Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Blues At Sea |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter

III - Blues At Sea The images of silver spades and golden chains were not the only contribution by the sea shanty to the lyrics of the early Blues. Many others came from similar sources as well as from American blacks themselves, via their work-songs. Early in the 1830's in the U.S. another musical genre appeared, the celebrated 'nigger minstrels' and 'coon songs'. This was originally popularised by Thomas Rice who would perform songs of parody in 'black face'. After his well-known performance of 'Jim Crow', many other white minstrels started to travel across the U.S. Much later, blacks themselves joined the 'minstrel scene' and songs spread across the Atlantic to Britain. (see essay "The English Music Hall Connection"). Many of the songs featured by "nigger minstrels" had their roots in the tradition of the English music hall, as has been stated. Hugill says that the influence of the "nigger minstrel" on the sea shanties is emphasized by Doerflinger who as well as listing some well-known performers, also mentions the purchase by sailors of cheap song-books of the period known as "Ethiopian Songsters." Obviously there is, via British traditions, a definite link with the emergence of the Blues in the late 19th century and the "nigger minstrels" who were prevalent during slavery times and much later, and the work-songs of the sea. To further strengthen this point, Hugill goes on to say "The following couplets are to be found both in the shanties and Negro and minstrel song and in some cases in English and American folk-songs and 'hobo songs."

Of the six couplets quoted, the above four were to re-appear, in a sometimes altered form in the world of the Blues. The third one listed has been discussed at length already (see Ch. II). The theme of No. l. has featured in the Blues as a 'floating verse' and is recalled in a title by banjoist 'Papa' Charlie Jackson on his 1925 recording "I'm Going Where The Chilly Winds Don't Blow". Blues singer/harmonica virtuoso Sonny Boy Williamson No.1. from Jackson, Tennessee, told one of his musical partners, Yank Rachell:

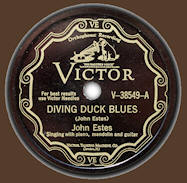

Sonny Boy Williamson reverses the usual verse-format in the Blues, the first line being repeated, whilst decrying his Chicago environment and weather, from nearby Aurora. Yank Rachell also appears in a supportive role on mandolin, with pianist Jab Jones, this time backing Sleepy John Estes, from Brownsville, also in Tennessee; when invoking the second of Hugill's couplets.

Furry Lewis, a resident of Memphis, had included a variant on his "Mistreatin' Mamma" over a year earlier, being one of the earliest examples in Blues, on record. Like the first couplet this too became a 'floating' verse and appeared in many blues; sometimes it was brandy rather than whiskey. Hugill quotes a verse from a black work-song in "American Folk Songs" (1928) by Newman I. White which runs:

And in the early 1930's the Lomaxes collected the title "'Rye Whiskey' sung by both black and white" (5) which included the verse -

- perhaps indicating its maritime origins. In the fourth and last of couplets quoted by Hugill, above, the "who's bin here?" theme appears in a blues by Mississippian Bo Carter,

The term "Jelly bean" here seems to refer to a pimp, in black slang an early equivalent of a "sharp cat" used to fast living and fast women. The melody sounds related to that of "Elder Greene Blues" by Charlie Patton in 1929. Both refer to the 'way-ward' preacher and include the phrase "... with his long coat on". As Oliver relates that "Alabama Bound" "was one of a song cluster which included ... 'Elder Green's In Town." (8), this could indicate an origin at the shanty mart in Mobile Bay. As Patton, also from Mississippi, an older man than Carter was already a big name in the South; the latter could have seen and heard him in person. Certainly other verses that appeared in the Blues were traded in the Alabamian Gulf port. A shanty called "Heave Away, Boys, Heave Away", again from Hugill, runs in part:

Victoria Spivey, from Texas, included a variant of verse 7 also found in other shanties, in her famous "T.B. Blues".

Four years later, Bo Carter, again, featured lines which were closer to those of the shanty, but obviously inspired by Ms. Spivey's big-selling record. His backache is equally as deadly as her T.B.

Verse 9 of the shanty is in much more light-hearted vein and appeared in many hokum/good-time blues in the 1930's, of the "It's Tight Like That" variety and surprisingly, perhaps, in archetypal Mississippi Delta Bluesman Robert Johnson's repertoire. Of his recorded legacy of 29 sides, he only included one in this blues genre:

The singer drawing on culinary delights for sexual imagery; a popular characteristic of the Blues. Tamales were a Mexican speciality often sold at the markets in San Antonio, where Johnson had included "They're Red Hot" as part of three sessions done in that city, in 1936. Hugill learnt the shanty from "a coloured shantyman known as 'Harry Lauder' of St Lucian, B.W. 1 in 1932." (13). He thinks that by the inclusion of the word 'heave' this shanty was "... used by the Negroes of Mobile Bay and elsewhere at the jackscrews when stowing cotton aboard the old wooden ships." (14) Probably "Heave Away, Boys, Heave Away" goes back to at least the 1870's, if not earlier. Around the same time, a roustabout song called "Shiloh" was collected by Lafcadio Hearn who only reproduced the text. "Though we do not have the music of Hearn's "Shiloh", the lyrics and imagery suggest that Negro work-song style and sea shanty style had blended plausibly." (15). Work-songs, along with 'field-hollers, were to form the nucleus of the early Blues; and many of the verses used in the work-songs continued to appear in the Blues. These verses, in turn, often being influenced by lyrics from British shores ever since the earliest days of the original Thirteen Colonies. Courlander quotes a verse from "Shiloh":

Julius Daniels from Denmark, South Carolina, "halfway between Augusta and Charleston." (17), included a variant in 1927.

Bastin suggests that Daniel's song "... sounds to be from the common ground between white and black song." (19). Around twelve years later, the harsh-voiced Tommy McClennan was a little more explicit in his version, as to the deeper meaning of the words; revenge against the white man:

Another verse from "Shiloh" is quoted by Courlander:

Veteran medicine-show singer, Frank Stokes changed the lyric from the Civil War scenario to one relating more to rural life in the South in the 1920's:

"Shiloh" was picked up on the Cincinnati water-front by Hearn in the 1870's. And as Hugill says "... many Rivermen songs ...reached deep water." (23). They also reached the Blues. An unrecorded version of the black hero ballad "Stagolee/Stack O' Lee" was noted in a report from Texas in 1910, "The song is sung by the Negroes on the levee while they are loading and unloading the river freighters, the words being composed by the singers." (24). This song was to re-surface in the 1920's on records by Blues singers such as Mississippi John Hurt, Furry Lewis, Lucille Bogan, 'Papa' Harvey Hull and 'Ma' Rainey. Coming from diverse areas as Mississippi, Memphis, Alabama and Georgia. The Lomaxes also collected some material from Polk Miller, an entertainer in the world of minstrelsy who portrayed black songs in an authentic manner. One verse they noted, runs:

But Hugill noted a shanty that was going the rounds at the birth of minstrelsy, called "Can't Ye Dance The Polka" or "the New York Gals" collected by Miss C.F. Smith. He says this shanty originated in the 1830's or 1840's "when the polka reached America from Bohemia." (26). A little more detail and variation was included in the work-song of the sea:

In 1928, a group of singers from the Memphis area put on record, a parody of an old spiritual:

Oliver would appear to agree with Hugill when he says "G. Burn Gonna Rise Again" "...included stanzas that pre-dated the Civil War!" (28), regarding the original shanty's vintage. The theme certainly seemed widespread. St Louis-based guitarist, Charlie Jordan offered another version:

Back with Hugill who came across a shanty in Trinidad in 1931 called "Miss Lucy Long":

A singer who also played guitar, on his secular sides, was Lil McClintock (Lil should read L'il as this is a male artist) who recorded in Atlanta in 1930, using quite 'early' speech patterns from the plantation days of minstrelsy and indeed from his recorded output of four sides, the other two being sacred numbers, he could hardly be classed as a blues singer, and it is due mainly to the fine bottleneck guitar of possibly Blind Gussie Nesbit that his sacred sides sound more in the Blues idiom than his secular records! Nevertheless it is interesting to note the following extract from McClintock's "Furniture Man":

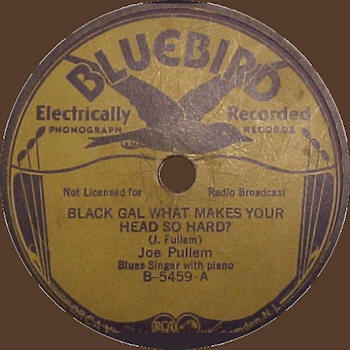

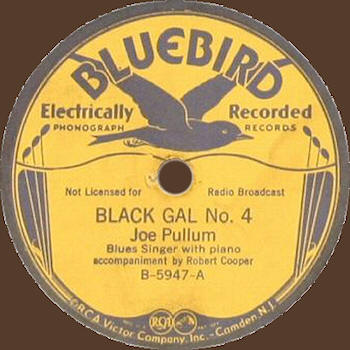

The sexual situation being transposed, on this occasion, to that of the repossession of unpaid-for goods on credit! Vaudeville-blues singer Laura Smith recorded "Lucy Long" (unheard by me) in 1925 in New York. Two years earlier, another vaudeville-blues singer Virginia Liston had cut "Sally Long Blues" referring to a dance. This dance cropped up in various blues including one by Furry Lewis, and Oliver belies the West Indies origin suggested by Hugill, of "Miss Lucy Long". He says "Though the Sally Long seems to have enjoyed a brief vogue in the late 1920's ... it's name may have been derived from the 1830's when William Whitlock and T.G. Booth sang of Sally King and Lucy Long in a dance song which included the lines "Take your time Miss Lucy Long, rock de cradle Lucy, take your time Miss Lucy Long, rock de cradle Lucy, take your time my dear", (33). Thus giving a lusty sea shanty's roots in an innocent family scene! While Mobile Bay seems to feature the most prolifically, of the Gulf ports, in sea shanties, there were stronger Blues tradition at others such as the major seaports of Houston and Galveston. During the early/middle 1930's, after a large investment of a million dollars-plus from the U.S. government "...for improvements to the Ship Canal." (33), and "...a massive Public Works Administration programme for country road development, the building of a new parcel post station in Houston, ..." (35), things started to pick up financially going against the prevailing economic trends in the U.S. generally. "Within a year or two clearing house and port accounts showed extra-ordinary increases at a time of acute financial shortages elsewhere; the peculiarities of Houston's economic recovery matched on the gulf at Galveston, led to a revival of employment and of spirits."(36). As Oliver says, this wave of optimism filtered down to the lowest social strata including the Blues singers and their audience. A strong piano tradition existed and flourished in both seaports. Artists such as Andy Boy and Rob Cooper reflected this optimism in their "... boisterous, rolling blues piano..." (37), accompanying singers such as Walter 'Cowboy' Washington and Joe Pullem. The latter was particularly popular with his working-class, black listeners. Living in Houston, he employed a falsetto style of singing which appeared new and yet retained the deep feeling of the blues. He often referred to local problems in Houston but scored his biggest 'hit' with "Black Gal What Makes Your Head So Hard?" His recording company, Victor, had Pullum back in the studios to cut "Black Gal" No.s 2, 3, & 4 before milking the tune dry.

In the 1920's there had been the remarkable Thomas family in Houston, "... Hersal and Sipple, their elder brother George, his daughter Hociel, and Bernice Edwards - no blood relation but brought up as a member of the family." (38). All sang the blues and played piano, with the young (fifteen years old!) Hersal being outstanding on the latter instrument. Although by 1935 this family had broken up, through death or moving away, 'Moanin'" Bernice Edwards was to record one more session in that year; by which time Andy Boy, Cooper, etc. were already well-established in the Houston/Galveston areas. The piano tradition was so strong that in post-war years, the great Blues singer-guitarist, Lightning Hopkins, laid down his main instrument to play the "88's" on his "Goin' To Galveston" in 1954. All of these singers and musicians, as well as scores of unrecorded names, would have been influenced by the sea and the shanties in some way or another. Andy Boy was not only a superb blues pianist but also sang. On "Church Street Blues" he was reminiscing about a Galveston locale:

"The Grinder" referred to the "Ma Grinder" which was one of a genre of barrelhouse piano pieces being "... the ragtime-derived, pre-blues music of the early part of the century." (40) Not only Blues singers who lived in and around the Gulf ports, contributed to the 'work-song exchange' or 'shanty-mart' in Hugill's words. Many recordings featured 'floating verses' with reference to the sea. The obscure guitarist, George Torey had a variant of the "went up on the mountain an' looked down in the sea" verse:

Whilst Texas supremo Blind Lemon Jefferson seemed to be the first to put these lines on wax:

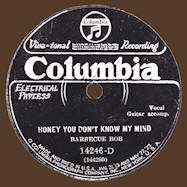

These and many other itinerant blues singers travelled all over the Southern states and would have been ideal for the spreading and perpetuating of songs via oral transmission. Together with the Blues record which extended the geographical area to cover the whole of the United States. There were recording which reflected the West Indian presence either as residents or visiting sailors at the Gulf ports. These included versions of "West Indies Blues" in 1924 by Rosa Henderson, Clara Smith and the "Home 0' Blues Trio". Henderson also recorded a "Barbadoes Blues" (sic) and a "Black Star Line" (A West Indian Chant) in the same year. Between 1925 and 1928, the Library of Congress collected a very shanty-like title from G. Carter, called "Hilup, Boy, Hilo". Some ten years later they picked up a song by Willie Carter (presumably unrelated) recorded at the State Docks in Mobile, Alabama, entitled "Captain I'm Gettin' Tired" in July, 1937. A cursory look through Godrich & Dixon's great tome of "Blues & Gospel Records 1902-1943" reveals any amount of titles alluding to the sea and sailing. Table 'D' gives a few examples by a wide range of singers and styles. Table 'D'

This is just a random sample from over 6000 titles, listed by Godrich and Dixon, of pre-war blues and there are many more which could have been included in Table 'D', from that number. At least two of the Blues listed, set off a whole cluster of later recordings, which have made the themes semi-traditional. McClennan's title (No.18) was the recorded precursor of the "Catfish Blues" which features the line "I wish I was a catfish, swimmin' down in the deep blue sea" and was recorded under this title in the same year, by Robert Petway and survives in the post-war years, being recorded by the late Muddy Waters, amongst others. Roosevelt Sykes' record (No.12) was also recorded by many pre-war Blues singers such as Walter Roland and in the post-war era by the Texas blues man, Lightning Hopkins. No.13 was an instrumental and the title implies a reference to sea shanties by their absence, as there is no vocal and therefore no singing on the 'southern seas' or the sea off the Southern states coastline. While in Kokomo Arnold's blues (No.16.) he seems to actually have been a merchant sailor, as "Here we find a graphic description of what appears to be a bad case of sea sickness:" (43), if we are to take his lyrics literally. That is the point really. In the Blues a singer does not have to necessarily experience what he/she is singing about. But as long as they are projecting situations and scenarios which are part of the common experience of their listeners, other working-class blacks, then the latter can identify with both the singer and the song. That the sea and ships, therefore by extension docks and dock workers, were part of the common experience of both listeners and Blues singers is blatantly obvious; and it is no surprise to find that shanties sung on British and American ships from the 1830's onwards, had such a strong influence on the Blues of the Southern states in the twentieth century. © Copyright 1991 Max Haymes.

All Rights Reserved. Notes:

__________________________________________________________________________

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||