bow" in 1915 in working-class London. Another unrecorded singer was Lottie Collins (1866-1910) who became synonymous with "Ta Ra-A-Boom-De-Ay" to which she performed the most energetic and exciting dance on the British stage at the time. This number was inspired by a black song either from St. Louis or New Orleans according to different informants. Another contemporary of Ms. Collins was Bessie Bellwood (1857-1896) who also unfortunately never recorded but was apparently as brash and on occasion 'suggestive' as Marie Lloyd, but without the latter's finesse. Nellie Powers and Miss Caulfield were other early music hall singers and were, like the majority of such artists, from the working-classes centred in and around London. Whereas the street singer/chaunter had catered almost exclusively for this social stratum, with the advent of the early music halls in the East End of London, it was soon to be enjoyed by the upper classes as well although the genre was always to be regarded as a part of British working-class culture until its generally recognised demise in 1914. The Blues of the Deep South was also of the working-classes, in black American society. It is therefore not too surprising that some of the themes were to crop up in both cultures. Not only themes but versions of the same songs, although some of these from the English music hall had been popular in the last decades of the nineteenth century, some 30 years before recording started in the world of the Blues. There are also at least two examples of songs prior to 1870 either being 'covered' by U.S. black singers in the twentieth century, or greatly influencing the lyrics of some of the earlier Blues singers. I shall be exploring these aspects more fully in chapter III; but the question of how these songs were transmitted from England to southern U.S.A. is the subject of the next chapter. Notes

1.Busby.R.p.6.

Illustrations |

Website © Copyright 2001-2008 Alan White. All Rights Reserved.

Text (this page) © Copyright 1992 Max Haymes. All Rights Reserved.

For further information please email:

alan.white@earlyblues.com

But

there were other social centres enjoyed by the working-classes at this

time, which also be included as precursors of the music hall. One of the

most prominent was the "penny gaff". Although one contemporary

description tells us that the penny gaff or "blood tub" was an

"Improvised theatre which presented lurid melodrama and thrived

in the East End of London during the nineteenth century."(17), some of

the reports collected by Henry Mayhew, give a more diverse scenario. In

the 1850's, a street trader known as "a coster lad" told him of his

dislike of going to church and "Plays, too, ain't in my line much; I'd

sooner go to a dance--it's more livelier. The "penny gaffs" is rather

more in my style; the songs are out and out, and makes our gals laugh;

The smuttier the better I thinks;"(18). Presumably in response to a

further question from Mayhew, the coster lad responds "bless you! the

gals likes it as much as we do."(19). On visiting a penny gaff for

himself, Mayhew, shocked and horrified by the obscenity of the lyrics,

dancing formed the whole of the hour's performance, and, of the two, the

singing was preferred."(20). Predominantly frequented by girls and women

from age eight up to twenty, at least one 18-year old viewed the gaffs

with similar horror. "'The first step to ruin in them places of "penny

gaffs", for they hears things there as oughtn't to be said to young

gals."(21).

But

there were other social centres enjoyed by the working-classes at this

time, which also be included as precursors of the music hall. One of the

most prominent was the "penny gaff". Although one contemporary

description tells us that the penny gaff or "blood tub" was an

"Improvised theatre which presented lurid melodrama and thrived

in the East End of London during the nineteenth century."(17), some of

the reports collected by Henry Mayhew, give a more diverse scenario. In

the 1850's, a street trader known as "a coster lad" told him of his

dislike of going to church and "Plays, too, ain't in my line much; I'd

sooner go to a dance--it's more livelier. The "penny gaffs" is rather

more in my style; the songs are out and out, and makes our gals laugh;

The smuttier the better I thinks;"(18). Presumably in response to a

further question from Mayhew, the coster lad responds "bless you! the

gals likes it as much as we do."(19). On visiting a penny gaff for

himself, Mayhew, shocked and horrified by the obscenity of the lyrics,

dancing formed the whole of the hour's performance, and, of the two, the

singing was preferred."(20). Predominantly frequented by girls and women

from age eight up to twenty, at least one 18-year old viewed the gaffs

with similar horror. "'The first step to ruin in them places of "penny

gaffs", for they hears things there as oughtn't to be said to young

gals."(21). As I have

already stated the broadsides were printed. With the advent of printing

presses, some enterprising individuals saw a market by having the

chaunters sing the song to them, using any traditional tune that would

fit and then having the chaunters sell them in the streets on

'broadsheets'. "Chaunters sang and sold their songs on street corners,

at factory gates, on country fair≠grounds, in markets, at prize-fights,

on racecourses, at executions, anywhere a crowd might gather."(28).

These 19th. century chaunters or street singers would appear to follow

similar 'circuits' to the Blues singers in the 20th century. The latter

would play in barbershops, on train stations, in the street

intersections (like the famous one at Fourth and Beale Streets, in

Memphis), and some singers like Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Willie McTell

would perform at drive-in movie shows and outside the tobacco factories

on pay-day, in Durham, North Carolina in the 1930's.

As I have

already stated the broadsides were printed. With the advent of printing

presses, some enterprising individuals saw a market by having the

chaunters sing the song to them, using any traditional tune that would

fit and then having the chaunters sell them in the streets on

'broadsheets'. "Chaunters sang and sold their songs on street corners,

at factory gates, on country fair≠grounds, in markets, at prize-fights,

on racecourses, at executions, anywhere a crowd might gather."(28).

These 19th. century chaunters or street singers would appear to follow

similar 'circuits' to the Blues singers in the 20th century. The latter

would play in barbershops, on train stations, in the street

intersections (like the famous one at Fourth and Beale Streets, in

Memphis), and some singers like Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Willie McTell

would perform at drive-in movie shows and outside the tobacco factories

on pay-day, in Durham, North Carolina in the 1930's.