"The

final stanza is like a dream. Big Joe Williams looks down at Martin

Luther King’s face, and vows to the slain civil rights leader that

we’ll keep marching on - even unto Resurrection Day".

While

the fires were still burning up and down the block in the Chicago

riots that erupted just after Martin Luther King’s assassination,

Otis Spann gave a concert at a storefront church where he performed

two hauntingly beautiful blues compositions: “Blues for Martin

Luther King” and “Hotel Lorraine.”

Although

the guitar has always been the most heralded instrument in the

blues, there have been many great blues pianists, including Little

Brother Montgomery, Pete Johnson, Big Maceo Merriweather, Roosevelt

Sykes, Champion Jack Dupree, Charles Brown, Memphis Slim, Katie

Webster, James Booker, Professor Longhair and Sunnyland Slim.

My

choice for greatest blues pianist of all time is Otis Spann, the

brilliant singer and gifted pianist in Muddy Waters greatest band.

He also was the house pianist for Chess Records, playing on

recordings by everyone from Little Walter to Bo Diddley. Spann was

so skilled and multi-talented that he became one of the most

in-demand session pianists of all, playing with Johnny Shines, Floyd

Jones, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy and James Cotton.

Spann

was born in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1930 and only reached the age

of 40, dying in 1970. In that short period, he left behind a legacy

of beautiful blues masterworks that have never been surpassed.

Although Spann made his reputation as a brilliant and inventive

pianist, I also love his smoky, soulful vocals, on full display on

the beautiful records he made as a solo artist, including “Otis

Spann Is the Blues,” “The Blues Never Die” and “Walking the Blues.”

He was

like a brother to Muddy Waters and the incredible musical rapport

between the two men anchored one of the greatest electric blues

bands of all time.

Otis

Spann performed on one of the best live blues concert records,

“Muddy Waters at Newport,” recorded at the Newport Jazz Festival in

July of 1960. Because of a riot in the town of Newport, the last two

days of the concert were cancelled, and Spann, with the acclaimed

poet Langston Hughes as his co-author, composed and performed a

spontaneous “Goodbye Newport Blues,” a sweet and sad elegy to the

Newport festival.

Looking

back on it now, his song seems to have foreshadowed another

spontaneous elegy that Spann would compose eight years later, in

1968.

Almost

immediately after Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4,

1968, Otis Spann and Muddy Waters played a tribute at a storefront

church on 43rd Street in Chicago. Spann’s breathtaking tribute for

King can be found on “Rare Chicago Blues, 1962-1968,” issued by

Rounder Records.

Producer

Pete Welding described the dangerous and even life-threatening

context of Spann’s performance in the liner notes. “Buildings were

burning up and down the street as the Chicago ghetto riots began.

Accompanied in a funereal style by drummer S. P. Leary, Otis’ strong

shouting voice and elegant piano are beautifully showcased in two

pieces inspired by the assassination.

“Spann’s

lyrics, certainly improvised, are an extraordinary testimonial of

his feelings and evoke the pain and intensity of that day. Muddy

Waters can be heard echoing Spann’s feelings in the background as he

urges him on.”

“Hotel

Lorraine” begins with Spann’s melancholy and exquisite piano and

then his slow, sorrowful voice begins to tell the story of King’s

death at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis earlier that day. This song

is truly a “first draft of history” and it is so memorable that it

is hard to imagine how it could have been composed so quickly.

Spann

describes Dr. King talking to his friends in front of the Lorraine

Motel, and how “the poor man didn’t feel the pain” of the sudden and

unexpected gunshot. “People ask why violence has taken over and the

devil got into that evil man,” Spann sings, and then plays a lovely

piano break that seems to pour out all the anguish and beauty of

King’s life.

Then

Spann’s quiet, mournful voice suddenly roars out the last verse of

“Hotel Lorraine” with gospel intensity:

“Dr.

King was a man that could really understand.

You know

his last words he said:

‘God

knows I’m going to the Promised Land.’”

Spann

shouts out the words “God knows” as an outcry of triumph and

exaltation mingled with deep pain and grief.

|

Otis Spann’s Blues

for Martin Luther King

His second song at the storefront church in Chicago that day

is even more powerful. So many of Spann’s best solo

recordings are beautiful and full of feeling, but “Blues for

Martin Luther King” may be my favorite of all his

recordings.

It begins the only way it could on that day of heartbreak

and loss, with Spann asking those gathered in the storefront

church if they heard the news about what happened “down in

Memphis, Tennessee, yesterday.” With a raw, gospel-fueled

urgency in his voice, Spann sings, “There came a sniper,

Lord, that wiped Dr. Luther King’s life away.”

During a magnificent instrumental break, Spann shows how a

piano can wail and cry out wordlessly. It is a marvellous

tribute to the man whose life had brought so much hope to

the black community and whose death can never be forgotten.

The final verse reminds us that the assassination was not

just a political crisis or a stumbling block for the civil

rights movement. The movement had lost a leader, and the

nation had lost a martyr. But Martin Luther King’s family

lost their husband and father. |

|

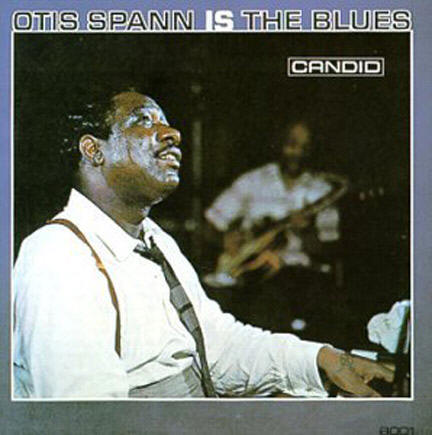

“Otis Spann Is the

Blues” is a beautiful recording on Candid. Spann recorded

two deeply moving tributes to Martin Luther King the day

after his murder.

|

Almost

no one else even thought to reflect upon the family’s great loss,

yet the deepest and most permanent wounds were inflicted on King’s

wife and children. Otis Spann had the sensitivity to write about

this most personal dimension of grief and anguish. His final verse

captures, for all time, their great loss.

“Oh,

when his wife and kids came down, people,

all they

could do was moan.

Oh, you

know when his wife and kids came down,

all they

could do was moan.

Now the

world’s in a revolt because Martin Luther King is gone.”

The Big Heart of Big Joe Williams

The face

of Big Joe Williams, with its deep scars and roughly etched lines,

was like a roadmap of his soul - or a map of the endless highways,

back alleys, and train tracks he traveled as a wandering bluesman

for close to six decades.

In his

countless songs and albums, he left behind a travel journal in

musical form of those endless roadways and byways - decades and

decades worth of the Delta blues that Big Joe had recorded in

defiance of all passing musical styles and fads.

Big Joe

Williams played the genuine Delta blues first, last and always, from

the first song he played at some Mississippi levee camp to the last

concert hall on his life’s journey.

Born in

Crawford, Mississippi, Big Joe Williams hoboed all over the South -

and then traveled onward all over the rest of the country - for more

than 50 years, playing his deep and vital brand of Mississippi blues

on his self-invented, nine-string guitar, hitch-hiking, hopping

trains, playing in juke joints and levee camps, touring with

minstrel shows, spending time in jail, and always rambling on to the

next town.

In his

story “Me and Big Joe,” Michael Bloomfield, the great blues musician

who played spellbinding lead guitar with the Paul Butterfield Blues

Band and with Bob Dylan on “Highway 61 Revisited,” wrote that being

with Big Joe Williams was “being with a history of the blues - you

could see him as a man, and you could see him as a legend.”

Bloomfield said that Big Joe “had America memorized” because he had

traveled tirelessly all over the nation, singing the blues in

Mississippi juke joints in the 1930s and 1940s, New York

coffeehouses in the 1950s and 1960s, and university blues festivals

in the 1970s.

Bloomfield wrote, “From forty years of hiking roads and riding rails

he was wise to every highway and byway and roadbed in the country,

and wise to every city and county and township that they led to. Joe

was part of a rare and vanished breed - he was a wanderer and a hobo

and a blues singer, and he was an awesome man.”

This

big, powerfully built man had lived a rough-and-tumble life, and

blues critic Barry Pearson wrote, “Big Joe Williams may have been

the most cantankerous human being who ever walked the earth with

guitar in hand.”

But

Pearson quickly added that, “he was an incredible blues musician: a

gifted songwriter, a powerhouse vocalist, and an exceptionally

idiosyncratic guitarist.”

That is exactly why it is

so touching that this road-toughened, cantankerous and combative man

was moved to compose such a tender and deeply affecting remembrance

of Martin Luther King right after his assassination in Memphis.

|

Big Joe Williams laid his soul bare on “The Death of Dr.

Martin Luther King.” He sounds shaken to his core by King’s

death, and his powerful voice erupts with a complex mixture

of sadness, tender concern, inconsolable grief, bitter anger

and sheer outrage.

Big Joe plays a beautiful accompaniment on his

strange-looking, nine-string guitar and Charlie Musselwhite,

a master of the blues harp, plays a lovely, mournful elegy

on his harmonica. “The Death of Dr. Martin Luther King” can

be found on “Shake Your Boogie” on Arhoolie Records.

Williams begins by asking his listeners if they had heard

the unbearable news.

“Did you get the news, people, |

|

Big Joe Williams

plays the unique nine-string guitar that he invented to give

his blues a distinctive sound. Big Joe wrote a profoundly

moving tribute to Martin Luther King.

|

what

happened in Memphis, Tennessee, yesterday?

Come

along some mean old sniper and carried Dr. Martin Luther King away.”

Big

Joe’s next verse says it all. He traces the recent trajectory of

King’s involvement in the civil rights movement, recalling the

Bloody Sunday march in Selma, Alabama, the Mississippi freedom

summer, and King’s last stand for freedom — his solidarity with the

striking sanitation workers of Memphis.

“Well,

Dr. Martin Luther King marched in Selma,

He

marched in Mississippi too.

But when

he got to Memphis, Tennessee, man, it wouldn’t do!

Dr.

Martin Luther King is dead.”

The next

verse leaves me with ashes in my mouth and a sadness that has no

answer on earth.

“Well,

he died last night boys,

Oh Lord,

with a bullet in his head.”

March on Resurrection Day

The

final stanza goes by like a dream, or a supernatural visitation. Big

Joe Williams sings that he goes to the graveyard, looks down at

Martin Luther King’s face, and vows to the slain civil rights leader

that we’ll keep marching on - even unto Resurrection Day.

“I went

to the graveyard,

I peeked

down in Dr. Luther King’s face.

I said,

‘Sleep on Dr. Martin Luther King.

We’ll

march on Resurrection Day.’”

Those

verses are brilliant and overwhelming and they are shot through with

beauty and faith. They absolutely floor me. Like Big Maybelle, Big

Joe Williams has refused to let death have the last word.

Resurrection has the last word.

Those

lyrics are not sung as if Big Joe is barely holding onto some

forlorn hope.

Rather,

they are sung with all the passion and vigor of a man who has

marched all over the land and has been tough enough to outlast all

the hobo camps, the forced labor of the levee camps and the brutal

railroad guards. Big Joe was powerful enough to endure all the

rainstorms and Mississippi floods, outlive all the segregation

decrees and Jim Crow laws, and thrive despite all the hunger and

hardships of a life lived constantly on the move.

Big Joe

Williams always marched on. He may have been drunk or hung-over or

sick or penniless, but he kept moving.

So did

Martin Luther King. He always marched on to the next struggle. He

marched on from the Montgomery bus boycott to the Birmingham jail to

the Mississippi March Against Fear to the Selma march for voter

rights to the fight against slum housing in Chicago to the

sanitation strike in Memphis.

At the

end of all this marching, Martin Luther King began marching with

great vision and courage towards Resurrection City and his showdown

with the federal government in Washington, D.C.

The Mule

Train from Marks, Mississippi, made it to the nation’s capital.

Martin Luther King did not.

Yet there is that final, beautiful promise from Big Joe Williams to

Dr. King: “We’ll march on Resurrection Day.’”

‘Threatened with Resurrection’

I am

haunted by that verse: “We’ll march on Resurrection Day.” In

the aftermath of King’s murder in Memphis, many activists still kept

the faith and marched on in the belief that death would not have the

final word for the Freedom Movement. And what destination did they

reach? What is the name that they gave to the shantytown of shacks

and tents that they built near the Lincoln Memorial? Resurrection

City.

They

marched all the way to Resurrection City in Washington, D.C. And

there, in that shantytown of poor people, they heard Muddy Waters

and Otis Spann keeping the faith with the spirit of Martin Luther

King and playing the blues on the streets of Resurrection City.

That is

only the first level of meaning in Big Joe’s song. The deeper level

is that death shall not have the last word, because after death

there is the promise of resurrection. On Resurrection Day, we will

march again for justice. We will arise and walk down the Freedom

Road.

The

Catholic priest and dissident peace activist, Fr. Daniel Berrigan,

wrote that, despite all earthly evidence to the contrary, the

state-sanctioned violence and death used to suppress rebellions will

not have the final say in our world. Rather, as Berrigan wrote, one

day Sheriff Death himself will be hauled away. That day is the

Resurrection Day that Big Joe Williams described.

The poet

John Donne wrote: “Death be not proud.” That is the profoundly

hope-filled and life-giving title of one of his finest sonnets. Here

are the final lines of John Donne’s “Death be not proud.”

“One

short sleep past,

we wake

eternally,

And

death shall be no more;

Death,

thou shalt die.”

A

Guatemalan poet, Julia Esquivel, once wrote that the tyrannical

regimes that oppress and crucify the poor are “threatened with

Resurrection.”

The

powers that be were, in fact, threatened when the U.S. civil rights

activists of the Freedom Movement cast off their fear of arrests and

brutal police and jail cells and death itself, and kept on marching

for justice. Dr. King and others had realized that death would not

have the last word.

The

names of the martyrs inscribed in black granite on the Civil Rights

Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, remind us that the price of freedom

can be very high. Big Joe Williams reminds us that we’ll march onto

Resurrection Day.

|

The Fighter —

Champion Jack Dupree

Champion Jack

Dupree is a fascinating figure in the blues. He earned his

sobriquet, “Champion Jack,” as a fighter who boxed in more

than one hundred boxing matches. He won Golden Gloves and

state championships before pursuing his career as a blues

pianist and singer.

But those

fights were only part of a lifetime struggle that began

after he was orphaned at the age of two when both his

parents died in a fire. He was sent to the same orphanage in

New Orleans where Louis Armstrong was raised.

After his

boxing career ended, Dupree moved to Chicago and began

playing blues piano for a couple years before serving in the

U.S. Navy during World War II - another fight on another

battlefield. That fight was followed by yet another when he

was held as a Japanese prisoner of war for two years.

Even though

Dupree had fought in World War II, he asked the U.S.

government to stop fighting in Southeast Asia in his song,

“Vietnam Blues.” His long experience of poverty and racism

in the United States made him sympathize with the suffering

of poor people in Vietnam. |

|

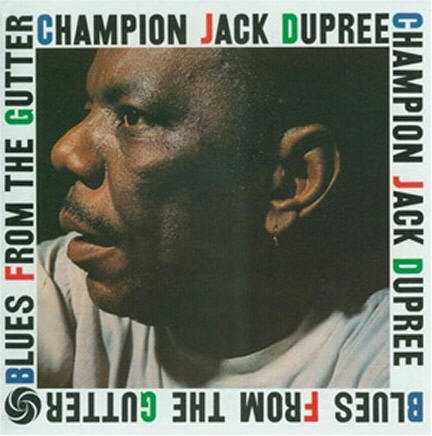

One of the finest

sets ever recorded by Champion Jack Dupree was “Blues from

the Gutter,” on the Atlantic Jazz label.

|

“Why don’t they

leave Vietnam, leave those poor people alone.

They got a hell of

a problem, just like I have at home.”

In one of the finest

moments in his fighting career, Dupree spoke out for the lives of

the people targeted by his country’s bombs. He also expressed

sympathy for the mothers of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam, when he asked

the U.S. military to withdraw its troops.

“Well, I know

every mother be glad to see her sons come home.

Yes, Uncle Sam

just as well pack up, pull out and go back home.”

Champion Jack Dupree’s

finest album, “Blues from the Gutter,” is a riveting glimpse into

the dead-end world of disease, drug addiction and death. It is truly

blues for the down-and-out.

Dupree looks with

unswerving honesty at what Hank Williams used to call “pictures from

the other side of this life” — the side most of us prefer not to

see.

Even though his songs

take on subjects so full of suffering and sickness, Dupree’s vocals

and piano playing are beautiful, and his lyrics show us how the

blues can reveal the most distressing aspects of the human

condition, yet still be overflowing with life, vitality, humor and

insight.

In “T.B. Blues,”

Dupree becomes the voice of a man with tuberculosis, at that time a

deadly and incurable disease. He manages to make a beautiful work of

art out of a fatal diagnosis.

“Well I got the

T.B., and the T.B. is all in my bones.

Well, the doctor

told me that I ain’t gonna be here long.”

Some things are almost

worse than dying, such as being abandoned in your hour of greatest

need by the very people you thought were your closest friends.

This song is light

years away from the kind of pop music conventions that pledge, in

Carole King’s words, “You’ve got a friend.” Instead, Dupree sings a

hard-won truth about the faithlessness of friends, warning that many

will even stop coming to visit at all if they are even asked for

help.

“Well, the T.B. is

all right to have,

But your friends

treat you so lowdown.

Yeah, don’t ask

them for no favor,

They will even

stop coming ‘round.”

Unlike many forms of

rock and pop music aimed at youthful audiences, the blues most often

was created by and for adults. It is unafraid to take on everything

under the sun that grown-ups enjoy, suffer, fear or dream about.

The great blues

artists sing of love and sex, marriages and break-ups, drinking and

hangovers, good times and terrible blows, faith and doubt, war and

peace, injustice and racism, and as Champion Jack Dupree showed us,

our lifelong boxing matches with disease and death.

Yet, even when the

great range of lyrical themes in the blues is understood, it is

still a mystery how Dupree found beauty and meaning in his blues

from the gutter.

Singing the Expatriate Blues

Champion

Jack Dupree became one of the first blues expatriates. He left

America for Europe in 1959 and stayed there the rest of his life

until his death in 1992.

Several

blues artists who wrote with strong convictions about social and

economic justice were the very ones who packed their bags, left the

United States, and moved to Europe. For many, the move was

permanent, and although they may have returned occasionally to give

concerts or record their music, they never returned to live in the

land of their birth.

In his

book, The Legacy of the Blues, Samuel Charters devoted a

chapter to Champion Jack Dupree and explained his choice to leave

America for good. Many American blues musicians found greater

respect and love for their music in Europe, and better working

opportunities. But the most important issue for these expatriate

bluesmen was their desire, in Charter’s words, “to escape America’s

racism.”

Charters

wrote, “Eddie Boyd is only one of the blues artists who has settled

down in Europe. Memphis Slim and Willie Mabon live in Paris, and

Champion Jack Dupree has his house and family in England. Why have

they left the United States? The most important reason always is the

lack of severe racial hostility in countries like France or Denmark

or Sweden.”

It is a

sad commentary on America’s history of racial discrimination and

hatred that many of the blues musicians who cared so deeply about

social justice and expressed their conscience and humanity so

eloquently in their music, felt driven to leave their homes and

become expatriates for the rest of their lives.

Way Up on the Mountaintop

In his

song, “The Death of Luther King,” written in 1968 less than a month

after Rev. King was murdered, Champion Jack Dupree played a slow and

mournful melody on the piano for an audience in Paris. The tinkling,

cascading notes of his piano accompanied his opening words, a

talking blues about the loss of Dr. King.

In his

spoken introduction, Dupree said in a very slow, solemn voice, “Well

the world lost a good man when we lost Dr. Martin Luther King, a man

who tried to do everything. He tried to keep the world in peace. Now

the poor man has gone to rest. So go on Dr. Martin Luther King and

take your rest. There will always be another Luther King.”

I’ve

always loved Dupree’s singing. His rich voice feels warm and

familiar and comfortable, even when his deeply felt vocals may be in

service of story-songs that are grim or despairing or down in the

gutter - or, in the case of this song, when his subject is a tragedy

beyond the telling.

So when

his spoken introduction is over, Dupree begins singing in that warm,

comforting voice, sounding for all the world like a wise old uncle

giving some friendly advice. But his calm, soothing voice makes his

words seem all the more startling and disturbing by contrast. He

gives no quarter in this song. He is a man who has come to tell the

truth.

“It was

early one evening when the sun was sinking down.

Early in

the evening some dirty sniper shot Martin Luther King down.

He was

nothing but a coward. He dropped his gun and run.

But he

will never have no peace. He’ll always be on the run.”

He

performed “The Death of Luther King” for an audience in Paris in

late April of 1968, three weeks after King’s assassination. Champion

Jack Dupree sang out the words that Martin Luther King had spoken in

a Memphis church on the day before his death.

“The

words that he said just before he died:

‘I’m

going up on, I’m going way up on,

Way up

on the mountain top.’”

Then

Dupree spoke softly to his listeners once again, quietly playing the

piano while he utters the next few sentences in a subdued,

introspective manner. It’s as if he were only speaking to himself,

maybe daydreaming or thinking out loud, trying his best to

understand this incomprehensible tragedy.

This

quietly thoughtful passage is very unsettling. Dupree creates a very

intimate atmosphere, as if we, his listeners, were sharing his most

private thoughts. And what private thoughts we overhear!

He

meditates on the series of political assassinations in America, and

the effect of his reverie becomes even more private and personal in

the final verse when Dupree decides that if the reactionary forces

in America have not hesitated to shoot down Lincoln, Kennedy and

King, Dupree himself doesn’t stand a chance.

Dupree

says quietly to himself, “Yeah, they shot him down, just like they

done all the rest of them. They shot down Abraham Lincoln, they shot

down President Kennedy, and they took poor Martin Luther King. So

you know I don’t stand a chance. I ain’t nobody.”

At the

moment when he says, “I ain’t nobody,” the song enters into another

dimension.

He

begins singing directly to his white audience in Paris, forthrightly

voicing what is really on his mind. It’s as if his thought that “I

ain’t nobody,” leads him to confront the elephant in the room that

everyone has been politely ignoring: the element of race and

discrimination, and how that makes some people in society feel that

everything is just fine, and makes others feel that, “I ain’t

nobody.”

The

strange thing is that Dupree is talking about this confrontational

truth in a voice just as warm and gently comforting as it can be.

It’s a moment of real artistry.

He

speaks a truth almost too terrible for words, yet he states it with

such warmth and humanity, that instead of feeling accused, I would

guess that his audience in Paris that day felt disarmed by his

gentle tone, as if he had invited them to really understand Dupree’s

own hard experiences in a very personal way, so they might begin to

understand - perhaps for the first time - how racism really feels

from the inside.

He has

invited them to understand, for just a moment, his own feelings

about freedom, and the denial of freedom.

Again,

this song seems to me an artistic triumph. For the humanity of his

voice is so welcoming that his listeners that day may have felt

disarmed enough to open their minds up to the feelings of all those

in our society who have never felt free.

Dupree

sings these very personal lyrics directly to his audience, and his

gently voiced words land with shattering impact.

“I know

you people, I know you’re glad you ain’t none of me.

I know

you people are glad, I know you’re glad you’re white and free.

Oh what

will, what will become of me?

Oh, I am

begging, yes, I’m begging to be free.”

Champion

Jack Dupree delivered that highly personal appeal three weeks after

Martin Luther King was shot to death. He was living by choice in

Europe, an entire ocean away from the segregation and church

bombings and discrimination and assassinations in his country of

birth.

So, in

begging to be free, he was making an appeal on behalf of his people

still suffering discrimination back in America, the people who had

placed so much hope in the Freedom Movement, only to see so many of

its leaders killed.

|

Today, when I listen to his song, “Death of Luther King,” I

remember how I felt when I looked numbly at the water

flowing over the names of dozens of martyrs inscribed in

black granite at the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery,

Alabama.

It felt like the end of hope to stare at the names of Medgar

Evers, Rev. James Reeb, Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo,

Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, Denise

McNair, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and

Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Too many martyrs and too many dead,” sang Phil Ochs, one of

the most powerful political folksingers of his generation.

In “Here’s to the State of Mississippi,” Ochs sang an even

more uncompromising truth about the murders of so many

martyrs:

“Here’s to the state of Mississippi,

For underneath her borders, the devil draws no lines.

If you drag her muddy river, nameless bodies you will find.

Oh, the fat trees of the forest have hid a thousand crimes, |

|

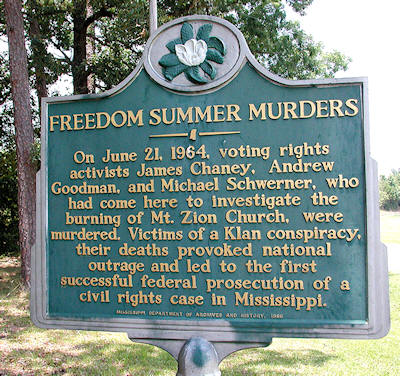

“Freedom Summer Murders.”

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were shot

to death by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi while

working for voting rights during the Freedom Summer of 1964.

|

The

calendar is lying when it reads the present time.”

Yet the

death of hope can also bring the dawn of its rebirth. Every time one

a civil rights worker was martyred, others arose in his or her

place, and countless more were radicalized to take up the struggle.

When Champion Jack Dupree

sings, “Oh, I am begging, yes, I’m begging to be free,” I can hear

the echo of Martin Luther King’s soaring and majestic words, “Free

at last, free at last, Thank God almighty, we are free at last.”