|

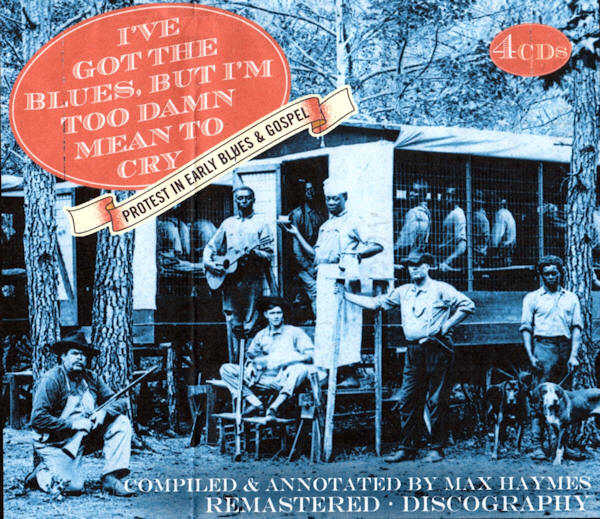

This is the full essay soon to be published in short form as the liner

notes for 'I've Got The Blues, But I'm Too Damn Mean To Cry'

on

JSP Records

4 CD boxed set (see the Discography below). We hope you all enjoy it.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The word

‘protest’ in the 21st. century is often linked with, and

refers to ‘political protest’. But this is really a tautology or

two words strung together meaning the same thing. Erroneously,

people refer to being political as involvement by a group, or party,

retaining power of government or aspiring to acquire this power for

themselves.

But

politics is a much broader concept. It covers virtually

everything in our daily lives from birth to death. Public

health and safety, education, transportation, energy, agriculture,

social and environmental issues, are major aspects governing the

degree of quality we experience in our time on the planet. Indeed,

for African Americans in the first 3 centuries of enslavement,

politics and protest meant life itself. While the former spent

much time talking of what could be achieved, the latter attempted to

have this talk transformed into action.

This

4-CD set is concerned with the broader concept. Necessarily

so, as blacks in the US were often denied access to ‘politics’,

certainly into the 1950s. Apart from a brief spell during

Reconstruction after the Civil War until the Hayes Compromise in

1877, which resulted in returning power to whites in the South and

the withdrawal of Federal troops; in exchange for the Southern vote

in the coming presidential election. By the turn of the 20th.

century blacks were completely disenfranchised. Given the

ever-present real danger in the racial set-up of ‘Jim Crow’, it is

quite understandable that the earlier blues singers did not concern

themselves too much with politics-even where they might have done. This

4-CD set is concerned with the broader concept. Necessarily

so, as blacks in the US were often denied access to ‘politics’,

certainly into the 1950s. Apart from a brief spell during

Reconstruction after the Civil War until the Hayes Compromise in

1877, which resulted in returning power to whites in the South and

the withdrawal of Federal troops; in exchange for the Southern vote

in the coming presidential election. By the turn of the 20th.

century blacks were completely disenfranchised. Given the

ever-present real danger in the racial set-up of ‘Jim Crow’, it is

quite understandable that the earlier blues singers did not concern

themselves too much with politics-even where they might have done.

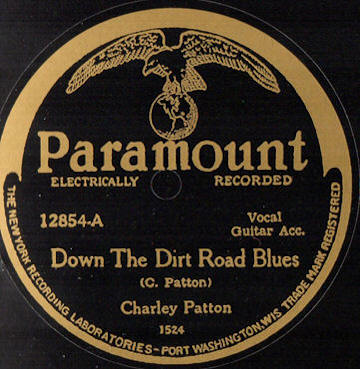

When the great Charley Patton sang “Every day

seem like murder here” (1)

he was quite likely referring not only to his home state of

Mississippi but the whole of the USA as well! By his inclusion

of the following verse, he is protesting that he’s got the ‘Overseas

Blues’ because he is unable to leave the US to go and live overseas

in say France or England, which were far less concerned about the

colour of a person’s skin and no doubt supported by glowing stories

from returning black soldiers at the end of WW I.

| |

Some people say them Overseas Blues

ain’t bad. |

|

Spoken: |

Of course they are! |

| |

Some people say them Overseas Blues

ain’t bad. |

|

Spoken: |

What was a-matter wid em? |

| |

It must not-a bin them Overseas Blues

I had. (2) |

Rare indeed, are the words appearing in the

Memphis Jug Band’s version of He’s In The Jail House Now.

[Victor 23256].

| |

I remember last election; (Yeah!) |

| |

Jim Jones got in action. (Uh-huh!) |

| |

Said he’d vote for the man that paid

the biggest price. |

| |

|

| |

Next day at the poll; |

| |

He voted with heart an’ soul. |

| |

But instead of voting once, he voted

twice. (Uh-huh!) |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

He’s in the jailhouse now; |

| |

He’s in the jailhouse now. |

| |

Instead of him stayin’ at home; |

| |

Lettin’ these white folks’ business

alone. (Why’s that, now?) |

| |

He’s in the jailhouse now. (3) |

| |

|

This appears unique as an explicit protest

against the white ruling political regime, in the whole of the

pre-war blues era (1890-1943). The Memphis Jug’s vocalist also

has a dig at police corruption.

| |

You remember Henry Crew? |

| |

That sold that no-good booze. |

| |

He sold it to the police on the beat. |

| |

Now, Henry’s feelin’ funny; |

| |

Police give ’im marked money. |

| |

He’s got a ball an’ chain round ‘is

feet. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

He’s in the jailhouse now. etc,

(4) |

Elsewhere in this song, Charlie Nickerson

includes the lines:

| |

If he’s got a political friend; |

| |

Judge [‘s] sentence he will suspend.

(5) |

The only reason the MJB got away with this song

(I suspect) was due to their huge popularity with both blacks and

whites in the Memphis area and even the city’s puritanical Mayor

Crump who would check the group out, on Beale Street sometimes.

More often than not, any protest in the early

Blues was cloaked in one or more levels of meaning or aimed at ‘a

substitute’ which ultimately attacked white people from whom many

blacks received bad treatment. This was generally a

misbehaving partner in a failing relationship. Or a member of

a train crew who were blamed for ‘taking my baby away’, and

sometimes the train or railroad itself became the target. Like

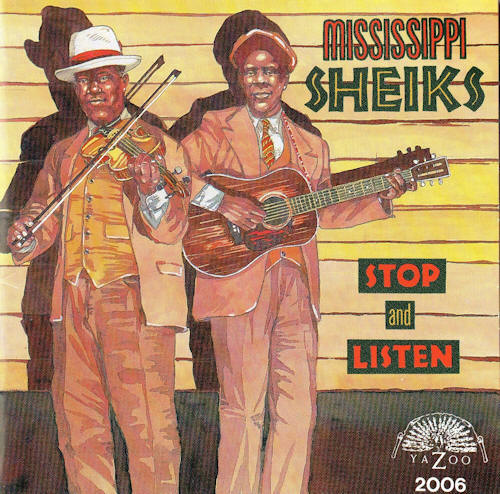

Charley Patton, the Mississippi Sheiks were also from the Magnolia

State.

Cover of Yazoo CD of Mississippi Sheiks. 1992. L: Lonnie Chatmon. R:

Walter Vinson.

By Frederick Carlson

Probably the most famous string band in the South, they usually

recorded featuring two or more rarely three musicians. Immensely

popular with both black and white audiences alike, they cut a lot

of their sessions in the state of Texas. Their brand of Blues was

in complete antithesis to the harsh, deep-felt music of Charley Patton.

On their Jailbird Love Song [OKeh 8834] in 1930, Walter Vinson on

vocal takes a gentle dig at the white old timey (otm) singers with a

very creditable yodel. More in-depth are the words in this song,

accompanied by a second singer, Bo Carter. Delivered in raffish

manner, nevertheless the target is the injustice towards blacks by white

police officers. In this case wrongful arrest, simply based on the fact

the subject was black as well as being a stranger. Not obviously, but

protest all the same.

|

1. |

When I was a rounder, I stopped in

New Orleans; |

| |

I was a great long way, the way from

home; I didn’t know nobody that I seen. |

| |

|

|

2. |

I was walkin’ along the street one

day. I didn’t mean no harm; |

| |

The police looked up an’ they seen me

an’ they began to make their alarm. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

Now, ain’t it hard? Ain’t it hard? |

| |

Just lookin’ through the bars. |

| |

The police looked an’seen me an’ they

began to make their alarm. |

| |

|

|

3. |

They seen I was a stranger. They

pulled down on my trail; |

| |

Soon as they had me surrounded, they

carried me to the city jail. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

Now, ain’t it hard? Ain’t it hard? |

| |

Just lookin’ through the bars. |

| |

Soon as they had me surrounded, they

carried me to the city jail. (6) |

Even before the unfortunate kidnapped Africans

arrived on American shores, music and protest ran hand-in-hand.

This involved a young woman “who was likely an Iglo speaker,”.

(7)

So, it was related: “When the young woman came aboard the

Liverpool slave ship the ‘Hudibras’ in Old Calabar in 1785, she

instantly captured everyone’s attention. She had beauty,

grace, and charisma: ‘Sprightliness was in her every gesture, and

good nature beamed in her eyes.’ When the African musicians

and instruments came out on the main deck twice a day for

‘dancing’, the exercising of the enslaved, ‘she appeared to great

advantage, as she bounded over the quarter-deck, to the rude strains

of African melody,’ observed a smitten sailor named William

Butterworth. She was the best dancer and the best singer on

the ship…Captain Evans gave her the name Sarah.”.(8)

This is the first instance I have come across a

definite reference to slaves on board with instruments and

definitely the first time a particular slave found so much attention

from white observers. ‘Sarah’ becomes, just for a moment, a

vibrant and very human being! Rediker continued: “Sarah

survived the Middle Passage [and] She was sold at Grenada,

with almost three hundred others, in 1787…When she went ashore she

carried African traditions of dance, song, and resistance with

her.”. (9)

Sarah had become one of Captain Evans’ ‘favorites’ even though

suspected of a bloody revolt whilst still on his ship. It

transpired that both Sarah and her mother (also on the ‘Hudibras’)

“not only knew about the plot, they had indeed been involved in it.

Sarah had likely used her privileged position as a favorite,

[probably via coerced sexual ‘favours’ to Captain Evans] and her

great freedom of movement that this entailed, to help with planning

and perhaps even to pass tools to the men, allowing the men to hack

off their shackles and manacles.”. (10)

Alan Lomax, writing in 1992, stated “the blues

[is] the first satirical song form in the English

language—mounted on cadences that have now seduced the world.”.

(11)

He also claimed that the griots, ancestors of the blues singer, from

West Africa such as “the virtuosic bards of Senegal, accompanying

themselves on complex stringed instruments backed up by rhythm

orchestras, still play a leading role in the life of many West

African communities. They are social satirists whose verses

once on a time dethroned chieftans.” [sic] The

bluesmen of the Delta continued this satiric tradition, depicting,

as far as they dare, the ills and ironies of life in their

caste-ridden society.”.

(12)

In Sam Charter’s pioneering book The Country

Blues in 1959, he quoted lines of the most simple eloquence,

with a hard-hitting punch, around the turn of the 20th.

century when the Blues had only recently emerged as a recognizable

form. Indeed, an adaptation of these lines form the title of this

set for JSP Records.

| |

I got de blues, |

| |

But I’m too damn mean to cry. (13) |

Lomax used a variation in his Land Where The

Blues Began.

| |

I got the blues and I’m too damn mean

to cry; |

| |

I got the blues and I just can’t be

satisfied… (14) |

These lines, slightly toned down, appeared

in the unlikely shape of an early vaudeville blues title in 1921.

This was I’ve Got The Blues But I’m Just Too Mean To Cry [Arto

9110] by Dorothy Dodds; one of only five recordings she made.

Yet as David Evans said, Ms. Dodds “shows that she was the equal

of any of the other blues singers that recorded in 1921,” (15)

She includes a cool slice of early rap:

| |

You all see tears in my eye; |

| |

I cry so much that I gone dry. |

| |

The way the boys give me the slip; |

| |

Someone would think I had the grippe.

[aka influenza] |

| |

A good man now, is hard to find; |

| |

But I’d be satisfied with any kind. |

| |

All night long I sit an’ fret; |

| |

I’m like a rainy day an’ that’s all

wet. |

|

Ref: |

Because I got the blues, but I’m just

too mean to cry. (16) |

But sometimes frustration and anger at the

powerless situation blacks had to endure under the ever-present

racialist regime known as ‘Jim Crow’, in the first decades of the 20th.

century, could not always be contained in symbolism or multi-layer

of meaning. This naturally led to violence in some lyrics of

the Blues and its forbears. A well-known example occurs

in the legend of a notorious black outlaw from the 19th.century,

(in Alabama) known as ‘Railroad Bill’ (aka Morris Slater). A

variant reappeared in the mid-1950s in the British skiffle revival:

| |

I’ve got a .45 pistol on a .38 frame, |

| |

How can I miss when I’ve got dead

aim. |

The second line had appeared in a Butterbeans and

Susie song ‘Bowlegged Papa’, and shortly after Ida Cox used these

words as a title on Paramount in 1925. Some 4 years later Will

Bennett made the only black commercial recording of ‘Railroad Bill’.

(see Vaudeville Blues. 4-CD set. JSP 77161 for these

recordings.) in the pre-war era. It contained another

verse which was not often used by the British skiffle heroes.

| |

Buy me a gun just as long as my arm; |

| |

Kill everybody ever done me wrong.

(17) |

This verse appeared in several other early blues,

not related to ‘Railroad Bill’. Although Will Bennett sings of

taking a stand on a mountain top with a ‘.41 Derringer in my right

an’ left hand’ his angry words seem almost benign in comparison to a

vaudeville blues record called Mad Mama’s Blues [Edison

51477] where Josie Miles surely reflected the pent-up feelings

of rage and indignation experienced by blacks over many years of

blatant oppression. [It is significant that in the

earlier 20th. century nearly all the race riots in the

South were started by whites.

Until, in

fact, the 1966 riot in Watts,

California].

| |

Gonna set the world on fire; |

| |

That is my one mad desire. |

| |

|

| |

I’m a devil in disguise; |

| |

Got murder in my eyes. |

| |

|

| |

Now, I could see blood runnin’

through the streets. (x 2) |

| |

Could see everybody layin’ dead at my

feet. |

| |

|

| |

The man invented war sure is my

friend. (x 2) |

| |

Don’t believe that I’m sinkin’,

|

| |

just look what a hole I am in. |

| |

|

| |

Give me gunpowder, give me dynamite.

(x 2) |

| |

Yes! I’d wreck the city. Gonna blow

it up tonight. |

| |

|

| |

I took my big Winchester down off the

shelf. (x 2) |

| |

When I get through shootin’ there

won’t be nobody left. (18) |

Ad. in Sears

Roebuck cat. 1897

It might be that the great Texas bluesman Blind

Lemon Jefferson (see JSP 7706] was inspired by the Josie Miles song to

record his Dynamite Blues [Paramount 12739] some 5 years later.

But whereas Ms. Miles could ‘hide’ behind a claim of insanity, Lemon

directs all his anger at the safer target of a woman who threw him down.

| |

I feel like scrappin’, havin’ a great

big row; |

| |

I said I feel like scrappin’, havin’

a great big row. |

| |

Because the woman I love said she

don’t want me no how. |

| |

|

| |

She swore that she love me. I know

she doin’ me wrong; |

| |

An’ she swore that she love me, but I

know she done me wrong. |

| |

I’m gonna start somethin’, man, an’

I’m tellin’ you it won’t be long. |

| |

|

| |

The way I feel now, I could get a keg

of dynamite; |

| |

I say, the way I feel now, I could

get a keg of dynamite. |

| |

Put all in ‘er window an’ blow her up

late at night. |

| |

|

| |

I could swallow some fire, take a

drink of gasoline. (x 2) |

| |

Throw it up all over that woman an’

let ‘er go up in steam. |

| |

|

| |

I’m get in a cannon an’ let ‘em blow

me out to sea; |

| |

I’m goin’ get in a cannon an’ let ‘em

blow me out to sea. |

| |

Goin’ down with the whales, let the

mermaids make love with me. (19) |

It’s not hard to imagine that Lemon’s girl friend

is actually a much safer substitute as a recipient for what many

black people would like to do to whites who had treated them

unjustly and often brutally.

|

The

near-white looking

Bessie Tucker. 1928 |

But more often this ‘violent streak’ in the

Blues appeared almost fleetingly like a thin pencil of a sun’s

ray between fading dark clouds. Fellow Texan, Bessie

Tucker, with the power of Charlie Patton and the ‘field holler’

style of Texas Alexander; was apparently no stranger to the

harsher elements of the Southern prison system, if her

‘Penitentiary’, ‘Mean Old Master Blues’, and ‘Black Name Moan’

are anything to go by. On her ‘Key To The Bushes’

[Victor 23385] in 1929, the scene is part of the brutal

convict-lease system still so prevalent, in the 1920s. The

‘key’ she refers to is the Captain’s ‘big horse gun’ with which

she intends to escape the prison gang, probably killing the

white man in the process as revenge for the murder of her

partner ‘Sal’. As the sleeve note writer put it: “once

you hear her voice … A somber, even somewhat dangerous aura

comes immediately to the forefront.”

(20).

| |

I got the key to the bushes an’ I’m rarin’ to go.

(x 2) |

| |

I ought to leave here runnin’ but that’s most too

slow. (21) |

|

So she intends to take the dead Captain’s horse.

| |

Captain, Captain. Ha-aah-hahhh! What’s to [sic]

matter with Sal? (x 2) |

| |

You have worked my partner, [to death] you have

killed my pal. (22) |

Protesting the often vicious character of brutish

white, armed guards or ‘overseers’.

| |

Captain got a big horse pistol. Ahhhh-hah! An’ he think

he’s bad; |

| |

Captain got a big horse pistol. Hah-hahh! An’ he

think he’s bad. |

| |

I’m gonna take it this mornin’ if he make me mad.

(23) |

In 1933, Jack Kelly’s rasping vocal accompanied

by some blues-drenched fiddle from Will Batts, includes the

threatening line ‘ I got a 32-20 shoot just like a .45’ and

continues the ‘escape to the bushes’ theme. Using the

widespread term ‘Mr. Charlie’, for a white man.

| |

Ah! Mr. Charlie, you had better watch your men.

(x 2) |

| |

They all goin’ to the bushes an’ they are goin’

in. (24) |

The words of Bessie Tucker and Jack Kelly

refer to one of six general sectors of protest in early blues and

gospel—being ‘on the inside’ or imprisoned. Whether in a

convict-lease railroad gang, on a prison farm, the state

penitentiary, or in the jailhouse itself. Blacks were

routinely arrested by whites so as to use them for cheap labour and

to control ‘their Negroes.’ Many fine field recordings made by John

and Alan Lomax included more explicit protest from the Library of

Congress archives. One group of prisoners was led by Ernest

Williams who were on the Central State Farm in Sugar Land, Texas,

Fort Bend County. In 1933 they performed the haunting chant

Ain’t No More Cane On This Brazos [AFS 199 A1]. The Brazos

River snakes its way through East Texas down in Brazoria County,

emptying into the Gulf of Mexico; with a total length of 1050 miles.

The cane denotes the vast sugar cane plantations spreading across

the Texas lowlands.

| |

You

ought to come on the river in nineteen-four; |

| |

(Ohhh!-Ohhh!-Ohhh!) |

| |

You could find a dead man on ever’ turn row. |

| |

(Ohhh!-Ohhh!-Ohhh!) (25) |

And supporting the scenario ‘painted’ by Bessie

Tucker.

| |

You ought to been on the river in nineteen-ten; |

| |

(Ohhh!-Ohhh!-Ohhh!) |

| |

They rollin’ [working] the women, like they drive

the men. |

| |

(Ohhh!-Ohhh!-Ohhh!) (26) |

Another aspect of the ‘prison sector’ of black

protest concerned the often- invincible heroes such as Long John,

“a legendary character who outran the police, the sheriff, the

deputies with all their bloodhounds, and escaped from jail to

freedom.” (27)

Celebrated by many singers, including Papa Charlie Jackson on his

‘Long Gone Lost John’ in 1928, (see JSP 77184) and the earliest on

record by Stovepipe No.1 in August 1924 as ‘Lonesome John’; although

the singer refers to ‘Lost John’. [For a more

detailed discussion on ‘Long/Lost John’ see p.p.68-70. Songsters

& Saints.

Paul Oliver. [Cambridge University Press. Cambridge 1984]

Also in Texas, another prison group recording was made for the L of

C, led by Washington (‘Lightning’), to the accompaniment of swinging

axes. This was

Long John [LC:AAFS 13, AFSL 3 (L.P.)]. At least 9 verses

not quoted from the Rounder CD notes, are on the recording;

indicating that the song was far longer in live performance and

indeed does fade out. Some of which, due to space

restrictions, only a few can be quoted here. They include one

featured on the famous 1956 ‘skiffle’ [Skiffle

comes from the US back in the 1920s. Paramount issued a ‘Hometown

Skiffle’ in 1929 featuring some of their major blues artists

doing parts of their recordings as a promotional disc, to boost

sales of their output. British skiffle was largely made

up of home-made instruments, such as the tea-chest bass, washboard,

etc. First used of course in early blues.]

version cut by Lonnie Donegan in the UK. Having refused good

advice from his girl friend ‘Rosie’, Lightning ‘got to runnin’

around’ and ending up in the Darrington State Prison Farm.

Sung in the traditional black call and response

form, where the group repeat the leader’s line, this makes powerful

listening.

| |

First thing I know; |

| |

Well, I got in jail. |

| |

With a mouth poked out; |

| |

Well, now I’m in the pen. |

| |

An’ I can’t get out. |

|

Ref: |

It’s Long John; |

| |

He’s long gone. (x 3) |

| |

|

| |

Well-a

John made; |

| |

‘Is pair of shoes. |

| |

Well,

the funniest shoes; |

| |

That was ever seen. |

| |

Had a

heel in front; |

| |

An’ a heel behind. |

| |

Well, they didn’t know where; |

| |

That boy was gwine. [aka ‘going’] |

|

Ref: |

He Long John; etc. |

| |

|

| |

Well, in two or three minutes; |

| |

Let me catch my wind. |

| |

An; in two or three minutes; |

| |

I’m gone again. |

|

Ref: |

Oh! Long John; etc. |

| |

|

| |

Like a turkey through the corn; |

| |

Who’s [in] long corn. [aka ‘tall corn’] |

| |

Well, it’s John, John’; |

| |

Well, marble-eyed John. [aka ‘hard-eyed’] |

| |

Well-a, tenderfoot John; |

| |

With a long coat on: |

| |

Just a-skippin’ through the corn. |

|

Ref: |

Ah! Long John; etc. |

| |

|

| |

Well, you gonna tell; |

| |

What the Captain said. |

| |

Now, if you boys work; |

| |

Gonna treat pretty well. |

| |

Now, if you don’t work; |

| |

Gonna give you plenty hell. |

|

Ref: |

Now, long gone; etc. (28) |

But generally, blues singers adopted a far less

violent/extreme attitude.. Part of the African American culture

included mythical locations which they could escape to, where no

whites existed; both psychological and actual safe havens-or the

‘mythological sector’. Probably, the most well-known in the

Blues is a land of plenty –Diddy Wah-Diddy. This featured

endless wonders such as obliging ready-cooked chickens coming down

the road who already have forks sticking in them saying “Eat me! Eat

me!”, and endless lines of wagons filled with cotton, reaching right

round the base of a mountain to keep the money rolling in. Of

course the recording by Blind Blake (see JSP 7714 ) has transformed

this title into sexual symbolism-in itself a form of protest.

Another such ‘land of plenty’ probably came into

being after recorded blues had commenced, in 1920. This was a

form of ‘heaven’ yet to be constructed and appears in blues by both

men and women singers-albeit with differing emphasis. In 1930,

erstwhile farmer-cum-preacher, Son House chose the path of the Blues

and recorded one of the most raw-voiced sides in the Mississippi

Delta style. (see JSP 7715).

| |

Ohhh! I wished I had me a heaven of my own; |

|

(Spoken): |

Great God Almighty! |

| |

Yeahhhh! Heaven of my own. |

| |

Then I’d give all my women a long, long happy

home. (29) |

In 1934, at his last pre-war recording session,

in Texas, at Fort Worth, Texas, Alexander greatly extended this

theme; stamping his secular credentials in indelible ink.

| |

Take me out of this [river] bottom before the

high water rise. (x 2) |

| |

You know I ain’t no Christian, an’ I don’t wanna

be baptized |

| |

|

| |

I never been to Heaven, people but I’ve been

told; |

| |

Says, I never been to Heaven, people but I’ve

been told. |

| |

Oh! Lord. It’s women up there got they mouth

chock full of gold. |

| |

|

| |

I’m gonna build me a heaven, have a

kingdom of my own; |

| |

Gonna

build me a heaven, have a kingdom of my own. |

| |

So

these brownskin women can cluster around my throne. (30) |

In 1924, Bessie Smith put out the very fine

Work House Blues [Columbia 14032-D] which appears to be

introducing this ‘heaven’ verse. But her take differs markedly

from her male contemporaries, Son House and Texas Alexander.

[Other titles listed in B.&G.R. as ‘Wash

House’/’Work House Blues’ are different songs omitting the ‘heaven’

verse.]

| |

Say, I wish I had me a heaven of my own; |

| |

Say, I wish I had a heaven of my own. |

| |

I’d give all the poor girls, a long, old happy

home. (31) |

In the South these ‘poor girls’ would include

prostitutes and the highly-exploited black domestic servants which

makes up the 3rd. sector of early black protest in the

Blues. The latter found a major source of employment in

this occupation despite the long hours of endless drudgery, poor pay

and racial abuses, often from their white female bosses. Although

again often more implied there were rarer instances when a

singer would tell it like it is. The ubiquitous black washerwoman

was one who made some of her anger, despair, and disillusionment

more obvious. Bessie Smith, the ‘Empress of the Blues’, on

another title Washwoman’s Blues [Columbia 14375-D] is but one

example.

|

1. |

All day long I’m slavin’. All day

long I’m bustin’ suds. (x2) |

| |

Gee! My hands are tired washin’ out these dirty duds. |

| |

|

|

2. |

Lord, I do more work than a 40-11

Gold Dust Twin; [a washing machine] |

| |

Lord, I do more work than 40-11 Gold Dust Twin. |

| |

Done my self a-achin’ from my head down to my

chin. |

| |

|

|

3. |

Sorry, I do washin’, just to make my

livelihood. (x 2) |

| |

Oh! The wash woman’s life, it ain’t a

bit of good. |

| |

|

|

4. |

Rather be a scullion, cookin’ in

white folk’s yard. ( x 2) |

| |

I could eat a-plenty, wouldn’t have to work so hard. (32) |

Some wash women did this mind-destroying job in

their own place, while others had to take a heavy basket down to the

nearest muddy stream, using the humble washboard.

| |

Me an’

my washboard sure do have some cares an’ woes. (x 2) |

| |

In the muddy water, wringin’ out these dirty

clothes. (33) |

A couple of years earlier, in 1926, Edna Winston

painted a similar picture.

| |

Just scrubbin’ the steps in my coat; |

|

| |

For a livin’, boy, I cut my throat. |

|

Ref: |

Got a pail in my hand; |

| |

On my knees all day long. |

| |

|

| |

Ain’t got no chance to even be bad; |

| |

So full of ambition, sure makes me sad. |

| |

Lordy, Lord! What am I to do? (34) |

Ozie McPherson’s Down In The Bottom Where I

Stay [Paramount 12362] is a neat, if grim, summation of

the picture painted by these and other black female singers

in this early period of the Blues. Two years earlier, in

1924, Clara Smith had referred to her ‘highest aspiration’ in The

Basement Blues. [Columbia 14039-D]

| |

For I was born low-down, way down in the low

ground; |

| |

Every day I get low as a toad. |

| |

But my home ain’t here, it’s further down the

road. (35) |

The singer then breaks into some laid-back rap

with Ernest Elliott playing ‘dirty’ clarinet.

| |

There’s people in Mississippi where my folks are

at; |

| |

An’ colored folks don’t build much lower down

than that. |

| |

My papa’s name is Low. |

| |

Mr. Below, if you please. |

| |

An’ he can kiss my mammy without bending his

knees. |

| |

So, you keep your attic, take the roof or the air

if you choose; |

| |

Just keep your attic. Take the air if you choose. |

| |

But my highest aspiration is ‘The Basement

Blues’. (36) |

The sheer monotony of long hours of hard work

with minimal pay, even drove some poor women to contemplate suicide.

In these early days of the blues, this ‘solution’ to an unbearable

situation was much more common among white working classes than

blacks. In a rare blues, Helen Gross, proposes to ‘go out’ in

a spectacular and grisly fashion which probably influenced a later

recording by Leroy Carr (see JSP 77125) where he ‘did self-murder’.

| |

A

woman’s got to work so hard; |

| |

When

she’s in the white folk’s yard. |

| |

|

| |

Every

day it’s just the same; |

| |

Lordy! It’s a needless shame. |

| |

|

| |

I

still keep on workin’ til the day I die. (x 2) |

| |

All day long I hang my head an’ cry. |

| |

|

| |

Now,

the road is rocky, won’t be rocky long. (x 2) |

| |

Soon

there’ll be another gal gone wrong. |

| |

|

| |

Gonna take a pistol an’ blow out my brains. (x

2) |

| |

Then you’ll see the last of my remains. (37) |

|

However, generally singers were far more

positive and drew strength from the Blues which are, after

all, the basis of survival + quality. In 1925, Hociel

Thomas chose to sell illicit booze to supplement her meager

wages on

Wash Woman Blues [OKeh 8289]. Hattie Burleson on the

other hand, sought to move out of her cramped circumstances

and presumably get a similar servant’s job that also paid a

little more. Her

Sadie’s Servant Room Blues [Brunswick 7042] in 1928 is

quite a unique expression in the annals of the early blues.

|

1. |

Mrs. Jarvis don’t pay me much; |

| |

They give me just what they think I’m worth. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

I’m gonna change my mind; |

| |

Yes! Gonna change my mind |

| |

‘Cos I keep them ‘Servant—Room Blues’ all the

time. |

| |

|

|

2. |

I receive my company in the rear; |

| |

Still, these folks don’t want to see them here. |

|

Ref: |

Gonna change my mind; etc. |

|

| |

|

|

3. |

I’m gonna change this little room for

a nice big flat; |

| |

Gonna let my friends know where I’m

livin’ at. |

|

Ref: |

Gonna change my mind; etc. |

| |

|

|

4. |

They have a party at noon; |

| |

A party at night. |

| |

The midnight parties don’t ever break up right

[also noisy and go on to the wee wee

hours] |

|

Ref: |

Gonna change my mind; etc. (38) |

The anger that Wilmer Davis obviously feels in

her situation, graphically titled Gut Struggle [Vocalion

1034] spills over into her spoken comments during the break, where

she is supported by attacking banjo played by Johnny St. Cyr and

clarinet by Albert Nicholas who puts a sting in the tail.

|

Spoken: |

Put ‘em in the alley, boys, where I

belong. Play it, Mr. So-and-So. You don’t mean me no

good.

|

| |

Pass that liquor round, let’s all get drunk. See

if I care. Tell ‘em about Miss Wilmer Davis, Lord.

|

| |

|

|

1. |

When I get drunk who’s gonna take me

home? |

| |

Papa, when I get drunk I don’t know

right from wrong. |

| |

|

|

2. |

I’ve been in a struggle, folks, an’

it’s really true; |

| |

That’s why I’ve got those ‘Gut

Struggle Blues’. |

| |

|

|

3. |

I’ve struggled hard here an’ I’ve

struggled everywhere; |

| |

An’ I’ve got to take it for my share. (39) |

Her closing shouted comment in the break was

surely echoed by a great majority of African Americans in 1926, when

she recorded Gut Struggle.

|

Spoken:

|

Oh! Dowdy. Yes, I’m rowdy. Blow it

an’ you won’t know it. Play it, boys. You know I’m

feelin’ crazy about you. An’ I am, too. Oh! Mess around

with it , papa. I feel so unnecessary! (40) |

While Gene Campbell, from Texas, unusually aware

(for that time) at the debilitating repetitive drudgery endured by

black female domestic servants, offers his wife another alternative.

One to be taken only as a desperate last chance for survival.

| |

I’ve got somethin’ that stays on my mind. (

x 2) |

| |

A woman ain’t nothin’ but a fool when wash an’

iron all the time. |

| |

|

| |

I want

to tell all you women, I want you-all to know. (x 2) |

| |

What’s the use of washing an’ ironing when there’

a better way to go? |

| |

|

| |

I wouldn’t have a wash woman, I’ll

tell you the reason why. (x 2) |

| |

All the money she can make washing won’t buy me a

decent tie. |

| |

|

| |

I’m

sorry for you women, I know just how you feel. (x 2) |

| |

Before

I’d have a wash woman, I’d hi-jack, rob an’ steal. (41) |

A situation in which one that Sippie Wallace-also

from Texas-describes could be the only option.

| |

I want to get my washing off the line today; |

| |

What will become of me if I don’t get my pay?

(42) |

But

although some blues including those discussed above, referred to

‘struggling women’, surprisingly there were not as many recorded as

might have been expected. This may have been because most female

blues singers did not hire themselves out for domestic service.

As with their male But

although some blues including those discussed above, referred to

‘struggling women’, surprisingly there were not as many recorded as

might have been expected. This may have been because most female

blues singers did not hire themselves out for domestic service.

As with their male

contemporaries,

they eschewed the white, Protestant ‘work ethic’-at least the

most exploitative situations. Or a singer like Clara Smith

would last for only a very short period doing such work, to suit her

own requirements. As with Ms. Smith, leaving at the first

opportunity when the first traveling show eased into town. Of

course she was fortunate in being blessed with a powerful singing

voice which soon brought her national success. [See

current book on Clara Smith (WIP) by Max Haymes which hopefully will

be published sometime in 2016. Tentative title is ‘Got The Blues For

The Queen Of The Moaners’ (A tribute and appreciation of the life

and songs of Clara Smith)] contemporaries,

they eschewed the white, Protestant ‘work ethic’-at least the

most exploitative situations. Or a singer like Clara Smith

would last for only a very short period doing such work, to suit her

own requirements. As with Ms. Smith, leaving at the first

opportunity when the first traveling show eased into town. Of

course she was fortunate in being blessed with a powerful singing

voice which soon brought her national success. [See

current book on Clara Smith (WIP) by Max Haymes which hopefully will

be published sometime in 2016. Tentative title is ‘Got The Blues For

The Queen Of The Moaners’ (A tribute and appreciation of the life

and songs of Clara Smith)]

Although Clara, along with Bessie Smith (no

relation) Ida Cox, Ma Rainey Alberta Hunter, Edith Wilson and scores

of other singers who recorded in the 1920s, were the exception

rather than the rule. For many other less fortunate women, the

‘oldest profession’ was a preferred option to underpaid

drudgery, exploitation and abuse. The great Lucille Bogan, reported

to have been a sometime prostitute herself, as well as a bootlegger

and a gangster, describes in a classic song how even here, income

could dry up in the Great Depression. Her customers, or ‘tricks’,

seem to have all but disappeared.

| |

Sometimes I’m up, sometimes I’m down; |

| |

I can’t make my livin’ around this town. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

‘Cos tricks ain’t walkin’; |

| |

Tricks ain’t walkin’ no more. |

| |

I said, tricks ain’t walkin’; |

| |

Tricks ain’t walkin’ no more. |

| |

An’ I’ve got to make my livin’, don’t care where

I go. |

| |

|

| |

I need

shoes on my feet, clothes on my back. |

| |

Get

tired of walkin’ these streets all dressed in black. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

But tricks ain’t walkin’; etc. |

| |

|

| |

This way of livin’ sure is hard; |

| |

Duckin’ an’ dodgin’ the Cadillac Squad [aka the

police] |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

But tricks ain’t walkin’; etc. (43) |

Some five years later, ‘Little ‘ Alice Moore who

was based in St. Louis, Missouri, sang about the same problems as

the Depression ground on inexorably. A hard-hitting singer who is

accompanied here by fellow St. Louisan Peetie Wheatstraw -“High

Sheriff From Hell” on piano, she refers to prostitutes and herself

as a ‘daddy-calling mama’.

|

An’ I called me a daddy, just about half-past

nine. (x 2) |

|

|

An’ ‘e said “ No, no, lady. I ain’t got a dime. |

| |

|

An’ I called me another daddy, an’ he began to

fall. (x 2) |

|

He said “ Watch me make this old girl groan an’

havin’ three good balls.” [aka Pawn Shop sign] |

| |

|

If you is a daddy-callin’ woman, please take my

advice. (x 2) |

|

An’

stop callin’ sweet daddies, if you don’t feel they ain’t no dice.

[aka not a likely customer] |

| |

|

I used to stand on the corner, call every daddy

that came along. (x 2) |

|

But now that I have learnt better, I can sing

this ‘daddy-callin’’ song. (44) |

As well as protesting about wrongful arrest, the

convict lease system, etc. blues singers often told of being in a

prison cell for however long, and this was a familiar

situation for black citizens across the South and indeed in the more

‘liberated’ North. Even though the blues artist may not have

experienced serious incarceration-as opposed to overnight stays

after a drunken spree-they were fully aware that many of their

original working class black audience did and still do, in 2015.

(see classic example of ‘Mississippi Jailhouse Groan’ and a Rube

Lacy interview by David Evans. In my “Meaning In The Blues”

p.p.59-60. 4-CD set. JSP 77141D) An unshakeable solidarity

existed between the blues singer and blues listener, and this goes

back way into slavery days. Clara Smith sings and moans her

way through Waitin’ For The Evenin’ Mail [Columbia 13002-D].

Where she espies ‘a hard-luck brother moan’ standing at his narrow

cell window appealing to a long gone lover down in Jacksonville,

Florida, to send him bail. He says it’s a year ago

today and he is STILL ‘sitting on the inside looking on the outside”

while protesting his innocence and hoping fruitlessly for the dinero

to arrive on the evening mail train.

| |

Four

walls an’ a ceiling; |

| |

Lawdy! What a feeling. |

| |

Just a mean old low-down jail; |

| |

Separating me from everything but that evening

mail. (45) |

Blind Lemon Jefferson delivered a ‘holler-style’

Prison Cell Blues [Paramount 12622] in early 1928, where

after planting the blame for his sentence firmly on a woman called Nell;

he lays into the brutal prison staff from the ‘the captain’ on down.

| |

Got a red-eyed captain an’ a squabblin’

boss; |

| |

Got a mad-dog sergeant, an’ honey, an’ ‘e won’t

knock off. |

| |

I’m getting’ tired of sleepin’ in this lowdown

lonesome cell; |

| |

Lord, I wouldn’t be here if it had not been for

Nell. (46) |

Then he has a go at the ‘government’ and the

prison governor.

| |

I

asked the government to knock some days off my time; |

| |

But

the way I’m treated I’m ‘bout to lose my mind. |

| |

|

| |

I

wrote to the governor to please turn me a-loose; |

| |

Just

as I didn’t get no answer, I know it t’ain’t no use. (47) |

But irony and an unbeatable sense of humour also

feature in the Blues. The up-tempo rhythm by the rockin’ jazz outfit

which includes Charlie Green and Coleman Hawkins accompanying Bessie

Brown, belies the general ‘lot’ of the Southern black citizen in the

earlier 20th. century. Her line ‘Sing my song like

I’m happy an’ gay’ says it all.

| |

All my life I bin takin’ it; |

| |

All my life white folks takin’ it. |

| |

This old heart they just breakin’ it; |

| |

Ain’t gotta a thing to show what’ve I done done.

(48) |

Harking back to slavery times when the white boss insisted on the

slaves not to use a slow rhythm when picking cotton, as he realized

the speed of the song reflected the pace of their enforced work. So

they applied the lowdown words describing their feelings about the

whole horrendous system to a ‘jollier’ tempo. Another classic side

on this theme is the sarcastic On Our Turpentine Farm

[Columbia 14485-D] with deadly conditions in sub-tropical

temperatures as the black workers were often waist-deep in

malaria-infested swamp waters down in Georgia and North Carolina, as

well as other states, to collect the tar and turpentine from the

trunks of the longleaf pine, so essential to supplying naval stores

in the South. Singing to a lone guitar about ‘their’ turpentine farm

‘where the work ain’t hard an’ the weather is warm’.

Among the obviously tongue-in-cheek verses, appears one that strikes

closer to home as the ‘bossman’ (usually white) becomes a target.

| |

Our bossman is a lazy hound; |

| |

Chew ‘is tobacco, spits on the ground. |

| |

Smokes ‘is pipe an’ he lays in the shade; |

| |

Laziest man that ever was made. |

| |

On our turpentine farm (mm-mm) |

| |

On our turpentine farm. (mm-mm) |

| |

Where the work ain’t hard (mm-mm) |

| |

An’ the weather is warm. (49) |

The early blues singers moaned and directed their

anger and frustration at the whole unjust, moronic, and sometime

downright inhumane and insane Jim Crow system that prevailed

throughout their lives. As George Carter in his haunting

Rising River Blues [12750] states when addressing the

municipal authorities of the town he was in:

| |

I got

to move in the alley. I ain’t ‘llowed on your street. ( x2) |

| |

These

‘Rising River Blues’ sure have got me beat. (50) |

When he tries to flee the mounting high water of

yet another disastrous flood.

These singers employing symbolism, irony, and

anti-establishment lyrics which were often couched in an awful

beauty of obvious feeling-and yes, often with a black humour (no pun

intended). Not outright or in-your-face, You Got To Recognize Me

[OK 8330] from Charles Tyus is unique in early black

song. Tyus, the male partner of the vaudeville duo Charles &

Effie Tyus, making the black citizens’ case for equality with white

society. He praises early blues singers (in 1924) such as

Mamie Smith, Sara Martin and Virginia Liston, along with Mamie’s

cornet player Johnny Dunn. These are likened in their importance to

the scheme of things along with the ‘Underground Railroad’ hero,

ex-slave Harriet Tubman and influential political black leader

Booker T. Washington.

In a different setting but almost on a par with

the Charles Tyus song, is the totally anti-establishment offering by

Charley Campbell, who like Leadbelly also recorded for the L. of C.

It is still not entirely clear whether this is the same man who

recorded a couple of commercial sides for the Bluebird label in the

same year, of 1937. Campbell told Alan Lomax that this is a

“ain’t workin’ song”, pre-empting the later Trouble And Whiskey

[Decca 7862] by Roosevelt Sykes in 1941, where he sings:

| |

I’m gonna stop work, baby, an’ ramble from town

to town; |

| |

I’m gonna stop work, kind mama, an’ ramble from

town to town. |

| |

Because workin’ ain’t nothin’ but a habit, an’ I

believe I’ll lay it down. (51) |

And Martha Copeland sings her praises for

anti-hero Hobo Bill.

| |

Hobo Bill, he’s never got a dime; |

| |

He never goes to work ‘cos he’s never got the

time. |

| |

|

|

Ref: |

Ride on. Ride on, Hobo Bill. (52) |

While Alberta Hunter got lucky as she relates her

own experience, “an’ every word is true”, which she says could be

some help to her black listeners.

| |

I’ve been pushed an’ I’ve been driven, just drift

from door to door. (x 2) |

| |

But Dame Fortune have smiled on me, an’ I won’t

be pushed no more. (53) |

Because luck (and her talents) or ‘Dame Fortune’

led Alberta to a highly successful and lengthy career singing and

recording the Blues; bringing in much needed income.

Poverty was of course one of the major causes for

singing the Blues, linked with the great stumbling block of most

African Americans on the bottom of the socio-economic ladder—the

racialist regime run by whites known as ‘Jim Crow’. A rare detailed

reference to this odious system appears on the excellent North

Bound Blues [Columbia 14092-D] by Maggie Jones in 1925.

Some 18 months later, pianist Cow Cow Davenport was quite likely to

have been inspired to cut his boldly-titled Jim Crow Blues

[Paramount 12439]. This in turn might be a precursor of the

L.of C. recording by Leadbelly, made some 12 years later in 1938.

This being his Bourgeois Blues [issued on Rounder CD 1045].

The latter being adapted by the earlier folk circle in New York City

and the Civil Rights movement like, in the 1950s and 60s.

Nor did the Blues have it all its own way.

Parody of gospel songs thinly veiled social protest as in G.Burns

is Gonna Rise Again [OK 8577] which refers to resurrection as in

the religious line ‘these bones gonna rise again’. One very

well-known ‘protest song’ in the sacred mode was also picked up by

the Civil Rights and the folk singers: I Shall Not Be Moved

[Vocalion 1243] by Rev. Edward Clayborn in 1928. Also recorded

by other singers including Charley Patton. Preachers

themselves were often a hotbed of protest on behalf of the black

community, but very few appeared on disc. The

hard-hitting Hitler And Hell

[Bluebird B8851] by Rev. J.M Gates is exceptional. Recorded in

1941, his ‘mini-sermon’ –the WWII references aside- is so relevant

in war-torn countries across the globe here in the 21st.

century.

Protest not often very readily apparent but

protest just the same! As will be seen when trawling through the

remainder of this JSP set of essential blues and gospel recordings.

The Blues is survival music: with QUALITY!

From Lucille Bogan’s prostitute’s moan in They

Ain’t Walking No More, through laid-back irony on The Panic

Is On by Hezekiel Jenkins, via the international wartime protest

Hitler And Hell from the prolific Rev. J.M. Gates, to the

almost ‘throw-away’ spoken comment like ‘I feel so un-necessary’ by

Wilmer Davis and Charley Patton’s sung line ‘Every day seem like

murder here’ which says it all. They had the blues but they

sure were too damn mean to cry!

Max Haymes

October 2015.

|

Notes |

|

| |

|

|

1. ‘Down The Dirt Road Blues’ |

Charley Patton. |

|

2. Ibid. |

|

|

3. ‘He’s In The Jail House Now’ |

Memphis Jug Band. |

|

4. Ibid. |

|

|

5. Ibid. |

|

|

6. ‘Jail Bird Love Song’

|

Mississippi Sheiks.

|

|

7. Rediker M. |

p.19. ((‘The Slave Ship’) |

|

8. Ibid. |

|

|

9. Ibid.

|

p.20. |

|

10. Ibid. |

|

|

11. Lomax A. |

p.xv. (‘The Land Where The Blues Began’) |

|

12. Ibid. |

p.357. |

|

13. Charters S. |

p.30. (‘Country Blues’) |

|

14. Lomax |

Ibid. p.358. |

|

15. Evans David |

Notes to Female Blues Singers Vol.5 |

| |

[Document CD. DOCD-5509] 1996. |

|

16. ‘I’ve Got The Blues But I’m Just Too

Mean To Cry’ |

Dorothy Dodd.

|

|

17. ‘Railroad Bill’

|

Will Bennett.

|

|

18. ‘Mad Mama’s Blues’ |

Josie Miles. |

|

19. ‘Dynamite Blues’

|

Blind Lemon Jefferson.

|

|

20. Misiewicz Roger |

Notes to Bessie Tucker 19281929. |

| |

[Document DOCD-5070] CD. 1991. |

|

21. ‘Key To The Bushes Blues’ |

Bessie Tucker. |

|

22. Ibid. |

|

|

23. Ibid. |

|

|

24. ‘Red Ripe Tomatoes’ |

Jack Kelly. |

|

25. ‘Ain’t No More Cane On This

Brazos’ |

Ernest Williams |

|

26. Ibid. |

|

|

27. Lomax Alan |

Notes to The Library Of Congress Archive

Of Folk Culture. |

| |

[Rounder 1510] CD. 1998. |

|

28. ‘Long John’ (L of C ) |

Washington (‘Lightning’). |

|

29. ‘Preaching The Blues-Pt.1 |

Son House. |

|

30. ‘Justice Blues’

|

Texas Alexander.

|

|

31. ‘Work House Blues’

|

Bessie Smith.

|

|

32. ‘Washwoman Blues’

|

Bessie Smith.

|

|

33. Ibid. |

|

|

34. ‘Pail In My Hand’

|

Edna Winston.

|

|

35. ‘The Basement Blues’ |

Clara Smith. |

|

36. Ibid. |

|

|

37. ‘Workin’ Woman’s Blues’ |

Helen Gross. |

|

38. ‘Sadie’s Servant Room Blues’ |

Hattie Burleson. |

|

39. ‘Gut Struggle’

|

Wilmer Davis.

|

|

40. Ibid. |

|

|

41. ‘Wash And Iron Woman Blues’ |

Gene Campbell. |

|

42. ‘Sud-Bustin’ Blues’ |

Sippie Wallace. |

|

43. ‘They Ain’t Walking No More’ |

Lucille Bogan. |

|

44. ‘Daddy Calling Mama’ |

Alice Moore. |

|

45. ‘Waitin’ For That Evenin’ Mail’ |

Clara Smith. |

|

46. ‘Prison Cell Blues’

|

Blind Lemon Jefferson.

|

|

47. Ibid. |

|

|

48. ‘Song From A Cottonfield’ |

Bessie Brown. |

|

49. ‘On Our Turpentine Farm’

|

“Pigmeat Pete & Catjuice Charlie”.

|

|

50. ‘Rising River Blues’ |

George Carter. |

|

51. ‘Trouble And Whiskey’ |

Roosevelt Sykes. |

|

52. ‘Hobo Bill’ |

Martha Copeland. |

|

53. ‘Experience Blues’ |

Alberta Hunter. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Illustrations |

|

| |

|

|

1. Internet |

|

|

2. Yazoo CD [2006] 1992.. |

|

|

3. 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue. |

p.574. |

|

4. Author’s collection. |

|

|

5. Author’s collection. |

|

|

6. Rounder CD [1510] 1998. |

p.20. |

|

7. Document [DOCD-5523] 1997. |

Cover. |

|

8. Document [DOCD-5477] 1996. |

Cover. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Bibliography |

|

| |

|

|

1. Rediker Marcus |

The Slave Ship (A Human History) |

| |

[John

Murray. London] 2008. 1st. pub. 2007. |

|

2. Lomax Alan |

The Land Where The Blues Began |

| |

[Methuen. London] 1994. 1st. pub. 1993. |

Discography - CD 1

1.

Jailbird Love Song Mississippi Sheiks: Walter

Vinson

vo.gtr.yodelling; prob. Lonnie Chatman vln.; Bo

Chatman

vo.gtr.

Thursday, 12th.

June 1930. San Antonio, Texas.

(404145-B)

2. No

Job Blues Ramblin’ Thomas vo.gtr.,

speech.

c. February

1928. Chicago, Illinois.

(20343-2)

3.

Down To (sic) The Bottom Ozie McPherson vo. speech;

acc.Fletcher

Where I Stay Henderson’s Orchestra: Joe

Smith cor.; Charlie

Green tbn.;

Buster Bailey clt.; prob. Coleman

Hawkins bsx; Fletcher

Henderson pno.; Charlie Dixon bjo.

February 1926. Chicago,

Illinois.

(2422-4)

4. Gut

Struggle Wilmer Davis vo., speech;

Albert Nicholas clt.;

Richard M.

Jones pno.; Johnny St. Cyr bjo.

Saturday, 29th.

May 1926. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-375/*/7;

E-3184/85*/86W)

5.

Trouble And Whiskey Roosevelt Sykes vo.pno.; Sidney

Catlett dms.

Thursday, 21st.

February 1941. Chicago, Illinois.

(93519-A)

6.

Raise R-U-K-U-S Tonight Norfolk Jubilee Singers(as “Norfolk

Jazz

Quartet”):

J. ‘Buddie’ Archer ten. vo.; Otto

Tutson lead

vo.; Delrose Hollins bari. vo.; Len

Williams bs.

vo./manager; unacc.

April 1923.

New York City. New York.

(1370-2)

7.

Raise A Rukus Tonight Birmingham Jubilee Singers(as

“Birmingham

Quartet”):

Charles Bridges lead vo.; Leo ‘Lot’

Key ten.

vo.; Dave Ausbrooks bari. vo.; Ed

Sherrill bs.

vo.; unacc.

Thursday ,6th.

October 1927. New York City,

New York.

(144828-2)

8.

Landlady’s Footsteps Madlyn Davis vo.; unk. kaz.;

poss. Cassino

Simpson

pno.; unk.bjo.

c. September

1927. Chicago, Illinois.

(4802-2)

9. Get

On Board Clara Smith vo.; moaning; speech;

Porter

Grainger pno.;

Ethel Grainger, Odette Jackson

(as “Sisters

White & Wallace”) vo., speech,

shouts,

moaning.

Tuesday, 23rd

November 1926. New York City,

New York.

(143143-1)

10.

I’m Goin’ Home Charley Patton vo.gtr., speech.

Friday, 14th.

June 1929. Richmond, Indiana.

(15227--)

11.

Old Rattler (L of C) Mose ‘Clear Rock’ Platt & James

‘Iron Head’

Baker vo.;

unk. dog imitations; one or two unk.

convicts

vo.; unacc.

Prob. May

1934. Central State Farm, Sugar

Land, Texas.

(208-B-1)

12.

Ain’t No More Cane On Ernest Williams vo. prob. speech;

James ‘Iron

This/The Brazos (L of C) Head’ Baker & convict group moaning;

Alan

Lomax speech; unk. male

speech.

December 1933. Central State

Farm, Sugar

Land, Texas.

(199-A-1)

13.

The Prisoner’s Blues Sara Martin vo.; acc. Clarence

Williams Blue

Five: Unk.

cor.; unk. tbn.; poss. Otto Harwick or

Don Redman

alt.; Clarence Williams pno.; unk.

bjo.; poss.

Cyrus St. Clair bbs.

Thursday, 25th.

March 1926. New York City.

New York.

(74073-A)

14.

Penitentiary Bound Blues Rosa Henderson vo.; prob. Jake

Frazier tbn.;

Bob Fuller

clt.; Louis Hooper pno.

Thursday, 19th.

February 1925. New York City,

New York.

(E-382//3/4/W)

15.

Wash And Iron Woman Blues Gene Campbell vo.gtr.

c. May 1930.

Chicago, Illinois.

(C-5703-)

16.

I’ve Got The Blues But I’m Dorothy Dodd vo.; unk. tpt.; unk. tbn.;

unk. ten.

Just Too Mean To Cry sax.; c. October 1921. New York

City. New

York.

(no matrix

given)

17.

Rising River Blues George Carter vo.gtr.

c. February

1929. Chicago, Illinois.

(21153-2)

18.

Song From A Cotton Field Bessie Brown(as “Original Bessie

Brown”) vo.;

poss. Rex

Stewart or Bobby Stark tpt.; Charlie

Green tbn.;

Harvey Boone clt.; Coleman

Hawkins ten.

sax.; Fletcher Henderson or poss.

Porter

Grainger pno.; Clarence Holiday bjo.;

poss. Del

Thomas bbs.

c. 29th.

March 1929. New York City, New York.

(E29531-)

19.

They Ain’t Walking No More Lucille Bogan vo.; Charles Avery pno.

late March

1930. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-5349-)

20.

Long John (L of C) Washington(as “Lightnin’”) vo.

acc. unk.

convict

group, (prob. 2) vo., axe cutting.

December

1933. Darrington State Farm. Sandy

Point,

Texas.

(183-A-2)

21.

Another Man Done Gone Vera Hall vo. unacc.

(L of C) Thursday, 31st.

October 1940. Livingston,

Alabama.

(AFS

4049-A4)

22.

Black Evil Blues Alice Moore(Little Alice from

St. Louis) vo.,

speech; Ike

Rodgers tbn.; Henry Brown pno.

Saturday 18th.

August 1934. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-9317--,-A)

23.

Richmond Blues-TK.1 Julius Daniels vo.gtr.

Monday, 24th.

October 1927. Atlanta, Georgia.

(40348-1)

24.

Bessie’s Moan Bessie Tucker vo., moaning;

K.D.Johnson pno.

Wednesday 29th.

August 1928. Memphis,

Tennessee.

(45436-2)

25.

Rock Pile Blues Sylvester Weaver vo.gtr.;

Walter Beasley gtr.

Sunday, 27th.

November 1927. New York City,

New York.

(81877-B)

26.

Highway 51 Blues Curtis Jones vo. pno.; Willie Bee

James gtr.;

Washboard

Sam wbd.

Tuesday,25th.

January 1938. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-2081-1)

Discography - CD 2

1.

Down The Dirt Road Blues Charley Patton vo.gtr., speech.

Friday, 14th.

June 1929. Richmond, Indiana.

(15215--)

2.

Po’Mo’ner Got A Home At Fisk Jubilee Singers: John Work II 1st.

ten.vo.;

Last James Andrew Myers 2nd.

ten. vo.; Leon P.

O’Hara bari.

vo.; Noah Walker Ryder bs. vo.

unacc.

Friday, 10th.

February 1911. Camden, New

Jersey.

(9923-3)

3.

That White Mule Of Sin John Byrd(as “Rev. George Jones And

Congregation:”) John Byrd preaching, gtr.vo.;

Mae

Glover(as “Sister Jones”) vo. chanting,

moaning;

unk. female vo.; unk. male vo.,

speech.

Monday, 29th.

July 1929. Richmond, Indiana.

(15394--)

4.

You’ve Got To Recognise Me Charles Tyus chanting, vo., speech;

Effie Tyus pno.

c. 11th.

July 1924. New York City, New York.

(72666-A)

5. I’m

All Out And Down (L of C) Leadbelly vo.gtr., chanting, speech.

March 1935. Wilton Connecticut.

(144-A)

6.

Prison Cell Blues Blind Lemon Jefferson vo.gtr.

c. February

1928. Chicago, Illinois.

(20388-2)

7.

Moaning Blues Moanin’ Bernice Edwards vo.

moaning, pno.

c. February

1928. Chicago, Illinois.

(20371-1)

8. On

Our Turpentine Farm Pigmeat Pete & Catjuice Charlie: Wesley

Wilson vo.;

Harry McDaniels vo.gtr.

Monday, 7

October 1929. New York City, New

York.

(149105-3)

9.

Good Old Turnip Greens Bo Carter(as “Bo Chatman”) vo. prob.

vln.;

Charlie

McCoy mand.; prob. Walter Vinson gtr.

c. November

1928 New Orleans, Louisiana.

(NOR-756-)

10. Two

White Horses Standing In Smith Casey vo.gtr.

Line (L of

C) Dormitory, Clemens State Farm. Brazoria,

Texas.

(3552-A-1)

11. Jim

Crow Blues Cow Cow Davenport vo.pno.; B.T.

Wingfield cor.

c. January

1927. Chicago, Illinois.

(4085-3)

12. Am

I Right Or Wrong (L of C) Son House vo.gtr.

Friday, 17th.

July 1942. Robinsonville,

Mississippi.

(6607-B-2)

13. It

Makes A Long Time Man Kelly Pace vo.; unk. group of convicts vo.

unacc.

Feel Bad (L of C) c.

5th. October 1934. Camp No.5. Cumins State

Farm. Gould,

Arkansas.

(248-B-1)

14.

Waitin’ For The Evenin’ Mail Clara Smith vo., moaning; Fletcher

Henderson pno.

Monday, 1st.

October 1923. New York City,

New York.

(81250-2)

15. I

Shall Not Be Moved Rev. Edward Clayborn vo,gtr.

Saturday, 21st.

January 1928. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-1627/28*,E-7055/56*W)

16.

Toadfrog Blues Ma Rainey vo. acc. her Georgia

Jazz Band:

Howard Scott

cor.; Charlie Green tbn.; Don

Redman clt.;

Fletcher Henderson pno.; Charlie

Dixon bjo.;

unk. perc. effects.

c. 15th.

October 1924. New York City, New

York

(1923-2-)

17.

Squinch Owl Moan Too Tight Henry vo. prob. gtr.,

falsetto ‘owl’

imitations;

unk. gtr.; prob. Jed Davenport hca.

c. 2nd.

October 1930. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-6416-)

18.

Daddy-Calling Mama Alice Moore vo.; Peetie Wheatstraw

pno.

Wednesday,

17th. July 1935. Chicago, Illinois.

(90178-A)

19.

Mean Old World Heavenly Gospel Singers:

Roosevelt Fenoy lead

vo.; Fred

Whitmore ten. vo.; Henderson Massey

bari. vo.;

Jimmy Bryant bs. vo. unacc.

Wednesday, 7th.

August 1935. Atlanta, Georgia.

20. Cow

Cow Blues Dora Carr vo.; Cow Cow Davenport pno.

Thursday, 1st.

October 1925. New York City,

New York.

(73667-A)

21.

Last Fair Deal Gone Down Robert Johnson vo.gtr.

Friday, 27th.

November 1936. San Antonio,

Texas.

(SA-2631-1)

22.

Chain Gang Bound Bumble Bee Slim vo.; poss. own

gtr. or unk. gtr.

c. October

1931. Grafton, Wisconsin.

(L-1122-2)

23.

These Hard Times Are Tight Rev. J.M. Gates preaching, speech;

Sister Jordan

Like That speech; Sister Norman

speech; Deacon Leon

Davis

speech; unacc.

Friday, 12th.

December 1930. Atlanta , Georgia.

(404685-B)

24. The

Panic Is On Hezekiah Jenkins vo. prob. gtr.

Friday, 16th.

January 1931. New York City, New

York.

(151219-2)

25.

Preachin’ The Blues-Pt.1 Son House vo.gtr. speech.

Wednesday,

28th. May 1930. Grafton Wisconsin.

(L-410-1)

Discography - CD 3

1.

Starvation Farm Blues Bob Campbell vo.gtr.

Wednesday, 1st.

August 1934. New York City,

New York.

(15503-2)

2. No

Place To Go Walter Davis vo. pno.

Friday, 12th.

July 1940. Chicago, Illinois.

(049315-1)

3. One

Dime Blues Blind Lemon Jefferson vo.gtr.

c. October

1927. Chicago, Illinois.

(20075-2)

4.

Blue Harvest Blues Mississippi John Hurt vo.gtr.

Friday, 28th.

December 1928.

(40187-A)

5.

Fool’s Blues Funny Paper(as “Funny

Paper Smith”—The

Howling

Wolf) vo.gtr.

Friday, 10

July 1931. Chicago, Illinois.

(VO-167-A)

6. Boll

Weevil Blues (The Boll Vera Hall vo. unacc.

Weevil Holler) (L of C) Thursday

31st. October 1940. Livingston

Alabama.

(4049-B-3)

7.

Mississippi Bo Weavil Blues Charley Patton vo.gtr, speech.

Friday, 14th.

June 1929. Richmond, Indiana.

(15211--)

8.

Hopali(Hop-A-Lee) (L of C) 8 unknown girls vo. unacc.

c. October

1934. Kirby Industrial School,

Atmore, Alabama.

(88-B-3)

9.

Experience Blues Alberta Hunter vo.; acc. Her

Paramount Boys:

Tommy

Ladnier cor.; Jimmy O’Bryant clt.;

prob. Lovie

Austin pno.

October

1923. Chicago, Illinois.

(1528-1)

10.

Broken Levee Blues Lonnie Johnson vo.gtr.

Tuesday, 13th.

March 1928. San Antonio, Texas.

(400492-A)

11.

Eighteen Hundred And Ninety Charley Campbell

chanting, speech; unk. dock

One(Ain’t Working Song) workers

laughing, shouts; Alan Lomax speech.

(Lof

C) Wednesday, 28th.

July 1937. Mobile, Alabama.

(1336-B-2)

12.

Bank Failure Blues Martha Copeland vo.; Porter

Grainger pno.

Friday, 6th.

January 1928. New York City, New

York.

(14578-1)

13.

Hammer Ring (L of C) Jess Bradley vo.; unk. convict group

vo., shouts;

with 10 lb

two-headed hammers around 2 inches

diameter-spike driving railroad ties. unk. male

speech.*

Wednesday,

21st. November 1934. State

Penitentiary, Huntsville, Texas.

(219-A-2)

14. The

Escaped Convict George ‘Bullet’ Williams speech,

screams

through hca.

c. May 1928.

Chicago, Illinois.

(20593-2)

15. I’m

Having So Much Trouble Bumble Bee Slim vo. speech; prob. Albert

Ammons pno.

unk.gtr.

Wednesday,

27th. January, 1937. Chicago,

Illinois.

(C-17778-1)

16.

Worried Blues (L of C) Tom Bell vo.gtr.

Saturday, 3rd.

November 1940. Livingston,

Alabama.

(4067-A-1)**

17.

Workhouse Blues Leroy Carr vo. pno.; Scrapper

Blackwell gtr.

Thursday, 2nd.

January 1930. Chicago, Illinois.

(C-5076-)

18. The

Sure Route Excursion To Rev. F.W. McGee preaching; mixed group of

4

Hell-Pt.1 or 5

‘congregation’ shouted responses, moaning;

unacc.

Wednesday,

16th. July 1930. New York City,

New York.

(62354-2)

19.

Black Hearse Blues Sara Martin vo.; Sylvester

Weaver gtr.

Tuesday, 30th.

August 1927. New York City,

New York.

(81294-B)

20.

Washwoman’s Blues Bessie Smith vo.; Bob Fuller alto

sax.; Ernest

Elliott ten.

sax./clt.; Porter Grainger pno.

Friday 24th.

August 1928. New York City, New

York.

(146893-2)

21. Sud

Bustin’ Blues Sippie Wallace vo.; acc. Clarence

Williams’

Harmonizers:

Tom Morris cor.; Charlie Irvis

tbn.; poss.

Ernest Elliott clt.; Clarence Williams

pno.; Buddy

Christian bjo.

c. 6th.

June 1924. New York City, New York.

(72606-B)

22.

Hitler And Hell Rev. J.M. Gates preaching,

vo.; unk female &

unk. male chanting, speech, shouts, vo.; unacc.

Thursday, 2nd. October 1941. Kimball Hotel,

Atlanta, Georgia.

(071084-1)

23.

Don’t Mess With Me Mamie Smith vo.; acc. her Jazz

Hounds: prob.

Bubber Miley

tpt.; unk. tbn.; poss. Ernest Elliott

or Garvin

Bushell clt/alto sax.; Herschel

Brassfield

alto sax.; Coleman Hawkins ten. sax.;

unk. pno.

c. 6th.

December 1922. New York City, New

York.

(71080-B)

24. My

Daddy’s Calling Me Irene Scruggs vo.;Clarence Williams pno.

c. 1st.

May 1924. New York City, New York.

(72498-B)

25. I

Heard The Voice Of A Jim Jackson vo.gtr., speech.

Pork Chop Monday, 30th.

January 1928. Memphis

Auditorium.

Memphis, Tennessee.

(418021-1)

26. G.

Burns Is Gonna Rise Again Johnson-Nelson-Porkchop

Saturday,

17th. February 1928. Memphis,

Tennessee.

(400259-A,-B)

27. The

Bourgeois Blues (L of C) Leadbelly vo.gtr., speech.; unk. white

male

speech.

Monday, 26th.

December 1938. Havers Studio,

New York

City, New York.

(2502-B-2)

* see

Rounder CD 1517. in 1999, for more details of the spike drivers’

hammering method.

**Listed

on CD 1517 as ‘Worried Blues’ but appears in B.&GR as ‘I’m Worried Now

But I Won’t Worried Long’. Tom Bell actually sings ‘I’m worried now

an’ I won’t be worried long.’

Discography - CD 4

1.

Hobo Bill Martha Copeland vo.;

Porter Grainger pno.;

Buddy

Christian bjo.; unk. vo. train effects.

Tuesday, 9th.

August, 1927. New York City,

New York.

(144538-2)

2.

Dyin’ Crap-Shooter’s Blues Martha Copeland vo.; Ernest Elliott,

Bob Fuller

clt.; Porter

Grainger pno.

Thursday, 5th.

May. New York City, New York.

(144097-3)

3.

Dying Crap Shooter’s Blues*** Blind Willie McTell vo.gtr., speech.

(Lof

C) Tuesday, 5th.

November 1940. Atlanta, Georgia.

(4070-B-1)

4.

Sarah Jane Jazz Gillum vo. hca.; Big Bill

Broonzy gtr.

speech; unk.

bs.

Sunday, 5th.

April 1936. Chicago, Illinois.

(100311-1)

5.

North Bound Blues Maggie Jones vo.; Charlie Green

tbn.; Fletcher

Henderson

pno.

Thursday, 16th.

April 1925. New York City,

New York.

(140534-2)

6. Go

Down Old Hannah (L of C) James ‘Iron Head’ Baker

vo.; Will Crosby, R.D.

Allen, Mose

‘Clear Rock’ Platt vo. unacc.

Prob.

December 1933. Central State Farm.

Sugar Land,

Texas.

(195-A-2)

7. I

Been Drinkin’ (Lof C) Vera Hall vo. unacc.

Friday, 23rd.

July 1937. Livingston, Alabama.

(1323-B-3)

8. Po’

Laz’us (L of C) Vera Hall vo. unacc.

Thursday, 31st.

October 1940. Livingston,

Alabama.

(4050-A-1)

9.

Cotton Seed Blues Tampa Red vo.gtr.; Georgia Tom

pno.

Tuesday, 10th.

February 1931. Chicago, Illinois.

(VO-121-A)

10. I

Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray Paramount Jubilee Singers: mixed vo.

group;

unk.

conductor; unacc.

mid-November

1923. New York City, New

York.

(1570-2)

11.

He’s In The Jailhouse Now Memphis Jug Band: Charlie Nickerson

vo.; Will

Shade hca.;

Vol Stevens bjo.-mand.; Charlie

Burse gtr.,

poss. harmony vo.; Jab Jones jug.

Friday, 21st.

November 1930. Memphis,

Tennessee.

(62990-2)

12.

Railroad Bill Will Bennett vo.prob.gtr.

Wednesday,

28th. August 1929. WNOX Studios.

St. James Hotel. Knoxville, Tennessee. (K-127-)

13. Mad

Mama’s Blues Josie Miles vo.; acc. Kansas City

Five: prob.

Bubber Miley

cor.; prob. Jake Frazier tbn.; prob.

Bob Fuller

clt.; unk. pno.; prob. Elmer Snowden

bjo.

Friday, 21st.

November 1924. New York City,

New York.

(9862-)

14.

Dynamite Blues Blind Lemon Jefferson vo.gtr.

c. January

1929. Chicago, Illinois.

(21096-1)

15. Key

To The Bushes Blues Bessie Tucker vo.; K.D. Johnson pno.

Jesse

Thomas gtr.

Thursday, 17th.

October 1929. Dallas, Texas.

(56404-2)

16. Red

Ripe Tomatoes Jack Kelly vo.gtr. acc. His South

Memphis Jug

Band: prob.

Dan Sane gtr.; Will Batts vln.; D.M.

“Doctor”

Higgs jug.

Tuesday,1st.

August 1933. New York City, New

York.

(13714-2)

17.

Justice Blues Texas Alexander vo.; poss.

Willie Reed gtr.;

unk. gtr.

Saturday, 29th.

September 1934. Fort Worth,

Texas.

(FW-1130-1)

18.

Nobody Knows The Way I Clara Smith vo.; Louis Armstrong cor.;

Charlie

Feel Dis Mornin’

Green tbn.; Fletcher Henderson pno.

Wednesday, 7th.

January 1925. New York City,

New York.

(140226-1)

19.

Pail In My Hand Edna Winston vo.; TomMorris

cor.; Charlie

Irvis tbn.;

Bob Fuller clt.; Mike Jackson pno.;

Buddy

Christian bjo.

New York

City, New York.

(36960-3)

20. The

Basement Blues Clara Smith vo.; Ernest Elliott clt.;

Charles A.

Matson pno.

Saturday, 20th.

September 1924. New York City,

New York.

(140052-1)

21.

Workin’ Woman’s Blues Helen Gross vo. acc. Choo Choo

Jazzers: Rex

Stewart

cor.; Bob Fuller clt.; Louis Hooper pno.

c. December

1924. New York City, New York.

(31759)

22.

Broke Man Blues Sylvester Palmer vo.pno.,

moaning.

Friday, 15th.

November 1929. Chicago, Illinois.

(403305-B)

23.

Sadie’s Servant Room Blues Hattie Burleson vo.; Don Albert tpt.;

Siki

Collins sop.

sax.; Allen Vann pno.; John Henry

Bragg bjo.;

Charlie Dixon bbs.

c. October

1928. Dallas, Texas.

(DAL-745-A)

24. Red

Cross Man Lucille Bogan(as “Bessie Jackson”)

vo.; Walter

Roland pno.

Monday, 17th.

July 1933. New York City, New

York.

(13548-1)

25.

Life is Just A Book Washboard Sam vo.wbd.; Memphis

Slim pno.;

Big Bill

Broonzy gtr.; William Mitchell im. bs.

Thursday, 26th.

June 1941. Chicago, Illinois.

(064477-1)

***see

10,000 word dissertation by Max Haymes (1992) tracing the roots of

McTell’s ‘Dying Crapshooter’s Blues’ back to mid-18th.