Blues

singers have always drawn on their environment for inspiration in their lyrics

as well as in the sound of their instruments. Unlike the traditional folk singer

who will often sing of events that happened many years previous to their own experience

-sometimes referring to events spanned by centuries. Such is the case with the

execution ballads of Captain Kidd from the l7th. Century for example. It is true

there are a handful of “blues ballads” such as “John Henry”, “Stack

0’ Lee” or Frankie & Albert/Johnnie”, which have persisted in black

song but they are the exception to the rule - the vast majority of blues

reflected their surroundings in the “here and now”.

So

a pianist or guitarist would imitate the rhythms of the train wheels in the

late l9th. Century, which finally resulted in boogie-woogie. They would also

mimic the fireman ringing his bell, while the harp blower reproduced the

lonesome sound of the train whistle as it sped through the Southern countryside.

The bobbing movements of logs floating downstream to the sawmill, are

brilliantly captured by Charlie Patton’s guitar on his “Green River

Blues”; reflecting his days in the logging camps in Mississippi. But one of

the first sounds to inspire a blues singer was a natural one - the sounds of a

bird singing.

A

story handed down by ex-slaves claims

that one evening a slave was feeling low in spirit and heard a plaintive cry of

a night bird. The sound inspired the slave to get a piece of cane from a

canebrake and cut some holes in it. He then commenced to play a “blues” on

his whistle. As time went by, the instrument evolved into a set of “quills”.

One definition of a quill runs: “a piece of reed used by weavers”(1). Paul

Oliver quotes a report by U.S. writer, George Cable, in 1886 which refers to a

“black lad” cutting 3 reeds from “the edge of the canebrake.. .blowing and

hooting, over and over,"(2). Cable stated that blacks called these 3 reeds

“quills”. On l2th April 1927, Big Boy Cleveland recorded 2 quill solos, for

Gennett, one of which was issued. “Quill Blues” which lets the instrument

“sing” the blues, could not have been too far removed from the l7tn.Century

ex-African slave in the canebrake. An almost unique example on record,

significantly, Cleveland’s only other issued side featured vocal and guitar,

in the style of Furry Lewis. For this reason alone, I suspect, the only

“fact” stated about Cleveland is that he could have been from Memphis

Tennessee. which was Furry’s home base and an important centre for the Blues

in the 1920s.

The

only other example of quills or “pan-pipes” as they became known (from

”Pan’s pipes”) on a commercial blues record was by the Texas songster,

Henry Thomas. Also known as “Rag Time Texas”, he started recording some 3

months after Cleveland’s session and played a set of pan-pipes on a rack

around his neck while also playing guitar. He featured this combination for

nearly half of his issued output of 23 sides. The technical term for quills or

pan-pipes is a syrinx. One definition of which is “the organ of voice in

birds.”(3). U.S. blues writer, Sam Charters, description runs: “Each

“pipe” is a cross blown cane reed, held against the lips while the player

blows across the opening in the top, just as a child blows on an empty bottle.

The pitch of the reed is determined by its length - the shorter the reed the

higher the sound - and usually the player binds a group of them together in a

row, holding them together with pieces of stick.”(4).

Engineers in early locomotives

in the l9th.Century had a set of pipes for a train whistle, also called

‘quills’. The most famous being Casey Jones on the Illinois Central. Freeman

Hubbard relates that “By “valving”, or changing the pressure of steam

admitted into the quill, engineers could change the tones and even play

tunes”.(5). These train whistles were mounted “ahead of the smokestacks and

using parabolic amplifiers.”(6), around 1890,when Casey Jones was stamping his

own individuality on the Delta landscape. Jones “had a home-made six-chime

whistle with six slender tubes bound together, the shortest being exactly half

the length of the largest. With its interpretive tone, the “ballast scorcher”

could make the quill say its prayers or scream like a banshee.” (7). obviously

inspired by black singers using the quills or syrinx, like Henry Thomas and Big

Boy Cleveland, Casey’s “plaintive moans” could be heard right up to that

fateful day in 1900. It was at Vaughan, Mississippi. that around the curve came

another I. C. passenger train and “Number Four stabbed ‘im in the face"(8),

as Furry Lewis recalled some 28 years later, for Victor records.

Replacing

the pan-pipes/syrinx/quills, by and large, certainly by the 1920s on record,

blues singers started using the harmonica or “mouth-harp”. This being a more

flexible instrument and better suited for dancing at picnics and what Leadbelly

called 'sukey jumps’. One harp-blower with a unique style which featured

screaming through his instrument, was George ‘Bullet’ Williams. Originally

from Alabama, Williams included superb train imitations and also an atmospheric

“The Escaped Convict" at his only session in 1928. The latter title

referred to the harsh convict-lease system in the South, which was still on the

Alabama statute book in 1930! Oliver refers to the “baying hounds and pounding

feet copied on the harp” (9), when discussing William’s skill and artistry.

Replacing

the pan-pipes/syrinx/quills, by and large, certainly by the 1920s on record,

blues singers started using the harmonica or “mouth-harp”. This being a more

flexible instrument and better suited for dancing at picnics and what Leadbelly

called 'sukey jumps’. One harp-blower with a unique style which featured

screaming through his instrument, was George ‘Bullet’ Williams. Originally

from Alabama, Williams included superb train imitations and also an atmospheric

“The Escaped Convict" at his only session in 1928. The latter title

referred to the harsh convict-lease system in the South, which was still on the

Alabama statute book in 1930! Oliver refers to the “baying hounds and pounding

feet copied on the harp” (9), when discussing William’s skill and artistry.

Casey’s

home-made whistle,

in Casey Jones Museum in Jackson, Tennessee.

Intriguingly, from the same

state came the Birmingham Jug Band who recorded 9 sides at a single session in

1930; including ‘Cane Brake Blues”. This consisted of a series of 1-line

verses and points to an embryonic form of the more usual 3 line format found in

the Blues. The harp player, unidentified, has been suggested as Jaybird Coleman,

based in Birmingham, Alabama. Together with the obscure Ollis Martin, these

musicians form the nearest to a “blues tradition” in Alabama, as Oliver

suggests.

Burl

Coleman, born in 1896 in Gainsville, Alabama, used the name of a common bird in

the South, for his pseudonym as a blues man. As did pianist, Thomas Jones, who

recorded simply as “Jaybird” in 1928 when he

accompanied “Keghouse” for 10 sides, He also recorded for Library of

Congress in 1941 and 1942. Jaybird Coleman recorded a remarkable series of

vocal/harmonica blues in 1927 - 193O, closely related to the archaic field

holler which goes back to the beginning of the Blues, Coleman, as well as

adopting the jay’s name, also imitated the song of a bird on his harp to

telling effect on his "Man

Trouble Blues” in August, 1927.

Burl

Coleman, born in 1896 in Gainsville, Alabama, used the name of a common bird in

the South, for his pseudonym as a blues man. As did pianist, Thomas Jones, who

recorded simply as “Jaybird” in 1928 when he

accompanied “Keghouse” for 10 sides, He also recorded for Library of

Congress in 1941 and 1942. Jaybird Coleman recorded a remarkable series of

vocal/harmonica blues in 1927 - 193O, closely related to the archaic field

holler which goes back to the beginning of the Blues, Coleman, as well as

adopting the jay’s name, also imitated the song of a bird on his harp to

telling effect on his "Man

Trouble Blues” in August, 1927.

Jaybird

Coleman c. 1917

Another bird common in

Southern states, is the brightly coloured bluebird, and its song is recalled by

Winston Holmes when he cut a vocal duet with the “Kansas City Butter Ball”,

otherwise Lottie Beaman. Holmes, a music promoter and tap dancer from Kansas

City Mobile apart from yodelling and his ‘bird effects’, also put in his own

vocal support when Lottie sang in mock seriousness:

“I

wish I had wings like an aeroplane, that flies in the heavens above.

I wish I had wings, like a little bird, I’d fly to that one that I

love.”(l0).

Drawing

on her contemporary environment as well as the natural one, Lottie Beaman also

sang some fine ‘regular’ blues such as “Going Away Blues” and “Rolling

Log Blues”, with some excellent guitar by Miles Pruitt. Winston Holmes was

also the owner of the Merritt record label, being one of the very few

black-owned labels in the 1920s and ‘30s. He had a zany sense of humour and

his handful of recordings with 12-string guitarist, Charlie Turner, in 1929,

reveal an otherwise undocumented facet of early blues and black music generally.

He may well have had some experience on the minstrel medicine show circuit,

which was still popular in the South during this period. Holmes imitated the

‘songbird’ at this session, on his “Rounders Lament” ,using the same

bird effects!, Backed up by superb bottleneck guitar from Charlie Turner.

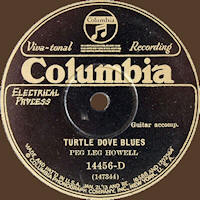

Lottie Beaman’s verse seems

to be an update of an older one which Georgia guitarist, Peg Leg Howell used on

his “Turtle Dove Blues”. Sang Howell:

Lottie Beaman’s verse seems

to be an update of an older one which Georgia guitarist, Peg Leg Howell used on

his “Turtle Dove Blues”. Sang Howell:

“If I had

wings like Noah’s turtle dove.(x3)

I would rise an’ fly, light on the

one I love.”(11).

Following his poetic opening line:

“I weep like a willow, moan

like a dove.” (12).

Recalled

by Blind Boy Fuller on his beautiful “Weeping Willow” recorded nearly a

decade later, for A.R.C. Peg Leg Howell was born in 1888 in Eatonton, Ga. and

was “rightly acknowledged as an important country blues singer in the Georgia

tradition.”(13). But as Oliver rightly says, Howell’s repertoire included

songs that pre-date the Blues, going back into

the l9th. Century.

Recalled

by Blind Boy Fuller on his beautiful “Weeping Willow” recorded nearly a

decade later, for A.R.C. Peg Leg Howell was born in 1888 in Eatonton, Ga. and

was “rightly acknowledged as an important country blues singer in the Georgia

tradition.”(13). But as Oliver rightly says, Howell’s repertoire included

songs that pre-date the Blues, going back into

the l9th. Century.

Peg Leg Howell c.

1926

“Many of

Howell’s blues verses dated back to the earliest stanzas noted by collectors:

verses....in “Turtle

Dove Blues” were noted by John A. Lomax in 1908 when tie collected them from

the Mississippi levee woman Dink as she was washing for the levee workers on the

Brazos River in Texas.”(14). A younger Georgia singer playing a 12-string guitar,

Barbecue Bob, used the ‘turtle dove’ phrase as an endearment for his

prospective lover:

“Can’t you near me

beggin’,

beggin’ for somebody’s love? (x2)

Tell me, can I get it, won’t

you be my turtle dove?”(15).

From Georgia to Missouri and

the fine, St. Louis-based singer, Luella Miller who used the traditional “If I

had wings” verse on her’ low-down moan “Walnut Street Blues” where the

“Blues passed her door”, backed by possibly Elmore Booker on some inventive

piano. As Oliver said in his sleeve notes “On this (“Walnut St. Blues”)

the piano was particularly adept, imitating a bird’s flight...”(16), as well

as a freight train stopping, in the ‘following verse. In a more lightweight

vaudeville—blues style, Marie Grinter sang more unusual “mourning dove”

verses:

“Early in the mornin’,

I rise like a mourn in’ dove. (x2)

Sobbin’ an’ singin’ about the man

I love.”(17)

Grinter ended her blues with

these lines:

“Mournin’ Dove Blues

is a woman is hard to please. (x2)

Mournin’ Dove Blues will make you tremble

in your knees.” (18)

Some 11 years later, U.S. Decca

got a prisoner out on parole so they could record him. A tough two-fisted

pianist, possibly from Texas, the singer called himself “Jesse James” and

for the traditional bawdy tune “Sweet Patunia”, he used lyrics to capture

some of the “shocking” atmosphere of this song, without upsetting the record

company censor. To this end, he incorporated some of Peg Leg Howell’s lines

with a mildly disgusting image of his own!,

“Now wake up mama, wake up

an’ don’t sleep so sound;

Give me what you promised me, before you lay it down.

I’m gon’ git my ‘tuni, only thing I love;

Make you weep like a willow,

sling snot like a turkle (sic) dove" (19)

It didn’t work; Decca

didn’t issue the title, and returned “James” back to jail! But the Peg Leg

Howell version, with its Old Testament overtones, persisted into the 195Os,at

least. Famous R’nB singer/pianist, Fats Domino, elaborated on the religious

vein in “The Prisoner’s Song” for Imperial records. As I recall, Fats

sang:

“If I had the wings of an

angel, over these prison wails I’d fly;

Straight to the arms of my loved one, an’ there I’d be willing to

die.”(2O)

The New Orleans piano man was

perpetuating part of an oral tradition that went back to the medicine/minstrel

shows of the l9th. Century.

Another song, recorded a few

months earlier than Howell’s “Turtle Dove Blues” was “Green Grass” and

with its “Green Grow The Rushes 0” structure, would have fitted just right

on a medicine show of the 1880s. Accompanied by ”Georgia Tom” Dorsey on

jaunty piano, Stovepipe Johnson appears to be parodying white minstrelsy and

country music as well. Commencing with “the hole in the ground an’ green

grass grows all round”, Johnson punctuates each new line with a pseudo

falsetto-cum-yodel; here underlined:

“now in that egg there

was a little bird,

Prettiest little bird, that ever did see.

Oh!, The bird in the egg,

An’ the egg in the nest,

An’ the nest on the branch,

An’ the branch on the limb,

An’ the tree in the hole,

An’ the hole in the ground,

Green grass grows all round, an’ round.

Oh!, the green grass grow.. all round.”(21)

This was, as I’ve implied,

more in the medicine show/hokum blues genre. But birds and birds’ nests

occurred in the heavy Delta blues as well; as Charlie Patton relates to the

pulsating, guitar-slapping rhythm that he and Willie Brown were putting down in

1930:

“Come on mama, come to the

edge of town;

Come on mama, go to the edge of town.

I Know where there’s a bird’s nest, built down on the ground.”

“If I was a bird, mama,

If I was a bird, mama, I would find a nest in the

heart of town;

Spoken: ”Lord, you know I’d build it

in the heart of town.!’

So when the town get lonesome. I’d be bird nest bound.”(22)

Patton was to re-record this

no. as “Revenue Man Blues” in 1934,without Brown, and still seemed to

generate the same kind of intense, driving beat!, “Bird Nest Bound” might

have been inspired by a 1926 record by Ardell “Shelly” Bragg (a female

singer), ”Bird Nest Blues”, or more likely part 4 of Jim Jackson’s big hit

“Jim Jackson’s Kansas City Blues”, which included the lines:

“I wish I’se a jaybird

flyin’ in the air,

I’d build my nest, in some of you high brown’s hair.”

Refrain:” An’ I’d move to Kansas City etc.(23)

Copyright © 2000 Max Haymes. All Rights Reserved.

__________________________________________________________________________

References

1. R. F. Patterson (Ed.).

“The Cambridge English Dictionary”. Tophi Books. 1990. P332.

2. Paul Oliver. Quoted in

“Story Of The Blues”. Barrie & Rockliff, The Cresset Press

3. Patterson. Ibid. p.412.

4.

Samuel Charters. “The Bluesmen”. Oak Pub. 1967. p.191.

5. Freeman Hubbard. “Encyclopedia

of North American Railroading”. McGraw-Hill Book Co. 1981. p.354.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8.

“Kassie Jones—Part 1”. Furry Lewis vo. gtr. 28/8/28. Memphis, Tenn.

9. Paul Oliver. Notes to

“Alabama Harmonica Kings 1927—30” L.P. Wolf WSE 127. c.1985.

1O.”LostLover Blues”.

Lottie Beaman vo., speech; Winston -Holmes vo., bird effects, yodelling; prob. Miles

Pruitt gtr. 21/8/28. Richmond, Ind.

11.”Turtle Dove Blues”. Peg

Leg Howell vo. gtr. 30/10/28. Atlanta, Ga.

12

Ibid.

13.Paul Oliver. “Songsters

& Saints”. Cambridge U. Press. 1984. p.257.

14.Ibid. p.19.

15.”Beggin’ For Love”.

Barbecue Bob vo. gtr., speech. 27/10/28 Atlanta, Ga.

16.Paul Oliver. Notes to

“Lottie Beaman 1924/26 and Luella Miller 1928”. L.P. Wolf WSE 124. c.1986.

17 . “Morning Dove Blues”

(sic). Marie Grinter vo.;unk. cit.; alt.;vln.;pno. 6/4/25. Richmond, In d.

18.Ibid.

19.“Sweet

Patuni”. Jesse James vo. pno. 3/6/36. Chicago, Ill.

20.“Prisoner’ s (Love)

Song”.

Fats Domino vo.

pno.;acc. by

His Band:

including Herb Hardesty or Lee Allenten.;Roy

Montrell

gtr. c.1958. 21.”Green Grass”. Stovepipe Johnson

vo. ;Georgia Tom pno. 26/ 7/28. Chicago,Ill.

22.”Bird Nest Bound”.

Charlie

Patton vo.gtr.,

speech; Willie

Brown

gtr. c.28/5/30. Grafton

Wis.

23.”Jim

Jackson’s Kansas City Blues—Part 4”. Jim Jackson vo gtr. 22/1/28. Chicago,

Ill.