Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

British Colloquial Links and the Blues |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter III - "Origins Of Some Recorded Blues"

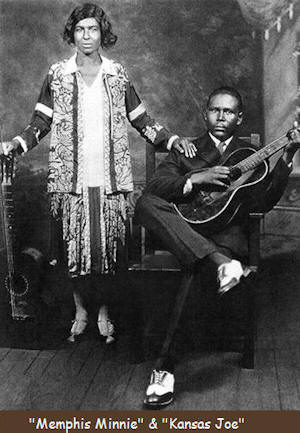

"Can I Do It For You?-Pt.2" recorded by Memphis Minnie (vo.gtr.), Kansas Joe (vo.gtr.).

As can be seen, the amorous male is not successful, even though his would-be lover accepts his final gift of one of the cars! Obviously a woman who knew her own mind and stated it openly. An early example of equality of the sexes actually being practised; which has more to do with Minnie's assertiveness and personality, rather than her husband's enlightened attitude to women. At an unknown point in time, possibly early nineteenth century, an English folk song entitled "The Silver Pin" was noted, and is performed by an unknown man and one Catherine Sue. "The Silver Pin"

Once again, the man is unsuccessful, although the woman's final response is the exact opposite to Memphis Minnie's. In the folk song, the man's intentions appear to be of a more permanent nature. However, this could have been merely a ruse to entice the woman into his bed, and Catherine Sue saw his wild offers as just a line to achieve this result. The similarities between the two songs are readily apparent; in the format of the verses and the themes employed. It is entirely possible of course, that Memphis Minnie or Kansas Joe knew of a version of "The Silver Pin" and updated their Blues accordingly. There would have been oral access, as Eaton inadvertently points out: "Old pronunciations and archaic words were also preserved by the folksongs and ballads brought from the British Isles by the colonists."(3). That the stated theme was popular in English folk song in the earlier part of the nineteenth century, is apparent by another song which extends the scenario by introducing a 'referee' or adviser called Jan. "Madam, I Will Give To Thee"

Purslow tells us that the text was collected from two sources in 1905, Somerset and Dorset. But it is quite likely that judging by the phraseology and some of the references, this song goes back to the latter part of the eighteenth century at least. The notes accompanying the above include the following: "This version is essentially intended for performance. It was sung, presumably, by three characters."(5). The theme here is of a far more romantic nature, and is almost a caricature of love, with the man and woman living happily ever after, and is almost certainly the original one. But to pursue the 'performance' theory, on an L.P. called "The Mellstock Quire" which is primarily a study of the local music scene of Thomas Hardy in his youth, we find a title "0 Jan! 0 Jan! 0 Jan!" "This is a "recension" by Hardy of a folk-piece heard by him in his very early youth. It is easily recognised as a version of "The Keys of Canterbury" and Hammond collected a fairly close analogue (H:D565). Hardy gives words, tune and manner of performance. Its curiosity lies in the fact that it was treated as a dramatic performance. Three people took the parts of the Lady, the Gentleman who tries to woo her, and the rustic Jan, who advises him. Between each exchange of the dialogue, the singers danced a three-handed reel to a tune played by the fourth performer, a fiddler. At the end of his manuscript notes, Hardy indicated that 'any 2/4 tune' could be used,..."(6). Although the reference number given by Purslow is D563, it is more than likely that the item collected by Hammond, is the one quoted above. So it transpires that the origin of "Can I Do It For You?-Pt.2" featured three singers and was musically accompanied by a fiddle. In its transition, the instrument was abandoned, only to re-appear in the form of the Blues singers' twin guitars. Whereas, Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe, themselves abandoned the "rustic Jan" when they started recording. II The next Blues covers a very different subject; that of death by hanging! Recorded some two years earlier than the first one, in 1928, by premier Texas Bluesman, Blind Lemon Jefferson, it relates the last days of a condemned murderer right up to his last seconds as the effects of hempen strangulation take over! As Lemon sings: "I'm almost dyin' gaspin' for my breath. 11 (7).

Spoken: "Thirteenth on Friday is always my bad luck day, mm! if I could find me

a hoodoo doctor,

Compare the following English folk song, collected in 1906 in Southampton:

Chorus: "Whack fol lol, lid-dle lol le day

Chorus:

Chorus:

Chorus:

Chorus:

Jack Ketch was a colloquialism for a hangman in nineteenth century Britain, which stems from earlier references to an actual person, Jack Ketch "the famous executioner of ca 1670-86."(10). The authors' note to "There Goes A Man" includes the comment "We do not know this song from elsewhere. Its rugged classic-style verses suggest an interesting origin outside the normal round of broadside publishers."(11). Blind Lemon's allusion in his spoken introduction, to "Friday on the thirteenth" is based in actual fact, as Partridge says that while in Britain, hangman's day is usually on Monday, "in U.S., "hanging day", Friday"(12). The Texas Blues singer, in his superb Blues, transposes himself into the position of a condemned murderer on his execution day, right up to his last moments. All but one of the verses deals with the physical fact of hanging, and his natural fear of it. Only in the fourth verse can he blot out the mounting panic, momentarily, to reflect on the day he was sentenced. Both songs are nearly the same length, only one verse difference, and both deal with a convicted murderer about to hang. Although it is not until the fourth verse of the English folk song, that the singer steps into his shoes. Also the George Blake song describes the events leading up to the execution day, only referring to the evil moment in the last two verses. Strangely, there is a paradox in the attitudes of the general public in Salisbury in 1906 (or earlier), and somewhere, presumably in Texas, in the Deep South in 1928. Whilst Blake can count on some support from the crowd at his hour of death, "to cheer and wipe away all weeping tears"; poor Lemon can only hear "Soon, a good-fornothin' killer is goin' to breathe his last." This could be because in the Blues title, the incident happened (if at all) in a predominantly white area, where the death of "just another nigger" was of no consequence. Such are the depths to which racialism sinks. Of course both songs probably refer to societies in the earlier part of the nineteenth century, but the paradox remains. Both songs refer to a courthouse scene; the English folk song names the location, whilst the Blues depicts the actual scene in the courtroom. Also, the opening verse to both, refer to where they are going, Blake to the prison (the first step), and Jefferson to the rope (the last step). Both singers make reference to the apparent invincibility of their subjects; the impregnability of the prison and the strength of the hempen rope. Denoting the impossibility of their situation, but at least Lemon Jefferson, via his culture, can call on the vain hope of contacting a "hoodoo doctor". Although the verses of the Blues, are of the usual three-line variety with one repeat line, as with many of the finest rural Blues singers, Lemon sings them in such a way as to make the lyrics sound as three lines in their own right. Whereas, George Blake's song contains four-line verses, but the third line is a repeat one (except verse 7) with no apparent variation, effectively reducing the song to three lines. Finally, the word "lonesome" used as an adjective, as in verse 6 of the folk item, is widely used in the southern states of the U.S.A. by both black and white populations. To be "all on one's lonesome" being a colloquialism "since ca 1890."(13). There are several possibilities when considering the routes of origin or "Hangman's Blues". It could have come from the pen of Blind Lemon Jefferson himself, quite independent of the George Blake item; bearing in mind that the latter was drawing from an on-going oral tradition. But some of the latter oral tradition was written down. Palmer includes a song called "Execution of Five Pirates for Murder", whose lyrics describe petitions and the actual 'drop' on the gallows. Based on an incident in September, 1863, the song refers to seven hangings. However, Palmer tells us: "Two were reprieved, but five hanged outside Newgate Gaol on 22 February 1864." (14). This song, in turn, may have been influenced by a street ballad from around the same year. Called "Captain Kid's Farewell to the Seas" or "The Famous Pirate's Lament", it too relates the events up to the time of his capture, conviction and final trip "in a Newgate cart" to the "hangman's tree". An intriguing but very brief reference is made in an American encyclopedia to a presumably English ballad, called in fact, "The Hangman's Tree"(15). Palmer informs us that the "The sources of these songs are oral tradition, street ballads, manuscripts and memoirs, compositions of recent date."(16), and the most important being street ballads, "from Deloney's piece on the Spanish Armada of 1588 to the anonymous 'Sorrowful Lines on the Loss of... the Titanic of 1912."(l7). Still with Newgate, whilst preparing a paper "directed against the popularity of novels and songs, of which the ruffians of the Newgate Calender were the accepted heroes."(18), a Scottish solicitor, Theodore Martin, quite by chance, received into his hand a manuscript of a recently executed killer, one Jack Fireblood. This manuscript, entitled "Flowers of Hemp" and delivered by Fireblood's hangman personally, after the execution, contained songs by several authors as well as Fireblood's own. A play which "made for months and months the fortunes of the Adelphi Theatre;"(19) was responsible for bringing, into "... vogue a song with the refrain: 'Mix my dolly (sic) pals, fake away"(20). The latter phrase, misquoted by 'Martin, is translated from cant as "Nothing, comrades; on, on," supposed to be addressed by a thief to his confederates."(21). This song was so popular that it "...travelled everywhere, and made the patter of thieves and burglars 'familiar as household words."'(22). The first verse runs:

The slang is not that obscure and translates as 'I was born in a cell of a prison and my mother's man had been hanged.' Some seven years later in 1841, the year of Fireblood's death, in the killer's own words, we have a song called "The Condemned Cell". Part of the last verse runs:

As the word "fake" is given to mean 'to steal, cheat or otherwise rob', it is more than likely that the first translation is used in its other context. So the concluding phrase in the above should read 'it's nothing, my friends, steal away'. Perhaps it was part of another Fireblood song, "The Faking Boy", which commences:

which inspired Blind Lemon Jefferson in his "Hangman's Blues". As Lemon was born in 1893 in Couchman, Texas, he would only have been a young boy when "There Goes A Man" was collected. However, some five or six years later, our hero (then a teenager) is reported playing and singing at "rough and tumble all-night parties and dances in nearby Wortham, Texas."(26), and quite possibly Lemon picked up strains of "Hangman's Blues" from an unrecorded singer.

A more likely

source for this Blues is an English folk song known as "The Prickly

Bush". "This is the usual modern form of a very ancient ballad which

Professor Child christened "The Maid Freed from the Gallows"--No.95 in

his "English and Scottish Popular Ballads". It is known in some form or

other all over Europe and North America and exists also as a prose tale

and as a "cantefable"- a prose story with sung interpolations more

often than not called "The Golden Ball".(27). The notes go on to

describe that a girl is given a golden ball and told she mustn't lose it

on pain of death. However, she loses it and in the old ballads she is

committed to burn "on a bonfire made of 'thistle and thorn' which was

the old penalty for incontinence."(28). In more contemporary ballads,

the gallows is a substitute for the fire. The notes continue, that the

golden ball may be "spirited away by supernatural forces--and she is

condemned to die unless it is recovered by a certain time."(29). To

support the ballad "The Maid Freed

from the Gallows" as the main candidate for the source of Jefferson's

"Hangman's Blues", the notes conclude: "An American negro version of the

story suggests that the, girl's plight is caused by her having taken a

"fairy" (i.e. supernatural) lover, and only his powerful intervention

can save her from her fate."(30). Paul Oliver informs us that versions

of this and other British ballads "were collected in the first quarter

of the century."(31), from black singers in the southern states.

"Several of these came from the lips of black mammies and others in

service whose contact with whites and role in the raising of children

had influenced their knowledge of traditional songs."(32). But in later

years, the recording of these ballads by blacks was only sporadic.

However, in 1934 on the Central State

In 1909, famous folk song collector, Cecil Sharp was in Somerset, where he picked up a version of "The Maid Freed from the Gallows", which included the following verses:

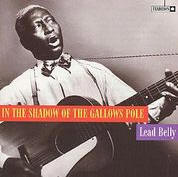

A footnote tells us that the above "...stanzas may be repeated, substituting 'mother', 'brother', and 'sister' for 'father'." (35). Leadbelly, real name Huddie Ledbetter, uses verses or stanzas which include his mother and "Lil' Martha", otherwise his wife Martha Ledbetter, arriving at the singer's imminent execution. In both songs, it is not until the arrival of the lover/wife, that the singer can be reassured that he/she have been rescued from "the gallis/us pole" in exchange for "the gold". The alternative title given on this occasion is "The Briery Bush". Although Leadbelly omits the supernatural element, Blind Lemon Jefferson does make reference to it in his spoken introduction, when he says "mm! if I could find me a hoodoo doctor, I'd make my getaway."(36). "Hoodoo" being an Americanised form of voodoo, which can be traced, via Haiti, all the way back to the African continent. An approximate chronology of "The Maid Freed from the Gallows" is shown below. Table C

I include the title "Mama, Did You Bring Me Any Silver?" as it is a strong possibility that it is yet another version of the English folk song, remaining unheard by me. But there is seemingly, an outside chance for the source being Newgate songs, and Jack Fireblood's in particular. Eaton reveals that "... during the eighteenth century over 20,000 convicts were received by Virginia and Maryland, the principal colonies to which criminals were sent."(37). Many of these convicts worked out their time as indentured servants and after their term of seven years was up, some became important public figures in Southern society. As famous author Daniel Defoe has one of his characters in "Moll Flanders" say: "Many a Newgate-bird became a great man."(38). The stream of criminals flowed on into the nineteenth century as "the port of Annapolis, Maryland, for example, showed a striking rise in the arrivals of indentured servants and convicts from England."(39). As a great majority of these immigrants were from the London area and the North of England, particularly Yorkshire."(40), they would have included a continuing supply of "Newgate-birds" who could have taken Jack Fireblood's songs with them. Of course, it is entirely possible that there were various origins of "Hangman's Blues" as Table D illustrates. Table D

Blind Lemon was obviously open to several influences for inspiration to compose his awesome "Hangman's Blues". Although the English folk song "The Maid Freed from the Gallows" looks to be the more obvious one, and it would be nice to 'pinpoint' an incident of oral transmission via Leadbelly to Jefferson, I feel that this is only part of the picture. During Lemon's wanderings around the southern states between 1917 and 1925, it would seem to be nearly impossible not for him to have heard one of Jack Fireblood's songs, if not the George Blake item itself. As Welding says "It must have been in these years of performing-- that he acquired his incredibly broad range of material--from simple chant-like songs not far removed from field cries and worksongs, through ballads and prison songs to the richly detailed, introspective blues for which he is most noted." (41). Other Blues singers picked up on Blind Lemon's chilling imagery. A couple of months after his record was issued, a fine, young woman Blues singer, Bertha 'Chippie' Hill recorded her "Hangman Blues" in Chicago. Although this remains unheard by me, I have no doubts that this is a 'cover' of Lemon's blues. Some four and a half years later, Blind Willie McTell took one step back from the hangman's rope, to record "Death Cell Blues":

Spoken: Lord have mercy.

The last line has an older English reference, as Partridge says that the noun 'crap' in cant, is translated as "... C.19 gallows:"(43), and the verb in cant as "... to hang: from ca 1780."(44). McTell is referring to the micro-second when the trap is sprung and just before eternal oblivion. With piratical bravado, he sarcastically adds that there is no point in sending him a woman, as there would not be even time to make love! Another possible route from England to Texas could have been the sea shanties, which will be explored in another Unit "Blues At Sea". Songs would have been orally exchanged between sailors and black dock workers, when the ships were being loaded and unloaded along the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. Mobile in Alabama was one of the main ports. Welding relates:" ... Jefferson has also been reported as having been in Alabama, Georgia, parts of the Eastern Seaboard and, more important to his musical development, the Mississippi Delta region."(45). It is a strong possibility that a young Blind Lemon Jefferson would have been drawn to Mobile, with its potential rewards from tired sailors, looking for entertainment as well as women, and their pay burning a hole in their pockets; on one of his visits to Alabama. © Copyright 1990 Max Haymes Addena: 1. Birtha 'Chippie' Hill's "Hangman Blues" is a cover to Blind Lemon, some 4 months later in November 1928. 2. We now know Sugarland is a state penitentiary in East Texas. 3. McTell's "Old Father Time" verse owes

its beginnings to earlier vaudeville blues singers' recordings. Notes l. Memphis Minnie & Kansas Joe. 2.Copper.p.263. 3.Eaton.p.3. 4.Purslow.p.71. 5.Ibid. 6.Notes to "The Mellstock Quire". 7.Blind Lemon Jefferson. 8.Ibid. 9.Richards & Stubbs.p.210. 10.Partridge.p.482. ll. Richards & Stubbs.ibid.p.221. 12.Partridge.ibid.p.423. 13.Ibid.p.545. 14.Palmer.p.p.245-246. 15."Encyclopedia Americana-Vol-3.p.103. 16.Palmer.ibid. 17.Ibid. 18.W.L.Hanchant.p.12. 19.Ibid.p.13. 20.Ibid. 21.Ibid.p.144. 22.Ibid.p.13. 23.Ibid-P-31. 24.Ibid.p.58. 25.Ibid.P.59. 26.Notes to "Blind Lemon Jefferson". Welding. 27.Purslow.ibid.p.141. 28.Ibid. 29.Ibid. 30.Ibid. 31.Oliver.p.229. 32.Ibid. 33.Leadbelly. 34.Karpeles.p.28. 35.Ibid. 36.Blind Lemon Jefferson. ibid. 37.Eaton.ibid.p.26. 38.Ibid. 39.Ibid.p.27. 40.Ibid. 41.Notes to "Blind Lemon Jefferson. ibid. 42.Blind Willie McTell. 43.Partridge.ibid.p.221. 44.Ibid.

45.Welding.ibid.

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

In

the preceding chapters we have seen how words, phrases, themes, etc. in

the world of the Blues have colloquial links with English and Irish

lyrics from broadsides, folk songs, poems, etc. from earlier centuries.

In this chapter we explore the lineage of an actual recorded Blues

performance, which if not the same song exactly, certainly contains the

same main theme and is an obvious parallel to the earlier works, and it

is quite possible the latter are the origins or at least the

inspirations for these particular Blues. The first Blues up for

consideration was recorded in 1930 by a then husbandand-wife team who

were often billed as "Memphis Minnie" and "Kansas Joe". The theme, a

blatantly sexual one, is that of a man wishing to make love and probably

set up some sort of semi-permanent relationship with a woman he's

attracted to. He hopes to get his way by offering her a varying range of

gifts and/or services, including two different makes of car!

In

the preceding chapters we have seen how words, phrases, themes, etc. in

the world of the Blues have colloquial links with English and Irish

lyrics from broadsides, folk songs, poems, etc. from earlier centuries.

In this chapter we explore the lineage of an actual recorded Blues

performance, which if not the same song exactly, certainly contains the

same main theme and is an obvious parallel to the earlier works, and it

is quite possible the latter are the origins or at least the

inspirations for these particular Blues. The first Blues up for

consideration was recorded in 1930 by a then husbandand-wife team who

were often billed as "Memphis Minnie" and "Kansas Joe". The theme, a

blatantly sexual one, is that of a man wishing to make love and probably

set up some sort of semi-permanent relationship with a woman he's

attracted to. He hopes to get his way by offering her a varying range of

gifts and/or services, including two different makes of car! Farm, in Sugarland, Texas, (

a correction centre), one James 'Iron Head' Baker did record "Young Maid

Saved From The Gallows." Famous folk and blues singer, Leadbelly, a

contemporary of Blind Lemon Jefferson and sang in the streets with him,

recorded "The Maid Freed From The Gallows" in the following year, for

the Library of Congress. The Library were to get him to record it again

in August, 1940, as "The Gallows Song". In between these sessions Leadbelly cut another version, for a commercial label this time,

entitled "The Gallis Pole", in 1939, part of which runs:

Farm, in Sugarland, Texas, (

a correction centre), one James 'Iron Head' Baker did record "Young Maid

Saved From The Gallows." Famous folk and blues singer, Leadbelly, a

contemporary of Blind Lemon Jefferson and sang in the streets with him,

recorded "The Maid Freed From The Gallows" in the following year, for

the Library of Congress. The Library were to get him to record it again

in August, 1940, as "The Gallows Song". In between these sessions Leadbelly cut another version, for a commercial label this time,

entitled "The Gallis Pole", in 1939, part of which runs: