Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

British Superstitions and the Blues |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter III -

British Superstitions and The Blues The superstitions about the Hell Hounds were not the only ones to cross the Atlantic and re–appear in some guise in black folklore. Although I have labelled these superstitions 'British", many could be identified in other parts of the world in various adaptations and differing versions. It is just that the colonial period in the U.S.A. was not only dominated by the English language, but by the customs, beliefs and superstitions from the mother country. For example, the speech of the inhabitants of the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia and Florida. "... retains the flavour of the language of Elizabethan times," (1). Since "The great majority of the earlier settlers in the swamp region were English."(2), theirs would be the dominant culture and African slaves would have been more strongly influenced by British versions of superstitions, as well as retaining a vestige of their own. Around the Suwannee River basin, English–speaking people had "... migrated from Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, ... They brought with them indentured servants ... and Negro Slaves." (3). The isolation of the Okefenokee Swamp ensured that its population changed very slowly, not only regarding language, but also old ways and beliefs. Much the same could be said for the mainly rural South in the states of Mississippi, Arkansas, Texas, North Carolina, Louisiana and Tennessee. These were the main spawning grounds of the Blues singer, some time in the later part of the nineteenth century. It is no accident that a blues quoted by a then–radical blank writer included these lines:

Simpson lists some depth omens collected in the Welsh Border counties: "a dog howling in the night, a cock crowing between dusk and midnight; an owl screeching or hooting;" (5). The broken mirror is one of the widest spread superstitions in Britain while interestingly the black cat belief is reversed in the U.S.A., at least in working–class black circles. This could be a reflection of the belief on the continent, that the black cat "... is ill omened"(6). However, I am more inclined to agree with Paul Oliver that "The social position of Blacks was as often reflected in their folk beliefs as in their fear of black articles,"(7). Simpson 's first death omen concerning a dog's howl is reiterated by Hole "... few can hear a dog howling without a tremor when there is illness in the house. Dogs are supposed to be able to see the Angel of Death"(8). My father (b.1910) was quite familiar with the superstition where if a dog howled at night it meant a death will soon occur in the immediate vicinity. These beliefs reappeared. in the Southern states, little changed, "Deah's two suns uh det. Ef duh dog holluhs aw a owl holluhs,"(9). In 1935 "Casey Bill" Weldon sang:

But there is a distinct impression that the singer is going to take a hand to ensure the superstition runs true to form:

Jazz Gillum, a harmonica player, who had recorded prolifically before World War II, reflecting his popularity, continued his career until 1950. Three years earlier he included a title describing various superstitions. Some of them obviously mirrored rural black society's environment; but mixed with these were others from British shores, including the howling dog:

In the following decade, famous Chicago Blues singer, Howlin' Wolf referred to the dog omen in his usual menacing vocal style:

'Wolf', or Chester Burnett, refers to 'My right hand itches, I'll get money for which also comes from British superstition. William 'Jazz' Gillum mentioned his 'rabbit foot' in his closing verse. In the Blues, "As in English folk-lore the rabbit foot is a powerful charm for protection,"(14). This belief goes back to at least the seventeenth century in the British Isles. In Pepys there are several references to folk-beliefs which seem to indicate some sort of resistance on the part of the Diarist, to Cartesian themes, by then currently doing the rounds! On the 20th. June, 1665, he records one of several entries which mentioned his hare's foot: "Mr. Batten in Westminster hall ... showed me my mistake, that my hares-foot hath not the joint to it, and assures me he never had his cholique since he carried it about him. And it is a strange thing how fancy works, for I no sooner almost handled his foot but my belly began to be loose and to break wind; and whereas I was in some pain yesterday and tother day, and in fear of more to-day, I became very well, and so continue." (15). On the last day of the previous year, Pepys is worrying about his unusually good state of health: "But am at a great loss to know whether it be my Hare's foote, or taking every morning a Pill of Turpentine, or my having left off the wearing of a gowne."(16). The hare's foot must be the precursor of the rabbit's foot, still popular in parts of society in the 20th. century. In 1939 it was claimed that many people in England "still carry an old potato or a hare's foot as a preventive of rheumatism."(17). As Jazz Gillum indicated, the rabbit's foot transferred to the U.S.A. There it became adopted by the Blues singer. In the earlier part of this century, in the South particularly, there were many travelling minstrel shows, circuses and medicine-shows. These often featured Blues singers, as an addition to the entertainment or to attract customers for the sometimes dubious 'wares'. The most famous was the "Rabbit Foot Minstrels" in which one of the finest vaudeville-blues singers, 'Ma' Rainey, gained. some valuable experience prior to her recording debut in 1923. Three years later, Blind Lemon Jefferson, greatest of the Texas rural Bluesmen, recorded his "Rabbit Foot Blues", and in the following year Hattie Hudson made "Doggone My Good Luck Soul", a sardonic blues about superstitions generally. After claiming she is going to put a 'gold horse shoe' on her door and referring to other good luck charms, Ms. Hudson takes a side-swipe at religion as well as the old British belief:

But her view was a-typical. The more usual attitude in black communities is included in a report in 1888. "A rabbit-foot kept in the vest pocket, or worn as a charm about the neck, will ward off evil, and will, also bestow great strength upon its keeper."(19). Returning to Pepys once more, in the last entry quoted, he referred to a "Pill of Turpentine". This was on December 31st 1664 and an earlier entry indicates he had been taking turpentine pills for the whole year! "But the Doctor's discourse did please me very well about the disease of the Stone; above all things extolling Turpentine, which he told me how it may be taken in pills with great ease."(20). That was on New Year's Day and on the 17th July, he was still having trouble with 'the Stone', going back to his doctor who "... showed me the manner of eating Turpentine; which pleases me well, for it is with great ease."(21). Over three centuries later, Mrs. Violet, who was, born in West Yorkshire in 1897, gives the following recipe, which she still swears by today (1984).

"Dutch

Drops That's for bad backs: a few drops on a teaspoon in some sugar, and get it down you. That's good stuff."(22). And another more potent recipe, again for the back:

"Oil of

juniper One dram of each shaken in a bottle -- take twenty to thirty drops on sugar. That was a pretty strong un'!"(23). Turpentine was one of the by-products of timber from the once huge forests in the U.S. including the 'piney woods' covering areas throughout the Southern states. The big lumber companies employed workers to extract the fluid from the trees "obtained by slashing the trunk of the pine tree with a knife, collecting the tree resin which bled from the wound..."(24). The resin was then processed. on 'turpentine farms', first, "... hardened into crude gum, and then putting the gum into a boiler and so producing turpentine through the process of distillation."(25). This was one of the jobs, being so unhealthy and at times dangerous as well as unpleasant, that was normally "reserved" for black workers; indeed "blacks constituted three-quarters of the entire workforce employed by the turpentine industry,"(26). So turpentine was very much a part of the Blues singers' environment, particularly in Georgia, Florida and Alabama. Blues pianists would travel the circuit of turpentine farms and logging camps, which were self-contained and mobile. as part of the entertainment to keep workers from wandering off. Other parts of this entertainment included prostitutes and hard liquor. As always the Blues reflect the singers' environment, and in 1929, the ubiquitous Memphis Jug Band recorded "I Can't Stand It" which commences:

Implying, with some sarcasm, that this custom brought over from England was a cure-all for personal / social as well as health problems. A duo, in a more vaudeville-blues vein, calling, themselves 'Pigment Pete and Catjuice Charlie', took another dig at this industry by singing of the "joys" of working on "Our Turpentine Farm", recorded the same year. Although the foregoing had some practical use on both sides of the Atlantic, there were other beliefs and superstitions which made the journey over to America, whose usefulness was less obvious. Yet they persisted. Hole tells us that "A cock crowing near a house means a stranger coming,"(28). Archetypal Blues singer, from the Mississippi Delta, Charlie Patton proclaimed:

"Banty" of course refers to a bantam rooster. As early as March, 1888, it was reported that one of the beliefs from the days of slavery was that the rooster "keeps a long lookout for coming guests. If he crow toward the front door, or the back door, you can form some idea of the high or low degree of the newcomer."(30). Prior to World War II, much of the gospel music performed by blacks sounded not too unlike their Blues counterpart. Especially the recordings by street-singing, 'guitar evangelists'. The same instruments, often with the same musical approach, were used, such as the piano, harmonica, jug as well as the guitar. Many Blues singers recorded and/or sang gospel and blues. The main difference being of course the lyrics; one sacred and the other secular. So it is not surprising to find some interaction between the two. A superstition from Britain was adapted by a singer who included both musical genres in his small recorded output of just four sides. McClintock's "seeds" are the teachings from the Bible to be spread, via a person's speech and actions, throughout the world:

In Britain, certainly in rural areas, during the nineteenth century (and probably earlier) gardeners believed that "Potatoes, peas and beans planted on Good Friday are certain to thrive, for Satan's Power over the soil is then suspended."(32). For flowers the sowing time was even more critical. "Sometimes Good Friday sowing at noon precisely was advised ... and about 1858 Canon C.W. Bingham wrote that he had received from a Dorset cottage garden a Brampton stock whose excellence was attributed to Good Friday planting"(33). McClintock, in Atlanta, extended the, sowing time to every Friday and his 'seeds' to the abstract teachings of the Gospel. Another gospel item reflects a superstition that was widespread in England and also along the Welsh border. Namely, to take the pillow from a dying person's bed so that they may suffer less pain and more, peace in their last moments on earth. Simpson found that some people thought that "one cannot die while lying on a pillow or mattress containing pigeon feathers, turkey feathers or the feathers of wild birds. So when a person's death agony was unduly long, the bystanders would sometimes pull the pillow from under him to hasten the end;(34). While Hole confirms that in 1939, in England "A person lying on a pillow stuffed with doves' or pigeons' feathers cannot die, and for this reason the pillow or mattress was generally removed"(35). In 1927 the Reverend Edward Clayborn, sometimes known as the 'Guitar Evangelist' punched his message across with a rasping vocal and effortless slide guitar phrases:

Intriguingly, this verse is not included in many other versions of this traditional and very popular gospel number, including the ones by Blind Lemon Jefferson, the Norfolk Jubilee Quartet, and Blind Gussie Nesbit. The latter coming from Texas, Virginia and North Carolina respectively. Clayborn is rumoured to be from Alabama but is otherwise a biographical blank. Alabama in the 1920's was a harsh land of unrelieving poverty, outside towns like Bessemer or Birmingham, and 'progress' moved even more slowly than say in Virginia. Perhaps the retention of this British superstition represented its last stronghold in U.S. rural, black communities. Meanwhile, back with the Devil; a square lead tablet was discovered in 1892, believed to be from the I7th. century, on the Gloucester/Herefordshire border. It is now in the Gloucester Folk Museum. Inscribed on the tablet is a curse invoking devilish omens. This inscription includes "... the name 'Sarah Ellis! written backwards, symbols of sun and moon, the number '369', and the words 'Hasmodat Acteus Magalesius Armenus Licus Nicon Mimon Zeper make this person to banish away from this place and country Amen to be desier Amen"(37). In the Blues there is much superstitious belief concerning the 'numbers racket' amongst working-class blacks.

3-6-9 cropped up in dozens of Blues including recordings made by Cripple Clarence Lofton, Albert Clemens, Bumble Bee Slim and Louisiana Johnnie. Although Simpson makes no further reference to this numerical combination, it is significant that the "mark of the Beast", in Biblical terms is 666. This is divisible by 3 as is 3-6-9 which is also a multiple of this digit; added to the fact that many blues lyrics of pre-war vintage drew on Biblical sources, mainly from the Old Testament. Thus indicating an ancient source for this belief in 3-6-9 by the Blues singer, via British superstition. Another phenomenon inspired by folk beliefs from Britain is that of the 'Traveling Man'. As important in the early Blues as 3-6-9, this figure has parallels going back as far as the sixteenth century in England and Wales. "The most famous master-magician of the Border region, the hero of a well-known cycle of anecdotes is the legendary Jack 0' Kent or Jacky Kent"(40). As with Robin Hood there are various periods and possible 'candidates' ascribed to an actual person of such a name and reputation. In any event he "... was already famous by 1595," (41). Legend has it that he sold his soul to the Devil while young and as a result had super powers. One story relates "He had magic horses which galloped through the air at a fantastic speed ... People at Grosmont told how he once set out from there at daybreak to take a mince pie to the King in London, and got there in time for breakfast, with the pie still hot--"(42). Jack O'Kent could well be the original inspiration for the heroic figure in the Blues known as the 'Traveling man'. Recorded by singers such as Coley Jones from Texas and Jim Jackson from Hernando, Mississippi, it was generally associated with singers from the Piedmont area; including Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia. In 1927, Luke Jordan from Lynchburg in the latter state put his version on record as "The Traveling Coon":

Jordan's truncated syntax adding an intriguing 'primitive' feel to the song. Other verses have the Traveling Man just escaping from the Titanic and 'shootin' craps in Liverpool' when the ship hit the fatal iceberg. This Traveling Man might have magical posers but as the refrain. shows he was not invincible. Reflecting a characteristic of the Blues; that of rarely straying too far from reality. Like the master-magician, Jack O'Kent, who often out-witted the Devil, the black hero was also cunning, and kept one jump ahead of a more concrete 'devil', in the form of the white authorities; even after capture and imminent execution:

The address forms of 'coon' and 'Shine' were common amongst blacks in the earlier half of the 20th. century, although if used by whites they became offensive. Jack O'Kent used magical horses on his 80-odd mile trip to London and in another version, from North Carolina this time, the Travelin' Man is the engineer (driver) of an express train that certainly possessed magical speed:

covering at least 1O00 miles in the time it took to give his girl friend a. kiss!

Jack O'Kent

would have travelled over to southern U.S.A. either by way

of English indentured servants in the seventeenth century, the original

workers on

the plantations before the arrival of cotton and slaves, or by way of

the U.S. Eastern seaports and the transmission of sea shanties. The

latter will be covered in a further unit "Blues At Sea". Whichever the

route, in the Southern states, the Travelin' Man "... aided by

supernatural powers"(46) seems a natural successor to the British

master–magician, in the world of the Blues. Notes 1.Matschat C.H. p.14. 2.Ibid.p.13. 3.Ibid.p.14. 4,Jones L.p.p.103-I04. 5.Simpson. ibid.p.119. 6.Ibid.p.79. 7. Oliver. ibid.- p.120. "B.F.T.M." 8.Hole.ibid.p.49. 9.Georgia Workers Project.ibid.p.99. 10.Cassey Bill. 11.Ibid, 12.Jazz Gillum. 13.Howlin' Wolf. 14.Oliver.ibid.p.125. 15.0llard R.p.111. 16.Ibid.p 110. 17,Hole,ibid,p.35. 18.Hattie Hudson. 19.Jackson.ibid.p.250-. 20.Latham R.C. & W.Matthews.p.p,1-2. 21.Ibid.p.210. 22.Kightly.ibid.p.219. 23.Ibid.p.221. 24.Silvester P.p,20. 25.Ibid.p.p.20-21. 26.Ibid.p.24. 27.Memphis Jug Band. 28.Hole.ibid.p.45. 29.Charlie Patton. 30.Jackson.ibid.p.251. 3T.Lil McClintock. 32.Baker.ibid.p.76. 33.Ibid. 34.Simpson.ibid.p.p.120-121. 35.Hole.ibid.p.49. 36.Rev. Edward Clayborn. 37.Simpson.ibid.p.66. 38.01iver p.p.141 "Screening etc. 39.Kokomo Arnold. 40.Simpson.ibid.p.57. 41.Ibid. 42.Ibid.p.59. 43.Luke Jordan. 44.Ibid. 45.Virgil Childers.

46.Oliver

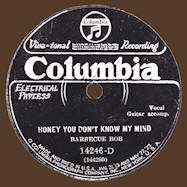

P.p.93. "Songsters etc. Illustrations Fig.1.Oliver p.p. 214 "Songsters etc.

Fig.2.Garon P.p.145. © Copyright 1992 Max

Haymes

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||