Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Mule, Get Up In The Alley |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the mid-1870s the Rev. J.G. Wood - an avid purveyor of natural history - as well as a preacher of the Jewish faith, noted (with some surprise?) that “There are several references to the MULE in the Holy Scriptures, but it is remarkable that the animal is not mentioned at all until the time of David, and that in the New Testament the name does not occur at all.” (1) The main aim of this article is to highlight the importance of the mule and its relevance to the Blues singer. In his apparently unique tome (over 700 pages) Scripture Natural History Illustrated, Wood goes some way to answering his question, unintentionally! Part of which lies in his statement that “the mixed breed between the horse and the ass has been employed in many countries from very ancient times is a familiar fact”. (2) Although admitting that the origin of the mule remains unknown, Rev. Wood sees the ass, in its original state, as part of the reason for the mule’s temperament. This refers to the wild ass as opposed to the domesticated animal.

There then follows a ‘braying solo’ with some relevant spoken asides.

The almost reverential attitude depicted by Billiken Johnson was apparently widespread in rural black communities across the South in the early 20th. Century. “Blacks knew their mules so well that whites often felt they had a special gift to read the mule’s thoughts” .(5) In the case of a sharecropper from Alabama, ‘Nate Shaw’ (real name Ned Cobb) born 1886, he told his biographer that “Them mules aint goin to eat no more than they want. Just give em a good feed, plenty … Feed em three times a day just like I et - them animals, my mules or my horses, I considered the next things to my family.” [sic] (6) Yet generally speaking a mule only did what she/he wanted to do. Like the camel, the jack and jennet [Footnote 4: Male and female mule. ‘Jennet’ was usually abbreviated to ‘jenny’. See its use in a verse by Big Bill Broonzy in 1941 on his Feel So Good. The term seems to be derived from a name for “A small Spanish horse”. (7) ] knew the limitations of the weight they would carry. Very intelligent animals and rated by famous Mississippi writer, William Faulkner, “… second only to rats in intelligence …The mule I rate second. But second only because you can make him work for you”. (8) This stubborn streak (more later) is reflected on by Julius Daniels from South Carolina, in 1927.

But his interviewer, in the early 1980s, sheds some light on this term. It“ probably comes - not surprisingly in this heavily Viking-settled part of England - from Old Norse ‘horfa’, meaning ‘turn’”. (13) And “it is said of an obstinate or single-minded person that they ‘will neither gee nor ‘harve’” (14) according to ‘George’ and Bill Denby, another ‘horse chap’, from Yorkshire. A form of this became part of a floating verse in the early blues “What do you want with a woman she won’t gee nor haw?”. . In 1940, a version appeared on a typical hard hitting Tommy McClennan side It’s Hard To Be Lonesome [Bluebird BB B8669].

Following the advice of ‘Nate Shaw’ the great Blind Lemon Jefferson sings of a ‘balky’ [Footnote 5: Taken from the noun ‘balk’ there is no listing for an adjective such as Blind Lemon uses. The dictionary identifies ‘balk’ as “a barrier; a disappointment.” (16). Under the heading of the latter, a thesaurus includes the adjective “disgruntled” (17). But see Barrelhouse Words, p.10. Re “Balk”. Stephen Calt. [University of Illinois. Urbana & Chicago.] 2009.] mule which he likens to his girl friend or ‘crow jane’. The requested bag would contain corn-part of the mule’s staple diet.

This stubborn and ‘rebellious’ streak in mules can be traced back to ancient times and the wild ass. There were two distinct breeds: Asinus hemippus (wild ass) and Asinus vulgaris (the domesticated ass). [23] Originating from the continents of Asia and Africa, it appears that only the former (from ‘the East’) was the wild ass to be domesticated. But this was found to be a long process with very limited results. Even when the wild ass is “captured very young, can scarcely ever be brought to bear a burden or draw a vehicle. Attempts have often been made to domesticate the young that have been born in captivity, but with very slight success, the wild nature of the animal constantly breaking out, even when it appears to have become moderately tractable”. (24) Or in other words has seemingly become docile. This would appear to echo the approach of slave holders towards the first larger groups of Africans to be enslaved in Britain’s American colonies in the later seventeenth Century. [Footnote 6: See the ground-breaking book ‘Dreams Of Africa In Alabama (The slave ship Clotilda and the story of the last Africans brought to America)’. Sylviane A. Diouf. [O.U.P. New York] 1997. Especially p.p.95-98 re humiliation-psychological methods as well as physical- inflicted on these Africans who were from various far-flung regions in W.Africa and had no common language except a rudimentary style of ‘pidgin’ English; certainly within their first year of enslavement in Mobile, Alabama.]

Even the wild ass who was domesticated would sometimes revert

to its original untamed nature. In Palestine in the 1870s, an ass that “is

disobedient and strays from its master”

(25)

gets an ear clipped or nicked each time it happens. “Any Ass, no matter how

handsome

it may be, that has many of those clips. is always

rejected by experienced travelers, as it is sure to be a dull as well as a

disobedient beast”. (26)

Wood probably meant ‘sullen’ or ‘truculent’ rather than the popular concept we

have of ‘dull’ in the 21st. Century. The indomitable spirit of the wild ass, inherent in the mule and particularly the jack-also known as a ‘jackass’ - was reflected in the early African slaves and subsequently passed on to indigenous generations and later freedmen. Within two or three decades the very first Blues singers, like the young wild ass, featured ‘breaking out’ in varying degrees via their lyrics.

[Footnote 7: The ‘Winchester 73’ was claimed as the “fighting rifle of the old civilian West”. (30) This weapon was capable of holding 15 bullets in its magazine and was of “.44 caliber, in three styles” .(31) Made until 1898 when the Winchester company’s “famous Model 94” (32) superseded it. The following year of 1895 saw the introduction of “nickel-steel barrels, making possible use of smokeless powder”. (33) No doubt it was a model of this rifle Josie Miles took ‘down off the shelf’. Ex-slave Andy Brice told his interviewer (1934-1941) how he prepared to face white intimidation at the polling station to stop him voting on election day “at Woodward, South Carolina, in 1878,” (34) Brice stated “us got twenty sixteen-shooters” (35) and the author’s footnote ran: “Repeating rifles that carry sixteen bullets”. (36) Maybe Andy Brice (and the author?) was referring to one of the ‘three styles’ of Winchester 73 noted by Foster-Harris above.]

Josie Miles’ hard, flat and nearly toneless vocal bringing an awful realism to her words. Reflecting perhaps, a barely controlled and implacable hatred for ‘everybody’ who has done her and her fellow African Americans so many wrongs for such a protracted period of time since the 17th. Century, when enslavement of blacks became the order of the day in the American colonies. For ‘everybody’ one could read ‘the total white population’. Invoking sentiments that the rebellious preacher Nat Turner would have readily identified with during his bloody and “most violent of the rebellions” (37) during August, 1831. “Turners’ rebels had killed almost 60 white men, women, and children.” (38) before being captured and executed.

While in 1930, a driving Birmingham Jug Band cut Kicking Mule Blues [OKeh 8866] with an unidentified raucous singer who’s essentially single-liners give a definite pre-blues feel to this performance.

The ‘quiet’ characteristic of the domesticated ass, designated by Rev. Wood in 1875, does not seem to have been passed on to the mule in the South. Referring back to the nineteen-teens and twenties in Alabama, Nate Shaw recalled why a mule would often make its presence felt by emitting a loud ‘holler’ or ‘squall’. As he said: “There’s two causes for a animal squallin - he needs feedin or he’s missin’ his mate” [sic] (45) He went on: “My mules was used to eatin at dinner times, used to eatin every feedin time - mornin, dinner and night…Them mules looked to see me, bout twelve o’clock and I hadn’t feed em---‘agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh’--- I’d look around and they standin lookin right at me with their heads up---‘agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh-agh’---Sometimes they’d bray, squall out, ‘Eeeeeeee-eeeeeeeeaaaaaaaaaawww,hagh-ah-hagh-ah-hagh-ah-hagh-ah-hagh-ah-hagh-ah’ That animal needs feedin.” [sic]. (46) Before the advent of the steamboat whistle (c. early 1840s), one of the loudest sounds on the southern landscape was the unmistakable call of the mule. The Blues singer included it, with typical symbolic fashion in his/her songs and especially the sound of a mountain mule. [Footnote 8: “Mules were classed according size and were sold for a variety of uses. Their major classes were (1) sugar mules (for southern sugar plantations), (2) rice and cotton mules, (3) levee mules (for Mississippi River levee work), (4) mine mules, (5) railroad mules, and (6) mountaineer pack mules” ] In 1926 one of the earliest references on record was cut by the ‘Mother of the Blues’, Ma Rainey.

This was covered by the fine Texas pianist Pinetop

Burks in 1937 and variations of this stanza appeared in blues recorded

by Curley Weaver (Sweet Petunia). Big Bill Broonzy (Mountain

Blues), and Frank Brasswell (Mountain Girl Blues), in 1928,

1935, and 1930, respectively. It is undoubtedly the case that many

other examples exist in the annals of the early blues.

[Footnote 9: Similar titles such as Mountain Top Blues (1924) by

Bessie Smith; Mountain Blues by Washboard Sam; and

Mountain Baby

Blues by Monkey Joe

Coleman; contain no references to the mule.] Another aspect of the mule noted by the Blues singer was the colour of its coat; in particular the white mule. Once again, stretching back into antiquity, Rev. Wood reported that “White asses were selected for persons of high rank especially for those who exercised the office of judges. See Judges v.10: ‘Speak, ye that rode on white asses, ye that sit in judgement, and walk by the way’. Such Asses are still in use for similar purposes, and are bred expressly for the use of persons of rank. They are larger, and are thought to be swifter than the ordinary breeds;” (51) Wood observed that though the sight of an important government official or a judge riding an ass (aka ‘donkey’) in England would be strange indeed, (in 1875): “Both sexes used the Ass for riding, as they do now in the East.”. (52) As he says elsewhere, (in his day) the ass “is the universal saddle-animal of the East.”. (53) While the breeding of white asses may have vanished, the white mule was very much in evidence in the early 20th. Century in the South.

It seems that Blind Lemon Jefferson is singing about a pair of mules - especially as a male and female are also known as a ‘horse-mule’ and a ‘mare’, respectively. Not only used extensively for farming work, hauling lumber, etc. the mule is also employed as a popular form of transportation for many rural blacks. Back in the 1850s, ex-slave Robert Shepherd recalled for his white interviewer much later, that when a slave died on another plantation, “Marster would say: ‘Take de mules and wagons and go; but mind you take good care of dem mules’.” (58) Shepherd explained: “Dere weren’t many folks sick dem days, especially amongst de slaves. When one did die, folks would go twelve or fifteen miles to de buryin’.” .(59) [Footnote 11: Maybe more healthy in Kentucky where Robert Shepherd was enslaved and as pointed out elsewhere due to all food being cooked with no additives or ‘poisons’ (chemicals) and truly organic, contributed greatly to the health of the slaves. As well as so much fresh air and compulsory physical exercise! But further south in the malarial and snake-infested rice plantations, in Georgia and South Carolina for example, it was quite a different story. Although in 1937 another ex-slave, Julia Brown, concurs with Shepherd even though she was enslaved in Georgia, near Commerce. “We didn’t need many doctors then for we didn’t have so much sickness in them days, [end of 1850s to the early 1860s] and naturally they didn’t die so fast. Folks lived a long time then” .(60) (and see p.p. 22-23 Ibid; for detailed account of herbal remedies, daily diet, and methods of cooking, etc. ) Commerce lies some 60 miles north ]

So Lemon could be hitching a couple of mules to a wagon to go in search of his woman or ‘good gal’.

The very high esteem reserved for the mule by blacks since at least the beginning of the 20th. Century would naturally include the older animal or white mule. Indeed, with the advent of Prohibition in 1920, one of the most well-known moonshine concoctions (in the Blues) was dubbed ‘White Mule’. Presumably this potent liquor brought out the ‘wild and rebellious’ nature of the drinker. In 1929, sometime-record company boss and comedic singer Winston Holmes got together with the superb 12-string guitarist Charlie Turner to cut an incisive two-part ‘religious’ parody entitled The Death Of Holme’s Mule [ Paramount 12793]. As Paul Oliver graphically described they incorporated the much loved multi-layer construct of many early blues (63) in their mainly spoken dialogue:

[Footnote 12: Paul Oliver hears “one

of them long Moody numbers”. (64) But see his comments

on earlier hymns re ‘hark from the tomb’, etc.]

Referring back to the mule as an animal, Holmes describes how it protected him from the evil hoodoo spell of an “old lady” and chased her into the river!

Like Nate Shaw, who was once accused by a religious white man of worshipping all his property including his mules, (69) Winston Holmes seems to adapt this holy attitude. Or at least he is deriding it. He then sings in quasi-reverential tones:

Neither was a mule’s funeral just recorded fiction. In 1956 Nate Shaw bought a mule which became one of his favourites and he named her Kizzie. He kept her for sixteen years then finally sold her to some black neighbours/relations: the McCaffrey brothers. He told them “ ‘Take care of her. You see the shape she’s in. I’d hate to see her go down’. And every time Josie [his second wife] sees em -she goes over by Teak’s Church on the same road where they keeps that mule - she bones em about Kizzie and they tell her, ‘When that mule dies we goin to have Nate come over here and preach her funeral’.” [sic] (71) And in the late 1880s in Natchez, Mississippi “When Rumble and Wensel’s 30-year-old ‘Old Rock’ died, an obituary appeared in the local paper”. (72) In 1929, the same year that Holmes and Turner cut their recording; another parody on the same subject was made by blues singers John Byrd and presumably Mae Glover: That White Mule Of Sin [Champion 15816]. Masquerading as ‘Reverend George Jones’ and ‘Sister Jones’ they commence with some traditional gospel verses before the ‘preacher’ opens his sermon with comments and moaning from the sister and unknown male in the ‘congregation’. Parody it may have been but John Byrd, who only plays guitar in the introduction, comes across as a very ‘authentic’ preacher extending the mule symbolism present in the Holmes and Turner opus; with regard to White Mule illegal liquor.

Sister Jones’ ‘prayer’ relating back to the antebellum song You Shall Be Free (74) and recorded famously by the Beale Street Sheiks as You Shall [Paramount 12518] in 1927. This title and the next one from their first session (It’s A Good Thing) were “re-made on matrices 20043/44 … and both versions of each title were issued.” (75) about a month later. To many African American farmers, as well as blues singers, the relationship with their mules could be a type of the ‘love-hate’ variety. Even if they could often read the mules’ thoughts, as Bill Ferris has stated. On the one hand the mule could be bestowed with supernatural powers as implied by Big Bill Broonzy, and the animal could just take the whole planet away! At least that’s the way it seems on his Plow Hand Blues [Vocalion 05452]. (and see Appendix I)

Although as Paul Oliver notes Williams is not so pointed or incisive as verses collected earlier in the field. (Footnote 16: See Songsters & Saints. Paul Oliver. Ibid. p.p. 104-106. for more detailed discussion re lyrics of Go ‘Long Mule and some traditional verses). However, in some of his spoken comments Ukulele Bob Williams is certainly more frank.

But a field recording made in 1936 by Library of Congress featuring Willie Williams, (no relation) makes no bones about it and threatens his team of mules with violence culminating in possible death in HIS comments, weaving between his stunning ‘work-song holler’; punctuated with ‘pops’ of his muleskinner’s ‘line’ (i.e. a whip).

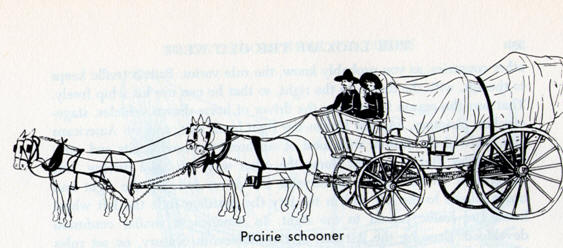

Supporting Paul Oliver’s comments above, the Lomaxes - who recorded Willie Williams in a “bare room” in the state penitentiary, at Richmond, Virginia - called his performance one of the “hollerin’ songs”. This genre, usually referred to as ‘field hollers’, is a cornerstone of the roots of the Blues. These songs are “sung with an open throat - shouted, howled, growled, or moaned in such a fashion that they will fill a stretch of country, satisfy the wild and lonely and brooding spirit of the worker. (81) Although, some 7 years after recording this song by Willie Williams, B.A. Botkin and Alan Lomax stated “The final stanza is pervaded with the feeling of the heroic common to all laborers”; (82) they give no explanation as to the references in this verse - or stanza. Probably because they didn’t know the actual sense of the words, and hadn’t asked Williams about that sense. I certainly was puzzled for a long time until very recently trawling through one of the books in my library about the ‘old West’. This tome devoted about half-a-dozen pages to early animal-hauled transportation, from the famous and large Conestoga wagon (often circled by ‘Indians’ in old cowboy movies) on down... In the earlier 19th. Century these cumbersome vehicles had oxen, horses, or mules for their motivation. Due to the often atrocious ‘roads’ at that time, a team of oxen were generally preferred. But with the coming of at least some improvements in the shape of early highways and gravel/dirt roads, (Footnote 17: See When The Moon Creep over The Mountain (Highways in the Early Blues - From Dirt Roads to Highway 61) - Part 1. Max Haymes. Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No.2. p.p.157-164. Frog Records Limited. 2011. Paul Swinton (Contributing Ed.) a smaller (but still large) wagon appeared known as a Prairie Schooner. Now, horses and mules - faster than oxen -became more popular. As Foster-Harris said, the Prairie Schooner was still “decidedly top-heavy, clumsy, and hard to handle in anything like broken country. But it was widely used”. (83) It is quite likely, Willie Williams had a Prairie Schooner in mind when he claimed to have a ‘high-board wheeler’ alluding to the high wooden sides of the wagon (see pic.). While the rear or ‘hind wheels’ are described as being “5 feet, 10 inches, the front ones a foot less in diameter”. (84) And “these enormous wheels had tires 6 inches wide and an inch thick”. (85) It is quite possible of course that the wagon in William’s song was a smaller vehicle than the Prairie Schooner, but still comparatively high-sided; also with high/big wheels.

At this point, a little more preamble from Foster-Harris is illustrative as to the term ‘high roller’ which could well refer to the mule itself - or at least a certain team of mules. Consisting of a minimum of two, a team in the old Conestoga days would often have six animals, in pairs, to haul their heavier loads. “The front team was called the lead team, the middle one the swing team, and the rear one the wheel team”. (86) Generally, in the South, by the late 19th. Century, the swing team was omitted and 4 mules were more the norm for larger loads. Referring to the wheel team, Foster-Harris relates: “Since only this team could exert power to back or brake the wagon, these usually were the sturdiest horses in the outfit”.(87) The same applied to a mule team, of course. The ‘wheel mule’ easily corrupting to a ‘wheeler’, and ‘high’ and ‘big’ were interchangeable in their meaning as far as the muleskinner was concerned. This leads on to the other puzzling term in William’s song, ‘a western tongue’. The wheel team had “backing straps attached to their harness, heavy wide horizontal pieces across their buttocks, against which they could throw their weight to help slow or stop the wagon”. (88) And “the wagon tongue was rigidly attached to the axle;…So by turning the wheel team, the driver could turn the wagon tongue, which in turn, steered the front wheels and so the wagon”.(89) The wagon tongue was a “heavy pole which extended between them [the mules] from the front of the wagon up to about even with their noses.”, (90) or as he says elsewhere, it was “another huge timber that fastened directly to the center of the axle, extending back to the end of the bed [in the wagon] and projecting some 12 feet in front of it”. (91) [see pic.] Also “the long tongue kept the vehicle from tipping over”. (92) The ‘western’ part of Willie William’s phrase harks back to times when states such as Mississippi and Missouri were part of the old West and indicated the ‘new’ (at the time) ever-growing western frontier. His ‘gonna stick it in the bottom’ line refers back to the Botkins & Lomax ‘heroic’. Williams is going to turn that wagon tongue and cross the muddy river bottom lands (Footnote 18: For more detailed description of the river bottoms, see Railroadin’ Some Ibid. p.p.96-99.) no matter what - even ‘if it breaks my arm’. As these writers noted: “The holler is a musical platform from which the singer can freely state his individual woes, satirize enemies, and talk about his woman”. (93) The muleskinner could also admire a hero who was hated by the white population; even if indirectly. Willie Williams seems to refer to a four-mule team on his recording and they have names such as Jerry, Pearl, Rhoady, and Dempsey. The first two are ‘harmless’ (but see Appendix II) enough as so is ‘Rhoady’, drawing on an earlier black plantation figure of ‘Aunt Rhody’ which is easily corrupted in song to ‘Rosie’; a notorious prostitute who visited southern black prisoners posing as a ‘wife’ of one of the inmates. But with ‘Dempsey’ the picture becomes a little murkier. This could well refer to a white heavyweight boxing champion from the nineteen-teens: Jack Dempsey. Along with several other famous white boxers, Dempsey refused to go in the ring with the world heavyweight champion of the times - Jack Johnson; who was the first black to hold this title. (Footnote 19: See the definitive book on Jack Johnson: Unforgivable Blackness -The Rise And Fall Of Jack Johnson. Geoffrey C. Ward. [Pimlico. London] 2005. Rep. 1st. pub. 2004.) Using the race card but naturally accused by blacks (not without good reason) of being frightened of Johnson, Jack Dempsey is reduced to a mule who Willie Williams threatens to kill if he doesn’t obey him. Indeed, one of his verses was probably inspired by Julius Daniels on a 1927 record Ninety Nine Year Blues [Victor 20658].

Invoking Josie Miles and her Mad Mama Blues from three years earlier (see just below Footnote 7 above). That the rebellious nature of the ancient wild ass passed on to the mule is readily apparent in Daniel’s words. Like Ms. Miles he is mainly aiming his anger at white people in general. Yet even he did not make any reference to Jack Johnson, and neither did any early blues singer - at least not on a record. Unlike Joe Louis ‘the Brown Bomber’ who kept a low profile in the ‘30s when he was not fighting in the ring, who WAS eulogized on several blues recordings; Johnson actively flaunted his superior prowess as a world heavyweight champion and married or had relationships with white women and paraded the fact quite openly. (95) The latter appeared as a racial threat to the whites in a way the well-mannered Louis did not. In 1930, the self-styled ‘High Sheriff from Hell’ and the ‘Devil’s Son-in-Law’ Peetie Wheatstraw felt he had to ‘downgrade’ the apocalyptic atmosphere of Josie Miles and Julius Daniels.

The shotgun seemed to be a spin-off of the Winchester rifle favoured by Ms. Miles and as the thirties progressed appeared in some blues as a species of floating verse. As superb slide guitarist Oscar Woods ‘The Lone Wolf’ turns his anger on the woman he loves who has now left him.

Ultimately, the devil who is so closely linked to the early blues - ‘the devil’s music’ – via recordings by Skip James, King Solomon Hill and Robert Johnson, et al., is also connected perhaps unsurprisingly to the ancestor of the Southern mule: the wild ass. Rev. Wood gives an example of one legend concerning the ass and the devil. This is an “old Rabbinical legend reflecting the Flood and the admission of the creatures into the ark. It appears that no being could enter the ark unless specially invited to do so by Noah. Now when the Flood came, and overwhelmed the world, the devil, who was at that time wandering upon the earth, saw that he was about to be cut off from contact from mankind, and that his dominion would be forever gone. The ark being at last completed and the beasts called to enter it, in their proper order, the turn of the Ass came in due course. Unfortunately for the welfare of mankind, the Ass was taken with a fit of obstinacy, and refused to enter the vessel according to orders. After wasting much time over the obstinate animal, Noah at last lost patience, and struck the Ass sharply, crying at the same time ‘Enter, thou devil!’. Of course the invitation was at once accepted, the devil entered the ark, and on the subsiding of the waters issued out to take his place in the newly begun world”. (98) The answer to this particular ancient problem seems remarkably akin to the one Nate Shaw faced in Alabama, much later in 1945, at the foot of the narrow bridge across the swamp with his balky mule. (see ref. 22 above) For ‘a fit of obstinacy’ one could read resilience and strong determination. Or as Rev. Wood put it “There are several passages of Scripture in which the Wild Ass is distinguished from the domesticated animal, and in all of them there is some reference made to its swiftness, its intractable nature, and love of freedom”. (99) By the time the mule was being utilized in the South, these characteristics would be a major influence on enslaved African Americans and freedmen alike. This also epitomizes the spirit of the Blues and goes a long way to explaining the reason why Southern blacks seemed to possess that ‘special gift to read the mules’ thoughts’ as American Blues author Bill Ferris referred to. (see ref 12 above) The general demeanor of earlier African American music - sacred and secular - is reported ‘wild and unaccountable’ in the words of famous English actress Fannie Kemble during her stay in Georgia in the earlier 19th. Century. The word ‘intractable’ has one definition which reads: “not to be governed or managed” (100) which perfectly describes the immortal phenomenon - the Blues. Conclusion The ‘lowly mule’ as I deemed it in my Introduction has turned out to be anything but lowly in the Southern diaspora - especially as far as the black farming community was concerned - and most importantly for this survey; the early Blues singer. This animal actually had the highest of ‘royal’ antecedents way down the line referring back to the domesticated wild ass in Biblical times. Rev. Wood quoting from the Old Testament, makes several references to princes, rulers, judges, and powerful ‘chief men’; who all rode an ass (Judges 10:3,4, & 12: 13,14.) as it was seen as the most significant symbol of power and transportation in those early times; as well as a token of wealth. One such chief is known across the globe, Abraham in the Book of Genesis. Described by Wood as “an exceptionally wealthy man, and a chief of high position, [he] made use of the Ass for the saddle. (Gen. xxii.3).” (101) And the obvious one being a king-Jesus-(Zecharia.9:9). Wood rightly concludes: “so far from the use of the Ass as a saddle animal being a mark of humility it ought to be viewed in precisely the opposite light”. (102) As he elaborates: “The fact is, there was no humility in the case, neither was the act [entry of Jerusalem by Jesus riding on an ass] so understood, by the people. He rode upon an Ass as any prince or ruler would have done who was engaged on a peaceful journey, the horse being reserved for war purposes. He rode an Ass, and not on the horse, because he was the Prince of Peace and not of war, as indeed is shown very clearly in the context”. (103) Whether a black sharecropper such as Nate Shaw was aware of this ‘aristocratic heritage’ which had passed on to his mules, he certainly could not have had more respect for them than he actually did. As he readily admitted they were up there with his wife and children in importance and quality of his life; hard and unrelenting as it may seem from a 21st. Century urban vantage point. But nevertheless, even as a Billiken Johnson might reflect this respect on his Wild Jack Blues, there were other singers who did not. Mississippi’s Sam Chatman quite cheerfully used the mule as part of the rich tapestry of sexual symbolism which coursed through the Blues. Although one of the famous Mississippi Sheiks string band, like most of his siblings he did not record with them. Indeed, the group usually consisted - on record - of superior fiddler Lonnie Chatman and singer/guitarist Walter Vinson, with occasional support from Bo Chatman; better known as a solo artist sporting the name Bo Carter. Sam Chatman is no longer so enamored of his wife or lover, inferring he can no longer satisfy her undiminished sexual demands, as he gets older; at the same time putting the blame on her!

Lonnie supplying a comic fiddle imitation of a braying mule which was also used by some old timey musicians on recordings in the 1920s. But there were also drivers or muleskinners who treated their teams in a more brutal fashion. Maybe, they ‘saw’ their unfortunate mules as surrogate mean white bosses, as Paul Oliver has suggested. In 1971, another Mississippi musician, in the cane fife and drum tradition, recalled an old work song/holler from earlier days. Othar Turner’s words sadly reflected a widespread practice of mis-treatment.

The singer’s long drawn-out moans harking back to the Lomax’s ‘hollerin’ songs’ (see ref. 93 above) as featured by Willie Williams, for example. The one major addition being the very skillful guitar phrases supplied by Lonnie Johnson, which interlace the archaic vocal with almost cunning dexterity. As pioneer Blues author Sam Charters put it, Alexander’s “style of singing, with its close relationship to the holler, enabled him to use the field songs almost without change... [together with] Lonnie Johnson, who developed a free guitar style to accompany the slow field chants, and their first duets were richly musical.” (108) But his resulting masterful accompaniment came at a price. As he told Paul Oliver many years later: “He was a very difficult singer to accompany; he was liable to jump a bar, or five bars, or anything. You just had to be a fast thinker to play for Texas Alexander. When you been out there with him you done nine days work in one! Believe me, brother, he was hard to play for.”. (109) But on balance, the majority of muleskinners treated their animals with respect. Although they had developed frightening skills with a tool of ‘guidance’ - the dreaded bullwhip. “Typically a bull whip had a short hickory handle, 2 feet long, a braided body from 12 feet to as much as 20 feet long, then finally a buckskin popper… An expert … could knock a fly off the ear of an ox [or mule] 20 feet away without bringing blood. (Footnote 22: A song called Mule Train which featured imitations of this hard cracking sound was popularized by the white US ballad singer Frankie Laine - amongst other hit versions including one by country man Tennessee Ernie Ford- in 1949 (107). A few years later on, as a young lad in the UK, I was part of an audience at some sort of local function which included a bald-headed man performing Mule Train with an aluminium /silver tea tray which he kept banging on the top of his head at the appropriate ‘whip-cracking’ moment. The effect was startling and only ended when the performer realized a trickle of blood was running down his face!) He could also cut the eyes out of a human opponent’s face or slash him to ribbons”. (110) Perhaps not quite as deadly but bloody all the same, were the bullwhipping skills of a certain ‘Captain Jack’ (white) who was overseer of a gang of black prisoners according to Mississippi’s Son House on his remake of a 1930 Paramount recording he did for the Library of Congress in 1942. This new version of County Farm Blues [matrix 6608-A-1(a)] included a necessarily limited protest about the ill-treatment suffered by black prisoners at the time, and perhaps was a sign of the times as House omitted any such scenario from his original recording in 1930.

But as far as his mules were concerned “… being valuable the … whip popper seldom actually injured his animals”. (112) However, Foster-Harris adds: “… his language notoriously was enough to scorch even a mule’s thick hide;” (113) Of course in reality it was the amount of venom and anger in the muleskinner’s tone of voice as well as the strength of his bullwhip which would finally motivate most obstinate animals.

As well as the artists in this text, the mule also featured in early blues by rural singers as varied as William Harris, Kokomo Arnold, Rabbit Brown, Otto Virgial; more urban performers like Casey Bill Weldon and Jazz Gillum; vaudeville blues artist Lizzie Miles; and the Hall Johnson Choir wearing their secular hat. Even a hokum singer ‘Blind Bogus’ Ben Covington would remember his roots and dropping his sobriquets recorded a recently discovered Muleskinner Moan from c.1928 accompanied by a fine but unidentified pianist. This can be considered an offshoot or precursor of the Willie Williams O Lord, Don’ ‘Low Me To Beat ‘Em he recorded for the Library of Congress in 1936. The mule was simply as much a part of their environment and life-style as the barrelhouse, cabaret, railroad, levee or the seemingly endless steamboat landings on the Mississippi, Red, Arkansas, Tombigbee or Ohio rivers and many other southern ‘streams’.

As well as being one of the main

factors in the Southern agriculture system prior to the 1950s. the mule assumed

other roles such as hauling trolleys through the city; these were the precursor

of the electric street cars around the turn of the 20th. Century.

Interestingly, it was generally the mule that was used for trolleys in the South

(see pic.) while the North preferred the horse. As well as being a mode of

transport carrying an individual as depicted in the Charley Patton ad.

(see above),

when harnessed to a small two-wheeled vehicle; blacks and whites could travel

several miles into the woods to attend a picnic.

As well as being the main source for hauling urban trolleys or street cars before the advent of the electrified version, the mule became identified with a far more powerful icon – the steam locomotive. The term for a horse mule (‘jackass’ or ‘jack’) was transferred to this new and awesome invention and became part of the well-used phrase ‘balling the jack’. (Footnote 23: See Railroadin’ Some. Ibid. p.37 for more details of this phrase.) Apart from appearing in some early blues lyrics in different titled songs, there was a lone entry in the canon which obviously featured the jack as the basis of the main theme. In 1937 the great St. Louis-based pianist Walter Davis cut his Big Jack Engine Blues [Bluebird B87325]. Adapting traditional verses to his own inimitable style and greatly enhanced by Henry Townsend’s facile guitar, Davis sings of going to the Piedmont area down south where he can see part of the Appalachian range - the Smoky Mountains - which are actually in Eastern USA; but ‘west’ is the obvious choice using poetic license in Davis’ lines.

There was even at least two particular locomotives which acquired the sobriquet ‘Old Maud’(e) which had mule connotations. Black oil cleaners in a roundhouse - which was where the engines were stored when not in use - would literally come up against this ‘railroad mule’. One was “America’s first articulated, or Mallet engine”, (115) completed for the Baltimore & Ohio RR. (B.&O) in 1904, some 20 years after it had been successfully designed by Anatole Mallet in France. (116) Stover describes this locomotive as a “giant 0-6-6-0 [wheel formation] … and had an impressive tractive power of 71,500 pounds”. (117) Qualities that would be much admired by the Blues singer. As Stover tells it: “The engine carried the number ‘2400’, but since it was often balky, it was frequently called ‘Old Maude’ [sic] after a comic strip mule of that day.”; (118) invoking the Blind Lemon Jefferson song (see ref. 18 above).

Interestingly, a recording was made in Atlanta when the Southerns’ Maud would till have been switching box cars, etc. in the freight yards. In 1928 Alec Johnson, an older singer, recorded his Sister Maud Mule [Columbia 14378] accompanied by Mississippi musicians Kansas and Charlie McCoy on guitar and mandolin respectively, Bo Carter (as ‘Bo Chatmon’) on fiddle, with a seldom-heard unknown piano player. The stubborn and fierce independence of spirit shown by ‘Sister Maud’ is akin to the anarchic character in Mad Mama Blues by Josie Miles. Johnson’s appellation ‘Sister’ pointing up the solidarity he felt with such a spirit. Is it a coincidence that this mule’s name has the same spelling as the Southern Railway’s switch engine?

Of course the ‘comic strip’ referred to, would have been even more accessible to Alec Johnson. Created by Frederick Burr Opper in 1904 - the same year the Mallet locomotive appeared on the tracks - it ran in the Sunday newspaper the New York Journal, for several years. (122) It’s usual title was And Her Name Was Maud along with other famous strips by the same author. And although “Maud was phased out in the 1910s , [she] reappeared [by public demand] from 1926 to the last appearance on October 14 1932.” (123) Markenstein’s description of Maud hits the nail on the head in regard to both her and the Blues singer. “Maud was a mule, but a mule with a real personality ---which included a stubborn streak that did credit to her species. What she liked to do best was get up on her front legs and deliver a resounding kick with her rear pair. She was generous with her kicks, and her very favorite target was Si Keeler, the farmer she belonged to. Or, rather, the one whose farm she lived on and whose hay she ate - it probably isn’t quite accurate to say she ‘belonged’ to anyone”. (124) It is the last sentence which so typifies the rebellious power of the Blues - and Maud’s ancestor the Wild Ass from Africa. Alec Johnson’s song is a classic example of the mule’s and the blues singer’s unshakeable psyche. He appears to be an older man as has already been said. Not just because of his vocals but also his style, and that of his younger musicians’ playing. Sister Maud Mule invokes the aura of minstrelsy and the medicine show. But there is a glimpse of an earlier time back in the immediate post-war years in the South. Johnson’s references to ‘the whole militia’ and ‘the colonel, too’ probably allude to the Yankee soldiers who soon after the Civil War monitored the Freedmens Bureaux set up by the Federal government to mobilize the Reconstruction period. “The greatest numbers of ex-slaves were cared for by Agents of the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands - commonly called the Freedmen’s Bureau. This agency of the War Department was created by Congress near the end of the War (March 3, 1865)”. (125)

Unlike Opper’s mule Maud, an un-named animal in real life is featured in a Memphis Minnie song from 1935 - Sylvester And His Mule Blues [Decca 7084].

Re-telling the case of a farmer who was hitting the bottom in survival stakes during the Great Depression, and was forced to sell his mule. In desperation he rings the White House in Washington and asks to speak to the President - Franklin D. Roosevelt. Initially Sylvester’s call is answered by a secretary before actually getting through to the President himself. Roosevelt assures him he will look into Sylvester’s case and indeed some help was forthcoming within the following few months by way of the distraught farmer getting access to a mortgage loan scheme (Footnote 24: See the definitive book on Roosevelt which includes a whole chapter on this incident: Roosevelt’s Blues (African American Blues And Gospel Songs On F.D.R.). Guido Van Rijn.[University Press of Mississippi. Jackson] 1997.) as part of the federal government policy. In 1934, the year previous to Minnie’s recording, the ever-popular Rev. J.M. Gates uses the Sylvester case while praising the greatness and fairness of FDR - “I mean he is a friend to everybody, both white and black. Both brown - everybody ... Look at Mississippi. Yonder on the river. A Negro with his mule”. (127) Gates gives his full name as Sylvester Harris but not before prompting from a female member of his congregation! Although Frederick Burr Opper’s And Her Name Was Maud was his own creation, it is undoubtedly true he must have been inspired in part by the tradition of folk tales that are rich seams in the bedrock of the South since the 17th. Century. Of course Sylvester’s mule would have become part of that tradition. One of the main and richest sources emanated from the slave community. Opper’s even more famous contemporary Joel Chandler Harris himself is a classic example with his ever-popular tales of Brer Rabbit and co. As a US author, John Blassingame, explains at some length. These folk tales were an essential core ‘tool’ for the slaves’ survival - both physically and spiritually in a secular way. These “are in many respects easier to analyse than spirituals or secular songs even though the systematic collection of them is more recent”. (128) Blassingame continues: “Primarily a means of entertainment, the tales also represented the distillation of folk wisdom and were used as an instructional device to teach young slaves how to survive.”. (129) But the slave did not live in perpetual denial of his everyday life. “While holding on to the reality of existence, the slave gave full play to his wish fulfillment in the tales, especially in those involving animals. Identifying with the frightened and helpless creatures, so similar in their relations to the larger animals to the relationship of the slave to the master, the slave storytellers showed how the weak could survive. Especially in the Brer Rabbit tales, the hero, whether trickster or braggart, always defeated them larger animals through cunning.” (130) By the time the Blues - it is usually agreed - had arrived in the 1880s and 90s, other animals appeared in the singers’ repertoire such as panthers, rattlesnakes, black spiders, boll weevils, bears, wolves, buzzards, and bumble bees; hardly of the ‘frightened and helpless’ variety. Of course these examples and others including the hyena, jaybird, etc. hark back to songs from West African cultures. Some were handed down in oral history via Haiti and voodoo beliefs. Birds were also invoked in the shaping of the Blues. Owls (often called ‘hoot-owls’) and the whippoorwill are part of the hoodoo/voodoo cult which is still relevant today and included by early singers in the Blues. Also the eagle, ‘turkle’ (turtle) dove, robin, and the beautiful blue bird; were all part of the environment that the first Blues performers found themselves in. (Footnote 25: See Birds And The Blues by Max Haymes. www.earlyblues.com). Along with the domesticated/farm animals, the mule became an important nucleus of inspiration for earlier rural black communities and especially the Blues singer. As Blassingame put it “By objectifying the conditions of his life in the folk tales, the slave was in a better position to cope with them. The depersonalization of these conditions did not, however, distract the slaves’ sense of the brutal reality of his life”. (131) The Blues singer is simply continuing and evolving these slave story tellers’ tales. A classic example appears in Casey Blues [Bluebird B6519] by Casey Bill Weldon in 1936, which also utilizes the mule symbolism. His woman has been gone for much longer than he expected and after a dream ‘clinches’ the matter, he admits the truth of the situation - his relationship is over - but does not consider he was any part of its cause.

It was not the fact of the Blues singer’s own personal failure which helped cause the break-up of a loving relationship. It was the ‘mean old train’ or its ‘cruel fireman’ and ‘low-down engineer’ which took their partner away from them. In his Hangman’s Blues [Paramount 12679 - matrix 20816-2], Blind Lemon Jefferson in the role of a condemned murderer clings to the vain hope that a hoodoo doctor can save him from his imminent hempen execution. (Footnote 26: See Railroadin’ Some. Ibid. Ch. 7 for Blind Lemon Jefferson’s denial of his lover’s death in Gone Dead On You Blues and also a small group of blues describing the partner leaving at the train station for the last time scenario where all blame for the break-up is placed on the railroad, and/or train crew, or the train /locomotive itself.)

But, oddly perhaps, despite the foregoing central importance of folk tales to the well-being of initially the enslaved blacks, then the freedmen, and subsequently the Blues singers in the 20th. Century; animals are included in the Brer Rabbit tales; only a couple of references are made to the mule by Joel Chandler Harris. Even these do not appear in the famous stories themselves but are featured in songs collected from blacks earlier in the 19th. Century. One of these was titled Corn Shucking Song and runs in part:

Which ever attitude a black worker adopted towards the mules under his care, be it in the fields, on a levee, digging a ditch or transporting on a steamboat, for example; he/she generally identified with the animals in a ‘oneness’ that could only develop over many years being in regular close proximity in a kind of two-way reciprocal process. After all, the mule depended and expected to be regularly fed, watered, and sheltered; at the very least. Also as an intelligent animal it must have felt some sort of ‘bonding’ especially towards a private owner on smaller and medium sized farms, certainly in the South. Sometimes the black worker seemed to resent the animal’s position as being far more secure in life than his own in his everyday existence in the South. Ex-slave, Thomas Cole, born “August 8, 1845”. (135) in Jackson County, Alabama, declared “Den, when a slave gets grown, he is jest lak a mule. He works for his grub and a few clothes and works jest as hard as a mule. Some of de slaves on de plantation ‘jinin’ our’n [next to ours] didn’t have as easy a time as de mules, for de mules was fed good, but de slaves lak ter have starved ter death; de marster jest gives dem nuf to eat ter keep dem alive.”. (136) This was taken from the Federal Writers Project between 1934 and 1941, linked to the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The latter appearing in several early blues singers’ recordings - including titles by Casey Bill Weldon and Peetie Wheatstraw. Thomas Cole’s resentment was still mainly directed at his mules rather than the white ‘marster’ of the plantation. But in 1930 one blues singer made no bones about the cause of his own mistreatment - the ‘boss’ or white contractor who ran the levee camp.

But although the South moved at a far more leisurely pace than other regions in the US, the scenario recalled by Gene Campbell was inevitably being replaced by more modern technology. The tractor which had been shunned by the majority of the white plantation owners while cheap labour, in the form of share cropping, was readily available; were gradually forced into a transition from a primarily mono-culture of ‘king cotton’ to a more widely embracing agricultural programme of diversification. By the late 1930s the tractor (already well-established in other regions) finally ‘arrived’ in the South, along with other innovations such as the mechanical cotton picker. “What kept the mule in the Delta was the fact that the mechanical cotton picker had not yet been perfected, though the mule had little to do with the actual harvest … After the war labor was slow in returning, and by then the mechanical picker had come on the market.(138) Along with other innovations such as the crop sprayer plane, the plantation owner had a “tractor with a flame cultivator to burn the weeds; the same driver [who operated the mechanical cotton picker] and tractor equipped with other specialized implements to cultivate the cotton, eradicate the grass, plant the seed, drill in the fertilizer, knock down the furrows, break the land. A tractor with a skilled driver could take the place of ten mules and ten men with their dependents.”. (139)

Yet to the Southern black farm worker this situation was seen as a threat to their annual income -which indeed it was. More machinery naturally meant less farm workers. So Sleepy John Estes echoed a popular if somewhat reactionary sentiment.

As has been illustrated at some length the mule was one of the major icons in the world of early blues singers. Apart from songs/artists already quoted the mule appears in blues by Skip James, William Harris, King David’s Jug Band, amongst many, many more. The blues singer, along with his forbears born in slavery, shared much the same work conditions and environment as the mule. Back in the antebellum period former slave John P. Parker recalled for his interviewer Frank Gregg (a white man) between 1886 and 1889, on his time in Alabama during the 1830s and ‘40s and how slaves “were sold south like their mules to clear away their [Alabama’s] forests.”; (141) preparing the land for the large cotton plantations yet to come. Indeed, the blues and the mule are too intertwined to be seen as separate entities. As master bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson employs some simple yet graphic poetry on his initial secular, and probably most awesome, recording in 1926: Well, the Blues come to Texas, lopin’ like a mule. (142)

‘Mississippi’ Max Haymes.

__________________________________________________________________________ Notes:

Illustrations:

Additions/Corrections &

Transcriptions by Max Haymes.

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is readily apparent that white mules would have been in

abundance given their longevity, often reaching 30 years or more and still

working. But oddly no blues refers to them. But I suppose a mule is a mule

whatever their colour. Except when their coats were black and grey as in Blind

Lemon’s Black Horse Blues.

It is readily apparent that white mules would have been in

abundance given their longevity, often reaching 30 years or more and still

working. But oddly no blues refers to them. But I suppose a mule is a mule

whatever their colour. Except when their coats were black and grey as in Blind

Lemon’s Black Horse Blues.

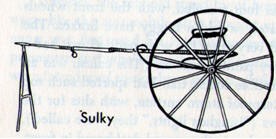

This was a light personal

buggy called a ‘Sulky’. These picnics were often larger affairs lasting a

couple of days and frequently featured black string bands for entertainment with

fiddle, guitar, banjo, or mandolin. Leadbelly would refer to these events as

‘sukey jumps’. (see

This was a light personal

buggy called a ‘Sulky’. These picnics were often larger affairs lasting a

couple of days and frequently featured black string bands for entertainment with

fiddle, guitar, banjo, or mandolin. Leadbelly would refer to these events as

‘sukey jumps’. (see