Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Early Blues Interview

|

|

When Austin, Texas, based blues mainstays Omar & The Howlers hit the stage, they astonish audiences with the band's bone-rattling display of swinging, rocking blues and swampy R&B. Highlighting the smouldering guitar attack and gravelly, gutbucket vocals of leader Omar Dykes, The Howlers' play their infectious brand of Texas-by-way-of-Mississippi blues and roots rock for a devoted legion of fans all around the world.

"His

guitar slices like a freight train pulling a load of Texas tone ... and

his voice has the kind of delivery that could shatter a beer stein. Omar

& The Howlers pack a potent mojo that's dang near irresistible."

I caught up with Omar after his set at the 21st Colne Rhythm & Blues Festival, Colne, Lancashire in August 2010. Alan: What were your first music memories growing up in McComb, Mississippi? Omar: In McComb music was always present. I didnít really know why and I couldnít tell you blues from pop music when I was a kid, I didn't know any difference. But there was a lot of blues where I was from and McComb is on the Illinois Central Railroad so a lot of the people who lived there would go up on the train and live in Chicago for a year or two.

Theyíd go up with an acoustic guitar and theyíd come back with an electric that had 4 pick-ups on it. All the bands in McComb were electric blues bands and I didnít identify that because when you are a kid you just think that everywhere in the world is like the place where you are at. But it got into my blood real early and I identified later that I was playing blues. Of course, where I was from everybody played everything. Black men played country music, white men played blues. Everybody mixed it up and you got to the point where you could play everything and that was kinda fun. Thatís my memory of being 7 years old and getting a guitar. I wasnít really all that interested in it, and I didnít really do much on it so my Dad sold it. When I got to about 11, I really wanted a guitar then and I told my Dad and said, ďWell you had one and I could hardly get you to play itĒ. So I wailed, ďBut if I had one now, Iíd play it!Ē. And it was true, so he got me an acoustic guitar for Christmas and I was ready then. I couldnít put it down. Alan: Were you still in McComb then? Omar: Yes, I was there until 1972 and then I moved to Jackson, Mississippi and then to Hattiesburg, Mississippi and then to Austin, Texas.

Omar: Well, the band was called The Howlers, it werenít called Omar and the Howlers, that was a different band. We wanted to move somewhere and play and we were scared to death of New York, scared of Los Angeles, didnít fit in in Nashville so we came out to Austin. The premier music in Austin was called Outlaw music, you know like the wheeling and wailing and stuff but they had a really great sub-culture that was blues and the blues sub-culture was what we were drawn to. We moved up and played a couple of years and that band dissolved but I kept the name 'The Howlers' and put my name with it, and that was the start of 'Omar and the Howlers' in 1978. The Howlers started in 1972 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Alan: How did you get the name Omar Ė where did that come from? Omar: We used to be a party band, drink whiskey, play crazy stuff, wear funny outfits and they called me 'Omar Overtone' so I had a Gibson guitar and Iíd play all the speedback stuff, fall on my back drunk so they called me 'Omar Overtone' and my wife got me a guitar strap for Christmas that said 'Omar' and it just stuck. So now if somebody calls me by Kent Dykes, my real name, I donít even hear it. Alan: You used to hang out in the juke joints at a very early age to soak up the music. Wasnít that risky at that time? Omar: No, everybody did it. That was the name of the game where I was from. You hung out where all the music was. It wasnít until the civil rights movement of í62 or í63 that it got to where I couldnít go to the black parts of town and hang out. But before then, everybody did. Alan: Music transcends, doesn't it. Omar: Yes, music transcended all of that and being from south Mississippi as well ... a lot of the stuff that happened in Mississippi got a bad rep because of press. All the black people and white people actually got on great actually. But all the tension and stuff, and the civil rights workers and people coming down trying to change things instantly made it blow up. And thatís a big myth about the south, you know we all act like we were slave owners. Some of my best friends were black and we got along great but when you got somebody trying to force something in that quick and that hard .... and something that a lot people just didnít understand is that where I was from a lot of the older black people wanted segregation too. They wanted their own clubs and their own restaurants and stuff, and we never hear anything about that, ever.

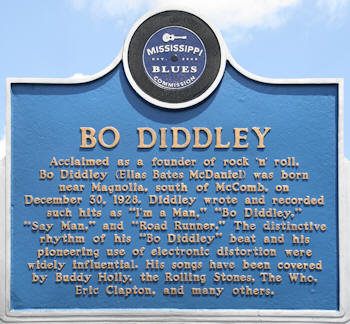

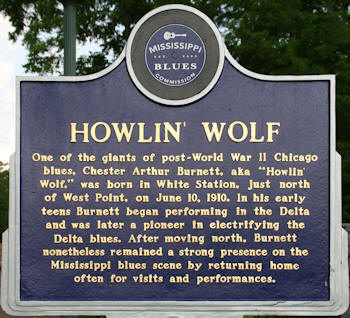

Omar: Well you know who is from McComb? Me, Bo Diddley, Snoop Dogg, Britney Spears. Britney Spears is from Kentwood Louisiana, about 17 miles from McComb; she went to a private school in McComb. Iím gonna make a Bo Diddley tribute record and get Snoop Dogg and Britney along! I'll bet Snoop Dogg would like Bo Diddley. Alan: When you started in Austin there were a lot of other bands there Ė Fabulous Thunderbirds, Jimmy Vaughan.... Omar: Oh yes, Stevie and Jimmy, W C Clark... They were all in and out of Austin. Alan: Is 6th Street the main street up there? Omar: Well, 6th Street is the party street where college kids go and get drunk. 6th street when I moved there in í76 was a dangerous place with pawn shops, black blues clubs and Mexican clubs. So when I knew 6th Street back then it was a different thing. Back in í79 the City bought up a lot of it and made it a tourist attraction. It wasnít a tourist attraction when I was there! Alan: Who has influence you the most in your music writing and playing? Omar: That is a horror question because there have been so many. Iím a Bo Diddley freak, then youíve got Jimmy Read, Eddie Taylor, Hound Dog Taylor, Carl Perkins... Iíve just been a sponge for music. And Iíve got to play with a lot of these people, like Carl. I never got to play with Jimmy Read but Iíd have liked to. Howlin Wolf I like a lot ... Muddy, Elmore James, I can get you a long piece of paper. Iíve been playing music so long that different parts of your life you dedicate to people. I couldnít listen to anything but Bo Diddley for 5 years. Itís almost like you go to college for music because thereís been so many times when Iíve got on one artist and I just couldnít get enough of it. And I think it was a study without even knowing it, you know. Alan: Your album, Boogie Man, was mainly a collateral with your friends I believe?

Alan: Are there any particular songs that you play that have special meaning to you? Omar: I play a song called Tears Like Rain that I wrote and at the time I wrote it, it meant something different to what it does now. My wife passed away in 2004 from cancer and she loved that song, but every time I play, itís impossible to play without thinking about her. So now the tears like rain are tears for her. So I choke up a little bit every time I play that song. I want to play it because itís a memorial to her, but itís hard. Alan: I know that you tour extensively Ė do you still enjoy it. Omar: I enjoy playing but I donít enjoy travelling. Youíd be hard pressed to find anybody thatís done more miles than me. Iíve been on every airplane, every bus, every train, and I used to love travelling but Iíve had enough. When Iím on stage I love it but I donít always love getting there. Alan: Itís getting harder to travel these days. Omar: It is getting harder and Iím older. Iím 60 and Iím still a tough guy but not as tough as I used to be. We used to drink whisky and chase women and stay up all night and still play, but those days are gone. Alan: How healthy do you think the blues scene is in the UK and Europe compared to the US?

Alan: We have a lot to thank the researchers for. Omar: Clapton found those first two records and he saw the significance of it. There were old blues guys all over the place I could have gone and talked to, but like I say I didnít really know what blues was. I didnít know blues from anything else and just thought that music was music. Alan: And it was just on your doorstep down there in Mississippi too. Omar: Well, it was so close I couldnít see it. Whereís the blues? I canít see it. Alan: Back in the 60s we had the British Blues Revival and we were just desperate to hear some blues but we just couldnít get hold of it. There's been a great migration of people going over to Mississippi to see the places. I went to Avalon recently to hunt out John Hurtís place. I pulled up and saw this shack and got chatting to this old guy and he was saying ďOh yes, John Hurt, he ran the farm up the road and heíd come here on a Saturday and play his guitar on the porch.Ē Omar: Yeah, I think that's what Neil was talking about; I just love Jimmy Reed but if you see his house itís a one room apartment in Chicago that didn't have any heat!

Alan: Some music styles may be fads but the blues is always with us. Why do you think that is? Omar: I think the blues is the foundation of all the modern music people like. You canít have rock music without blues. You got people like Clapton, and one of my heroes is Roy Buchanan who always told me that his stuff was based on the blues. Itís just like building a house and the blues is the foundation. People who come from different places play their stuff. Somebody was talking about reggae and I thought I hated reggae but then I played in Alabama with Peter Tosh and his band and I decided I liked reggae, because they were so good at it. That was their blues Ė thatís what they were good at. Alan: How do you see the future of blues music, do you see it changing? Omar: Well Iím amazed that itís 2010 and thereís still festivals like this British Colne Rhythm & Blues Festival. Thank God people are still here. I donít think itíll ever be the big thing but I think itíll always be bubbling under the surface and if you want to play it and hear it there will always hopefully be somewhere you can go. Europeans have done a lot to keep it going, more than the Americans. The Americans ruined it by making it into a circus like Beale Street. People who go to Memphis donít go to hear blues, they go there to buy t-shirts and salt n' pepper shakers. And if you ask what they heard, they donít know. If I was there I'd want to hear music, I got salt n' pepper shakers already. I think that's kind of a shame. But at the same time I say that, if those people hadnít done that in America then it probably wouldnít exist at all. Alan: Iím happy to see the Mississippi Blues Markers that they are putting out now to recognise where the old blues men came from. Omar: They do recognise it and I'm glad they do that, but what happens if you start promoting blues in America is that people get a bit interested then they go and buy some buses and have a bus tour and next thing you know theyíve closed the streets off and have beer on the streets and you buy a bracelet, and then you hear, ďCome to the blues circus and see pictures of some guys who have been dead for 80 yearsĒ. Well, why donít they promote some of the guys who are alive now? You know I love the ancestry of it more than anybody but they could promote the guys now instead of just talking about how great everybody used to be. Those guys would have wanted to keep going with all of us playing. Alan: What do you think of Colne? Have you enjoyed the festival? Omar: Oh yeah! I liked it last time and I loved it this time. That theatre we played in was just beautiful. It reminded me of playing back in the 60s. I like it a lot. Alan: Itís a good festival and the organisers do really well. Omar: Iím really pleased that there are people like them who care enough to do this. See, they are promoting it Ė thank God.

Alan: So, what about the future for yourself? Touring? Omar: Oh, Iím winding down my career a little bit now. Iíve had a great time playing but I canít see me really travelling now like Iíve been travelling for the last 30 years. I wonít quit, I'd like to do special gigs, but I donít want to just be out on the road all the time looking for a job. Iíve been an itinerant blues man for 30 to 40 years and Iíve been everywhere and done everything and I ainít got anything to prove. I want to do a Bo Diddley tribute record, I want to do a Howlin' Wolf tribute record and people go, ďWhy do you just want to do tribute records?Ē but itís because Iíve done everything else and I just want to play the stuff I want to play and do what I do. Iím 60 years old and itís time for me to do what I want to do. Alan: That's what I'm doing now. I've actually retired and I'm doing what I want to do.

Alan: Thank you very much Omar. I very much appreciate it.

Omar: Thanks Alan,

that's a lot of fun, man.

Album available from Ruf Records:

Return to

Blues Interviews List |

Alan:

What made you move to Texas?

Alan:

What made you move to Texas? Alan: Iíve toured

the South quite a lot and visited McComb. I was there when they

announced that Bo Diddley had died and that was quite freaky.

Alan: Iíve toured

the South quite a lot and visited McComb. I was there when they

announced that Bo Diddley had died and that was quite freaky. Omar:

Boogie Man was a lot of my song-writer buddies from Austin. All

kinds of different types of musicians. They were all my friends so I

said, ďLetís get together and weíll write a songĒ and Iím gonna make a

record and put all these songs on it. That was a lot of fun

Omar:

Boogie Man was a lot of my song-writer buddies from Austin. All

kinds of different types of musicians. They were all my friends so I

said, ďLetís get together and weíll write a songĒ and Iím gonna make a

record and put all these songs on it. That was a lot of fun Omar:

Itís different. I think Europeans view blues differently to Americans

you know. I know a hell of a lot of European friends used to come over

back in the Ď70s and they thought thereíd be people playing resonator

guitars under trees, and they were saying, ďWhere is it??Ē. And a lot

of people fly into Memphis and they go down Beale Street and they think

theyíve seen the blues. But thatís tourist crap, and you see what

commercial entrepreneurs present as the blues a lot of times. The real

blues is the guy sitting on the porch with the harmonica and the guitar

playing because they love it, playing for their friends, you know. But

Europeans ... I talked to Neil Slaven quite extensively years ago and he

was telling me how the blues to him was different, almost like a fantasy

world you know, of blues people that were like cartoon people, like

there was a comic strip of Robert Johnson, you know what I mean. He

said itís hard to visualise that all these people you grew up with are

real people and they had lives. Music was just part of their life. You

think, somebody like Robert Johnson, itís just all music but he had

relatives and he hung out with his friends. When I was a kid, about 14,

I went to

Omar:

Itís different. I think Europeans view blues differently to Americans

you know. I know a hell of a lot of European friends used to come over

back in the Ď70s and they thought thereíd be people playing resonator

guitars under trees, and they were saying, ďWhere is it??Ē. And a lot

of people fly into Memphis and they go down Beale Street and they think

theyíve seen the blues. But thatís tourist crap, and you see what

commercial entrepreneurs present as the blues a lot of times. The real

blues is the guy sitting on the porch with the harmonica and the guitar

playing because they love it, playing for their friends, you know. But

Europeans ... I talked to Neil Slaven quite extensively years ago and he

was telling me how the blues to him was different, almost like a fantasy

world you know, of blues people that were like cartoon people, like

there was a comic strip of Robert Johnson, you know what I mean. He

said itís hard to visualise that all these people you grew up with are

real people and they had lives. Music was just part of their life. You

think, somebody like Robert Johnson, itís just all music but he had

relatives and he hung out with his friends. When I was a kid, about 14,

I went to

Omar: Yeh, see I

want to make those tribute records because I love those guys. I've made

22 records, I've written enough songs to fill a book up; do you really

want to just make another CD with 12 more songs I wrote. I mean, I like

writing my songs and I write some good stuff but if I want to do

tributes because itís good fun.... All of my friends who play love Bo

Diddley and they love Howlin Wolf so when I say, ďLetís get together and

do some Howlin' WolfĒ they are like, ďIím on itĒ because itís fun with

great songs. Iíll never quit writing. Iíve got some 50 songs that I

wrote that are waiting to be recorded and Iíll record some of them

eventually but my mind set is not just to make another record with

another 12 of my songs. I'm gonna try to do these tributes if I can;

gonna get in touch with my friends to see if they're interested; I don't

want it to just be my thing.

Omar: Yeh, see I

want to make those tribute records because I love those guys. I've made

22 records, I've written enough songs to fill a book up; do you really

want to just make another CD with 12 more songs I wrote. I mean, I like

writing my songs and I write some good stuff but if I want to do

tributes because itís good fun.... All of my friends who play love Bo

Diddley and they love Howlin Wolf so when I say, ďLetís get together and

do some Howlin' WolfĒ they are like, ďIím on itĒ because itís fun with

great songs. Iíll never quit writing. Iíve got some 50 songs that I

wrote that are waiting to be recorded and Iíll record some of them

eventually but my mind set is not just to make another record with

another 12 of my songs. I'm gonna try to do these tributes if I can;

gonna get in touch with my friends to see if they're interested; I don't

want it to just be my thing.