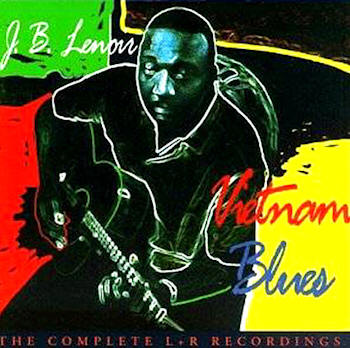

J. B. Lenoir

was one of the bravest political voices of his era. He sang against

poverty, lynching, the Vietnam War, racism and police violence in

Alabama and Mississippi.

J.B. Lenoir recorded

beautifully outspoken songs of dissent on his last two albums,

“Alabama Blues”

and “Down in Mississippi." Both records have been released as “Vietnam

Blues” on Evidence Records.

When

Michael Harrington discovered a land he called the “Other America”

in the early 1960s, he helped awaken the nation to the existence of

a vast and largely unseen subcontinent of poverty in the midst of an

affluent society. His influential book, The Other America:

Poverty in the United States, warned that 25 percent of the

people in this supposedly prosperous nation lived and died in

poverty.

Published in 1962, The Other America made an impact on

President John Kennedy, and reputedly helped to spark President

Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty.

Harrington’s book may have been an early warning signal about the

disturbing extent of poverty, yet long before he came on the scene,

African-American blues musicians had been sounding even more urgent

warnings over and over for several decades. In part, that is because

many blues artists, along with their close friends and family

members, were living in the Other America that Harrington only

described.

Many

blues musicians were able to give such powerful testimony about hard

times, discrimination, hunger and homelessness because they had

grown up in rural poverty, or lived on the poor side of town in the

crowded tenements, crumbling neighborhoods and neglected streets of

the Other America.

Blues

lyrics from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s sound today like highly

knowledgeable and up-to-the-minute accounts of the present-day

economic disparity between the rich and the poor.

The

stereotype is that history is written by the winners. Yet the

unbroken testimony of 90 years of blues lyrics amounts to a

cumulative history written by the very people thought to be

marginalized and voiceless. It adds up to a “minority report” on the

state of the nation from the streets of the Other America.

The history that can be

traced in blues lyrics tells the story of how the common people had

the soul to survive a soul-crushing system. Along with a far-seeing

awareness of economic and racial injustice, many blues songs also

express compassion and empathy towards the poor and oppressed,

especially in times when the government had ignored and abandoned

its hungry and homeless citizens.

|

Hard Times for

Floyd Jones

Floyd Jones, one of the finest singers and songwriters in

Chicago’s post-war blues circles, composed and performed

some highly politicized blues, especially unique in the

politically sluggish climate of the 1950s. His “Stockyard

Blues” told the story of workers on the picket line, and not

only sympathized with the union’s struggle for better wages

for those working in Chicago’s stockyards, but also gave

voice to the desperation of those who would have to pay

higher prices for meat.

Floyd Jones was a gifted vocalist and his dark, heavy vocals

resounded with passionate intensity, especially when he

sang, “I need to earn a dollar.” He sings the word

“need” with such forcefulness that it sounds like a

three-syllable outcry carrying all the weight of the worried

blues.

“You know I need to earn a dollar

The cost of living has gone so high,

Now then I don’t know what to do.” |

|

Floyd Jones was a

fine blues musician who wrote "Hard Times" and "Stockyard

Blues," songs about the working poor that expressed his

social conscience. |

Jones

deeply distraught vocal in “Stockyard Blues” gives voice to the

economic misery of a generation of African Americans who had escaped

the poverty and racism of Mississippi, Georgia and Alabama, only to

feel trapped in crowded slum hotels and low-wage jobs in Chicago’s

stockyards and factories.

Jones

was born in Arkansas and began playing the blues alongside such

masterful Mississippi musicians as Johnny Shines, Eddie Taylor,

Howlin’ Wolf and Big Walter Horton. Jones was part of the company of

gifted musicians who brought the intensely felt blues of the

Mississippi Delta to Chicago and created an amplified brand of

electric blues, performing in small combos at the open-air Maxwell

Street Market and in Chicago’s South Side bars and clubs.

His

beautiful music is criminally underappreciated, so much so that it

is almost painful to listen to his work today and realize that this

great musician was never given his due. In the early 1950s, Floyd

Jones made a handful of brilliant blues for the J.O.B. label,

including “Dark Road” and “On the Road Again.” He often played with

pianist Sunnyland Slim and harmonica great Snooky Pryor.

His 1954

anthem, “Hard Times,” was a soul-deep cry of anguish about reduced

hours, lowered wages, poverty and layoffs. “This is a bad time,”

sings Jones, “we laying them off by the thousands.”

In the

midst of supposed post-war affluence, Floyd Jones was a voice for

those who had been left out of the nation’s vaunted economic

progress.

“Hard

times, hard times here with me now.

If they

don’t get no better, I believe I’ll leave this town.”

Reading

those words on paper can’t come close to doing justice to the deeply

worried and agonizing vocal that Jones delivers. His impassioned

singing not only expresses his despondency at the “hard times,” but

also communicates a sense of frustration and outrage right beneath

the surface, an anger that seems close to boiling over.

If Floyd

Jones was unusually outspoken in performing these blues in such a

quiescent era, he was right in the mainstream of the electric blues

in his singing and playing. Not only is Jones a gifted singer and

guitarist, but he could put together a powerful band in the best

tradition of the Chicago blues groups headed by Muddy Waters and

Howlin’ Wolf.

In 1966,

Testament Records released an album in their “Masters of Modern

Blues” series entitled “Floyd Jones —Eddie Taylor.” Floyd Jones sang

and played guitar with the powerhouse accompaniment of Otis Spann on

piano, Big Walter Horton on harmonica, Fred Below on drums, and

Eddie Taylor on guitar. Every one of those musicians was a

world-class master. Eddie Taylor’s guitar work was the secret

ingredient that fueled blues singer Jimmy Reed’s great success for

many years. Otis Spann was the pianist in Muddy Waters’ classic

bands, and many consider him to be the finest blues pianist of all.

Big Walter Horton was, along with Sonny Boy Williamson II and Little

Walter, one of the finest blues harmonica masters of all time.

Drummer Fred Below played on nearly all of Little Walter’s hits and

was perhaps the most in-demand session drummer of his time.

That’s

the company Floyd Jones kept, yet today he is nearly forgotten.

Floyd Jones and this blues ensemble demonstrate the brilliance of

the golden era of Chicago’s electric blues in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

These artists not only brought new life to the blues, but were the

key inspiration for the Rolling Stones, Yardbirds, Animals, Cream,

Fleetwood Mac and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in England, and the

Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Johnny Winter and Canned Heat in

America.

Despite

the great commercial success enjoyed by blues-rock musicians in

England and America who were inspired so heavily by Chicago blues

musicians, the black blues masters who gave birth to this music

often could not even make a living performing the music that had

made other musicians rich.

It can

lead one to despair to realize that Floyd Jones, a beautiful and

soulful songwriter and performer, recorded so little and died in

near obscurity in 1989.

Pete

Welding, who produced the 1966 Masters of Modern Blues record, wrote

in the liner notes that Floyd Jones is “one of the handful of

excellent composers of blues to have emerged in the post-war blues

idiom.”

The very

excellence of Floyd’s work makes his fate even more incomprehensible

and bitterly ironic. It is a fate shared by many of his fellow

bluesmen.

Floyd

Jones was one of the very few musicians who spoke out for the

humanity of low-wage workers in Chicago. His songs, “Stockyard

Blues” and “Hard Times” are outspoken acts of solidarity with

workers who are screwed over by the powers that be.

And then

comes the final irony: Floyd Jones himself became one of those

screwed-over workers. Here is how Pete Welding describes it in his

liner notes:

“In

recent years, Floyd has been working as a forklift operator, the

latest in a succession of like ‘day jobs’ he has been forced to take

to support his family. It is truly a sad commentary on the state of

the blues in Chicago, where one of its finest composers and

performers cannot earn a livelihood at what he does so well.”

Tough Times for John Brim

John

Brim was another great, yet largely unheralded Chicago blues singer

and guitarist who traveled in some of the same circles as Jones. In

1953, Brim recorded one of the gutsiest and most political blues

songs of the ’50s. “Tough Times” is a classic side of tough Chicago

blues, but with a radical difference — its radical politics.

“Tough

Times” can be found on the Chess compilation, “Whose Muddy Shoes,”

which collects several wonderful and hard-to-find recordings by John

Brim and Elmore James. The liner notes report that “Tough Times”

features John Brim on guitar and vocals, his wife Grace Brim on

drums, Eddie Taylor on second guitar and Snooky Pryor on harmonica

(although elsewhere it is claimed that Jimmy Reed plays harmonica).

By

January 1954, an economic slowdown in the United States had resulted

in a nearly 10 percent unemployment rate in the black community,

nearly double the jobless rate for the rest of the nation. Brim

responded by warning that unemployment was getting as bad as the

worst part of the Depression in 1932.

“Tough

Times” has some of the tough swagger, and the stop-and-start

dynamics, of Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy,” but it couldn’t be farther

removed in its subject. While Muddy delivered a growling vocal about

discovering a powerful sense of manhood at the age of five (when his

mother said he was “gonna be the greatest man alive”), Brim’s song

describes how one’s humanity and manhood are all but destroyed by

bad economic conditions.

“Me and

my baby was talking and what she said is true.

She

said, “It seems like times is getting tough like they was in ‘32.

You

don’t have no job, our bills is past due.

Now tell

me baby, what we going to do?”

If only

this song had been heard as widely as it deserved, it might have

become that rarest of recordings — an anthem for the hard-hit

working class. For in “Tough Times,” Brim takes the side of

countless workers facing layoffs and prolonged unemployment, and the

hunger and desperation that were almost completely ignored in the

mainstream media.

Brim’s

blues are an uncompromising report from the downside of American

prosperity. Yet the song does something more important than simply

exposing the layoffs hitting countless workers at a time of supposed

affluence. His highly personal songwriting and urgent vocals make

the listener really feel the anguish of a worker whose entire

life falls apart when he or she loses a job.

“I had a

good job working many long hours a week.

They had

a big layoff and they got poor me.

I’m

broke and disgusted — in misery,

Can’t

find a part-time job, nothing in my house to eat.

Tough

times, tough times is here once more

If you

don’t have no money, you can’t live happy no more.”

Double Trouble for Otis Rush

Even

Otis Rush, the epitome of sophisticated urban blues, sang

passionately of the terrible price of layoffs and economic

hardships. In a thrillingly beautiful song he recorded in 1958,

“Double Trouble,” Rush’s voice and guitar both wail with

spine-tingling intensity as they lament how a lost job has left him

destitute.

His

singing is so intense that you believe every word when he cries out

about laying awake all night after being laid off at work. This is

the dark night of the soul, turned into a work of art by an absolute

master of the blues guitar.

“I lay

awake at night, oh so low, just so troubled.

It’s

hard to keep a job, laid off and I’m having double trouble.”

“Double

Trouble,” recorded for the Cobra label in Chicago in 1958, is

another Eisenhower-era anthem about the layoffs and lack of money

that plagued the black community in the midst of mainstream

prosperity.

Rush

sang about the same troubles that many people living in Chicago’s

slum housing had experienced — no job, no money, no decent clothes

to wear, and no sleep at night due to the worried blues.

He has

“double trouble” because being laid off and running out of money has

ended in his being rejected by his girlfriend. “You laughed at me

walking, baby, when I had no place to go.” It’s bad enough to be

homeless, walking the streets all night long, but when he sings of

being rejected in that soul-piercing voice, we feel the weight of

his torment, the “double trouble” of being broken down both

economically and romantically.

It is

amazing how much this short song reveals about the ruinous effects

of poverty. It is hard enough to undergo hunger and unemployment,

but it is maddening to suffer deprivation in a society where so many

are wealthy. The constant barrage of advertising and propaganda

perpetuate the lie that anyone can become wealthy in a consumer

society. “Double Trouble” tells the real story.

“Hey,

hey, they say you can make it if you try.

Yes, in

this generation of millionaires

It’s

hard for me to keep decent clothes to wear.”

In “The

Sound of Silence,” Paul Simon sang, “The words of the prophets are

written on the subway walls and tenement halls.” Otis Rush’s song is

one of those prophetic warnings from the tenement halls that society

ignored. When society refuses to hear its prophetic voices, it

consigns their songs to the “sounds of silence.” And any society

that neglects and abandons its poorest citizens is headed for double

trouble.

In 1958,

long before middle-class, mainstream America became aware of the

terribly destructive effects of poverty and homelessness, Rush was

singing about it in Chicago bars and blues clubs, and his warning of

double trouble was echoing up and down those tenement halls.

|

Big Mama Thornton’s

Landlord Blues

You know that times must be hard indeed just by listening to

the large number of blues songs titled “Hard Times,” “Tough

Times” or “Ain’t Times Hard.” Big Mama Thornton recorded a

shout of despair called “Hard Times” in 1952 written by the

famed rock-and-roll songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and

Mike Stoller.

Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton had a big hit with Leiber and

Stoller’s “Hound Dog,” number one on the rhythm and blues

charts for seven weeks in 1953, and Elvis Presley had an

even bigger hit with it.

Thornton was inspired by Bessie Smith and Memphis Minnie,

and she, in turn, inspired other blues and rock singers,

including Janis Joplin. Thornton’s own composition, the

great blues lament “Ball and Chain,” caused a sensation when

Joplin pulled out all the stops and turned it into a wild

cry of despair at the Monterey International Pop Festival in

1967.

Thornton was one of the premier women blues vocalists of the

1950s. On stage, she was an awe-inspiring blues shouter with

a deep, growling voice that some reviewers found menacing

and aggressive. |

|

Big Mama Thornton

was one of the premier female blues vocalists of the 1950s. |

Chris

Strachwitz, who recorded Big Mama in London while she was performing

with the American Folk Blues Festival in 1965, found that she was an

“amazingly versatile singer.” Strachwitz recorded two albums with

her backed by two different all-star blues bands: “Big Mama Thornton

with the Muddy Waters Blues Band” and “Big Mama Thornton in Europe,”

when she was accompanied by legendary blues guitarists Buddy Guy and

Mississippi Fred McDowell.

In “Hard

Times,” Big Mama Thornton delivers a powerfully convincing

performance of a woman whose life is falling apart as she trembles

on the brink of eviction. She is hounded at home as debt-collectors

and landlords knock at her door.

She

wails out the first line — “times are getting hard in the city” — as

a dark cry of desolation that seems to come from deep in her soul.

Anyone who has ever faced eviction will know how realistically she

expresses her fear and despair.

“Well I

woke up this morning, somebody knocking at my door.

It was a

man standing there, told me about the debts I owe.”

In her

misery, she tells the debt collector that she is going to just give

back everything she bought and start all over. But the hard times

are only beginning, because her next visitor is the landlord who has

come to her door to badger her for unpaid rent. She knows that this

landlord has already thrown many people out, and sings, “I know I

will be next.”

Sensing

her fate closing in on her, Thornton’s anguished singing in the

final verse conveys what it feels like when the burdens of life

become too heavy for one person to bear.

“Times

are getting hard in the city, I’m going on down the road.

With

this little money that I’m making, I can’t pull this heavy load.”

Rocks Have Been My Pillow

Melvin

“Lil’ Son” Jackson was a bluesman from Texas who played in the

traditional style of the country blues. Some writers called Jackson

a throwback to an earlier era of the rural blues. If so, what an

awesome throwback he was. Texas had a rich heritage of blues

musicians, and other writers likened Jackson to Texas bluesman

Lightnin’ Hopkins. That comparison alone is very high praise.

Similarly to Juke Boy Bonner, Lil’ Son was born into a family of

sharecroppers on a small farm in Texas. His father, Johnny Jackson,

was a sharecropper and Lil’ Son didn’t want to follow in his

father’s footsteps because he saw the injustices of the

sharecropping system.

He

escaped that existence by setting out on a musical career, recording

for Gold Star in the late 1940s and Imperial in the early 1950s. He

had several regional hits and a national hit with “Freedom Train

Blues,” but left his musical career behind in the mid-1950s to work

as a mechanic and at an auto parts store.

One of

the strengths of Lil’ Son Jackson is his story-telling ability,

delivered in a dramatic singing voice. Chris Strachwitz persuaded

Jackson to record again in 1960, and Arhoolie Records released an

excellent compilation of his music, “Blues Come to Texas.”

Strachwitz wrote that Jackson had “a beautiful guitar style and a

haunting voice.”

Many

remember Bob Marley and the Wailers singing, “cold ground was my bed

last night and rock was my pillow too,” on their “Natty Dread” album

in 1974. Twenty-five years earlier, in 1949, Lil’ Son Jackson

recorded his profoundly moving “Homeless Blues” for Gold Star

records. Jackson sang about his bed of rocks and gravel.

“Rocks

have been my pillow, baby, gravel have been my bed,

I ain’t

got nowhere, oh Lord, to lay my poor aching head.”

In the

next verse of “Homeless Blues,” Jackson describes his attempts to

hitch a ride on the highway, but finds that everyone passes him by.

“Nobody seems to know me,” he sings, as he is left deserted on the

side of the road by passing cars.

Jackson’s song is truly perceptive in capturing the feeling of being

rejected and treated like an invisible man — one of the most painful

experiences reported by homeless people. Being made to feel like an

outcast, an untouchable, adds a new level of emotional suffering to

the physical hardships of homelessness.

The

sense of feeling worthless and alone and unloved comes to a head

when Jackson adds the despair of losing a lover to the torment of

being ragged and homeless. It sounds simple to write, but it is

truly amazing to see so much meaning packed into a few short verses.

It’s a

picture of a man’s agony — and it’s the poetry of the blues at its

best.

“You

know I’m ragged and I’m dirty,

People I

ain’t got no place to go.

I know

you don’t want me baby,

Lord you

don’t love me no more.”

|

Big Bill Broonzy

Battles Segregation

Big Bill Broonzy, the man who would become one of the

best-known blues musicians in the nation, was born in Scott,

Mississippi, as Lee Conley Bradley. His parents were

sharecroppers who had 17 children. Broonzy grew into one of

the most stylistically diverse blues musicians, constantly

adapting to the times with an evolving musical approach that

stretched from the late 1920s to the late 1950s.

Broonzy began recording for Blue Bird Records in the 1930s,

and was invited to perform as a blues musician at both of

the heralded “From Spirituals to Swing” concerts held at

Carnegie Hall in December 1938 and December 1939.

After World War II, he began performing in England and

Europe and became an enormously influential musical guide to

a new generation of overseas blues fans in the 1950s. He

also returned to playing in his country blues style as part

of the folk music revival in the United States.

Broonzy died in 1958, but his life in the blues spans the

years from his 1928 song, “Starvation Blues,” to his

prophetic condemnation of Jim Crow laws at the dawn of the

civil rights era. |

|

Blues musician Big

Bill Broonzy composed some of the earliest songs about

poverty and unemployment, as well as hard-hitting songs

about racial discrimination. |

With

real foresight, Broonzy captured the economic desperation

approaching on the nation’s horizon in his “Starvation Blues,”

written in 1928, a year before the stock market crash of October

1929. Even before the Depression struck with full force, the black

community was in deep trouble and their growing poverty carried a

warning of hard times to come for the rest of the nation.

Big Bill

Broonzy’s “Starvation Blues” painted a stark picture of the hunger

and evictions that were about to sweep an unsuspecting nation.

“Starvation in my kitchen, rent sign’s on my door.

And if

my luck don’t change I can’t stay at home no more.”

“Starvation Blues” packs the entire devastation of the coming

economic collapse into a few concise lines that warn about how

unemployment would trigger a series of economic woes: hunger and

difficulty in paying the rent, followed by eviction notices and,

finally, homelessness. He described this chain reaction of poverty

even before millions were thrown out of work during the Depression.

“Man, I

ain’t got no job,

I ain’t got no place to stay.”

As the

Depression years went on, Broonzy recorded “Unemployment Stomp” in

1938. Given the grim subject matter, this song is almost

incongruously jaunty and swings with the accompaniment of trumpet,

piano and guitar, yet his lyrics are a distress signal to the

nation, a warning that unemployment and hunger will break up

marriages and families.

“Broke

up my home ‘cause I didn’t have no work to do,

My wife

had to leave me ‘cause she was starving too.”

Broonzy

already had proven farsighted in singing about the nation’s oncoming

economic collapse, and now he showed himself to be just as prescient

in confronting racial discrimination in America. He began composing

justice blues that denounced the horrible misuse of the legal system

to create oppressive Jim Crow laws.

Broonzy

had served two years in the Army, and was stationed in Europe during

World War I. In his 1928 song, “When Will I Get to Be Called a Man,”

he voiced the discontent of many black servicemen who returned from

fighting for democracy overseas, only to encounter the same racial

inequality and segregation at home.

The song

starts with a deeply moving lament about what it feels like to be a

second-class citizen, dishonored in his own country. In two

unforgettable lines, he describes how this mistreatment began at

birth and continued his entire life.

“When I

was born into this world, this is what happened to me.

I was

never called a man, and now I’m fifty-three.”

When he

returns from military service wearing his uniform, his boss tells

him that he needs to get back into his overalls and accept the same

subservient job as before — along with the same demeaning treatment.

“When I

got back from overseas, that night we had a ball.

Next day

I met the old boss. He said, ‘Boy, get you some overalls.’

I wonder

when, I wonder when, I wonder when

I will

get to be called a man.

Do I

have to wait till I get ninety-three?”

On the

liner notes of the Smithsonian/Folkways compilation CD, “Trouble In

Mind,” Broonzy describes how he wrote one of his most significant

songs, “Black, Brown and White Blues,” about his bitter experience

of on-the-job racism.

This

historically important song was written long before the Montgomery

bus boycott sparked the civil rights movement in 1954. It speaks out

so boldly about racism in America that U.S. record companies refused

to release “Black, Brown and White Blues” in this country. It was

finally recorded and released in 1951 only when Big Bill went to

Europe and a French company recorded it. It is magnificently

outspoken.

“I went

to the employment office, got a number and I got in line.

They

called everybody’s number but they never did call mine.

They

say, “If you was white, you’d be all right.

If you

was brown, stick around.

But as

you’re black, oh brother, get back, get back, get back.”

In

“Black, Brown and White Blues,” he goes on to describe the constant

victimization he faces, the lower pay based on discrimination, and

how even service in the war doesn’t lead to equal rights and

respect.

Big Bill

Broonzy’s unconquerable spirit speaks out against Jim Crow

discrimination in the song’s final line. Keep in mind that the

following verse was written long before the world had heard of Rosa

Parks and Martin Luther King.

“Now I

want you to tell me, brother,

What you

gonna do about the old Jim Crow?”

In 1956,

Broonzy performed an updated version of the spiritual, “This Train

(Bound for Glory)” with Pete Seeger, a version that can be heard on

the Folkways “Trouble In Mind” CD. Broonzy turns the familiar song

into a civil rights anthem.

“There’s

no Jim Crow and no discrimination.

This

train is bound for glory, this train.”

Eisenhower Blues

Perhaps

the most boldly political voice in the blues world of the 1950s and

1960s belonged to J. B. Lenoir, a brilliant and fearless songwriter

who took on an entire world of injustice by composing blues that

fought against poverty, lynching, the Vietnam War, racial

discrimination, police violence in Alabama and the shooting of James

Meredith in Mississippi.

In 1954,

long before anti-establishment songs became more acceptable, Lenoir

sang his outspoken “Eisenhower Blues.” His song was considered to be

so controversial that political pressure forced it to be removed

from stores and retitled as the less inflammatory “Tax Paying

Blues.”

Lenoir

sang in an unusually high-register voice, and he played acoustic

guitar in a boogie style he called “African hunch.” His voice was a

very expressive and unique instrument and he delivered powerful

performances of some of the most insightful lyrics of dissent ever

written.

“Eisenhower Blues” shows what a creative and daring wordsmith and

musician he was. Even though the powers that be forced a change in

his song’s title, Lenoir’s voice was not silenced.

“Taken

all my money to pay the tax,

I’m only

giving you people the natural facts.

I’m only

telling you people my belief

Because

I am headed straight on relief.”

With

“Eisenhower Blues,” J.B. Lenoir broke away from the manufactured

conformity of the Eisenhower era and sounded an outcry from the

people who could no longer pay their rent.

“Ain’t

got a dime, ain’t even got a cent.

I don’t

have no money to pay my rent.

My baby

needs some clothes, she needs some shoes.

Peoples

I don’t know what I’m gonna do.

Hmm, I

got them Eisenhower blues.”

The age

of Eisenhower was also the age of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his

blacklists and purges of accused dissidents. J. B. Lenoir voiced his

outspoken opposition to war and injustice at a time when dissent

could be very costly.

“Eisenhower Blues” had an element of light-hearted humor, but

Lenoir’s song, “Everybody Wants to Know,” is a radical warning to

the rich that hunger in America could spark outright rebellion.

“You

rich people listen, you better listen real deep,

If we

poor people get so hungry, we gonna take some food to eat.

Uh, uh,

uh, I got them laid-off blues.”

Many of

his finest political songs were considered too controversial to even

be released in the America of the 1950s. In his book Nothing But

the Blues, Lawrence Cohn wrote: “Lenoir’s landmark blues protest

album, ‘Alabama Blues,’ dealing with racial violence, civil rights

and Vietnam, was released only in Europe.”

German

blues festival producer Horst Lippman said, “At the time, no one was

willing to release it in America because of the political content.”

It took

the intervention of European blues supporters to allow J.B. Lenoir

to finally speak the truth about what was happening to black people

in America. In 1965, Lenoir traveled to Europe as part of the

American Folk Blues Festival.

Festival

producer Lippman wrote, “I made arrangements that J. B. Lenoir

finally should get his chance — without any limitation — to sing and

play whatever comes through his mind, whatever he might think was

and is wrong in the United States toward black people.”

Lenoir

was born in 1929 in Monticello, Mississippi, and as the 1960s began,

he would have a great deal more to say about poverty, racism and

attacks on civil rights workers in his home state.

John Lee Hooker’s No Shoes Blues

An

astoundingly high number of the nation’s most masterful blues

musicians were born in Mississippi. In Ted Gioia’s book, Delta

Blues, Detroit bluesman John Lee Hooker offered his own reason

why.

“I know

why the best blues artists come from Mississippi,” said Hooker.

“Because it’s the worst state. You have the blues all right if

you’re down in Mississippi.”

As Nigel

Williamson wrote in The Rough Guide to the Blues: “The social

and economic problems of the Delta region persist to this day, the

product and result of its history of enslavement and the legacies of

the cotton plantation era, including the Jim Crow laws, racial

segregation of public educational institutions and black

disenfranchisement.”

John Lee

Hooker was born outside Clarksdale, Mississippi, and as soon as he

came of age, he moved to Detroit, where he became one of the

pre-eminent blues musicians of his era, with hard-partying boogie

music like “Boogie Chillen,” “Boom Boom” and “Dimples.” But Hooker

also sang the “Hobo Blues” about riding the rails endlessly, and

“House Rent Boogie” about holding parties to raise the rent after

being evicted.

Perhaps

Hooker’s Mississippi roots show up most clearly in his stark and

terribly sad song, “No Shoes,” written in 1960, just as the nation

was finally beginning to become aware of the extent of hunger in

Mississippi. Hooker’s song reveals the story of hunger in America

more tellingly than any Congressional fact-finding tour.

“No food

on my table, and no shoes to go on my feet.

My

children cry for mercy, they got no place to call your own.”

Hooker’s

voice is so sympathetic and poignant, nearly sobbing about the

hunger and hardships facing his children. “My children cry for

mercy,” he sings, yet it is Hooker’s powerful, deep voice that cries

out for mercy.

It is

fascinating to hear this king of the boogie utilize his rough,

growling voice to offer such a tender and kind-hearted plea for

mercy for the children. Even his raw and primal electric guitar

sounds beautiful and mournful. It becomes another voice asking for

compassion. If ever the most rough-edged brand of Delta blues can be

said to be sensitive, this is it.

Hooker

ends his short song with an unforgettable image from the Other

America — an indictment of society’s failure to care about

malnourished children.

“No food

to go on my table. Oh no, too sad.

Children

crying for bread.”

In an interview in the

book, Elwood’s Blues: Interviews with the Blues Legends and Stars,

John Lee Hooker said, “I look at the people in the streets, sleeping

in the streets — hard time. I wonder why these people have to do

that. If we get out and reach out to those people, it would be a

better world. I can’t save the world, but I cannot forget about the

poor people working in the plants and the fields and buying John Lee

Hooker’s records. Wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be here.”

Hunting Season in Mississippi

As great

as Hooker’s song is, it would once again fall to J. B. Lenoir to

deliver the most explosive indictment of the plight of children in

the state of Mississippi. Lenoir’s song, “Born Dead” is a blues for

Mississippi, and asks a darkly disturbing question about why

African-American children are even born in a state where they will

face so much poverty, racial discrimination and lack of a decent

education.

“Lord

why was I born in Mississippi, when it’s so hard to get ahead?

Every

black child born in Mississippi, you know the poor child is born

dead.”

Lenoir

wrote that the black child born in Mississippi will never even know

his mind and will never know “why in the world he’s so poor.”

“Why was

I born in Mississippi?” That was not just a rhetorical question that

Lenoir asked in a song. Just like John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and

countless other Mississippi blues musicians who left the state of

their birth, Lenoir left Mississippi for good in the late 1940s and

moved to Chicago, where he played the blues at night and worked in

meatpacking plants during the day.

Years

after he left Mississippi and became a respected songwriter in

Chicago blues circles, the hard times he faced in the South still

weighed heavily on his mind.

In Mike

Rowe’s book, Chicago Blues, Lenoir describes why he left

Mississippi for Chicago in 1949, at the age of 20. Lenoir said, “The

way they does you down there in Mississippi, it ain’t what a man

should suffer, what a man should go through. And I said, after I

seen the way they treat my daddy, I never was going to stand that no

kind of way. So I just worked as hard as I could to get that money

to get away.”

In his

unnerving song, “Down in Mississippi,” Lenoir sang: “I count myself

a lucky man just to get away with my life.” He felt lucky to escape

with his life because of the strange and deadly nature of the

state’s “hunting season.”

“They

had a hunting season on a rabbit. If you shot him you went to jail.

The

season was always open on me: nobody needed no bail.”

|

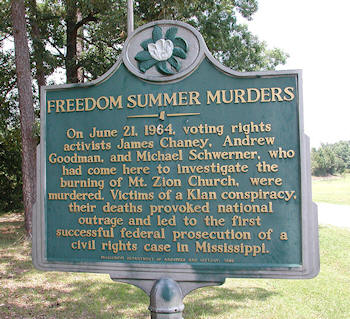

His description of the Mississippi hunting season is a

chilling reminder of the state’s history of lynchings,

shootings, and bombings, the assassination of Medgar Evers

in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1963, and the murdered bodies of

civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and

Michael Schwerner, found buried in an earthen dam in 1964.

In The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues, Giles

Oakley wrote, “Mississippi had a reputation for racism and

bigotry from the earliest days of Emancipation; its record

of lynching, reaching a bloody peak in the early days of the

Jim Crow laws, was appalling.”

Oakley added, “During the civil rights campaigns of the

1960s, the state was still a by-word for repression and

racism, with several bombings and slayings…”

Shot in Mississippi

In 1966, there was a shot heard ‘round the world in

Mississippi — the shot that nearly took James Meredith’s

life. Meredith had set off on a March Against Fear from

Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, in support of

voter registration. On the second day of his march against

racial violence, a white gunman shot him several times.

Meredith survived and several days later, 15,000 people

marched on Jackson in the state’s largest civil rights

demonstration. |

|

The Klan burned Mt.

Zion Church to the ground, and murdered civil rights

activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner

in the summer of 1964 after Schwerner and Chaney urged its

all-black congregation to register to vote.

Photograph taken by Rob Fergusonj r |

Lenoir’s

song, “Shot on James Meredith,” is a cry of outrage from the very

depths of his soul about the shooting, and a demand for the White

House to take a stand against the shooting of unarmed freedom

marchers.

“They

shot James Meredith down just like a dog.

Mr.

President, I wonder what are you gonna do now?

I don’t

believe you’re gonna do nothing at all.”

Few

musicians ever commented on this barbaric act of terror, other than

J. B. Lenoir and folksinger Phil Ochs in his brave song, “Here’s to

the State of Mississippi.” Lenoir reminded us that Meredith was

marching through Mississippi to lead the people to “what he thought

was right.”

“Last I

heard of my boy James Meredith

some

evil man shot to take his life.”

Lenoir

also wrote powerful condemnations of the violence and racism

encountered by civil rights activists in the neighboring state of

Alabama. In his song, “Alabama,” he sang about how black people —

his brothers and sisters — were murdered in Alabama, yet the state

let the killers go free.

“I never

will go back to Alabama, that is not the place for me.

You know

they killed my sister and my brother,

and the

whole world let them people down there go free.”

If

Lenoir’s voice sounds overwrought and nearly strangled by powerful

emotion while singing “Alabama,” there was good reason. In the

Alabama cities of Anniston, Birmingham and Montgomery, buses were

burned and freedom riders were brutally assaulted — several of them

beaten nearly to death — by racist mobs of white people in May 1961.

On

September 15, 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was

bombed by members of the Ku Klux Klan, killing four young Sunday

School students in the terrorist attack. In March 1965, Alabama

state troopers brutally clubbed hundreds of nonviolent demonstrators

marching for voting rights over the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo and Rev. James Reeb were all

murdered in Alabama during the Selma voting rights campaign.

Lenoir

sang out fearlessly against the killings, police brutality, bus

burnings and church bombings in Alabama that had stunned a nation.

More than that, Lenoir captured the terrible sadness that gripped

many over the tragic murders of defenseless children, ministers and

idealistic young activists. After singing that his brother was shot

down by a police officer in Alabama, he breaks down in his grief:

“I can’t

help but to sit down and cry sometimes,

thinking

about how my poor brother lost his life.”

Lenoir

responded on a very personal level to the violence directed against

the black community and civil rights workers, white and black. The

violence not only took place during civil rights protests, but had

been used for decades in Alabama as a weapon to subjugate people. By

writing in the first person, Lenoir was able to directly express his

own grief and anger over the violence. His highly emotional

involvement gave his blues their deeply felt sense of personal

identification and pain.

“Alabama, Alabama, why you wanna be so mean?

You got

my people behind a barb wire fence,

now you

trying to take my freedom away from me.”

Even in

his song “Vietnam Blues,” Lenoir can’t tear his vision away from the

violence raging at home in the South. In what at first seems to be

another of the peace anthems of the 1960s, Lenoir sings: “Oh God, if

you can hear my prayer now, please help my brothers over in

Vietnam.”

But

thinking about the war in Vietnam and praying for an end to the

killing there only serves to remind him of the need to end the

killing in Mississippi.

With

lyrics like this, J.B. Lenoir was not only a blues singer. He was a

prophet with a message of extreme importance for his country.

“Vietnam, Vietnam, everybody crying about Vietnam.

Vietnam,

Vietnam, everybody crying about Vietnam.

The law

all the day killing me down in Mississippi,

and

nobody seems to give a damn.”

Lenoir

was a man who stood up to the challenges of his time. His last two

albums, “Alabama Blues,” released in 1965, and “Down in

Mississippi,” released in 1966, are beautiful expressions of his

conscience. Both these records have been released as “Vietnam Blues”

on Evidence Records.

Tragically, Lenoir died on April 29, 1967, only a year after

releasing one of his finest recordings. He had just turned 38,

another bluesman gone long before his time. His death was reportedly

from a heart attack that may have stemmed from injuries he had

suffered in a recent car accident.

John

Mayall, one of the guiding lights of the blues in England, wrote

“The Death of J.B. Lenoir” to express his grief at the loss of his

friend.

“J.B.

Lenoir is dead and it’s hit me like a hammer blow.

I cry inside my heart that the world can hear my man no more.”