Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

I Need-A Plenty Grease In My Frying Pan |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

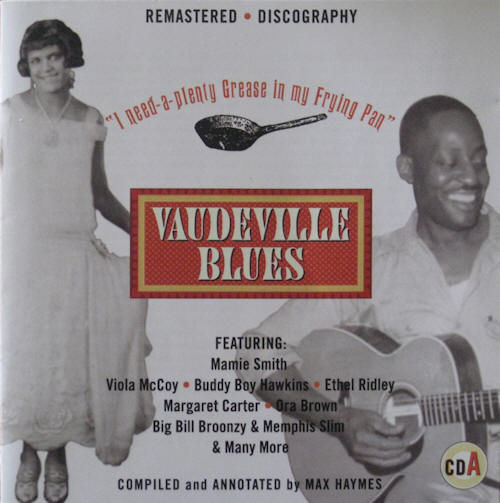

CD A - Who Toot Your Fruttie Nice An' Tight? At first glance the title of this 4-CD set might lead readers into thinking they are about to take yet another dip into the world of culinary delights - they might! But the menu presented here for JSP Records is one for the soul and mind. Sometimes intriguing, sometimes harsh or a little sweet and liberally garnished with red hot spicy bits! As a taster (pun intended!) the initial two songs are featured by a very fine singer Margaret Carter, and indeed consist of her entire recorded output.

Then comes an instrumental break led by some sizzling(!) - if brief - cornet and trombone from an unidentified musician and Charlie Irvis, respectively.

The driving accompaniment on Come Get Me Papa Before I Faint [Pathe Actuelle 7511] fires up Ms. Carter to get her man told as he seems to spend way too much time away from home.

And he had better listen up, because she ain’t! ‘Ah! Play that thing, Big Charlie’ she shouts to Irvis in the break. Although the excellent notes are by David Evans, the legend for Margaret Carter reads in the discographical details (presumably not by Evans) “prob. Margaret Johnson”, (3) in 1996. No other writers seem to have picked up on this. I personally am not so sure if their vocals aren’t a bit similar. Especially on Margaret Johnson’s Mama, Papa Don’t Wanna Come Back Home [OKeh 8405] in the same year of 1926, but a couple of months after Carter’s disc. This similarity is less obvious in 1925 when Johnson adds to our culinary ‘theme’ with a Sidney Bechet number Who’ll Chop Your Suey (When I’m Gone) [OKeh 8193] This included the probing enquiries:

Margaret Johnson is in the upper echelons of vaudeville blues singers. But the jury is still out on whether she and Margaret Carter are one and the same. Despite details given by Eugene Chadbourne on the net at allmusic.com/artist earlier in September, 2011. I am waiting for the source of this info before being convinced. Unfortunately, Johnson is only a little less obscure. She does not appear in either of the Blues Who’s Who works. And Tony Russell noted that for her “Appearances on the vaudeville circuit are logged from 1922 to 1932 but nothing is known of her subsequent life”. (5) Russell could have added or her earlier life either. So here in 2011 the uncertainty remains - details pending - as to whether their being only one person involved here or not. But I’m jumping ahead of the story! From the Blues rural beginnings in the last decade or so of the 19th. Century, swiftly followed an early urbanized form formerly known as the ‘classic blues’. This term was favoured by nearly all the jazz pundits writing in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. But this title did not accurately describe the wide range of the recordings which covered some truly classic sides right through to items more at home on the music hall and vaudeville stage. An early champion of the genre was British jazz enthusiast/historian/author the late Derrick Stewart-Baxter who was way ahead of his time. “Never was a description more displaced than the term ‘Classic Blues’. They were never Classic in the true meaning of the word, nor were they always blues. The virtues that the style possessed were many and ranged over a large variety of singers ... but it must be admitted it was a hybrid form - like jazz itself - stemming from such sources as the rural blues of the Deep South, tent show songs, and the vaudeville and music hall performers of the early ‘twenties (and even earlier), ragtime and jazz. Most important of all was vaudeville. It would be no exaggeration to say that every so-called Classic singer showed, to a greater or lesser degree, the debt she owed to the music hall and cabaret. (6) Baxter quotes celebrated jazz singer George Melley (also deceased) in his book from which the L.P. was named. In a more incisive tone, Melley who was an avid fan of vaudeville blues was one of the earliest to use this term: “In the vaudeville blues there is a proportion of the worthless, the mechanical, the contrived, but there is also a gaiety, a vitality, a sense of good time.” (7) [Footnote 1: See also the ‘set’ introduction by David Evans and his informative notes to a series of obscurer vaudeville singers on Document Records (Female Blues Singers Vol. 1-14) without which this project would not have been possible.] So by the 1990s this early urban style (itself rooted in minstrelsy from the early 19th century onwards) became popularly known by its more appropriate heading ‘vaudeville-blues’ (the hyphen is optional!). Its peak of popularity ran from 1920 until the middle of the decade. Thereafter, only a handful of the best artists continued making records, before the general eclipse of vaudeville blues by the 1930s and the onslaught of the Great Depression. [Footnote 2: Although some of these early singers did make recordings in the post-war period and on into the early 1980s. Most notably: Alberta Hunter, Ida Cox, Edith Wilson, Sippie Wallace, Victoria Spivey, Lucille Hegamin and Hannah Sylvester. Check the internet for availability.] This genre was almost exclusively dominated by female singers although a few men did get on record. But with the glaring exception of the very popular banjo/guitarist Papa Charlie Jackson, they sank almost without trace. Although there were a mere handful who did gain some recognition via the popularity of husband and wife duos. Most famously Jody Edwards in Butterbeans & Susie, Kid ‘Sox’ Wilson in Coot Grant & Kid Wilson, and George Williams with Bessie Brown; being among the more successful such acts. (see CD 4) Black female singers in the first decades of the 20th. Century - during which time the Blues had ‘arrived’ - were generally part of their community at the lowest rung on the socio-economic ladder. I am here, talking about the vast majority of black women and the female blues singers in particular, who sang and recorded the first blues on records; formerly ‘the classic blues’ and more correctly now the ‘vaudeville blues’. Indeed, from 1920 until the end of 1925, these singers almost completely dominated the Blues scene. This CD set is an attempt to do a survey of some of these artists and explore their influences from and to earlier styles going back to the 1900s. Throughout these 4 CDs will be included examples of a rural blues which has some stylistic links - be it lyrics or music - to its vaudeville blues counterpart, or vice-versa. [Footnote 3:See Railroadin’ Some (railroads in the early blues). Chapter 9: Gonna leave the Pullman an’ ride the L & N. p.p. 273-296. Max Haymes. Music Mentor Books. York. 2006. Also available online] As in the fairly well-known case of the Ma Rainey and Charley Patton Booze And Blues/Tom Rushen Blues connection. (see CD 3) The above paragraph includes the remarkable fact (in musical genres) that the vaudeville blues singers recorded an urbanized later development of the original rural styles which had surfaced in the closing decades of the 19th. Century. These ‘country’, ’rural’, or ‘downhome’ blues were mostly sung by men and often with a lone instrument; the guitar, harmonica, piano, [Footnote 4: Of course, many vaudeville blues singers were accompanied by a single instrument which was usually a piano generally in a more urbanized style; more rarely a guitar or a ukulele/banjo were substituted or added.] or with no accompaniment at all. Sometimes other performers were augmented on mandolin, banjo, fiddle, or a second guitar. Yet it was not these earlier ‘original’ blues that made it on a record first - as already noted. Further to this, the female rural counterpart, providing their own accompaniment on record is sparse to say the least. Even though many more probably remained unknown lurking in the shadows of time. Two notable exceptions who recorded more prolifically were Memphis Minnie (see JSP 7716 & JSP 7741) and Moanin’ Bernice Edwards, (JSP 7723-A) playing guitar and piano, respectively. There were others of course, who left but a handful of sides as their recorded legacy. Louise Johnson, (JSP 7702-D,E) was a pianist from Mississippi; Geeshie Wiley and Mattie Delaney, (JSP 7761-A,B,C,D) guitarists from the same state. Apart from musicians, there were several outstanding singers who left a larger repertoire behind for posterity; including Bessie Tucker and Lucille Bogan. The ‘Big Four’ names in vaudeville blues are Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Clara Smith [Footnote 5: None of the various singers named Smith who got on record were related.] and Ida Cox. Ma Rainey - ‘Mother of the Blues’ (see JSP 7793-5 x CD), and Ida Cox were both from Georgia. Bessie from Tennessee and Clara hailed from South Carolina. All of these singers started recording in the year of 1923. As Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith are already well represented on JSP, only a very few of their blues will appear on this 4 CD set. Yet within the first 3 years of recorded vaudeville blues (1920-1922) well-known verses and themes from the rural blues had been featured by a variety of these earlier singers on wax. Bearing in mind that the Big Four had all cut their ‘blues teeth’ many years prior to 1920. Ma Rainey famously coming across the Blues in Missouri during a tour in 1902. Indeed, the earliest example appeared when Mamie Smith made her historic Crazy Blues [OKeh 4169] in August, 1920, when she sang:

Within a month Ora Brown (see JSP 77141-Meaning In The Blues) put down a unique verse on one of her only two 78 recordings in her Twe Twa Twa Blues [Paramount 2481] with Tiny Parham on piano.

Though B & G R list ‘circa’ for the two dates of these recordings (April and May) they may in fact have been recorded around the same time. But both Brown and Hawkins are almost bound to have heard Bessie Smith ‘Empress of the Blues’ and her Sorrowful Blues [Columbia 14020-D] recorded on 4th. April in 1924, which commences with the ‘twee twa twa’ scat vocal. Indeed, the very first recording using this scat phrase appears in That Twa Twa Tune [OKeh 8118] by Esther Bigeou at the beginning of December, 1923. She tells the listener that it is something new “and I will introduce it to you …

Ms. Smith may well have seen Bigeou at a show or at least heard her recording. The scat vocal goes back to some of the earliest vaudeville blues and prior to the Louis Armstrong ‘accident’ on his Heebie Jeebies session! One example comes from 1923 via Ethel Ridley’s Memphis Tennessee [Victor 19111], made some 6 months prior to the song by Esther Bigeou. A much later entry into vaudeville blues was another singer who shared the same Christian name as Ora Brown - Ora Alexander. Commencing in 1931, she seems to have come straight from the raucous scenario of the barrelhouse with her roaring scat vocals through a total of 8 sides between 1931 and 1932. Encouraged by unidentified shouts from her accompanists, one of whom was possibly James P. Johnson, the very rural sounding You’ve Got To Save That Thing [Columbia 14607] also has more than a smack of hokum blues then currently doing the rounds in the black section of cities such as Chicago, Detroit, New York, etc. And on this occasion it is very likely to have been influenced by the more rural jug band sounds in Memphis particularly, from the 1920s. In 1930, the year before Ora Alexander’s debut, the superb Jed Davenport and his Beale Street Jug Band (see JSP 7752-C) fairly rock through Save Me Some [Vocalion 1513] with what has to be the finest jug solo on a record and cracking harp from Davenport to boot! Unlike Ora Alexander, Jed Davenport concentrates not on sex but on his hard-earned money that his wife takes - and booze!

Returning to the Ora Brown disc, a couple more verses were among the first to appear utilizing the phrase “good morning blues” on record [Footnote 6: See also Luella Miller for a slightly earlier link on her Down The Alley in January, 1927.] and may also have been a precursor of a Big Bill Broonzy recording in the early 1940s.

This personalizing of the blues is a current that runs through the earlier genre and former excellent rural blues singer, Big Bill Broonzy, (see JSP 7718, 7750, & 7767) now in a more urban style of pre-electric Chicago blues in 1941; extends Ms. Brown’s imagery.

The mythological [Mr.] ‘Blues’ who is everywhere and not just a state of mind. Like Ora Brown, Bill puts the blame for everything on ‘his’ shoulders. They make him “drink an’ gamble an’ stay out all night, too” (16) The singer even accuses ‘Blues’ of being drunk! Finally, he implores with the entity to help him live rather than attempting to kill him.

Lucille Bogan, mentioned earlier, is almost unique in commencing her career as a vaudeville blues singer in 1923 and soon gravitating to becoming one of the raunchiest blues artists who I feel belongs in the rural blues idiom. (see 3 trax included on JSP 77141- Meaning In The Blues) Having said that, Ms. Bogan was only a competent vaudeville singer. As Guido van Rijn and Hans Vergeer put it in the 1970s: “Lucille’s voice was still immature in comparison with the full voice we know from her later recordings … Lucille is probably the only female singer to have switched from ‘classic blues’ to ‘country blues’. (18) From the second session in June, 1927, Bogan’s Kind Stella Blues [Paramount 12504] illustrates admirably the foregoing comments. With the advent of the electrical recording process in the mid-1920s, Lucille Bogan’s performance fairly leaps out of the grooves superbly backed by barrelhouse pianist Will Ezell. This song, along with parts of her Levee Blues [Paramount 12459] from the previous session in March, was the basis of the equally superb Gamblin’ Charley [Columbia 14420-D] by country bluesman Charley Lincoln which is included on the 4x CD set Meaning In The Blues on JSP. Lucille Bogan (1897-1948) originally from Amory, Mississippi, soon re-located in or near Birmingham, Alabama. [Footnote 7: I maintain Lucille Bogan lived in Fairfield, a suburb of Birmingham some 3 or 4 miles from the city centre or ‘downtown’. See Railroadin’ Some. Ibid.] In early June of 1923, OKeh Records visited Atlanta in Georgia to make what were then the first field recordings of a blues singer. Or as Guido and Hans wrote: “She was the first black blues artist to record on location, i.e. outside Chicago or New York.” (19) The term ‘field recording’ usually extended to any sessions made in the South generally. Okeh also recorded other black artists on this visit (as well as white hillbilly musicians - famously the debut of Fiddlin’ John Carson). These were the Morehouse College Quartet who were an a capella group who cut three sides-their total output - of gospel material and another vaudeville blues singer Fanny May Goosby (CD 2) with one title, which OKeh issued on the flipside of the Bogan tune The Pawn Shop Blues [OKeh 8071] (20)

In 1929 the King of the Delta blues Charley Patton (see JSP 7702) utilized Hunter’s 2nd. verse spreading it into 2 of his own on his inimitable Pea Vine Blues [Paramount 12877] at his first recording session.

He then borrowed Ms. Hunter’s 3rd. verse for his equally awesome Magnolia Blues [Paramount 12943]. Omitting of course the verb to ‘chirp’! Actually an alternate take of his When Your Way Gets Dark [Paramount 12998] and probably his most ethereal piece on a record. The guitar sings (…) as was part of the early blues tradition.

Alberta Hunter was an extremely popular and very successful vaudeville blues singer as well as appearing in many theatre shows during her long career and Charley Patton would have had many an opportunity to hear her recordings. Like Robert Johnson and Blind Willie McTell he listened to earlier blues records. As one of his contemporaries, Booker Miller, recalled to author Gayle Wardlow in the late 1960s: “He listened to records. I’ll tell you one he kinda liked pretty good, but he never did try to play it. Leroy Carr put out a record, I think it was about in ’twenty-nine; it was Prison Bound. Now he liked it.” ( 25) The authors noted that “In the 1920s it became possible for blues entertainers to reach audiences they never saw, via the phonograph … [it] was to create its own generation of blues stars. It would impress Patton with a sense of his own insignificance: even after he became a celebrity in his own right through recording, Booker Miller recalled, he continued to look up to the likes of Blind Lemon Jefferson and Leroy Carr as ‘big shots’” (26) Although Calt and Wardlow pointed out how “Patton’s own repertoire had been enriched by records” (27) by earlier vaudeville blues releases featuring Ma Rainey (CDs 2 & 3), Ardelle (Shelly) Bragg, and Hound Head Henry (CD 3); Booker Miller - a fellow Delta guitarist - failed to mention any artists from this earlier period. As a protégé of Patton and half his age it is entirely likely Miller was unaware of the earlier blues women apart from Bessie Smith. (CD 1) However, Alberta Hunter’s recording which had helped shape two of Charley Patton’s finest songs was covered as I noted by several other singers and Chirpin’ The Blues was nearly as popular as her Downhearted Blues [Paramount 12005]. Table 1

Viola McCoy, along with Alberta Hunter, is the only singer to cut more than one version. Her initial one has Porter Grainger in unusually more ‘bluesy’ form and Viola says in the break “Oh! Don’t play it so lonesome Mr. Piano Man.” (28) In the remake a month later (included here) she replaces this with some low-down kazoo. She sings in a lower register than any other of these singers on Chirpin’ and Bob Rickett’s bouncing piano help make this one of the definitive recordings of this song. But the top spot has to be Alberta’s who’s song it was. [Footnote 9: Although also credited to pianist/bandleader Lovie Austin as a co-writer for many years, see Ms. Austin’s denial quote in Alberta-A Celebration In Blues. p.65. Frank C. Taylor with Gerald Cook. [McGraw-Hill Book Company. New York. St. Louis. San Francisco. Toronto. Hamburg. Mexico.] 1987. ] Fletcher Henderson acquits himself admirably here, “Play that thing, boy.” (29) Alberta calls to him. Mary Straine who may have actually recorded Chirpin’ The Blues before Viola McCoy in April, 1923, includes a couple of different verses. One which runs:

About 12 years later Charlie Manson who took part of Bessie’s earlier recording as his title cut Nineteen Women Blues [ARC unissued].

But to return to the earliest era of vaudeville blues (1920-1922) I have already referred to. Following her massive hit ‘Crazy Blues’, Mamie Smith was in the OKeh recording studios again in September, 1920; and made Fare Thee Honey Blues [OKeh 4194] with her Jazz Hounds. This song aired some traditional/rural verses on wax for the first time. Two of which ran:

[Footnote 10: For more detailed discussion on this verse, check out Railroadin’ Some. Ibid. p.p.35-36.] The initial verse appeared on various subsequent blues recordings, most famously on Robert Johnson’s Walkin’ Blues [Vocalion 03601] with a slight adaptation in the first line.

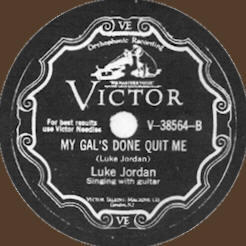

The second verse from the Mamie Smith recording was also fairly popular with both male and female singers; including a 1923 outing from Ethel Ridley (CD 1) on Alabama Bound Blues [Columbia A 3965] and in her Goodbye Rider [Victor V-8030] by tough Texas rural singer, Ida Mae Mack. From Lynchburg, Virginia, Luke Jordan included it on his My Gal’s Done Quit Me [Victor V 38564] in 1929. Robert Johnson’s Walkin’ Blues also featured a version of a verse from Luella Miller’s Frisco Blues [Vocalion 1202] from 1928. Presumed to be from the St. Louis area, she has a much more harder vocal approach in her phraseology and timing. Also implies a more than casual knowledge and use of railroads than most of her vaudeville blues contemporaries. She comes across as much more a rural singer. Though one writer noted: “Her music … falls outside of both Delta [aka rural] and urban styles.” (35) Here she takes the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway (the Frisco) to task by taking her man away.

Luella

Miller then introduces a verse that was only to appear (albeit in

slightly altered lyrics) on 3 other blues recordings- Walkin’ Blues

[Paramount unissued] by Son House and the same title by Robert Johnson,

but a different song;

[Footnote 12: Several blues titled Walkin(g)

Blues were made prior to Johnson’s, including one by Ma Rainey in

December, 1923. But they are different songs. With the exception

of the Son House side from 1930 (See JSP 7715 - Legends of Country

Blues) which inspired Johnson

for lyrics and House’s 2-part My Black Mama which gave impetus

to the musical structure of the later piece.]

Intriguingly, Luella Miller recorded a Frisco Smoke Blues at her previous session in 1928 on 24th. January, but remained unissued by Vocalion Records.

Mamie Smith was quickly joined by other singers on various record labels. Her commercial success had triggered off a veritable flood of releases, including songs by Mary Stafford, Edith Wilson, and Lucille Hegamin (more on these artists later). One of the most outstanding was Alberta Hunter whom we have already ‘met’. She started recording in May, 1921. Her second take of He’s A Darn Good Man (To Have Hanging ‘Round) [Black Swan 2019], contained a line that was soon to become part of a floating verse among rural blues singers. Although the opening line appears unique to Alberta - if she does indeed sing ‘Worcester brown’!

Willie Brown’s Future Blues [Paramount 13090] is but one example as part of what is a superb blues, to boot. (See JSP 7702-D)

__________________________________________________________________________ Notes:

__________________________________________________________________________ © Copyright 2012 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This

is undoubtedly Ms. Straine’s idea as these lines do not appear on any

other versions. Although she may well have got it from hearing

variations of the verse from unrecorded rural singers (at the time).

Ones that later got on disc include blues by Daddy Stovepipe, (see

JSP 7798A-) in 1924 on his Sundown Blues [Gennett 5459]. It

was now ‘19 women’ and presumably remained so when recorded by Stovepipe

No.1 some 3 months later, with a re-make in 1927. Sadly, both of these

latter tracks remain unissued. But as already noted, (in April, 1924)

the ‘Empress of the Blues’ Bessie Smith, a good month prior to Daddy

Stovepipe, cut her Sorrowful Blues [Columbia 14020-D] with

fiddler Robby Robbins lending as downhome a sound as ever appeared on a

Bessie Smith recording. Co-written by the singer and Irving Johns who

is absent from the piano stool, and probably took care of the musical

score while Bessie supplied the words.

This

is undoubtedly Ms. Straine’s idea as these lines do not appear on any

other versions. Although she may well have got it from hearing

variations of the verse from unrecorded rural singers (at the time).

Ones that later got on disc include blues by Daddy Stovepipe, (see

JSP 7798A-) in 1924 on his Sundown Blues [Gennett 5459]. It

was now ‘19 women’ and presumably remained so when recorded by Stovepipe

No.1 some 3 months later, with a re-make in 1927. Sadly, both of these

latter tracks remain unissued. But as already noted, (in April, 1924)

the ‘Empress of the Blues’ Bessie Smith, a good month prior to Daddy

Stovepipe, cut her Sorrowful Blues [Columbia 14020-D] with

fiddler Robby Robbins lending as downhome a sound as ever appeared on a

Bessie Smith recording. Co-written by the singer and Irving Johns who

is absent from the piano stool, and probably took care of the musical

score while Bessie supplied the words.