|

A

powerful torrent of “justice blues,” as deep and wide as the

Mississippi itself, flows in an unbroken stream from the

Depression-era blues of Bessie Smith and Skip James all the way to

the 21st century blues of Otis Taylor and Robert Cray.

Cold

ground was my bed last night, rocks was my pillow too

Cold

ground was my bed last night, rocks was my pillow too

I woke up

this morning, I’m wondering What in the world am I gonna do?

— Lightnin’

Hopkins, “Mojo Hand”

Lately, I’ve

been immersed in one of the strongest currents of the blues — blues for

the downtrodden and destitute, blues for the oppressed and dispossessed,

blues for the broken-hearted and the just plain broke. A current of

music so powerful that it’s like being swept away on the flood waters of

the Mississippi River.

A mighty

torrent of “justice blues,” as deep and wide as the Mississippi itself,

flows in a long and unbroken stream from the Depression-era blues of

Bessie Smith, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Skip James all the way to the

21st century blues of Otis Taylor, Robert Cray and Charlie Musselwhite.

As I’ve

searched for songs of social justice in the history of the blues, I’ve

found anthems for the poor and homeless in every year and every decade

since blues artists were first recorded in the 1920s.

So many

great blues musicians have spoken out against injustice and inequality

that it always surprises me to read the books of scholars and critics

who write that the blues have little to do with social justice, or who

ignore this crucial issue entirely. Many historical accounts even avoid

examining the way that the blues were created by a people scarred by

slavery, suffering under segregation and subjected to a system of

involuntary servitude in the South.

Yet, all

through the nearly one hundred years of its recorded history, blues

musicians have been striking the chords of compassion and crying out for

justice. This may not be the major channel of the blues, but it is,

nonetheless, a deep and inspiring current that has always helped

hard-hit people get through tough times.

When Bessie

Smith recorded her powerful “Homeless Blues” in 1927, two years before

the Great Depression, she became the first in an unbroken line of blues

artists to hear the cry of the poor. In recent years, I’ve heard echoes

of Bessie’s blues in the haunting homeless blues of Charlie Musselwhite

and Robert Cray, and in the stinging social conscience of Otis Taylor.

It is vital

to understand why Otis Taylor’s modern blues, “Plastic Spoons,” a

heartbreaking picture of hunger and poverty in 2014, echoes so strongly

the “Hard Time Killing Floor Blues” of Skip James during the Great

Depression.

The River of Song

For a

hundred years, musicians have constantly sung the blues about the

suffering caused by hunger and homelessness, and have written compelling

songs to awaken the nation to the cry of the poor.

Their songs

flow as ceaselessly as a river that runs all the way from the blues

created in sharecroppers’ shacks in the Mississippi Delta of the 1930s

to the homeless encampments of today.

In The

Land Where the Blues Began, folklorist Alan Lomax’s account of his

journeys through the segregated South to discover and record blues

musicians for the Library of Congress, he explains why the inequality of

that long-ago era echoes the economic injustice of the present in such a

striking way.

Lomax wrote,

“Homeless and desperate people in America and all over the world live in

the shadow of undreamed-of productivity and luxury. So it was in the

Mississippi Delta in the early part of this century. Boom times in

cotton gave a handful of planters easy riches, while the black majority

who produced the cotton lived in sordid shanties or roamed from job to

job.”

The blues were born on the fields of brutality. Lomax wrote, “The

rebellious were kept in their place by gun and lynch laws, ruthlessly

administered by the propertied.”

|

“I’m Done Crying”

When

Robert Cray, a gifted blues guitarist with the deeply emotional

vocal style of a soul singer, opened a concert for B.B. King in

2012, I was absolutely blown away by his newly written song,

“I’m Done Crying,” a deeply felt and up-to-the-minute blues

about the homelessness triggered by the interlocking disasters

of unemployment and home foreclosures.

“I’m

Done Crying” is from Cray’s 2012 release, “Nothin’ But Love.” In

the CD liner notes, Cray explains, “I was writing about the

recession, about people in America who are losing their homes,

and the banks foreclosing on mortgages.”

“I’m

Done Crying” is a masterful piece of storytelling about a man

who loses his job when the company relocates overseas. He then

loses his house while unemployed — but refuses to lose his

dignity.

“I

used to have a job, but they shut it down.

Put

the blame on the union (like they always do)

and

now it’s in some foreign town.”

In

Oakland, countless well-paying, union jobs were lost due to

plant closures. The runaway corporations got rich, the workers

got shafted, and the unions got blamed. Many of those workers

ended up in homeless shelters. |

|

Robert Cray, a gifted blues

guitarist with the vocal style of a soul singer, brought the

audience to its feet when he sang about a man who lost his home

in a foreclosure. |

Every word

of Cray’s song happened in real life on the streets of Oakland. Now,

with the nationwide foreclosure epidemic, it is happening all over

America.

“They

took the house when I lost my job.

Left us

out in the street (yes they did).”

Cray went

beyond simply telling the outer truths about eviction and dislocation,

and described the inner emotional truths of what it feels like to not

only have your job and home stripped away, but to have your very

identity erased.

“I begged

for mercy, called out in pain,

No one

seems to hear me. It’s like I don’t have a name.”

It is that

verse that struck home so profoundly. No matter how many times people

may read the statistics about others losing their homes or jobs, it is

always a shock when it happens to them. Then they find out that nearly

no one cares, and that their lives no longer seem to matter.

“It’s

like I don’t have a name.”

That one

line captures this loss of soul in an unforgettable way. Cray ends the

song by vowing that he is done crying and has no more tears. He sings

out soulfully, defiantly: “You won’t take away my dignity ‘cause I am

still a man.”

The moment

he sang that line, everyone in the packed audience that night stood on

their feet, cheering in triumph. It felt as if that one lyric had beaten

down all the bankers and home mortgage companies, all the heartless

landlords and the whole urban tragedy of homelessness.

I would

swear that every single person in the audience felt at that moment that

Robert Cray was singing for all of us, and telling our story. In a voice

full of anguish, he showed us how the whole burden of plant closures and

foreclosures had fallen on the shoulders of one lone man — a man who

still keeps alive his fighting spirit and his dignity.

As the song

ended, there was an awed hush, followed by an outburst of applause and

cheering that went on and on and on.

That night,

the blues cried out in pain for all those who had lost their jobs and

homes. The song was much more than a political treatise. It was the

wounded heart of humanity crying out in the night.

Robert Cray

and the late Stevie Ray Vaughan were largely responsible for the rebirth

in popularity of the blues in the 1980s and ‘90s. Cray is a five-time

Grammy winner who plays beautifully melodic electric guitar, stinging

yet smooth, and sings in a soulful voice that blues critic Bill Dahl

says “recalls ‘60s great O.V. Wright.” (That works for me, because O.V.

Wright is one of my favorite soul singers of all time, along with Aretha

Franklin, Otis Redding, Etta James and the incomparable James Carr.)

|

Blues for the Homeless

Child

Charlie Musselwhite is a mesmerizing master of the blues

harmonica who was born in Mississippi, and grew up in Memphis

where he played with blues legends Furry Lewis, Big Joe Williams

and Gus Cannon, before moving on to Chicago and playing with

many of the all-time masters of the blues harp, including Little

Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson and Big Walter Horton.

Musselwhite’s first album, “Stand Back,” was released in 1967,

and he has been one of the most acclaimed blues musicians ever

since. Last year, I stood right next to the stage as he blasted

out his blues harp in a small club in northern California. It

was a thing of beauty to hear his command of that amplified

harmonica and his mellow, Memphis-accented vocals.

On

Musselwhite’s “Sanctuary” CD, he became a voice of sorrow and

compassion for a generation of lost and abandoned children.

“Homeless Child” is a solemn and soulful blues written by Ben

Harper (who accompanies Musselwhite on guitar).

As

Musselwhite sings in a slow, melancholy voice, somehow you

become aware of the unseen multitudes in the background of the

song — and in the background of our cities — silently appealing

for help that never arrives. |

|

Charlie Musselwhite’s blues

harmonica cries so movingly that you understand why Delta blues

legend Big Joe Williams called Musselwhite one of the finest

harp players of all time. Photo credit: Mikesfox |

“Nowhere

here to call my home, no one near to call my own

All

that’s left is for me to roam. Somebody please, help me hang on.”

In words

that cut like a knife, Musselwhite lets you know that in modern America,

homelessness is a matter of life and death, and the life of a child on

the street could end tomorrow.

“Some

will pass and some will stay. Is this the end or just one more day?

Homeless

child, homeless child, what is left for the homeless child.”

The Black Water Blues

On his

“Delta Hardware” CD, recorded in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina,

Musselwhite sings the ominous “Black Water” about the deadly flood

waters that inundated New Orleans. His voice is full of menace and

gloom, like a prophet warning of a nation’s terrible downfall, yet it

also is full of tender concern for the plight of Katrina’s victims.

“Oh black

water, our world is filled with tears.”

Charlie

Musselwhite’s song about the black floodwaters has deep roots in the

blues that stretch all the way back to Bessie Smith’s “Backwater Blues,”

a song she wrote in 1927 about the floods that reduced so many to

homelessness. Bessie sang the “Backwater Blues” for the same reasons

that Charlie sings the “Black Water” blues. She sang about the thousands

who lost their homes and had nowhere on earth left to go:

“When it

thunders and lightnin’ and when the wind begins to blow

There’s

thousands of people ain’t got no place to go.”

Flash

forward 80 years from Bessie’s blues, and Charlie Musselwhite sings that

the black waters of Katrina’s floodtides are a “sign of our times.”

After he sings that line, his mournful harmonica solo cries so movingly

and rings through so many musical changes in the span of a minute that

you understand why Delta blues legend Big Joe Williams called him one of

the finest harp players of all time.

Hurricane

Katrina was a disaster for everyone in its path, but like many natural

calamities, it struck with far more destructive impact on poor and black

people in New Orleans, who didn’t have the resources to flee the city,

and who remained destitute and neglected for years afterwards. Echoing

Bessie Smith’s song 80 years earlier, Musselwhite’s song is a

lamentation for the ones who had the least, yet were hit the hardest.

“Poor

people paying, and rich folks fleeing.

Black

water, it’s a sign of our times.”

Warning that

the wreckage caused by Katrina is “just a shadow of what’s to come,” he

sings out a doomstruck foreboding that more black waters will flood the

land — more calamities to come, more homelessness, more desperation. He

sings the unnerving final warning like a prophet of old:

“Oh black

water lapping at your door. Hello America, better get ready for more.

Trouble,

trouble all around here, we’re too tired to shed a tear.”

The Invisible Ones

One of the

most remarkable songs on Musselwhite’s “Delta Hardware” record is

“Invisible Ones,” a half-sung, half-spoken anthem for the homeless.

I love that

the song is not just an appeal for help, but is a cry for justice that

breaks the vow of silence imposed by a society that chooses to remain in

denial about the millions of poor and desperate people in our midst.

Musselwhite gives “the invisible ones” a voice of their own to accuse

the nation that has refused to even see their hungry children.

They may be

called the invisible ones, he sings, yet they “have been here all along,

right next door.” Homeless people are in every city and every state of

the nation, and they become invisible only because they are shunned.

As

Musselwhite sings, “You pass me right on the street, you just look away

and down at your feet.”

Our society

has banished these invisible ones from view and refused to hear their

cries — even when they are handed over to hunger, homelessness, and

ultimately, to death.

“You

don’t see us, you don’t even try.

Our

children are hungry, you don’t hear them cry.

‘Cause we

are the invisible ones. The invisible ones, that you left die.”

These lyrics

are not delivered as they might be by some liberal, middle-class poet

writing about poverty in the abstract, but rather as poor people

themselves would sing them, in words that bite and confront and accuse,

impolite words that break the silence and voice their anger and despair

that their children are abandoned to suffer.

Musselwhite

sings knowingly about what nearly everyone who works with poor and

homeless people has seen over and over again: the generosity and sharing

that goes on in this community. I’ve personally witnessed far more

sharing among people who are poor than among the affluent. His song

knows all about this unexpected culture of sharing.

The narrator

declares that he is of “the working poor” and goes on to tell us what

that means.

“If you

have a nickel, and I have a dime, if you are in need, I’d give you

mine.”

If there is

sharing in the friendship circles of the poor, there is cold

indifference everywhere else.

Still, the

question arises: Why shouldn’t we ignore the disturbing sight of so many

needy people? Why should we be our brother’s keeper?

Musselwhite

offers a stunning reminder: “On your front gate, you hung a sign.” At

the front gate of America in New York harbor, we hung that sign on the

Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses

yearning to breathe free.” The sign, by poet Emma Lazarus, adds: “Send

these the homeless, tempest-tossed to me.”

Yet now, as

Musselwhite sings, our nation refuses to provide a haven for the

homeless, tempest-tossed ones.

“But you

don’t see us, you don’t even try

We’re the

invisible ones who are left outside.”

|

Plastic Spoons

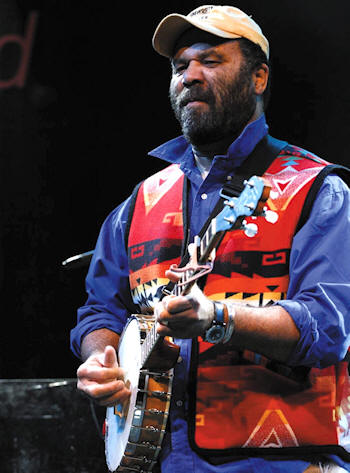

Otis

Taylor may be the most politically outspoken voice in the

history of the blues. A 21st century blues artist with deep

roots stretching all the way back to the country blues of the

Mississippi Delta, Taylor is an imaginative

multi-instrumentalist who sings and plays guitar like the primal

blues masters of old, but also creates strikingly original

rhythms on the banjo, electric mandolin and harmonica.

As

the creator of “trance blues,” Taylor is an innovator who

remains rooted in the deep blues even as he also draws on folk

and mountain music.

In

The All Music Guide to the Blues, Steve Leggett captures

Taylor’s distinctive artistry by calling him a “righteous,

fire-breathing hybrid” of reggae musician Peter Tosh and Detroit

bluesman John Lee Hooker.

Legget wrote: “Otis Taylor’s unconventional approach to the

blues has made him one of the freshest and most innovative

musicians to hit the genre in decades. His driving, modal

arrangements and defiant, politicized subject matter make most

other contemporary blues artists seem like watered-down popsters.”

On

his amazing record, “Double V,” Taylor sings about poverty and

homelessness at a level of truth so intense that it sears the

soul. In “Plastic Spoons,” it hurts to look so closely into the

eyes of a man and his wife weighed down by the double burden of

old age and desperate hunger. |

|

Otis Taylor is a uniquely

talented artist who sings the blues about homelessness, hunger,

slavery, lynchings, Native Americans, civil rights — and love. |

In the liner

notes, Taylor explains this song: “An elderly couple can’t afford

prescription medicines unless they resort to eating dog food.”

Some

might feel the song is just too emotional, on the verge of becoming

melodramatic. Yet, nothing in this song is sensationalized. Rather, it

is one of those rare songs that refuses to turn away from honestly

looking at the epidemic of hunger and misery among poor seniors in

America.

My wife,

Ellen Danchik, works with low-income and homeless seniors at St. Mary’s

Center in Oakland, a city with the highest concentration of impoverished

elders in California, and she values Otis Taylor’s unflinching honesty

in describing this desperate scene of heartache and deprivation.

“Oh, the

way they cry every night, when he watches his wife,

just

about dinnertime, eating dog food on a plastic spoon.

We can’t

make the bills. Can’t make the bills anymore.”

The

instrumentation of “Plastic Spoons” is nearly unique in the annals of

the blues. Otis Taylor sings and plays electric mandolin, his daughter

Cassie Taylor plays bass, and Shaun Diaz and Lara Turner play cellos.

Cellos and mandolin on a blues record!

The Reindeer Blues

“Reindeer

Meat” is a song equally as stark as “Plastic Spoons,” and it, too,

examines the desperate food choices that confront hungry and homeless

people.

In his liner

notes, Taylor writes: “At Christmastime, a homeless girl is certain she

would never eat reindeer meat.”

The song has

some of the expected holiday imagery: “If you see Santa Claus walking

down the street, won’t you put a penny in the can.”

But it soon

becomes clear that a homeless daughter has overheard her mother saying

they won’t even have food this Christmas. The daughter vows that,

despite her family’s lack of food, she still won’t violate the spirit of

the season.

“Mama

told me we ain’t got no food. But I ain’t gonna eat no meat.

Ain’t

going to eat no reindeer meat, especially on Christmas day.”

The Blues and the Slave

Trade

The blues

began with the most massive and oppressive system of displacement and

homelessness in American history — the slave trade. An estimated four

million human beings were held in bondage by slaveowners at the time of

the Civil War.

In The

Rough Guide to the Blues, Nigel Williamson wrote, “No account of the

evolution of the blues could be complete without an overview of how

millions of people were uprooted and displaced from their African homes

and forcibly resettled in the Americas, and of the life of misery and

hardship that awaited them there.”

The

plantation system in the Mississippi Delta “created one of the harshest

systems of slavery the world has ever seen — an unrelentingly punishing

environment that gave birth to the blues,” Williamson added.

B.B. King’s

song, “Why I Sing the Blues,” examines the deepest historical roots of

the blues.

“When I

first got the blues, they brought me over on a ship.

Men were

standing over me and a lot more with a whip.

And

everybody wanna know why I sing the blues.”

On his

“Respect the Dead” album, Otis Taylor sings “Ten Million Slaves” in a

voice nearly as broodingly intense as John Lee Hooker’s. The song

describes the ordeal of millions of African people — his ancestors — who

were put in chains and taken across the ocean on the Middle Passage to a

land they had never seen.

“Ten

million slaves crossed that ocean, they had shackles on the legs.

Food goes

bad, food looks rancid, but they ate it, anyway.

Don’t

know where, where they’re going. Don’t know where, where they’ve been.”

British

blues scholar Paul Oliver’s account of the origins of the blues in his

book, Blues Fell This Morning: Meaning in the Blues, begins with

a harrowing description of the slave system. “Over a period of three

centuries men and women in the millions were torn from their African

homeland, chained, shipped, sold, branded, and forced into a life of

toil that only ceased when death froze their limbs. Their children

worked in the fields from the day when they could lift a hoe to the day

when they dropped between the shafts of the plow.”

Millions of

enslaved workers cleared the forests and swamps of the South, and then

planted the vast acres of tobacco and cotton that enabled plantation

owners to accumulate their enormous wealth.

Countless

human beings were sold in slave markets where children were cruelly

separated from their parents, and husbands were stripped away from their

wives, never to see one another again.

Paul Oliver

wrote that the enslaved laborers were “held in perpetual, unrelenting

bondage on whom the South relied. On the results of their sweat and toil

depended its economy.”

Tall White Mansions and

Little Shacks

Neil Young

once was subjected to an enormous amount of criticism for singing that

same undeniable truth about the slave system in his song “Southern Man.”

I can’t for the life of me understand how he could have written a more

accurate description of what was really at stake.

By any

historical and economic analysis, Young’s words are factually true and

morally correct, laying bare the whole basis of the plantation economy

in a few concise lines sung with unbelievable fire and passion.

“I saw

cotton and I saw blacks, tall white mansions and little shacks.

Southern

man, when will you pay them back?

I heard

screaming and bullwhips cracking. How long? How long?”

Young has it

exactly right. The African people who were kidnapped from their homeland

and forced to live in “little shacks” created the wealth of those living

in the “tall white mansions” described in “Southern Man.” They were

forced to labor from first light to the fall of night by brutal

overseers with whips in hand.

In “When

Will We Be Paid,” their 1969 movement anthem, the Staple Singers asked

the same question that Neil Young asked: “When will you pay them back?”

Mavis Staples asked that question and sang out the truth:

“We

worked this country from shore to shore

Our women

cooked all your food and washed all your clothes

We picked

cotton and laid the railroad steel

Worked

our hands down to the bone at your lumber mill.

When will

we be paid for the work we’ve done?”

Although the

U.S. government officially apologized and made reparations for

imprisoning Japanese-American citizens in internment camps during World

War II, the Staple Singers remind us that the government has never made

amends, or paid reparations, for the horrifying crime of slavery.

Sharecropping and

Segregation

Bondage and

involuntary servitude didn’t end after the Civil War and the

Emancipation Proclamation, but continued without let-up for another 100

years, until Rosa Parks’ act of defiance sparked the Montgomery bus

boycott, and that, in turn, helped to spark a rebellion that grew into

the Freedom Movement.

After

slavery was outlawed in the United States, the sharecropping system

began, and a new form of exploitation and economic servitude began.

The blues

began as a song in the hearts of workers and prisoners laboring on the

plantations and prison grounds of Texas, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia and

Mississippi. The blues is the beautiful art form created by a people

that refused to let their voices be erased.

In Deep

Blues, one of the finest books about the emergence of the blues in

the Mississippi Delta, Robert Palmer wrote that after the Civil War

ended slavery, the sharecropping system “rapidly developed into a kind

of modern-day feudalism.”

“In theory,

the system was fair enough, but in practice it was heavily weighted

against the blacks,” Palmer wrote. “At the end of a bad year, and most

years seemed bad to some degree, the blacks wound up in debt.” Their

debts were carried over into the next year and were used to keep the

sharecroppers in perpetual servitude to the plantations.

“Families

that stayed on the same plantation year after year found that they sank

deeper into debt regardless of how hard they worked,” Palmer explained.

The

plantation system cleverly rigged the year-end economic calculations of

the worth of a sharecropper’s cotton harvest in order to enrich

plantation owners at the expense of poor tenant farmers. No sharecropper

dared question this iniquitous system too critically because the

landowners could immediately call on their armed overseers, and could

also call on the entire apparatus of local law enforcement to repress

any defiance.

At the same

time, Southern officials enacted a comprehensive set of Jim Crow laws

that imposed a system of white supremacy, enforced by cradle-to-grave

racial discrimination and secretly strengthened by extrajudicial

executions and other acts of terrorism carried out against the black

populace by the Ku Klux Klan and lynch mobs.

“The laws ostracized blacks and made them second-class citizens,” wrote

Nigel Williamson. “Formal sanctions blocked access to decent housing,

jobs, schools, hospitals and public transportation, and ensured that

African-Americans were kept unskilled, uneducated and living in poverty.

Even in death, segregation continued: many morgues and cemeteries were

white-only.”

The

Voice of the Voiceless

It is truly

amazing that one of the most important and influential art forms in

America — the strikingly original blues music that has spread around the

globe and deeply influenced rock-and-roll, soul music, jazz and country

music — was created by the poorest and most oppressed black people

living in one of the nation’s most impoverished regions.

As Palmer

writes in Deep Blues, “It’s the story of a small and deprived

group of people who created, against tremendous odds, something that has

enriched us all.” The blues were created by “the poorest, most marginal

black people,” Palmer added. “They owned almost nothing and lived in

virtual serfdom.”

If ever a

form of music has given a voice to the voiceless, it is the blues. This

music that was first sung by an oppressed people locked away in rural

isolation and held down in abject poverty — this music gave them a voice

that spread across the nation, then carried across the oceans to reach

the farthest corners of the world.

It is so

important today, when so many in our nation are once again trapped in

poverty — hungry, homeless and abandoned to live and die on the streets

— that these voices are resurrected and heard once again as they sing

about their hopes and dreams, their fears and nightmares, their quest

for love and for social justice.

Interviewed

on “The House of Blues Radio Hour,” Ray Charles described how the blues

are born in an oppressed and mistreated people.

Charles

said, “I think that the blues came from people having trouble. I think

the blues came from people being mistreated. I think the blues came from

people having bad relations with their loved ones, or being mistreated

or depressed or oppressed. The blues is a way of expressing how you feel

inside; you can sing about it and you’re getting it out of your system.”

The civil

rights movement also grew out of people “expressing how they feel

inside” about being mistreated or oppressed. That is why the blues and

the civil rights movement have always seemed linked in my mind, linked

by the history of segregation, racism and poverty that gave rise to both

of these movements.

Just as I

feel that the civil rights movement is the single most inspiring example

of nonviolent resistance ever to arise in America, I feel that the blues

and gospel music that grew out of the experience of black people in

America are the most inspiring and influential forms of music.

It is a

paradox of the human spirit that the all-time blues classics of Charley

Patton, Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters took root and flourished in the

hard soil of the southern plantation system, while Son House, Bukka

White and Robert Pete Williams created some of their most memorable

blues after serving hard time in some of the most infamous prisons in

the South.

|

Laughing to keep from

crying

Sometimes, the blues can be a way of laughing in the face of

disaster - “laughing just to keep from crying,” as classic blues

singer Virginia Liston described it in her “You Don’t Know My

Mind Blues” in the 1920s.

Louisiana Red exemplifies this strain of the blues. A gifted

singer and guitarist, and an imaginative and iconoclastic

songwriter, Louisiana Red (born Iverson Minter) has written some

of the blues most outspoken political lyrics. He has also

written some of the genre’s most darkly despairing songs and,

strangely enough, some of the most hilarious.

Death and poverty may be the least likely sources of laughter in

the world. Yet the blues can transform even these mortal enemies

of humankind and leave us “laughing just to keep from crying.”

In “Too Poor to Die,” Louisiana Red works his verbal magic on

our worst fears. |

|

Louisiana Red is an imaginative

songwriter who has written some of the blues most darkly

despairing songs, but also some of the most hilarious. Photo

credit: Till Niermann

|

“Last

night I had a dream. I dreamed I died.

The

undertaker came to carry me for the ride.

I

couldn’t afford a coffin. Embalming’s kinda high

I jumped

off my death bed ‘cause I’m too poor to die.”

Sadly

enough, Louisiana Red, seemingly an ever-lasting fountainhead of

creative guitar work and socially conscious lyrics, died in 2012 when a

thyroid imbalance caused him to fall into a coma.

It is almost

impossible to fathom this bluesman’s contradictions. His life began in

tragedy. He grew up in an orphanage after his mother died of pneumonia

just after he was born, and his father was the victim of a lynching by

the Ku Klux Klan.

So we can

readily understand that Louisiana Red would be moved to write intense,

autobiographical lyrics about growing up in an orphanage, or a searing

description of watching as his much-loved wife died of cancer in 1972.

And we might also expect Red to sing profoundly felt songs about the

many injustices he sees in the world around him.

We might

even be able to understand his performance of “Dead Stray Dog,” one of

the most unnerving song titles ever. Kent Cooper explained that he

composed the song for Louisiana Red because the plight of a dead and

abandoned dog was a stark reminder of the lonely deaths of homeless

people and wandering, nomadic blues singers on the road. The death of

the stray dog, Cooper wrote, “was not unlike hundreds of drifters and

blues singers who followed their inclinations and wound up in lonely,

unmarked graves.” Louisiana Red performed the song with deep feeling. As

Cooper wrote in the liner notes: “There are a lot of ways to die on a

road. A person cannot help but reflect on their own lives on seeing an

abandoned death, where you are going and how you’ll end. Red caught that

feeling in his singing.”

All those

expectations are more than met by Louisiana Red’s intensely felt and

highly political body of work. In fact, he surpasses our political hopes

with songs such as “Reagan Is for the Rich Man” and “Antinuclear Blues.”

Blues critic

Robert Sacre captures perfectly this side of Louisiana Red’s music,

writing in Music Hound Blues: “He is a specialist of introverted,

intense performance, living his sad stories again and crying in true

despair over emotionally charged guitar licks, well served by his great

slide playing.”

So that side

of Red we can understand. But how are we to comprehend that someone born

in the midst of such tragedy also has created some of the most

hilarious, astonishing and surrealistic blues lyrics of all time?

In an early

song, “Red’s Dream,” he casts himself as the nation’s savior, traveling

to the United Nations to straighten out the Cuban missile crisis. When a

grateful U.S. president asks Louisiana Red to come to Washington, the

bluesman tells the president that he can continue to run the country,

but Red will run the Senate! And who will he appoint to the Senate to

straighten out the nation? Blues artists!

“Oughta

make a few changes with a few soul brothers in it.

Ray

Charles and Lightnin’ Hopkins and a guy like Jimmy Reed.

Bo

Diddley and Big Maybelle be all I need!”

But somehow,

in this fickle world, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Big Maybelle were never

appointed to the Senate, and Louisiana Red left America and lived in

Germany until his death in 2012. He became another member of the small

community of expatriate bluesmen who relocated to Europe and found a

better home for their brilliant blues overseas.

Terry Messman

Editor,

Street Spirit

October 2014

See

“Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,”

Part 2 of “The Blues and Social Justice” by

clicking

here

See

Earlyblues Interview with Louisiana Red

by clicking

here

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

My

thanks to Terry Messman for granting permission to publish this article.

- Alan White,

www.earlyblues.com

If you would like to send any comments about the

article, please email me at

alan@earlyblues.com

Article © Copyright 2014 Terry Messman. All rights reserved.

Photographs individually credited or © Copyright 2014 Terry Messman. All

rights reserved.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

|