Dark was the

night and cold was the ground on which Blind Willie Johnson was laid.

Yet after his death, his music would streak to the stars on the Voyager

and become part of the “music of the spheres.”

| |

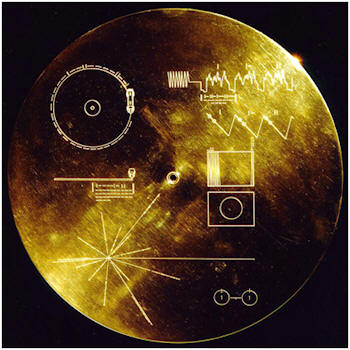

The Voyager Golden Record was sent into space in 1977, carrying

greetings in 60 languages, sounds of nature and the music of

Beethoven, Bach and Blind Willie Johnson. Carl Sagan likened it to

throwing a bottle into the cosmic ocean.

|

|

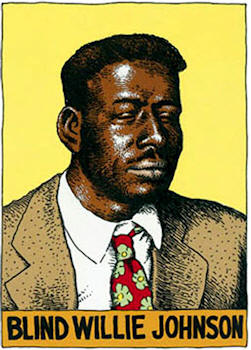

This

beautiful portrait of Blind Willie Johnson by renowned artist R.

Crumb was published in "R. Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz & Country,"

along with dozens of other iconic portraits. Crumb’s portraits of

blues musicians also appear on “Heroes of the Blues” T-shirts.

|

“Looked

around all day for a job, and I looked almost every place.

It’s

hard to come home and find hunger on your children’s face.”

— Juke

Boy Bonner

Those

heartrending words are not merely song lyrics. They are the

real-life testimony of a bluesman — the single father of three young

children — who is singing his sorrow about what it feels like to

come home from a fruitless search for work and see hunger and

deprivation on the faces of the children he loves above all else.

The

verses composed by Weldon “Juke Boy” Bonner, a gifted poet and blues

musician who grew up as a sharecropper in Texas and lived in poverty

in Houston for most of his adult life, provide an important clue

into the mystery of why so many blues artists sing with such passion

about poverty, injustice and homelessness.

Many of

the finest blues musicians in history grew up in poverty — and some

of them died still poor. Especially in the first few decades of the

blues, many great artists made very little money despite their

prodigious talent, and were forced to take menial jobs to make ends

meet. Yet, that sometimes gave them the insight to create highly

meaningful songs about lives broken down by economic hardships,

hunger, evictions, and despair.

We can

get a glimpse into this hidden dimension of the blues by taking a

closer look at the lives and music of two brilliant Texas musicians:

Weldon “Juke Boy” Bonner and Blind Willie Johnson.

The Ghetto Poet

Although

almost forgotten today even in blues circles, Juke Boy Bonner was a

remarkable poet and a gifted blues guitarist and singer. He

sometimes performed as a one-man band, singing his poetic songs

while accompanying himself on guitar, harmonica and percussion.

Some of

Bonner’s lyrics are poetry in the true sense. Even when he is near

despair, his songs are beautiful and uplifting in the way they speak

to the human condition. His song, “It Don’t Take Too Much,” offers a

melancholy account of a beautiful loser, a man with a heart full of

soul, crushed by the weight of the world.

“It

don’t take too much to make you think you were born to lose.

You got

to keep on pushing at that mountain, and it never seems to move.”

The two

sides of Bonner’s identity as an artist are expressed by the titles

of two of his finest records, produced by Chris Strachwitz on

Arhoolie. His dark-blue, despairing side is captured by “Life Gave

Me a Dirty Deal,” and his identity as a poet from the poor side of

town is expressed as “Juke Boy Bonner — Ghetto Poet.”

In “It

Don’t Take Too Much,” Bonner reveals how the blues can strike on an

economic level — when you can’t find a job — and simultaneously

strike at an emotional level — when your wife leaves you. The

inequities of a world that’s “doing you wrong” cause the downcast

blues by breaking up your home.

“It

don’t take too much to make you feel the world is doing you wrong,

Especially when you can’t find no job,

You

can’t take care of your wife and your home.”

This

poet laureate of the blues, as Brett Bonner (no relation) of

Living Blues magazine once described Juke Boy, was also one of

the strongest political voices in the blues, speaking out against

the economic inequality of U.S. society.

In

describing his own tough existence in Houston’s poor neighborhoods,

this lone bluesman also became the voice for countless poor people

who have found that the “upper-class people” don’t give a single,

solitary damn about the survival of the poor.

“It

don’t take too much after you gave all that you can give.

Look

like upper-class people don’t care how the lower class of people

live.”

In

Living Blues magazine, Brett Bonner described Juke Boy Bonner as

one of the most important poets in the blues.

He

wrote, “If you had to choose a poet laureate of the late ‘60s/early

‘70s blues scene, you would be hard pressed to find someone more

qualified than Juke Boy Bonner. Bonner’s songs speak beautifully and

forcefully of the struggle of African Americans. While many blues

songwriters focus attention on themselves and their place in the

world, Bonner’s songs display a social consciousness that stretched

far beyond himself.”

After

Bonner’s marriage at a young age resulted in three children, his

wife unexpectedly left him, leaving him solely responsible for his

children’s upbringing, a burden made heavier by his own poor health

and economic struggles.

In the

liner notes to Bonner’s album, “Life Gave Me a Dirty Deal,” Chris

Strachwitz, founder of Arhoolie Records, explained how the burden

was also a blessing. “Perhaps the most unhappy period in Weldon

Bonner’s life was his marriage. His wife left him after giving him

what he considers the greatest gift in his life, his three

children…. Weldon lavished attention, education, responsibilities,

and affection on his family. They are all wonderful, lively,

intelligent young people.”

Yet his

years as a single parent were also full of hardships. Even though

Bonner was a genuine poet and a gifted musician, he often was unable

to support his family with his music at low-paying blues venues.

In “What

Will I Tell the Children,” he sings the hard-working, low-paying,

single-parent blues, returning home feeling empty inside after

failing to find a job.

“You

know it’s so hard when you’re trying to make it,

you’re

living from day to day.

You go

down and apply for a job and the people turn you away.

What

shall I tell my children, oh Lord, when I get home? Tell them,

‘Maybe

tomorrow, maybe tomorrow all our troubles will be gone.’”

He sings

the words “maybe tomorrow” so forlornly, as if he’s grasping at a

slender thread of hope. What if tomorrow doesn’t deliver on those

hopes?

In

another song on “Ghetto Poet,” Bonner sings, “All the lonely days

just seem to fade away.” Then the days turn into endless years of

broken dreams: “All the lonely years just seem to disappear.”

As we

will see, Bonner was not only enduring economic deprivation,

loneliness, the pressures of single fatherhood, and disillusionment

that his brilliant music never seemed to find a large audience, but

was also enduring scary health issues.

Yet when

a sensitive poet undergoes that level of suffering, even his

despairing words can still be striking and memorable, as in his

song, “It’s Enough.”

“Look

like I’m waiting for a tomorrow that will never come,

Seems

days and days have passed, yet I never see the sun.

It’s

enough to make you wish you were never born.

Sometimes I wonder where I get the power and the strength to carry

on.”

|

“I’m a Bluesman”

“My father passed on when I was two years old,

Didn’t leave me a thing but a whole lot of soul.

You can see I’m a bluesman.”

Those lonely and forsaken lines are from Bonner’s

self-revealing song, “I’m a Bluesman.” Being a bluesman was

at the very heart of his identity, and this song reveals the

major events of his life as reflected in the mirror of the

blues.

Weldon Bonner was born on a farm near Bellville, Texas,

where his father, Manuel Bonner, was a sharecropper. His

very first years seemed to foreshadow all the bad luck that

stalked him all his life. He was born in 1932 just as the

rural economy was collapsing during the Depression. |

|

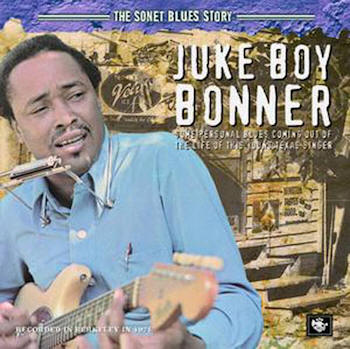

Juke Boy Bonner's

song, "I'm a Bluesman," can be found on this CD, "The Sonet

Blues Story: Juke Boy Boonner." |

He was

the youngest of nine children born into a poor family, and just as

he sang in “I’m a Bluesman,” his father died when he was only two.

Then, Bonner’s mother died when he was only eight.

“My

mother passed on when I was just about eight,

I

started learning I was growing up in a world of hate.

That

made me a bluesman.”

In his

1975 book, The Legacy of the Blues, the pioneering blues

author and record producer Samuel Charters described the one-on-one

correlation between Juke Boy Bonner’s life and his autobiographical

song, “I’m a Bluesman.”

After

losing both parents, Bonner went to live with an older sister in

Bellville. Instead of going to school, he was working in the Texas

cotton fields when he was only 13, just as he sang so movingly.

“I go to

work in the fields when I was just thirteen.

Didn’t

get a chance to know what education means.”

In 1963,

at the age of 30, Bonner was hospitalized for chronic ulcers and 45

percent of his stomach was removed. During his long recovery, he

began writing poetry and had countless poems published in Forward

Times, the African-American newspaper of Houston.

Bonner

turned many of these poems into beautiful songs and became a fine

singer, guitarist, and harmonica player. His music was championed,

first by Mike Leadbitter, a leading blues researcher and writer for

Blues Unlimited in England, and later by Chris Strachwitz,

the founder of Arhoolie Records in El Cerrito, who released his

finest records.

Yet for

all the brilliance of his artistry, Juke Boy Bonner would never

become a star.

At the

end of “I’m a Bluesman,” Bonner sings the desolate and downhearted

words that, in my mind, make him one of the most important and

prophetic voices of the homeless condition in America. All the hard

knocks he endured gave him the knowledge and sensitivity to capture

the frightening insecurity of life on the streets.

“When at

night you don’t know where you’re going to sleep,

or where

you’ll get your next meal to eat

That

makes you a bluesman, a bluesman.

I want

the world to know how come I’m a bluesman.”

In “I’m

in the Big City,” Bonner writes of his disillusionment in moving

from the hard, bare existence of a sharecropper’s life on a Texas

cotton farm to Houston, only to find that poverty had followed him

to the big city. “Here I am in the big city and I’m just about to

starve to death.”

“I’m a

Bluesman” appeared on “The Sonet Blues Story: Juke Boy Bonner,” and

his other songs appeared on “Life Gave Me a Dirty Deal” and “Ghetto

Poet.” Strachwitz produced all these intensely moving records by a

talented musician and poet, and Charter was the creative force

behind the Sonet Blues series.

Without

his work being championed by Chris Strachwitz, Samuel Charter and

Mike Leadbitter, Juke Boy Bonner might have lived and died almost

completely unknown.

A

Hero of the Blues

Although

Bonner never became a big star, he was a voice of his people, a

wonderful poet and a courageous bluesman who kept playing even after

half of his stomach was removed.

He gave

concerts and performed at blues festivals all over the country and

traveled to Europe with the American Folk Blues Festival. But

somehow, he never had a breakthrough moment in his career.

The

life-stories of great artists in America are supposed to follow a

rags-to-riches story arc. When a sensitive young man is born into an

impoverished family of sharecroppers on a Texas farm just as the

Depression ruins the economy, and then loses both parents, we are

primed to expect that his years of hard work and brilliant artistry

will be rewarded someday.

Yet, if

the first chapters of Bonner’s life were harsh and cruel, the last

chapter was outright heartbreaking.

Even

though he had written and published hundreds of poems, and had

recorded blues albums of unquestionable worth and beauty, in

Bonner’s last years he held down “a dreadful minimum wage job” in

Houston, as Strachwitz explained in the notes to “Life Gave Me a

Dirty Deal.”

“The

last time I visited Juke Boy in Houston,” Strachwitz wrote, “he was

working at a chicken processing plant, depressing work for anyone

but especially demoralizing for a sensitive poet like Weldon

Bonner.” Strachwitz later wrote that he would never forget the bad

shape Juke Boy was in while working that job.

Then,

when he was only 46 years old, Bonner died on June 28, 1978, in “the

small rented room where he lived” in Houston. The last verses of

Bonner’s overpowering song, “It Don’t Take Too Much” express the

essential truth of this poet’s lifelong struggle with the blues.

“It

don’t take too much to make you think you was born to lose

That’s why I lay down worrying and I wake up with the blues.”

Despite

his lack of public recognition, Juke Boy Bonner lived and died a

great poet — and a hero of the blues. As I write these words, I

realize I am wearing a T-shirt with an iconic portrait of Blind

Willie Johnson by the artist R. Crumb and the blazing inscription:

“Heroes of the Blues.”

For one

forlorn moment, I find myself wishing that Juke Boy Bonner had also

been consecrated as a hero of the blues, and that during his

lifetime he had enjoyed some of the success lavished on so many

lesser musicians.

From

past experience, I know where these wishes will soon lead. I’ll

begin wishing for a world where the genuine blues artists like Juke

Boy Bonner and Blind Willie Johnson are far more celebrated than the

Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin and all the others who have grown

rich while exploiting the blues. As long as I’m wishing for the

impossible, why not wish for eyesight for the blind? In fact, why

not wish for eyesight for Blind Willie Johnson?

Even

though justice is too often delayed, it may still show up on some

unexpected day. After all, one of the greatest musicians in our

nation’s history, Blind Willie Johnson, spent the last 17 years of

his life in nearly total obscurity, playing his breathtaking music

for strangers on small-town street corners, and then died a lonely

death. Yet now, his music sails among the stars.

Blind Willie Johnson and the Music of the Spheres

In the

opening frames of “The Soul of a Man,” a film by director Wim

Wenders in the film series “Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues,”

NASA technicians are seen loading a golden record on board the

Voyager as it is about to blast off to explore the outer reaches of

our solar system and then continue on into deep space.

The

Voyager Golden Record carried the “Sounds of Earth” — the diverse

languages, music and natural sounds of surf, thunder, birds and

whales. Carl Sagan likened it to launching a message in a bottle

into the “cosmic ocean.” The Voyager Golden Record selected the

music of Bach, Beethoven and Blind Willie Johnson to carry on this

voyage into the solar system, past Pluto and to the stars beyond.

It is

amazing to contemplate this starry destiny for Blind Willie’s music,

since during his life he seemed the most earthbound of men. He was

born into poverty in Texas, blinded as a very young child, and later

died in obscurity.

Johnson

lost his mother at an early age. He would later sing a deeply moving

rendition of “Motherless children have a hard time when the mother

is gone.” During his youth, Willie Johnson walked down many lonely

roads in darkness. He would die in much the same way, after sleeping

on a soaked mattress when his house burned down.

Yet

Johnson is now immortalized as one of the most brilliant slide

guitarists in the history of gospel and blues music, and his

haunting rendition of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” is

now soaring into space. His music truly has become part of the

“music of the spheres.”

Many

musicians win gold records for reaching one million dollars in sales

(or by later standards, 500,000 units). Blind Willie Johnson’s music

is on the ultimate gold record, shining among the stars.

Johnson

was a stunning original. Samuel Charters wrote that no one during

his time sounded like Blind Willie Johnson as a singer or guitarist.

But Johnson would soon influence everyone else. Musicians to this

day are still devoting years of their lives in an attempt to figure

out his incredibly beautiful and complex slide guitar playing.

In the

liner notes to “The Complete Blind Willie Johnson” on Columbia,

Charters wrote: “He was one of the most brilliant slide guitarists

who ever recorded, and he used the upper strings for haunting

melodic phrases that finished the lines he was singing in the text.”

Sandblasted Vocal Cords

Blind

Willie Johnson didn’t sing the blues, however. Every song he

recorded between the years of 1927 to 1930 was a gospel song, yet

his slide guitar playing sounded like the very essence of the blues,

and he sang loud enough to wake the dead in a rasping growl that

sounded like his vocal cords had been sandblasted.

His

beautifully expressive, yet deep and raw vocals remade gospel music

so it sounded like the primal blues of the Mississippi Delta, as if

the harsh, gravel-voiced singing of Son House had mingled with the

intense, passionate vocals of Howlin’ Wolf. Yet Blind Willie Johnson

grew up in rural Texas, not Mississippi, and his music preceded most

of the blues artists. Where did it come from?

Many of

the finest guitarists in the world are in awe of Blind Willie

Johnson. Some have spent half their lives trying to replicate what

he could do on a slide guitar. How did a blind young man who played

in small towns in an isolated area of rural Texas become one of the

most masterful guitarists of all?

Ry

Cooder, a virtuoso slide guitarist himself, described what Blind

Willie Johnson’s playing meant to him. “Of course, I’ve tried all my

life — worked very hard and every day of my life, practically — to

play in that style. He’s so good. I mean, he’s just so good! Beyond

a guitar player. I think the guy is one of these interplanetary

world musicians.”

He’s

exactly right about the “interplanetary” part. Blind Willie

Johnson’s performance of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,”

an instrumental version of a gospel song about the crucifixion of

Jesus, was sent into space on the Voyager as “the human expression

of loneliness.” The song’s full title is, “Dark was the night and

cold was the ground, on which the Lord was laid.”

Samuel

Charters wrote that Blind Willie Johnson had created a “shattering

mood” with this song. “What Willie did in the studio was to create

this mood, this haunted response to Christ’s crucifixion,” Charters

wrote, adding that Johnson created an “achingly” expressive melody

with just his slide guitar. Instead of singing the words of the

hymn, Johnson cast aside the lyrics and went for pure emotion,

humming along wordlessly in a meditative mood.

“It was

a moment that was as moving as it was unforgettable,” Charters

wrote. “It was the only piece he played like this, and nothing else

similar to it was ever recorded. It remains one of the unique

masterpieces of American music.”

Ry

Cooder said that Johnson’s performance was “the most transcendent

piece in all American music.”

Blind

Willie Johnson’s entire life prepared him to have the emotional

depth and sensitivity to create such a deeply felt response to the

crucifixion of a Biblical figure who was born homeless.

Motherless Children Have a Hard Time

Johnson’s mother died when he was an infant. One of his most moving

songs was sung with all the depth and heartache that a motherless

son could find deep within himself. It is now a classic of American

music.

His

singing sends chills through my soul. It is a darkly unsettling

experience, yet his otherworldly voice offers pure compassion to the

motherless and fatherless children of the world. I lost my own

father too early. And I love this song.

Children

who have lost their parents at a very young age may be lost on some

deep level for a very long time. And they may become lost in another

sense as well — they may become homeless or spend their childhood

days in poverty.

Every

time I hear Blind Willie Johnson sing the last verse of this song,

images arise of all the motherless and fatherless children who are

homeless in modern America, and all the throwaway kids who are

released from the foster care system with nowhere to go.

The most

haunting image that arises is a picture of Willie Johnson himself,

sightless and motherless, trying to make his way in the world by

singing these words on street corners to unseen strangers.

“Motherless children have a hard time when mother is dead, Lord.

Motherless children have a hard time — mother’s dead.

They

don’t have anywhere to go, wandering around from door to door.

Have a

hard time.”

His

father sent this sightless, motherless youth out with a tin cup to

sing on street corners in small towns in Texas. Johnson recorded for

only three years, from 1927 to 1930, yet during that time he is said

to have outsold Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues.

The Homeless Stranger

He sang

hymns and gospel songs, yet as Charter wrote, these songs “have been

so completely changed in his hands that they become his own personal

expression, building on the great Biblical figures.” Above all,

Charters added, his songs reflected “the loneliness of the

motherless child or the homeless stranger.”

One of

my favorite songs of all expresses the lonely life of the homeless

stranger. Willie Johnson walked in darkness all his life and he must

have known many lonesome days when all he met were strangers who

looked upon him as a blind beggar, a homeless stranger. They had no

way of knowing that they were meeting one of the most remarkable

musicians in American history.

But

whether we have encountered a homeless stranger, or a world-class

musician, Johnson’s song, “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger

Right,” is the voice of the conscience.

“Well,

all of us down here are strangers, none of us have no home,

Don’t

never hurt, oh, your brother and cause him to live alone.

Everybody ought to treat a stranger right long ways from home.”

His song

goes beyond a simple appeal for compassion. With his spiritual

vision, he reminds us that another Stranger once was born homeless,

because there was no room at the inn.

“Well,

Christ came down a stranger. He didn’t have no home,

Well, he

was cradled in a manger and oxen kept him warm.”

This

song is a reminder to a nation which just officially reported a

record number of more than one million homeless children enrolled in

the public schools that the lives of all of those homeless strangers

are sacred. Every single one.

Dark Was the Night

Even

though Blind Willie Johnson’s records had been selling well, and

would soon become deeply influential to other musicians, the

Depression ended the recording careers of many great blues artists,

including Blind Willie. In 1930, Johnson recorded his last song.

Yet, he kept playing music on the streets and in church gatherings

in Beaumont, Texas, all through the 1930s and up until his death on

September 18, 1945.

After

his death, his music would streak on its heroic journey towards the

stars in deep space. But during his life, this masterful musician

suffered the crucifixion of poverty. It must be said: Dark was the

night and cold was the ground on which Blind Willie Johnson was

laid.

In

August 1945, the shack where he lived with his wife Angeline burned

down. With nowhere else to go, they lived in the fire-gutted ruins

of their home and slept on wet newspapers on top of their soaked

mattress. Johnson soon died of pneumonia or, alternately, malarial

fever.

There

are so many haunting deaths among homeless people on the streets,

premature deaths caused by untreated illnesses among extremely poor

people with inadequate medical care. And there are so many haunting

deaths in the blues.

One

immediately thinks of the terrible death of Robert Johnson, slowly

and torturously dying in 1938 after being poisoned, and Charley

Patton dying on a Mississippi plantation shortly after singing “Oh

Death” at his last recording session for Vocalion in 1934.

Blind

Lemon Jefferson died alone in a snowstorm on a wintry night in

Chicago in December 1929, and Bessie Smith died in Clarksdale,

Mississippi, in 1937 following a deadly car accident while traveling

on Highway 61 from Memphis into Clarksdale. Elmore James died from a

massive heart attack in 1963 when he was only 45 and should have had

many more years to play his brilliant slide guitar.

Sonny

Boy (John Lee) Williamson I, a fine singer and groundbreaking blues

harpist, was murdered at the age of 34 during a robbery in Chicago

in 1948. His last words reportedly were, “Lord, have mercy.” Another

great vocalist and, in many people’s view, the most brilliant

musician ever to play the blues harmonica, Little Walter, died at

the age of 37 in 1968 as a result of injuries suffered during a

fight in Chicago.

Sonny

Boy Williamson II died in 1965, a short time after playing in a juke

joint with Robbie Robertson and the Hawks (later of The Band).

During the set, Williamson was constantly spitting what Robertson

thought was tobacco juice into a can, until he finally realized that

Sonny Boy actually had been spitting his blood into the can all

night, then returning to play harmonica.

Even in

light of all these tragic deaths, there is something in the

brilliant artistry and the forsaken death of Blind Willie Johnson

that is deeply touching. He lived and died a genuine,

gospel-drenched hero of the blues — not just when he was recording

his immortal music, but in my mind, maybe even more during the 15

years from 1930 to 1945 when the sightless street musician continued

to play to small numbers of strangers on obscure street corners.

How We Treat the Stranger

In

remembering his death, an unwelcome thought arises: This is how we

treat the homeless stranger. We have created a society where an

unknown blind man is turned away from a hospital and dies in a

fire-gutted home, not just in Johnson’s era in rural Texas, but here

and now, and in every state of the union.

Even

today, we scarcely notice when a slum hotel in the inner city burns

to the ground, or when homeless people die years before their time

due to untreated illnesses and exposure, or that the safety net has

been shredded so blind and disabled people are less able to survive.

Johnson

sang, “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger Right,” to warn us that

the messiah may appear in the anonymous guise of a nameless,

faceless stranger, and that the life of each unsheltered, needy

stranger has sacred worth.

Then, he

demonstrated the full significance of those lyrics by dying the

unnoticed death of the unknown stranger, even though, in this case,

he was one of the finest musicians of all time.

T.S.

Eliot’s poem, “The Rock,” echoes with the same message about the

stranger.

When the

Stranger says: “What is the meaning of this city?

Do you

huddle close together because you love each other?”

What

will you answer? “We all dwell together

To make

money from each other?” or “This is a community?”

On his recording of “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger Right,”

Blind Willie Johnson asked us that same question, a question that

will never go away.