Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Slave To The Blues |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Transcribed from the original typed

document, this article includes 'footnote' comments which may be found by

hovering over the images of the slave shackle, shown here:

This article is part of a far larger work ('Slave To The Blues') which seeks to focus on the secular roots of the Blues back in slavery times in the USA. In collaboration with my younger brother, Rex, and blues brothers, Alan White, Robin Andrews and Dai Thomas we intend to highlight the non-religious music of the African American before 1865; and at the end of the Civil War. Paying particular attention to the ‘corn shucking’ songs.

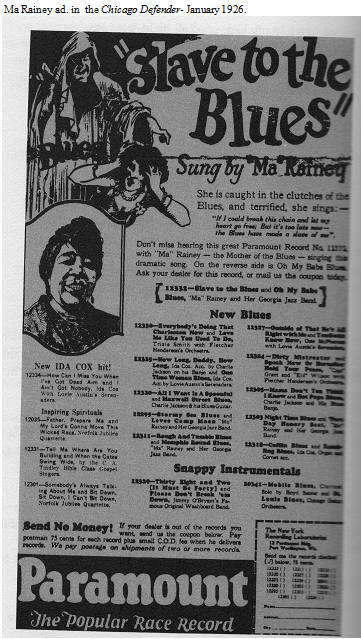

The scars of slavery, both physical and mental, ran deep and so it is not surprising that some 60 years after the end of the Civil War, they would still be felt running through the Blues. In 1925 one of the finest of the early vaudeville-blues singers, Ma Rainey, could record her Slave To The Blues [Paramount 12332] knowing it would still strike a strong emotional chord in her audiences - which could have included ex-slaves by then in their 80s and 90s.

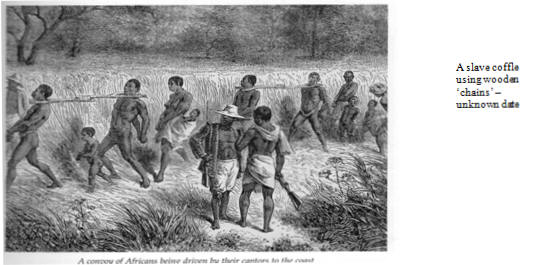

Writing in 1981, Sandra Lieb, rightly points up (especially in verses 1 and 2) that “The woman’s passivity is…emphasized by songs which describe her as a slave or a victim.” (3) But as well as the “emotional bondage” of such songs Lieb is quick to identify that “…the slave image has a cruel historical antecedent; hopelessly trite in a white song, it evokes the most painful, bitter responses and memories of literal chains”. (4) The chain was only second to the whip among the cruel icons of the peculiar institution of slavery. Indeed, for taking coffles of blacks across country, it was essential. The “negroes [sic] en route were usually in manacles and bound together in coffles,”. (5) In 1992, Marion B. Lucas included a contemporary account by “James H. Dickey, a white minister, [who] left a poignant description of a bizarre caravan of slaves he met trudging down the road between Paris and Lexington [ in Kentucky] in 1822…To his shock, a slave coffle appeared. Two violin-playing bondsmen led the way, followed by two slaves with cockades decorating their hats. In the midst of the caravan of about forty male bondsmen, a pair of chained hands waved the American flag. The slaves, securely handcuffed, were joined together by short chains which connected to a forty-foot long chain that ran between them. About thirty women, tied together at one hand, followed the caravan. All marched in “solemn sadness”, the minister wrote.” (6) Sadly, Dickey did not refer to the sounds emanating from the two fiddlers at the head of this coffle who would presumably not have been playing ‘jolly’ music - unless forced to by the slave traders - but tunes of lowdown gut-busting misery. But fortunately, an almost unique recording by guitarists Peg Leg Howell and Henry Williams and fiddler Eddie Anthony surely convey something of what the two enslaved fiddlers, at least might have WANTED to play; even if it was not recognized yet as Blues in 1822. With a deep resonance of their combined humming or ‘moaning’ shot through with some of the most intensely emotional fiddling on a record, Moanin’ And Groanin’ The Blues [Columbia 14270-D] may well be what I call an ‘oral camera’ on this horrific scene in the early 19th. Century. Howell only includes a couple of verses on the record:

A ‘fairy’

appears to be a (Georgia?) corruption of ‘faro’

which in Mississippi slang of the 1920s blues “just

means a woman” .(8)

According to Calt and Wardlow ‘faro’

In a contrasting atmosphere to Rev. Dickey’s report, some 20 years later in Springfield, Missouri; is one by future US President Abraham Lincoln. Along with his friend Joshua F. Speed they were on their way to the latter’s home in Kentucky on 27th. September, 1841. At Springfield, Lincoln states: “We got on board the Steam Boat Lebanon, in the locks of the Canal about 12. o’clock. M [morning?] of the day we left, and reached St. Louis the next Monday at 8 P.M.” (11) After some time steaming down the Mississippi River without much interest (at least to Lincoln), he was suddenly confronted at St. Louis by a coffle of slaves. “A gentleman had purchased twelve negroes [sic] in different parts of Kentucky and was taking them to a farm in the South. They were chained six and six together. A small iron clevis was around the left wrist of each, and this fastened to the main chain by a shorter one at a convenient distance from, the others; so that the negroes [sic] were strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line. In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparently happy creatures on board. One, whose offense for which he had been sold was an over-fondness for his wife, played the fiddle almost continually; and they danced, sung, cracked jokes, and played various games with cards from day to day..” (12) I wonder if it ever occurred to Lincoln that all this ‘happiness’ was the unfortunate slaves only psychological weapon to stop them going crazy with grief and anger at being torn so cruelly from all their loved ones and friends. This weapon also had another edge; that of not showing any distress in front of the whites who themselves would be absolutely distraught in the same situation - the blacks thereby claiming moral superiority over their so-called ‘masters’. In 1963 another US writer, for the Life Magazine World Library, stated an unequivocal fact regarding the transatlantic slave trade. “It was a crime of Europeans and Arabs and Africans and, in the truest sense, it was a crime of mankind.” (13) not to forget the Americans! But it was the Arabs who were among the first to make that trade a more viable proposition. Coffles of slaves have trudged across the Sahara for centuries. Thomas notes that “one can explore how far the medieval trans-Saharan trade in black Africans, from the coast of Guinea, was managed by Arab mullah -merchants in the first centuries after the Moslem penetration of Africa, long before Prince Henry the Navigator’s ships were seen in West Africa.” (14) Prince Henry, “brother of the King of Portugal,” was responsible for the first shipload of African slaves to Europe “on 8 August 1444,” (15) But with “the introduction of the camel (native to Asia) in AD 300, much bigger cargoes could be carried with greater ease and efficiency than had been possible with the gangs of human bearers, and the trans-Sahara traffic greatly increased. Eventually it grew huge, with camel trains sometimes numbering many thousands of animals accompanied by attendants, guards and merchants.” (16) The guards were not there only to defend these trains against robbers along the way, but also to ensure that the “human bearers”, who were usually enslaved Africans, did not try to escape or ‘mutiny’. Of course these larger camel trains did not make the slave coffles redundant. The Arabs were not about to relinquish such a profitable trade. “Such tribes as could not be enslaved successfully, as the Manyema of the upper Congo, were adopted as allies by Arab traders, and became themselves slave traders and raiders of the most inveterate and relentless character. The Hausas and Fulahs of the Egyptian Sudan were extensive owners of and dealers in negro [sic] slaves, and they would resent as quickly as a white man an attempt to identify them with negroes. [sic] But the Arab dealer was no respector of persons, and when opportunity offered he did not hesitate to sell to the white slaver his allies of a different stock, along with the negroes [sic] whom he had bought from them.”. (17) Indeed, the word ‘coffle’ comes from the Arabic ‘kafila’ referring to a caravan of camels, etc. and is defined as “…a line of animals, slaves, etc. fastened together.” (18)

This might explain the side recorded by

Rev. J.M. Milton: The Black Camel Of Death [Co 14501-D] at his one and

only session in 1929. This is the sole recorded example of the title in B&GR

Rev. J.M. Milton sometimes calls it “Black Camel’s Death” or “Black Camel Death” I am convinced that this goes back to the infamous coffles once traversing the US in the 19th. Century and their centuries-old form of transportation on the African continent. The untold numbers of men, women, and children, who literally fell by the wayside of the horrendously arduous transcontinental journeys and left for dead was surely transfixed in the psyche of surviving slaves.

The camel, it is not generally known,

appeared in the United States during the 19th. Century! I have only

come across two references to this little-known phenomenon. During the 1850s

the Sante Fe (Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry.), a railroad often featured in the

early blues, “was still in a fetal stage, in the

area of what today would be the states of Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona

and California, there were less than two people to the square mile. The trail

from Kansas to Santa Fe was an old one that had been used as a trade route when

Santa Fe became an American town in 1846. From Independence, Missouri, the

state border, the 850-mile trail was by the time of the Santa Fe railroad

project a well-defined route. The period was one when almost any new idea

[re transportation] was given a try. In

1855, for example, Congress amazingly enough had appropriated $30,000 for an

experiment to bring camels to the United States to be used for transport in the

southwest. By 1857 nearly a hundred camels had been imported to a Texas Gulf

port.

Marshall’s last sentence is inaccurate. Alvin Harlow tells us that in the beginnings of mail and express lines, another such experiment was introduced to import camels, into the US. In 1862 “Pack trains and express lines started in several directions, and… ‘an air of oriental magnificence was imparted to the scene by the advent of a long train of camels, loaded to an astonishing extent’”. (23) However, “the camel transportation service was not greatly successful. American drivers did not understand them, their feet, accustomed only to soft desert sand, suffered on our stony western trails, and it was not practicable to shoe the cleft hooves.” (24) Camels also “frightened the horses wherever they went, and were finally forbidden use of the roads.” (25) Many were just set loose to roam in the Texas Panhandle and other areas for years afterwards. “The last one seen alive was in Arizona between 1885 and 1890.” (26) The pic. (1875) shows a ‘camel express’ which included black animals.

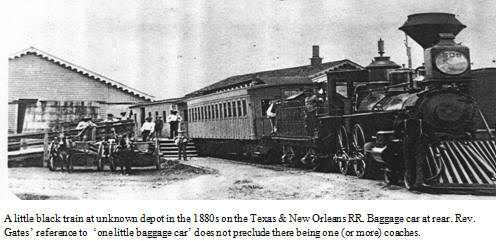

The ‘Judgement Bar’ being the station where the railroad forks, with the left track going to Hell and the right track going to Heaven. This scenario is made quite clear in another of Gates’ recordings around the same time. You Belong To That Funeral Train [OKeh 8398] is a variant of Death’s Black Train and one of 8 versions he made, all in 1926. But this train has no whistle or bell and when it leaves the final ‘depot’ (the Judgement Bar) it takes its passengers to heaven or hell.

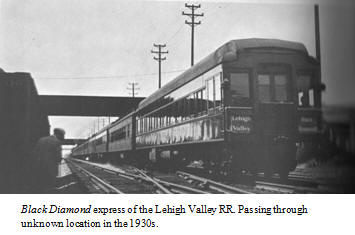

In 1930 the Rev. A.W. Nix gave the Hell train a name. Taken from a popular express on the Lehigh Valley Railroad he called it The Black Diamond Express To Hell. The L.V. RR. a major coal (aka black diamonds) carrier and also referring to his listeners skin colour, gives his sermon several layers of meanings. It was so popular a recording that six ‘parts’ were cut in the studios. On the final version, Nix calls the last depot ‘Farewell Station’ where The Black Diamond Express and its heavenly counterpart The White Flyer go their separate ways on the final journey. Sinners and saints say goodbye as the trains reach the point where the railroad track forks in the form of a switch or point; one going left and the other going right. Rev. A.W. Nix paints a terrifying picture for unrepentant sinners. Inspired no doubt by Rev. J.M. Gates’ equally terrifying Hell Bound Express Train [OKeh 8532] from 1927.

But if Rev. Milton could take his recording from a Charlie Chan book, where did Rev. J.M. Gates get his influences? Given that he had recorded all 14 sides about the black/funeral train in 1926; some three years before Biggers’ The Black Camel was published. Gates must surely have had knowledge of the ancient Arab saying re the black camel of death. Indeed, as a ‘clincher’ to the scenario I have posited, the one and only cover (also in 1926) of Gates’ Death’s Black Train contains a short spoken introduction which paraphrases this Egyptian saying! (see p.7) Rev. H.R Tomlin, who only made 8 sides, was a more formal preacher from an earlier time who opened his version with these words:

Nothing is known of Tomlin except he

had links with Atlanta, Georgia, home-base for Rev. J.M. Gates. Also the

Rigoletto Quartet of Morris Brown University, who accompanied this preacher on

his Death’s Black Train Is Coming

[OKeh 8375] were resident in Atlanta where the Morris

Brown University

In all the versions of the little

black/funeral train that have been discussed and/or I have listened to, none make reference

to a camel, or indeed to any other animal. In fact, excepting the Rev. J.M.

Milton recording and one other, throughout at least 5,000 pre-war gospel titles

listed in B&GR

This dearth of camel references is replicated in Judika Illes’ Encyclopedia Of Spirits, from which I have unashamedly drawn so freely. Containing details of ‘over a thousand spirits’ (according to a comment on the back cover) and their animals symbols/preferences/familiars, only six have connection with the ‘ship of the desert’ as the camel is sometimes called. Two of these spirits favour the llama – a species of, or at least is related to, the camel. Pachamama “is the living Earth…Creature: Llama.” (39) But unless made angry she is a benign deity. Supay “is the spirit of Bolivia’s mines and patron of miners…Animals: alpaca, llama (beasts of burden that carry what’s been removed from his mines)”. (40) Thirdly, there is Allat “Origin: Arabia…the feminine version of the name ‘Allah’. She is a pre-Islamic spirit who was once among the primacy deities venerated at Mecca.” (41) Along with Al Uzza and Menat, Allat formed “the trinity of goddesses mentioned in the Koran. They are the subject of the so-called ‘satanic verses’, …inspiration for Salman Rushdie’s controversial 1988 novel ‘The Satanic Verses’.” (42) As well as being “a spirit of abundance with dominion over human reproduction…She may have had dominion over trade routes, protecting those who traveled them.” (43) One wonders if this protection extended to the slaves that made up the Arabian coffles. Allat “appears in the guise of a beautiful, mature, fertile woman.” (44) and she is represented as an icon “On coins from the Roman province of Petraer [where] she appears as a robed woman holding a bundle of cinnamon sticks and standing beside a camel.” (45) Significant is the entry “Animal: Camel.” (46) The fourth spirit, by definition, includes the camel. Kwan Yin’s entry reveals all animals “are sacred…but especially horses.” (47) A point could be stretched for the inclusion of a fifth: Sacha Huarmi. Known variously as ‘forest/jungle woman’ “She lives in the Ecudorian Amazon rainforest near the base of the Andes. Sacha Huarmi is the Green Woman who protects and nurtures wild forest animals…Creature: All of them but especially anacondas.” (48) I t is implied that this spirit’s ‘creatures’ are animals of the jungle and forest. Even if once again, by definition, the camel could be included; the llama as an indigenous mammal of South America is generally found in the desert. None of these five spirits could be described as the ‘Black Camel of Death’! But the sixth one it transpires, could well-hit the target; plumb center! Linked with Lilith, ‘Queen Of Demons’, her name is Aisha Qandisha . If there was only one candidate to take the left-hand track out of ‘Farewell Station’ on the train to Hell, with links to the camel; then Aisha Qandisha (pronounced A-eesha Qand-eesha) would be that candidate. Listed as ‘The Holy Woman’ should not necessarily reassure the reader. “Beautiful Aisha Qandisha lingers near deserted Moroccan springs after dark. Men sometimes mistake her for a lady of easy virtue, but beware: that can be a fatal error. The clue that she is not an ordinary lady of the evening lies in her feet. Allegedly, even when appearing otherwise human, one foot or leg still resembles that of a camel, donkey, or goat. Aisha Qandisha is as adored as she is feared. She is a ‘great’ spirit venerated by Algeria’s Ouled Nail, a Berber tribe who are famed for their beautiful and independent dancers,” (49) The Berbers in North Africa would have been involved in the sub-Saharan slave trade and their countless coffles. Aisha Qandisha “causes death, illness and madness but also restores health and bestows wealth, abundance, fertility, and luck. She is a Lilith-like figure simultaneously dangerous and benevolent.” (50) Among other theories of origin she is thought to possibly have been “Kadash, the sacred harlot.” (51) Like Lilith she has a voracious sexual appetite and if a man does not please her when making love to her “she may then drown him.” (52) Definitely suited to the appellation ‘Black Camel Death’ on Rev. J.M. Milton’s recording. Illes adds that Aisha Qandisha is a “temperamental, volatile spirit, quick to scratch, strangle, or whip those who displease her or don’t obey her commands fast enough.” (53) Finally, as already stated there is the telling manifestation. Although this spirit is often depicted as a lovely woman there is “typically some little give away that she’s more than that, such as one goat, camel, or donkey foot. She wears long robes as camouflage; the animal leg may not be immediately apparent.” (54)

While back in 1938 an Estonian lady,

Leonora Peets, wrote a book called Women of Marrakesh. One ‘Margot

the Marrakesh Mystic’ put a chapter entitled The

Couscous of the Dead on the web. It features a particularly grisly practice

in this famous Moroccan city. Ms. Peets discovered that it was general

knowledge “some old women would stealthily disinter

corpses in the cemetery for mysterious reasons.”

(55) This led her to asking questions but “People

wee [sic] evasive about the reasons

Unlike Rev. J.M. Gates or the Taggarts, Rev. J.M. Milton’s Black Camel implies a reference to a little black train that has left Rev. AW. Nix’s Farewell Station, taken the left fork at the “damnation switch”, and is heading for the fiery terminus! A comparable fate, as seen through the eyes of enslaved blacks who ultimately died chained in a coffle; on the African and American continents over several hundred years and up to the end of the 19th. Century in the case of the US. As an interesting addendum to the Black Camel Death, the Bible (King James version) apparently, from a source on the internet, has 150 references to the camel in the Old Testament and 2 in the New Testament. These see the lowly camel in various roles as a beast of burden, a mode of transportation, for rearing as providers of milk, - and, at least among Arabs, as a source of food. But not as a harbinger of death, or Death itself. In the Book of Genesis alone there are a dozen references to the camel. [Genesis XXIV: 10,11,14,20,30,32,36,44,46,61,63,64.]. In an essential set of 6 CDs (for both the historian and the collector) called Goodbye, Babylon, famous Blues author David Evans cites verse 63 in relation to Rev. Milton’s The Black Camel of Death. (57) This runs:

But this has reference to his bride-to-be, Rebekah, who is coming to Isaac’s home with a dowry including a number of camels. This can be seen as a scenario in complete antithesis to death. It is far more likely that Rev. J.M. Milton took his inspiration from the ancient Arab saying via Rev. H.R. Tomlin, via Rev. J.M. Gates and the Charlie Chan mystery The Black Camel; rather than any biblical reference. This evolutionary chain ultimately has its origins in the awesome Aisha Qandisha, who in one of her most terrifying roles as The Black Camel of Death, probably gave birth to the old Egyptian saying in the first instance. To the British slave trader on the West Coast of Africa the black camel coffles would have been a very familiar sight. It was indeed they who were the main part of the ‘demand’ factor which inspired the ‘supply’ by the Arabs in the global economic equation. On the ‘slave coast’ of West Africa there were forts or castles manned by European nations such as Portugal and Spain. But the most prominent was the British establishment, the notorious Cape Coast Castle. All these locations had slave or ‘holding pens’ for Africans about to be sold to ships’ captains from the home countries (and elsewhere) to transport across the Atlantic Ocean. St. Clair wrote “many…came from Asante, marched, shackled, through the forest paths, and [got] their first sight of men with skin colour that was not black..” (58) The governors of Cape Castle knew that “many of the people whom they bought did not originate from Asante, but came from communities conquered by, and subject to, the Asante empire, or who had been brought to Asante as slaves from further inland..” (59) One, Governor Hippisley noted that a few of the slaves “were so pale in complexion as to be of North African or Middle Eastern appearance..” (60) Sinclair added: “Hippisley speculated, correctly, that the interior of Africa was not a desert, as some Europeans believed, but luxuriant and well populated, and that the slaves brought to the Castle may have come from the whole of the vast area of sub-Saharan Africa, east as well as west, and even beyond..” (61) Significantly, Sinclair notes: “It was only in the Asante invasion of 1807, during which men literate in Arabic who had seen the Mediterranean were found among the Asante army, that the British in the Castle began to understand..” (62)

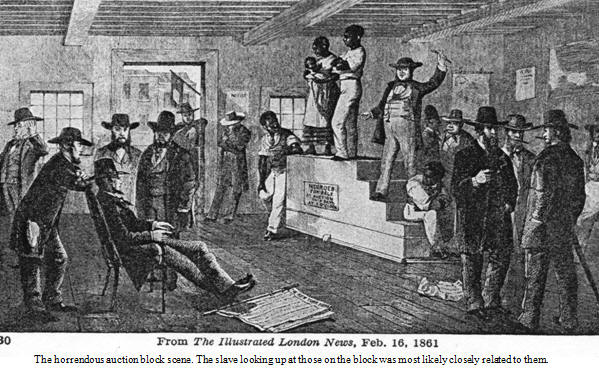

As has been seen the Arabic legacy of

the slave coffle soon reappeared in the American colonies and later, US states.

An ex-slave, Willis Winn, interviewed in 1937, told of “The

onliest statement I can make about my age is my old master Rob Winn, always

told me if anyone asked me how old I is to say I’se

borned on March 10, in 1822. I’se knowed my birthday

since I’se a shirttail boy, but can’t

figure in my head.”

(63)

This would make Willis Winn 115 at the interview. He goes on

to relate that when growing up (c. 1840s?) “They

was sellin’ slaves all the time, puttin’ ‘em

on the block and sellin’ ‘em, accordin’

to how much work they could do in a day and how strong they was. I’se

seed lots of ‘em in chains like cows and mules.

But the slave coffle had been around for some considerable time when Winn made these observations. Possibly going back to the 17th. Century. Certainly, as far as US writer, Walter Johnson, was concerned: “By the end of the eighteenth century slave coffles were a common sight on the roads connecting the declining Chesapeake – its soil exhausted by a century of tobacco planting – to the expanding regions of post-Revolutionary slavery, the Carolinas to the south and Kentucky and Tennessee to the west.” (66)

In the late 1700s there were no

railroads and only a few canals. Mostly, the only method of access across the

country was by river or dirt roads and ‘Indian’

trails.

By the 1820s, the then new states of Alabama and Mississippi had joined this evil trade. This throws another light on the crossroad (aka crossing) saga, in the Blues and in the early 20th. Century black communities. The ‘roadhouses’ referred to by Walter Johnson were early stop-over/trading points situated at the crossing – a more appropriate description on most occasions, in the 18th. C. and even as late as the 1910s and ‘20s. At a point where two dirt tracks crossed provided the coffles with a location where a sale of the human ‘freight’ could be set up via the auction block, as referred to by ex-slave Willis Winn above.. As a black woman from Sumter in South Carolina informed Hyatt in the early 1930s, this icon of the Blues graduated into roads and later even railroads. “ Jes lak if a railroad crossin’ have a road cross it, an’ cows goin’ cross it, well, dat’s a fork [crossroad], yo’ see..” (68)The unidentified woman goes on to explain an elaborate mojo to split up a relationship in the eternal triangle scenario which involved the crossroad/crossing.

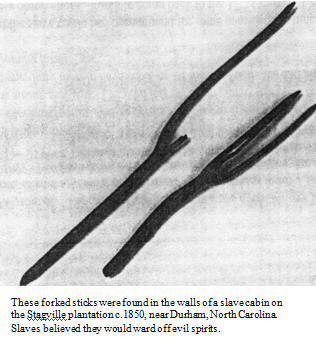

In West Africa, a Hausa belief runs “If one dreams of a man who is sitting alone while passers-by do not seem to notice him, that man is going to die soon.” (71) The Hausa were one of the major peoples (rather than a single tribe) enslaved in what was to become later, Southern USA. The Hausa language was second only to that of Swahili in the numbers of people who used it and its widespread distribution throughout the African continent. “In the days of slavery both the men and the women were much sought after because of their superior qualities and were highly valued in North Africa than slaves taken from any other Sudanese people.” (72) Many West African beliefs traveled via Haiti and vodou/voodoo to the Deep South and becoming ‘hoodoo’ sometime after the end of the Civil War. “The Hausas…are still firm believers in witchcraft and attribute to certain people the power of casting spells and causing their victims to sicken and perhaps die.” (73). Certainly, the belief in hoodoo in the Southern states was rife in the early part of the 20th. Century; as Hyatt’s female informant from South Carolina implies. This was true for nearly all blacks and half the whites south of the Mason/Dixon line. Reaching back into slavery times especially in Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina.

Fast forward some 34 years and one of

only two titles by Ruby Paul is listed as Last

Farewell Blues [Paramount 12592]. Recorded about

the end of 1927, she is accompanied by an unidentified pianist (nice but

superfluous to this performance) and the harrowing poignancy of the slide guitar

played by Bobby Grant.

The lyrics get even more lachrymose

(a-typical in early blues) so it is not surprising to discover that along with

another title by the Unique Quartette from the same 1893 session, Maid Of The

Mill, both were “standard white parlor songs”

(78).

It is quite likely therefore, that the above-quoted verse

from Last Farewell Blues was included in the 1893 song by the Unique

Quartette featuring the ‘crossing verse’.

Johnson being one of a ‘select’ group of blues singers who never recorded a sacred title; along with ‘wild’ artists such as Lucille Bogan, King Solomon Hill and Kokomo Arnold. However, on his Stones In My Passway [Vocalion 03723] in 1937, Robert Johnson invokes a more ‘unholy’ and much earlier icon from the spirit world of ancient gods and vodou/hoodoo. He included the phrase:

When a ‘re-discovered bluesman (Son House?) in the sixties was played this recording he expressed disbelief that the record company, ARC, actually issued this song, in 1937. So he readily recognized the blatantly sexual content even though Johnson’s phrase does not appear on any other blues-as far as I’m aware. This leads us once more into the world of spirits, ancient gods and goddesses. A group of spirits called the Sidhe are ‘Fairy’ or ‘Fairies’ “(the word is singular and plural)” (83) who inhabited Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. A ritual from the latter “encourages bribing the Sidhe to save lives via the crossroads.

A three-way crossroads is usually referred to in the UK as a ‘T-Junction’. It is not a long journey from the three-legged stool to the sexual symbol per se as used by Robert Johnson.. Traveling right back to Ancient Greece we find the Olympians’ god Hermes. He “is the trickster of the crossroads,…summon him by erecting a herm or cairn of stones, especially at a four-way crossroads (x-shaped).” (85)Judika Illes also notes “Statues called ‘Herms’ were used to portray him: tall rectangular pillars displaying his head on top and his erect penis sticking out. Herms were placed at crossroads.” (86) Although later shown as a winged messenger of the gods, Hermes’ “most ancient images portray him in the form of an erect phallus.” (87) Hermes was later adapted in Haiti (from West Africa) as Papa Legba, the ‘Keeper of the Crossroads’. He is the first lwa or vodou spirit to be contacted in ceremonies so that other lwa can be reached. He is symbolized as “Number 3 (two legs and a phallus)…In Africa, he is sometimes venerated in the form of a phallus.” (88) From Spain “A Basque spell suggests,…that should illness arise without obvious reason or cause, someone should bring a cauldron to a crossroads, place a comb inside the pot together with some stones, and turn the cauldron upside down. This serves as a signal to witches that healing action is required and allegedly assistance will soon arrive.” (89) A prime candidate for the basis of Stones In My Passway. Also this spell has three elements: cauldron, comb, and stones; a popular requirement in Hoodoo, the Southern US adaptation of Vodou, when making mojo hands. This spell also invokes slavery times when slaves stole away at night to an arbor to sing and pray, and used an upturned pot to ‘capture’ the sounds so as not to be heard at the Big House by their ‘master’ the white slave –owner. The four-way crossroads referred to above are usually associated with male spirits while “In general, three-way crossroads are associated with female spirits.” (90) As Illes says: “The most common variety are three and four-way crossroads.” (91) Crossroads are the most powerful location for spirits generally speaking and some are crossroad specialists such as Hermes and Eshu-Elegbara (Papa Legba). Another is the Greek goddess Hekate/Hecate. These spirits are also known as ‘Crossroads Spirits’ or ‘Gatekeepers’. “ Sometimes they’re called ‘Road Openers’ too.” (92) Hekate is also known as “Hecate Trivia…’Trivia’ literally means ‘three roads’.” (93) From the foregoing it is readily apparent that Robert Johnson was alluding to a three-way crossroads when he included his ‘three legged truck-on’ phrase on Stones In My Passway; that is to say at a crossroads where female spirits congregate. Particularly Hekate: “Hecate’s image was once placed in Greek towns wherever three roads met.” (94) i.e. a ‘T’ or a ‘Y’ junction. It would seem that on his other take of Crossroad Blues Johnson is alluding to the ’T’ variety.

The main highways through Mississippi

in the 1930s: 49,51, and 61, ran north to south and as Johnson did not list an

option to look in either direction of these major points of the compass it must

be assumed he was at a ‘T’

or three-way crossroads with east or west his only options to travel (unless he

retraced his steps from whence he came). Surely, in his mind loomed Hekate

“Queen of the Crossroads”

and “The Most Lovely One…Three

Headed Hound of the Moon…Light Bringer.”

(96)

A clear connection to Cerebros the three-headed hell hound

guard dog in Hades (aka Hell) and another ‘devilish’

subject in Johnson’s repertoire on Hellhound On My

Trail [Vocalion 032623] in 1937. Returning to the world of hoodoo (p.16)

another of Hyatt’s informants gives an unusual alternative use of the black cat

bone

The last line could be translated as: compared to the all-powerful and all-sexual Lilith, Johnson is saying his own earthly lover isn't even in the frame. While the first two lines and the bird references sit well with the Queen of Demons. She originated in Sumeria and “The Sumerian Burney Plaque, (circa 2,300 BCE) is generally identified as Lilith. It depicts her as a winged naked bird woman holding the ring and the rod of power and flanked by owls. Her taloned feet stand atop reclining lions.”(103) In one interpretation from the Jewish Bible (and the King James version) she is indirectly referred to as a “screech owl.” (104) Lilith possesses many forms. As “an old crone or beautiful young woman. She may appear as a woman from head to waist; flame underneath.” (105) She also adapts to animal shapes “typically as a large black cat, black dog or owl. Even when in human form, Lilith may display bird’s feet, claws or wings.” (106) Johnson’s song invokes spirits who make him impotent (‘lost appetite’) and bring on the menstrual cycle in a woman (‘please don’t block my road’) – one of the female states most feared by otherwise macho men.

If, in his Crossroad Blues, (see above) everybody did indeed pass him by and the old Hausa belief came true; then the closing lines of Me And The Devil Blues [Vocalion 04108] would seem to be a logical result.

And his opening two verses a [super]natural progression.

Referring to the Protestant Reformation (c.1517) in the Medieval Period, Paine writes: No period in Christian history was even [sic] so beneficial to the Devil. He had advocates on both sides, including Martin Luther, who wrote in his Tishreden that, ‘Early this morning when I awoke the fiend came and began disputing with me. “Thou art a great sinner”, said he. I replied, “Canst not tell me something new, Satan?” (110) Although the Devil/devil appears in many blues lyrics Satan is very nearly totally absent. Johnson’s usage in Me And The Devil Blues seems to be pre-empted by a 1934 recording from guitarist Bob Campbell Worried All The Time [Vocalion 02798]. An excellent heavy-voiced singer Campbell appears to shun the Devil rather than accept his company, blaming Satan for his own mistreatment meted out to the woman he loves.

Bob Campbell reflects a more casual religious reference with the exclamation ‘Lord’ akin to Robert Johnson’s appeal to God in Crossroad Blues.

The earliest known crossroads in the

South that has come down to us is situated in what was known as ‘Indian

Territory’ prior to 1907. In that year the state of Oklahoma was born. With

the arrival of the M-K-T railroad or ‘Katy’ in 1872 this formed the first rail

crossing in the Southern states. The station/depot was named McAlester. But

before this date the locality was simply known as the ‘Cross Roads’. This was “where

the Texas Trail from Springfield, Missouri, to Preston and Dallas crossed the

California Trail from Fort Smith to Albuquerque”.

(112)

The story is told by one J.L. McAlester in later years how he

happened on an old “memorandum book” written long before the Civil War by

a geologist which included the entry that “the best coal was to be found at

the ‘Cross Roads’.”

(113) As the said geologist had been part of “a

government exploring party” at the time, McAlester took it to be authentic.

He therefore “went to the ‘Cross Roads’ where he established a store and soon

became the owner of a flourishing business. By his subsequent marriage to a

Chickasaw girl he became entitled to citizenship in the Choctaw Nation. When

the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas

Then crossing the state line from Texas into Oklahoma, Henry Thomas rode the Katy over that very same crossing in what he still called the ’Territory’

Then on into St. Louis where he “changed cars” once again as he headed up to Chicago, to cut another recording session for Vocalion Records. This ‘first’ rail crossing saw the Katy cross the old Atlantic & Pacific - later the Frisco. Both the Katy and the Frisco were popular railroads in the annals of the early blues. This just might be the subject of Katy Crossing Blues by Texas Alexander in 1934 at a session in Fort Worth, Texas. The crossing appears in relatively few Blues recordings. This includes a small group which featured some variants of the verse:

Not surprisingly, since the Katy’s early arrival in the state, the first blues to include examples of what was essentially a ‘floating verse’ emanated from Texas singers; or ones closely associated with Texas. Pianist Texas Bill Day recorded (as ‘Will Day”) his Central Avenue Blues [Columbia 14318-D] in April, 1928, down in New Orleans.

Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943

(B. & G.R.) list the accompanist as unknown

clarinet

Table A

Of course the most famous crossing in

the Blues which was also a railroad crossing, is ‘where the Southern cross the

Yellow Dog’ at Moorhead in the Mississippi Delta. This has been discussed at

some length

This leaves a couple of spoken asides in 1930 by Mississippi’s Bukka White who as a Delta guitarist, then barely 20 years old, accompanied an older singer Napoleon Hairiston probably also on guitar; on a series of mouth-watering titles of which only four were issued. One of these was New Frisco Train [Victor 23295] where Bukka imitates the train sounds on his ferocious National steel guitar, including the clanging bell as the train slows for the crossing. Although he does not sing Bukka makes all the spoken asides except two. One is by Hairiston and one by an unidentified third man who makes the “Vicksburg in the cool of the evenin’” comment. Said Mr. White:

Referring to a favoured Mississippi

town (Itta Bena) his comments point up another vital role of the

crossing/crossroad- as a pick-up place for aspiring hoboes including of course

the blues singers.

Important too was a further role as enacted by travelling

railroad circuses. Starting in 1868 they had always unloaded at the crossing

and re-loaded there at the end of a visit to a particular town or city. Indeed,

the preceding procession (to the show) started from this point wending its

majestic way into town.

Table B

In fact, only the C.A. Tindley Bible Class Singers refer to a railroad! The others concern a funeral except the Merline Johnson song which is a warning against falling in love, too quickly. In any event the crossing/crossroad is a major icon in the Blues and has roots going back to the days of slavery. As an interesting footnote, the earliest links between black men/spirits and the crossroads I have come across to date are from Kilkenny in Ireland c. 1320. Lady Alice Kyteler was accused of renouncing Christianity “to sacrifice roosters and peacocks at crossroads to a spirit named variously ‘Robin’ or ‘Robert Artisson’ or Filius Artis’. This shape-shifting spirit was allegedly Lady Alice’s familiar, sometimes appearing as a cat or a large shaggy dog or sometimes a huge black man accompanied by two tall dark companions carrying iron rods. Robin is described in records as ‘Aethiopis’ or ‘negro’. [sic]”. (122) Adding further to this snapshot of the14th. Century, Lady Alice had a “maid-servant” Petronilla de Meath who “claimed that Lady Alice, the most powerful witch in the world, had taught her sorcery and witchcraft. She said she saw Lady Alice’s demon manifest as not one, but three black men, who each had sex with Lady Alice. Petronilla acknowledged that she herself cleaned the bed.” (123) Lady Alice could be an off-shoot or avatar of Lilith.

The dark shadow of slavery times and the coffles now seems to invade Robert Johnson’s famous Crossroad Blues. A harrowing description of a coffle is quoted in Slave Testimony. An informant relates what her mother told her-going back into slavery days when she learnt she was being sent South down to Georgia. The next morning but one we started with this Negro trader upon that dreaded and despairing journey to the cotton fields of Georgia. Mother has often told me of the heart-breaking scene. A long row of men chained two-and-two together, called the “coffle”, and numbering about thirty persons, was the first to march forth from the “ pen”; then came the quiet slaves—that is, those who were tame in spirit and degraded; then came the unmarried women, or those without children; after these came the children who were able to walk; and following them came mothers with their infants and young children in their arms. This “gang” of slaves was arranged in travelling order, all being on foot except the children that were too young to walk and too old to be carried in arms. These latter were put into a waggon. But mothers with infants had to carry them in their arms; and their blood often stained the whip when, from exhaustion, they lagged behind. When the order was given to march, it was always on such occasions accompanied by the command, which the slaves were made to understand before they left the “pen”. To “strike up lively”, which means that they must begin a song.

Oh! what

[sic] heartbreaks there are in these crude and simple

songs! The purpose of the trader in having them sung is to prevent among the

crowd of negroes who usually gather on such occasions, any expression of sorrow

for those who are being torn away from them; but the negroes, who have very

little hope of ever seeing those again who are dearer to them than life, and who

are weeping and wailing over the separation, often turn the song thus demanded

of them into a farewell dirge. The following song may be taken as a specimen:”.

(124)

This dirge called The Coffle Song as seen in print,

can only convey little more than a hint at the unbelievable emotional trauma

racking the very souls/psyche of these people as they tramp painfully and

wearily (if they survived!) toward the auction block at the next crossroads.

Walter Johnson, again, noted that cities which had slaves in holding pens before dispensing them further south included St. Louis in Missouri. As well as elsewhere: “Slaves were gathered in Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, Norfolk, and St. Louis and sent south, either overland in chains, (the coffle) by sailing ships around the coast, or by steamboats down the Mississippi. These slaves were sold in the urban markets of Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, Natchez, and especially New Orleans”. (126) The Coffle Song is more than likely a direct precursor of a gospel number which featured on many early recordings, especially in the 1920s, usually titled Do Lord, Remember Me. The earliest recordings listed were in 1924 when two versions were made by the Fisk University Jubilee Singers/Quartet for Columbia but remain unissued. One of several later ones appears as the very antithesis of the mournful Coffle Song. Taken at a fast clip the downhome sounds of the fine Miles Bros. Quartette in 1937, included just three verses as couplets, drive the rhythm along with the repeated chorus.

Another version of this number, at a similar tempo, was made some two months later by the Golden Eagle Gospel Singers with unidentified guitar, fiddle, and tambourine driven along by Josephine Tillman’s rich vocals. But the most compelling recording of Do Lord Remember Me that has yet come to light, has to be the Library of Congress side made in 1936 by Jimmie Strothers and Joe Lee. Once again the upbeat tempo is maintained as Tony Russell put it: while he played his guitar conventionally, another man [Joe Lee] beat on its neck with wires. (128) Together with their twin vocals (one heavy, one light) they impart an almost ferocious rhythm which has rarely, if ever, been surpassed. Although fragments of this and of other well-known gospel songs appear in the sermons of some recorded preachers in the 1920s and ‘30s, only two cut titles using variants of Do Lord Remember Me. One by Deacon Leon Davis in 1927 with a slightly different tune and another by Rev. McGhee (the less well-known one to collectors) in 1942 for the Library of Congress in Clarksdale, Mississippi, which has yet to be reissued. This song, and no doubt many variants, would be sung by the unfortunate slaves when leaving the auction block to be shipped south. One of the most graphic accounts of this horrific leaving/parting scene was captured by post-war bluesman Johnny Shines in 1974, invoking the description on a steamboat by Abraham Lincoln back in 1841 (see above). Born in Frayser, Tennessee, in Shelby County, on 26th. April, 1915, Shines was a powerful singer who was best-known for his Delta-style blues which were often accompanied by his superb slide guitar-playing. Also famous for having “run with” Robert Johnson in the mid-1930s (129) – especially in East Texas – Johnny Shines was unusual within the genre insofar as he took a great interest in his own historical and traditional roots. His lengthy spoken introduction with occasional guitar to his version of Do Lord Remember Me (called Goodbye) is an invaluable insight into not only this particular song but also the often stark reality of slavery from the sharp end, in the southern states – the Peculiar Institution.

Johnny Shines then sings a version of Do Lord Remember Me re-titled as Goodbye. A close cousin to this song is one usually called Take A Stand and is represented by only two or three early recordings using the title. In 1928 Elder McIntorsh and Bessie Johnson lead the fiery singing and the celebratory shouts [on OKeh 8671] and include one verse harking back to The Coffle Song.

The following year Blind Willie Johnson set down Take Your Stand [Columbia 14624-D] although he sings “take a stand”. While he employs his false bass vocal throughout, he discards the slide and Willie B. Richardson is right on with her responses; and yet the overall effect is somewhat subdued after listening to the McIntorsh and Edwards performance. This is the case even when compared to Johnson’s own frenetic I’m Gonna Run To The City Of Refuge [Columbia 14391-D] also without slide guitar, for example. But he adds something more in the way of specific advice to those being left behind, when he sings “preach the word” and “run the race” (132) covering both sacred and secular attitudes to life ahead. In the same year Blind Willie Johnson recorded his Take Your Stand (1929) the King of the Delta Blues-Charley Patton- cut a remarkable two-part gospel side Prayer of Death for Paramount Records. Reported as a stream of consciousness performance Patton presents what amounts to a ‘religious rag’. Several fragments of different well-known gospel songs all accompanied by the same accompaniment. Much the same as Henry Thomas would on secular numbers. Charley Patton’s haunting slide guitar ‘talks’ and ‘prays’. On Prayer Of Death-Pt.1 [Paramount 12799--] he includes a snatch of Take A Stand, perhaps likening this traumatic separation to the death of loved ones, where his guitar often completes a line. His opening spoken introduction seems to be setting him in the right spirit or mood:

Significantly, Charley Patton’s anger at the situation originally depicted in The Coffle Song might have led him to include two less common verses:

And his fury at the ‘auction block scenario’ with the resulting aftermath in Patton’s own time, being even more explicit in what has to be unique to the Delta blues king:

The song Do Lord Remember Me made a brief, if sometimes indirect, visit to the Blues. In 1929, a St. Louis-based guitarist Clifford Gibson adapted the ‘If I never’ verse on his Levee Camp Moan [Victor 38577]

Texas blues man Little Hat Jones featured a variant of the song omitting the title phrase, which he called Bye Bye Baby Blues, [OKeh 8815] in 1930. While fellow Texan Henry Thomas used the song’s refrain when he cut Charmin’ Betsy [Vocalion 1468] also in 1929. This had been recorded several times in the old timey/hillbilly catalogue (135) commencing in 1925. Betsy also included parts of an old country song Coming Round The Mountain which was also popular in the UK by the late 1940s. But in 1927 on The Fox And The Hounds [Vocalion 1137]Thomas secularises the theme (and the title phrase) completely.

Some 14 years later, Tennessee’s Son Bonds took the last line in the Henry Thomas song and adapted it to the refrain of Black Gal Swing [Bluebird B8852]

This features the upbeat rhythm imparted by the Delta Boys and some of the most inspired(?) kazoo playing since Ben Ramey (of the Memphis Jug Band) in the 1920s, by Bonds himself. But despite the raucous and infectious atmosphere, Black Gal Swing has that underlying current of horror, fear, and anger at the blacks’ past suffering in the slave coffles and on the demeaning auction block; which gave birth to The Coffle Song and ultimately contributed greatly to the Blues. Conclusion The Coffle Song is essentially a secular one with only the ‘I’ll pray for you when I rest’ line and the last verse having any religious reference. Akin to Robert Johnson’s ‘maverick’ line: “Lord, have mercy, save poor Bob if you please”. in his Crossroad Blues. Also Worried All The Time by Bob Campbell could be cited. His “Lord, I’m worried, stays worried all the time” is more of an exclamation of sadness tinged with anger; than to do with religion. Sometimes a blues was adapted from a ‘sacred’ song, as the Delta Boys illustrate; my claim for a secular origin notwithstanding! Tunes and song structures freely crossed the line between secular and sacred song performances. Indeed, in the colonial and early antebellum periods no such line seemed to exist for the slaves. A spiritual was sometimes used as a boat song for example. It wasn’t until the closing decades of slavery prior to the Civil War, that the ‘separation line’ between the two became more strictly observed.

This situation, especially given the

more cavalier outlook in the South on Christianity prior to the ’Great

Awakening’ in the mid-eighteenth century, probably stretches back to the very

beginnings of the North American slave system; or Peculiar Institution as it was

known in its dying days. In fact commencing not long after the arrival at the

James River of the first boatload of African indentured servants in 1619. An

extract from an observation during this initial period makes fascinating

reading. About 1625 at Cape Cod (later in the state of Massachusetts) Captain

Woolaston “takes a great part of the servants and transports them to Virginia”

(138)

His associate, one Thomas Morton, seeking to take over the

new colony at Cape Cod and re-locate it, plied the inhabitants with drink and

convinced them (when the Captain was away on one of his Virginian trips selling

on servants): “ ‘You see,’ saith he, ‘that many of your fellows are carried

to Virginia, and if you stay…you will also be carried away and sold for slaves

with the rest.”.

(139) Although these servants would presumably

have been white colonists, it does point up the fact that slavery had taken hold

in the future U.S.A. less than 20 years after that fateful boatload’s arrival in

1619. It is hardly likely that these ’new’ slaves would not have included black

as well as white indentured servants (who were often treated as cruelly as the

Africans

It seems to be from the period I have suggested (1840s and 1850s) that the attitude towards some secular songs expressed by many ex-slaves, in interview during the first half of the 20th. Century, became so abhorrent to ’evil ditties’ and especially those corn shucking songs - a major secular root of the Blues. ADDENDA 1 The foregoing article on ‘Coffles & The Auction Block’ is, as stated at the beginning, part of a far larger work seeking out the secular roots of the Blues. The collective undertaking for this is: Rex Haymes, Alan White, Robin Andrews, Dai Thomas, and Max Haymes. Work is in progress on not only tracing corn shucking songs (although thought to be a major factor) but a broader spectrum including work songs, generally. As on the rivers and of course sometime later on the Southern prison farms. To give some idea of the vastness of this project, detailed below is an initial ‘shopping list’ of avenues to be explored:

To name but a few! Fortunately, I have some work done in a few of these areas amassed over the years, including: sea shanty links, vaudeville-blues, hoodoo doctors, preachers, steamboats, etc. But this in many instances needs to be greatly enlarged. ADDENDA 2 A survey of other origins (apart from the biblical one) of Do Lord Remember Me, including music scores from 1867, is also in progress. As well as taking us back to the 16th. Century; the earliest (to date) reference to the coffles in what was later the USA for example. And the earliest written record (in the American colonies) alluding to patting juba. Max HaymesNovember, 2009.

Discographical details from Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943 (4th. ed. Revised). Robert M.W. Dixon. John Godrich. Howard Rye. [Clarendon Press. Oxford.] 1997. Post-war discographical details from Mike Leadbitter. Notes to Country Blues L.P. Xtra 1142. 1974. Transcriptions, corrections and additions by Max Haymes. This article was transcribed

from the original text and re-formatted

for the earlyblues.com website by Alan White, March 2010

Website and Photos © Copyright 2000-2010 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Of course these

roots will also include references to black sacred music

Of course these

roots will also include references to black sacred music

Given

the oral tradition of the African American since slavery days, the sight of

these black camels in the later 19th. Century surely invoked memories

of horror and death, passed on down by their forebears. The art of the black

preacher was to communicate as well as proselytize. More of a chanting

preacher, Rev. J.M. Milton knew how to hold the attention of his black

congregation.

Given

the oral tradition of the African American since slavery days, the sight of

these black camels in the later 19th. Century surely invoked memories

of horror and death, passed on down by their forebears. The art of the black

preacher was to communicate as well as proselytize. More of a chanting

preacher, Rev. J.M. Milton knew how to hold the attention of his black

congregation.

Coincidentally

(?) The Black Diamond train

Coincidentally

(?) The Black Diamond train  This association

of the slave auction block and coffles with crossroads could well explain the

dearth of references to them in the blues. One of the very few I have come

across is Charley Patton

This association

of the slave auction block and coffles with crossroads could well explain the

dearth of references to them in the blues. One of the very few I have come

across is Charley Patton Interestingly, the

first recorded reference to a crossing, if not the crossroad itself, could well

have appeared as early as the autumn/fall of 1893! The earliest black quartet

that we know of started their extensive group of recordings in 1890 on December

19, in New York City.

Interestingly, the

first recorded reference to a crossing, if not the crossroad itself, could well

have appeared as early as the autumn/fall of 1893! The earliest black quartet

that we know of started their extensive group of recordings in 1890 on December

19, in New York City.

Even more awesome

is one of the most powerful spirits in Jewish folklore and one of the most

popular in the world of 2009-Adam

Even more awesome

is one of the most powerful spirits in Jewish folklore and one of the most

popular in the world of 2009-Adam