In the despairing days

after Dr. King’s death, the nation was overcome by the blues, so it

was fitting that the pre-eminent blues band in the land would play

for the activists in Resurrection City.

| |

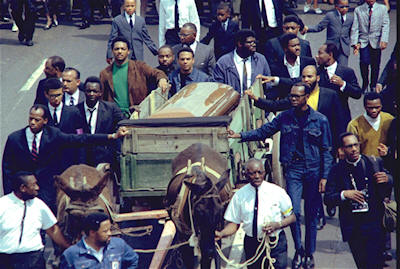

Two plow mules draw the farm

wagon bearing the casket of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

along the funeral procession route in Atlanta, Georgia,

April 9, 1968. |

|

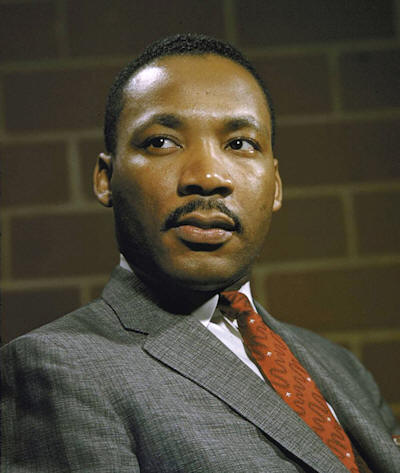

When Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated

on April 4, 1968, he was planning a nonviolent movement

aimed at winning an Economic Bill of Rights for the poor. |

Two of the

most inspiring currents in modern American history came together when

Muddy Waters and his electrifying Chicago blues band traveled to

Resurrection City in Washington, D.C., on May 18, 1968, to play a

benefit concert for the poor people and civil rights activists camped

out in a shantytown in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial.

Both of the

mighty rivers that converged on that fateful day in the nation’s capital

- the river of song and the river of justice - had their headwaters in

the state of Mississippi, in two of the nation’s most poverty-stricken

areas.

The river of

song had its source at the ramshackle wooden shack where Muddy Waters

lived and labored and first played the blues; while the river of justice

had its headwaters in Marks, Mississippi, the small town in Quitman

County where Martin Luther King, Jr. first saw the full extent of

childhood poverty and hunger.

Justice Is Like a Mighty

Stream

The two

rivers had joined together in Resurrection City, the encampment created

by the Poor People’s Campaign in May 1968. One of Dr. King’s most

oft-cited passages from the prophet Amos likens justice to a “mighty

stream.” Five years earlier, Dr. King had delivered his “I Have a Dream”

speech at the massive March on Washington in August 1963 while standing

at the same location where Resurrection City now stood. He had quoted

Amos in his speech: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness

like a mighty stream.”

King also

quoted that same biblical passage from Amos in “Letter from a Birmingham

Jail. And those same words are now carved in black granite in the

memorial to the martyrs of the Freedom Movement in Montgomery, Alabama,

the city where King helped organize the Montgomery bus boycott.

Water

constantly flows over the inscription carved in granite: “We will not

be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like

a mighty stream.” King’s name is now engraved on that memorial with

the names of 40 civil rights martyrs.

Justice

is like a mighty stream.

On May 18, 1968, six weeks after King’s murder on April 4, an endless

stream of justice-seeking activists began flowing into Resurrection City

from all over the country, traveling on the Mule Train from Marks,

Mississippi; setting out on caravans from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in

Selma, Alabama; and arriving in Washington, D.C., after 3,000-mile

journeys across the continent from Seattle, San Francisco and Los

Angeles.

Several

thousand people had made this pilgrimage for justice, and once they

arrived in the nation’s capital in May 1968, they constructed a

settlement of plywood shacks and canvas tents on the National Mall - the

first stage of their struggle for an Economic Bill of Rights for the

Disadvantaged. Dr. King’s vision of an Economic Bill of Rights included

the crucial elements needed to overcome poverty, hunger and

homelessness: full employment, decent housing for all, and an adequate

income for disabled people and those unable to work.

Civil rights

supporters around the nation were traumatized and grief-stricken after

Martin Luther King’s murder, yet several thousand people had fought off

their sorrow and outrage and had come to Resurrection City in a valiant

effort to be faithful to the last, best dream of the slain civil rights

leader - the Poor People’s Campaign.

In those

doomstruck and despairing weeks following King’s death, the nation

itself was overcome by the blues, so it was symbolically fitting that

the pre-eminent blues band in the land would play for the activists

camped out in the nation’s capital.

Blues from the Mississippi

Delta

On the day

after King’s assassination, Otis Spann, arguably the greatest blues

pianist of all and a mainstay of Muddy Waters’s band, had performed two

newly composed blues for the fallen civil rights leader - “Blues for

Martin Luther King” and “Hotel Lorraine” - in a storefront church in

Chicago, even as buildings were burning all around the church in the

riots that erupted after the fatal shooting.

Now, six

weeks later, on May 18, 1968, Muddy Waters, Otis Spann, harmonica master

Little Walter and bassist Willie Dixon had driven all night from Chicago

to play a benefit concert at Resurrection City at the invitation of

folklorist Alan Lomax, the man who had first recorded Muddy Waters for

the Library of Congress in the summers of 1941 and 1942.

Lomax had

recorded Waters playing the blues in front of his primitive wooden shack

on the Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale, Mississippi, where Muddy had

lived for 17 years picking cotton and corn and driving a tractor for

miserably low wages.

Now, in a

remarkable historic parallel 27 years after that first recording

session, the stark wooden shack that had been home to Muddy Waters on

the Mississippi plantation was mirrored in the hundreds of primitive

plywood shacks and tents erected by activists working with the Southern

Christian Leadership Conference to fulfill Martin Luther King’s vision

of a nonviolent insurrection for economic justice.

All these

powerful currents of history flowed together and met at the base of the

Lincoln Memorial in front of the Reflecting Pool on virtually the same

site where Dr. King had earlier delivered one of the most momentous

speeches in U.S. history at the massive March on Washington for Jobs and

Freedom.

Now, five

years later, Muddy Waters stood on the same spot, playing the blues for

a nation mourning Rev. King’s murder.

“Lord I’m

troubled, I’m all worried in mind.

And I’m

never being satisfied, and I just can’t keep from crying.”

The very

first time Muddy Waters was ever recorded in 1941, he sang those words

on a song that can be heard on “The Complete Plantation Recordings.”

Now, 27

years later, in 1968, those lyrics seemed to be a haunting description

of the grief in the souls of countless people who were left badly shaken

by the murder of Martin Luther King, and the recent assassinations of so

many others who had given their lives for peace and justice.

Just as

Muddy Waters sang, their hearts were “troubled” and they were “all

worried in mind” by the loss of Martin Luther King. Many felt it might

prove to be a fatal blow to the Freedom Movement, yet as they listened

to Muddy Waters sing at Resurrection City, the blues once again were a

lifeline.

And who

better to play the blues for the poverty rights activists living in the

D.C. shantytown than Muddy Waters, one of the most influential masters

in the history of the blues, and a man of the people who had known

poverty while growing up in a shack himself.

Waters had begun developing

his brilliant slide guitar technique and enormously powerful vocal style

while living in the Mississippi Delta. In 1943, he left the plantation,

jumped aboard a train heading straight out of segregated Mississippi,

and journeyed to Chicago where he put together a band of the finest

blues musicians, including rhythm guitarist Jimmy Rogers, harmonica

genius Little Walter, and the matchless blues pianist Otis Spann.

Blasting the Blues at

Resurrection City

Lomax

described the impact of Muddy’s performance in Resurrection City in

The Land Where the Blues Began.

“Back of the

poetry that expressed their discontent rose the big sound that Muddy and

his friends had been cooking up, the sound of their new wind, strings,

and percussion combo. It had many voices: a closer-miked harmonica,

wailing and howling in anguish and anger like the wind off Lake

Michigan; Muddy’s lead guitar, with the bottleneck crying out the blues

all up and down the six strings, a rhythm guitar behind, both amplified

by big speakers so every crying note, every beat could be heard a

quarter mile away … and swanking it on a grand piano, Otis Spann,

filling in all the cracks with surging boogie.”

When Waters

was first recorded, he was playing an acoustic guitar on the plantation,

but in Chicago, the country blues had been transformed into a brand of

urban electric blues that wailed with far greater amplification. But it

still expressed the primal spirit of the blues from the Mississippi

Delta, the blues Muddy had learned to love from his first musical hero

and his greatest influence, Son House.

Muddy’s

music was rooted in the Delta, and Lomax wrote that it went all the way

back “through Son House to the one-stringed diddly bow, to the very

roots of African-American music in Mississippi.”

Now, in the

fullness of time, Waters had brought the spirit of the Delta blues to

Washington, D.C., invited by the same man who had first recorded him

playing his bottleneck guitar on the Stovall Plantation. As Muddy’s band

blasted the blues for the nation at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial,

Lomax described the impact that his hard-charging music had on the

poverty activists assembled there:

“The audience, folks from the

ghettoes of the Midwest and the Deep South, knew this sound. It was

theirs. They had danced it into being on a thousand, thousand nights in

barrooms and at houseparties. Now the old Delta music, rechristened

rhythm and blues, was on stage in the nation’s capital. A roar of

applause swept across the Reflecting Pool into Lincoln’s marble house.

The politicians might not be listening, but soon the whole world would

be dancing to this beat and singing these blues.”

Senator Robert Kennedy visited the

Mississippi Delta in 1967 where he found children

starving in windowless shacks, and saw the urgent need to combat

poverty.

Robert Kennedy’s

Assassination

Many of

those who had heard the cry of the poor had responded by traveling the

long, hard road to Resurrection City. Thousands of poverty rights

activists had been battered by grief and anger and despair over the

murder of Martin, beaten by the police in a hundred demonstrations for

civil rights that had led up to this historic confrontation, and

battered over their entire lifetimes by the twin assaults of racism and

poverty.

When the

Poor People’s Campaign finally arrived in the nation’s capital to

confront the legislators who had allowed tens of millions of American

citizens to languish in poverty, they were besieged by unrelenting

rainstorms that transformed Resurrection City into Mud City.

The

demonstrators stood their ground through the rest of May and the first

weeks of June, but even as they tried to pick up the pieces and renew

their commitment in the broken-hearted days after Rev. King’s murder,

Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles on June 5, a demoralizing

and nearly unendurable death, especially since Kennedy was one of the

originators of the idea of a Poor People’s Campaign.

After he had

witnessed at first hand the shocking level of poverty, illness,

malnutrition and childhood deprivation in Mississippi, Robert Kennedy

and civil rights leader Marian Wright Edelman had encouraged Martin

Luther King to bring poor people to the nation’s capital “to make hunger

and poverty visible.”

Already

reeling from the murder of Dr. King, the poor people’s movement had been

camped in Resurrection City for less than three weeks when they learned

that Robert Kennedy had just been shot to death.

Bobby

Kennedy’s funeral procession passed through Resurrection City on its way

to his burial at Arlington National Cemetery, and as it passed by the

Lincoln Memorial, the mournful gathering sang “The Battle Hymn of the

Republic.”

Two of the

nation’s most prominent champions of poor people - and two of its most

outspoken antiwar voices - had been silenced. “Crucifixion,” an eloquent

song by protest singer Phil Ochs, poetically described the age-old

assassination of prophets, who were almost predestined for crucifixion

because they were “chosen for a challenge that is hopelessly hard.”

The road

ahead to peace and justice in America now indeed seemed hopelessly hard

- and endlessly tragic.

Then, in the final chapter of

Resurrection City, the activists who had kept their faith and hope alive

for so many long years, even in the face of tragic assassinations and

countless police assaults on the movement, were tear-gassed by their own

country’s troops and, on June 24, subjected to mass arrests and

evictions by the police and the National Guard.

|

The Epic Journey of

Muddy Waters

Those who had come by caravan and mule-drawn wagons to

Washington, D.C., had traveled many long, perilous roads. But

Muddy Waters had traveled for decades en route to playing the

blues for the Poor People’s Campaign. It was one of the truly

epic journeys - a hard-traveled highway of historic

significance.

On

the evening of May 17, 1968, the day before he was scheduled to

play the blues for the poorest of the poor, Waters and his band

had set off on an all-night car trip from Chicago, reaching

Resurrection City the next morning, on May 18.

Yet

that was only the last leg of his historic journey. Muddy’s real

odyssey began long before that. He had traveled the nation’s

highways for 25 years on his way to bringing the blues of the

Mississippi Delta to lift the spirits of the activists gathered

in Resurrection City.

His

journey began at the Stovall Plantation in the Mississippi

Delta, where he had worked as a field laborer picking cotton and

corn, and then as a tractor driver. While living in Clarksdale,

Waters had been greatly inspired by the impassioned bottleneck

guitar and the deeply emotional vocals of Son House, one of the

foundational masters of the Delta Blues. House is my favorite

musician in the entire history of the blues. |

|

The great blues musician Muddy

Waters grew up in a humble wooden shack on the Stovall

Plantation near Clarksdale, Mississippi. |

In The

Land Where The Blues Began, Alan Lomax recounts how he asked Waters

where he had first heard the song that became Muddy’s “Country Blues.”

Waters

answered, “I learned it from Son House; that’s a boy that picks a

guitar. I been knowing Son since (19)29. He was the best. Whenever I

heard he was gonna play somewhere, I followed after him and stayed

watching him. I learned how to play with the bottleneck by watching him

for about a year. He helped me a lot. Showed me how to tune my guitar in

three ways...”

It is

wondrous to consider this direct transmission of the blues from Son

House to Muddy Waters. By studying Son House’s music for so long, and

emulating this early master of the Delta blues, Waters became a direct

lineal descendant of this deeply rooted strain of Mississippi blues.

‘His Voice Is in the Wind’

Son House

had labored on southern plantations, preached in Baptist churches, and

served hard time in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm penitentiary.

House’s impassioned blues were “created in the infernal laboratory that

was segregated, Depression-stricken Mississippi,” and “embody the

alienation and isolation of the modern condition, whatever the

listener’s cultural background,” as Tony Russell and Chris Smith wrote

in The Penguin Guide to Blues Recordings.

House sings

with unbelievable fervor and his intense, raw-edged slide guitar is the

perfect accompaniment to his harsh, raging vocals.

Rolling

Stone’s

music reviewer David McGee captured perfectly the passionate intensity

of House’s slide guitar, writing that rather than employing intricate

polyrhythms or complex single-string solos, House fiercely attacked his

guitar and made it wail with unsettling intensity so that it howled

alongside his singing.

McGee wrote:

“House wielded his slide as if it were on the left hand of God: It

slashed, it wailed, it howled, it moaned, it wept.”

House died

in 1988, but his guitar and voice have never been silenced. They live on

as a permanent gift and inspiration to the blues artists that followed

in his path, beginning with Muddy Waters. David McGee wrote, “His legacy

is a body of work rarely equaled, never surpassed. His guitar is in the

Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi; his voice is in the

wind.”

Folklorist

Alan Lomax and musicologist John Work followed that wind through

Mississippi in 1941, and made some deeply valuable recordings of Son

House for the Library of Congress.

House then told Lomax about

Muddy Waters, and Lomax traveled to Clarksdale to make the first

recordings of Waters at the Stovall Plantation in 1941 and 1942. When

Muddy first heard his voice on those recordings, he finally realized

that he truly was a blues singer.

In May of

1943, less than a year after his final recordings for the Library of

Congress, Waters left his job at the plantation for good after the

overseer refused to raise his pay as a skilled tractor driver from 22

1/2 cents an hour to 25 cents.

The rest is

history. Muddy Waters boarded the train for Chicago, and never looked

back. He went on to electrify the world, creating an influential model

of highly amplified urban blues - born on the Mississippi Delta and then

alchemically transformed during countless late-night sessions in

Chicago’s blues clubs.

Muddy Waters

and Chicago’s other blues masters - Little Walter, Otis Spann, Howlin’

Wolf, Hubert Sumlin, Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson, Jimmy Reed, Big

Walter Horton, et al - then began traveling all over America and Europe,

helping to give birth to rock and roll, jump-starting the British

Invasion, and ultimately inspiring music lovers all over the world with

their brilliant artistry that transcended all barriers of race, class

and nationality. They electrified the entire world.

Martin Luther King Witnesses

Childhood Poverty in Mississippi

In 1964,

Martin Luther King, Jr. described the significance that blues and jazz

music held for the Freedom Movement in a brief article written for the

Berlin Jazz Festival. King wrote: “The Blues tell the story of life’s

difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they

take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come

out with some new hope or sense of triumph. This is triumphant music.”

King went on

to describe how significant and liberating that music had been to many

activists in the Freedom Movement. “Much of the power of our Freedom

Movement in the United States has come from the music. It has

strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It

has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.”

Just as the

Delta blues first came to life in Mississippi, so did the Poor People’s

Campaign. This attempt to build a nonviolent uprising for economic

justice first become an overwhelmingly urgent priority for Martin Luther

King after he visited Marks, Mississippi, a poverty-stricken town in the

Delta, in 1966.

King had

come to Mississippi after civil rights activist James Meredith had been

shot three times by shotgun blasts on the second day of his personal

“March Against Fear” that began on June 6, 1966. Meredith had planned to

march from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, but Aubrey James

Norvell, a white assailant, gunned him down. Norvell would later plead

guilty to the shooting.

Blues

musician J.B. Lenoir sang out his outrage over the shooting in his song,

“Shot on James Meredith.”

“June the

6th, 1966, they shot James Meredith down

Just like

a dog.

Mr.

President, I wonder what are you gonna do now?

I don’t

believe you’re gonna do nothing at all.”

In outraged

response to the shooting, thousands of civil rights activists came to

Mississippi to carry on the spirit of Meredith’s march, and Meredith

himself recovered from the shooting and was able to rejoin the march as

15,000 demonstrators entered Jackson on June 26.

During the

March Against Fear, an elderly marcher, Armistead Phipps, died of a

heart attack, and King traveled to Marks to preach at his funeral.

Martin Wept

During his

first visit to Marks, according to Hilliard Lawrence Lackey’s book,

Marks, Martin and the Mule Train, Dr. King was moved to tears by the

“pervasive sense of hopelessness and widespread hunger” he witnessed in

Marks.

King wept

again during his second visit to Marks in 1966 when he witnessed a

teacher feeding her young students a slice of apple and a few crackers

for their lunch. Public schools in many southern states had refused to

accept federal aid for school lunches in their attempts to avoid federal

integration laws.

Marian

Wright Edelman described King’s reaction to these encounters.

“Dr. King

uncharacteristically broke down in tears and had to leave the room.

Later, he said to Dr. Abernathy, “I can’t get those children out of my

mind... We can’t let that kind of poverty exist in this country. I don’t

think people really know that little school children are slowly starving

in the United States of America. I didn’t know it.”

Edelman also

accompanied Senator Robert Kennedy on a trip to Mississippi. Edelman

wrote that when Kennedy saw the poverty and hunger there at first hand,

“his profound shock and sadness motivated him to act too.” Kennedy’s

visit to Mississippi put hunger on the national agenda, and resulted in

a coalition that became active on childhood hunger, malnutrition and

illness, she explained.

Mule Train from Marks

The vision

of the Poor People’s Campaign was to make poverty and hunger and slum

conditions visible to federal lawmakers and to the entire nation. Due to

King’s heartbreaking encounters with malnourished children in Marks,

Mississippi, the small Delta town was chosen as an important symbolic

starting point for the Poor People’s Campaign. Ralph David Abernathy

later wrote that Dr. King wanted the campaign to start “at the end of

the world” - meaning in the impoverished town of Marks.

Perhaps the

most well-remembered image of the entire Poor People’s Campaign was the

Mule Train that left Marks, Mississippi, on May 14, 1968, on a

thousand-mile journey to Washington, D.C. Twenty-eight wagons pulled by

56 mules arrived in the nation’s capital on June 19, and went on a

procession down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Although it

arrived more than two months after King was assassinated, Abernathy

wrote that the “Mule Train fulfilled one of Dr. King’s dreams.”

Blues for the Dreamer

It is deeply

instructive to listen to the poignant blues songs written in response to

Dr. King’s murder, and thereby learn how people from the grass roots of

the black community - people who were not activists or political figures

- expressed their heartfelt reactions to the death of a leader, and the

loss of a man they considered a friend.

It enables

us to see that everyday people had found so much hope in King’s

courageous activism, and held so much love for him. It allows us to see

how deeply they had shared his dream, and how shattering his death was

for them.

Activists

and political theorists have argued ever since about whether “idolizing”

King takes away from the message that it is the people who build the

movement, and not just the charismatic leaders. That is true in many

cases.

Yet, in this

case, the honest and immediate reactions to King’s assassination

demonstrate how much reverence and love people held for him, and what an

irreplaceable and prophetic role he played in their lives. Those

reactions went far beyond the expected levels of grief and encompassed

everything from the outrage that erupted in widespread rioting to the

love that was expressed in so many unforgettable blues songs.

The murder of Dr. King

brought forth heartfelt elegies from Otis Spann, Big Maybelle, Champion

Jack Dupree, Big Joe Williams and Nina Simone. (We will look at Nina

Simone’s brilliant songs about civil rights, freedom and equality,

racism in America, the “backlash blues,” injustice in Mississippi, and

the murder of “the King of Love” in a later chapter of Street

Spirit’s series on The Blues and Social Justice.)

|

Heaven Will Welcome

You, Dr.King

Big

Maybelle, born Mabel Louise Smith in Jackson, Tennessee, was one

of the finest rhythm and blues singers of the 1950s and ‘60s,

with a big, beautiful voice that could joyfully roar out in

soulful celebration, yet could also deliver sensitive renditions

of finely nuanced ballads. It is difficult to fully describe her

vocal talents without sounding like a contradiction in terms,

because Big Maybelle usually growled out the blues in a

gravel-voiced roar, yet could shift gears to sing in touching

and lovely tones.

Big

Maybelle drew on both dimensions of her vocal talent to record

an extraordinarily moving elegy, “Heaven Will Welcome You, Dr.

King.” (Her song can be heard on the CD compilation, “Big

Maybelle: The Rojac Years.”)

Although she roars through this hard-rocking lament with

unbelievable passion, she also demonstrates how a powerful voice

under perfect emotional control can be sensitive enough to

express the sadness and grief in the hearts of many.

Maybelle’s singing is so strong that it rocks the foundations of

the world - just as King’s death rocked a nation to its core.

Yet, at the same time, she sings as tenderly as a mother who has

lost her child. |

|

Big Maybelle, one of

the finest blues singers of the 1950s and ‘60s, sang the moving

tribute, “Heaven Will Welcome You, Dr. King.” |

Big Maybelle

begins her lament with shocked disbelief at the loss of Dr. King. It is

a deeply felt reminder of how hard it was for people to believe that

“the King of Love is dead,” as Nina Simone described King’s death in her

own anthem.

When Big

Maybelle sings with so much love and grief and urgency, she takes us

right back to the time when the nation first learned of King’s death and

tried, in those heart-stopping moments of devastation, to comprehend how

much had been lost.

“It just

don’t seem real, that’s all I can say.

I can’t

believe Dr. King has passed away.”

It is

heartbreaking when she sings, “I can’t BELIEVE that Dr. King has passed

away.” Her sorrowful voice breaks into a sob right after the word

“believe.” The immense power of her singing is made all the more

expressive due to the scarcely controlled catch in her voice.

In my mind,

this is the finest tribute to Martin Luther King of all, and Big

Maybelle’s bighearted voice may be the only instrument strong enough to

carry the weight of an entire nation’s heartache and outrage and tears.

In fact, Big Maybelle’s heart and voice were big enough to bear the

sorrow of the entire world. That is precisely what she does in singing

this final verse.

“The

whole world! The whole world is going to miss you!

This is

true! And I know heaven, heaven is going to welcome you.”

Maybelle’s Expression of

Faith

Big

Maybelle’s song is also the most spiritually profound and the most

deeply consoling of all the songs written in the aftermath of King’s

murder. She moves seamlessly from her outrage at the “great waste” of a

great man who was needed by his people, into a beautiful expression of

her faith that he has gone to a much better place.

She sings, “I

know you’ve gone - you’ve gone to a much better place.”

Her anger is

vivid, her grief and shock and anguish are shouted out with all the

power of her being, and yet her tender affection for King spills through

every verse she sings. It somehow leads her to the same affirmation of

faith in heaven that was at the heart of Rev. King’s life and faith and

activism.

Her song

carries out a fascinating transformation of one of the most common

lyrical themes in the blues. The determination to not be defeated or

broken by the blues can be found in the songs of virtually every blues

artist. True to form, Big Maybelle tells Dr. King “don’t worry” and

“never feel blue.”

But Maybelle

doesn’t simply adapt this common blues theme to fit her song about King.

Rather, she TRANSFIGURES it into an extraordinarily powerful message

about faith. She can tell Dr. King to never feel blue because of her

faith-filled certainty that he will be welcomed in heaven.

“So don’t

worry, never feel blue.

Dr. King,

I know heaven, heaven is going to welcome you

Oh yes it

will.”

And Big Maybelle still has

another prophetic lesson to offer the world. Now that the dreamer has

fallen to an assassin’s bullet, those of us who are left behind must

carry on his work for justice.

“You served God’s

purpose and now you’re gone.

Those of us who are

left, in your name, must try to carry on.

There’s one more

thing, oh Lord, I would like to say.

Those of us who are

lucky, Lord, will see you again one day.”

Even to this day, after

hearing her song so many times, I am still amazed how, in just a little

over three minutes, Big Maybelle expresses an entire nation’s outpouring

of love and sorrow and anger, and then goes beyond that to teach us so

much about life, about death, about finding the strength to carry on

after so great a loss - and about faith in heaven and the spiritual

conviction that death will not have the final answer.

“Those of us who are

lucky are going to see you again one day.” Listening to Maybelle

sing those words, I am reminded of how much our nation learned - and how

much I learned - from the Freedom Movement led by African-American

people in the South. I learned nearly everything I know about

nonviolence, nearly everything I know about building a movement of

resistance. I also learned so much about the power of love and faith.

Big Maybelle’s song

conveys so much of what the great gospel singers rooted in the black

churches taught us. She sings with tremendous power and conviction,

“Dr. King, I know heaven is going to welcome you. Oh yes it will.”

Her singing has the

emotional depth of the blues and the spiritual depth of the gospel music

created in the African-American churches. Both these forms of music -

blues and gospel - come together beautifully in the way Big Maybelle

roars out the lyrics, “Heaven will welcome you, Dr. King.

She shouts out the word

“heaven” with all the vocal fury and passion of great Mississippi blues

singers like Son House and Howlin’ Wolf. Her voice is full of despair

and heartache and loss, an emotionally expressive outcry that only the

greatest blues shouters could match.

Yet, in that same voice -

a voice with all the soul-fire that the best blues singers ever

possessed - she also reaffirms all the love and faith in God expressed

in the great gospel songs.

‘I’ve Been to

the Mountaintop’

On April 3, 1968, on the

day before his death, Rev. King told the congregation of a church in

Memphis, “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” I cannot help but believe that

Big Maybelle’s voice was powerful enough, and resounded far enough, to

reach that mountaintop.

Right after four Sunday

School students - Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson

and Denise McNair - were killed when their Birmingham church was

destroyed by the Ku Klux Klan’s dynamite, Martin Luther King talked

about faith. After his own home was bombed, Rev. King talked about

faith. And after King himself was fatally shot in Memphis, Big Maybelle

picked up the fallen torch and sang about faith.

Big Maybelle, one of the

most powerful blues shouters of all time, was transformed, for the

duration of this awe-inspiring song, into a pastor, a caregiver for the

nation’s soul.

Her spirit rose to the

occasion with a performance that is heartbroken, but still believing.

She is enraged and outspoken, but still gentle and comforting. Her song

is both an elegy and, at the same time, a freedom song in the best

tradition of the Freedom Singers who gave so much strength to the

Freedom Movement.

We can only thank God for

giving Big Maybelle a voice big enough and glorious enough to roar out a

freedom song that transforms heartbreak into fierce determination.

“Those of us who are left, in your name, will try to carry on,” she

sings.

Labor organizer Joe Hill’s

famous statement, “Don’t waste any time mourning, organize!” is supposed

to be inspiring, yet it always has seemed somewhat lacking and

incomplete. It does inspire us to carry on the struggle, yet it tends to

reduce us only to political beings. When you lose someone near and dear

to you, a mere slogan to keep up the good fight doesn’t fully take into

account the depth of the human soul. Unless we’re merely political

automatons, more than that is at stake.

Why can’t we mourn and

organize? Big Maybelle’s song seems so much deeper to me, so much more

soulful and human-hearted. It gives full voice to our sadness and

tenderly expresses how much we miss the loved ones we have lost, while

also expressing an unbroken determination to carry on the struggle for

freedom.

I’ll always treasure Big

Maybelle’s sweetly sorrowful voice singing the simple, yet profoundly

deep truth of our loss:

“The whole world is going to miss you.”

Terry Messman

Editor,

Street Spirit

December 2014

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

My

thanks to Terry Messman for granting permission to publish this article.

- Alan White,

www.earlyblues.com

If you would like to send any comments about the

article, please email me at

alan@earlyblues.com

Article © Copyright 2014 Terry Messman. All rights reserved.

Photographs and artwork individually credited or © Copyright 2014 Terry Messman. All

rights reserved.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

|