|

Chapter

II -

Silver Spades and Golden Chains

Perhaps

one of the most popular Blues artists before W.W.II, and certainly one

of the best remembered even 40 years after his death, was the rural

singer/guitarist from near Wortham, Texas - Blind Lemon Jefferson. First

recording at the

end of 1925, Lemon went on to cut nearly a hundred sides until his

premature death in Chicago during the winter of 1929-30. This large

repertoire included two versions of a song a-typical in blues, which

Jefferson called, "see That My Grave's Kept Clean" in 1927 and, "See

That My Grave Is Kept Clean" the following year. A-typical in so far as

the first line is repeated three times rather than twice which became

the almost standard format in the Blues: Perhaps

one of the most popular Blues artists before W.W.II, and certainly one

of the best remembered even 40 years after his death, was the rural

singer/guitarist from near Wortham, Texas - Blind Lemon Jefferson. First

recording at the

end of 1925, Lemon went on to cut nearly a hundred sides until his

premature death in Chicago during the winter of 1929-30. This large

repertoire included two versions of a song a-typical in blues, which

Jefferson called, "see That My Grave's Kept Clean" in 1927 and, "See

That My Grave Is Kept Clean" the following year. A-typical in so far as

the first line is repeated three times rather than twice which became

the almost standard format in the Blues:

| |

1. |

"Well it's one kind

favour, I'll ask of you, (x3)

See that my grave is kept clean."

|

| |

2. |

"It's a long lane

that never ends, (x3)

It's a sad wind that never change."

|

| |

3. |

"Well, it's two

white horses in a line, (x3)

Gonna take me to my buryin' ground."

|

| |

4. |

"When your heart

stops beatin' an' your hands get cold (x3)

It ain't long 'till your in (a) cypress grove."

|

| |

5. |

"Have you ever

heard a coffin sound? (x3)

Then you know the poor boy is in the ground."

|

| |

6. |

"You may dig my

grave with a silver spade, (x3)

You may let me down with a golden chain."

|

| |

7. |

"Have you ever

heard a church bell tone? (x3)

'Then you know that the poor boy is dead an' gone." (1) |

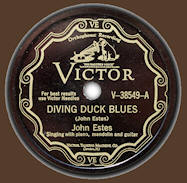

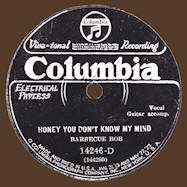

Jefferson's

remake some four or five months later was virtually identical with the

added dark 'tolling' noted on the lower strings of his guitar following

the lines in verse 7: "Have you heard a church bell tone?" This song was

to be Subsequently 'covered' by many singers; sometimes called "Two

White Horses in A Line" or, "One Kind Favor." Under the former title, it

was recorded in 1931 by 'The Two Poor boys' on guitar and mandolin,

while in 1942, the melody had been used on an unrelated Mississippi

blues title, "County Farm Blues" by Son House, who claimed, after his

'rediscovery ' over 20 years later, to have recorded the Blind Lemon

title in 1930, but it was never issued. Jefferson's

remake some four or five months later was virtually identical with the

added dark 'tolling' noted on the lower strings of his guitar following

the lines in verse 7: "Have you heard a church bell tone?" This song was

to be Subsequently 'covered' by many singers; sometimes called "Two

White Horses in A Line" or, "One Kind Favor." Under the former title, it

was recorded in 1931 by 'The Two Poor boys' on guitar and mandolin,

while in 1942, the melody had been used on an unrelated Mississippi

blues title, "County Farm Blues" by Son House, who claimed, after his

'rediscovery ' over 20 years later, to have recorded the Blind Lemon

title in 1930, but it was never issued.

In 1942 Son House had

recorded for the Library of Congress as opposed to a commercial record

label, and it was for the Library that Texan Pete Harris performed his

own version of "Grave" which he called "Blind Lemon's Song" in 1934.

Again for the Library, some five years later, fellow Texas guitarist,

Smith Casey put "Two White Horses Standin' In A Line" on wax. All these

versions, except the unissued Son House side, follow Lemon's original

"Grave" with one or two variations but including all of his verses. (see

Table 'B')

Table 'B'

|

Title |

Artist |

Artist's State

of Origin |

Date / Location

|

|

1. |

"See That My Grave's

Kept Clean" |

Blind Lemon Jefferson

|

Texas |

c.-/10/27

Chicago

|

|

2. |

"See That My Grave Is

Kept Clean" |

Blind Lemon Jefferson

|

Texas |

-/2/28

Chicago

|

|

3. |

"See That my Grave Is

Kept Clean" |

Son House |

Mississippi |

28/5/30

Grafton

|

|

4. |

"Two White Horses In A

Line" |

The Two Poor Boys |

Alabama |

20/5/31

N.Y.C.

|

|

5. |

"Blind Lemon's Song" |

Pete Harris |

Texas |

-/5/34 Richmond, TX

|

|

6. |

"Two White Horses

Standin' In A Line" |

Smith Casey |

Texas |

16/4/39

Brazoria, TX

|

An informant from the

University of North Carolina in 1975 gave the Following details on the

origin of "Grave" to John Cowley, saying that the song is "... an

amalgamation of several earlier songs, amongst them Old Blue (or Old

Veen) 'Stormalong' (a nineteenth century sea shanty) and a number of

spirituals." (2). One spiritual recorded in 1938 in South Carolina

included the lines:

"You can dig my grave

with a silver spade,

You can let me down with a golden chain,

Then you gonna hear my coffin sound,

Then you know you ain't see my face no more." (3)

While a songster from

Hernando, Mississippi, Jim Jackson included the spade/chain motif in the

"praise-song to the hunting dog" (4):

"When Old Blue died and

I dug his grave,

I dug his grave with a silver spade,

I let him down with a golden chain,

And every link I called his name,

Go on Blue, you good dog you." (x2) (5)

The shanty referred to, 'Stormalong'

runs:

| |

1. |

"0 Stormy, he is

dead and gone;

To my way, you storm along,

0 Stormy was a good old man;

Ay, ay ay, Mister Stormalong."

|

| |

2. |

"We'll dig his

grave with a silver spade,

To my way, you storm along,

And Lower Him Down With A Golden Chain.

Ay, ay, ay, Mister Stormalong."

|

| |

3. |

"I wish I was Old

Stormy's son,

To my way, you storm along,

I'd build a ship of a thousand ton.

Ay, ay, ay, Mister Stormalong."

|

| |

4. |

"I'd fill her with

New England rum,

To my way, you storm along,

And all my shell-backs, they'de have some.

Ay, ay, ay, Mister Stormalong."

|

| |

5. |

"0 Stormy's dead

and gone to rest,

To my way, you storm along,

Of all the sailors he was best.

Ay, ay, ay, Mister Stormalong." (6) |

Known by other titles such

as "Mister Stormalong" & "Captain Stormalong", this shanty can be traced

back to the 1830's and 40's, and includes the following verse variants:

| |

2. |

"We'll dig his

grave with a silver spade.

His shroud of finest silk was made."

"We lowered him down with a golden chain,

Our eyes all dim with more than rain." (7) |

Hugill has no doubt that 'Stormalong'

is of Negro origin. Verse 5. above is found in another shanty "Storm

Along John" also known as "Stormalong-John", "Come Along", "Git-along",

"Way Stormalong, John", and several other shanties quoted. From Nordoff

he gives the following:

| |

|

"Lower him down

with a golden chain, |

|

Chorus: |

|

Carry him along,

boys, carry him along,

Then he'll never rise again. |

|

Chorus: |

|

Carry him to the

burying ground. |

|

Grand Chorus: |

|

'Way-oh-way-oh-way

- storm along,

'Way-you rolling crew, storm along stormy." (8) |

The spade/chain motif occurs

in another shanty known variously as "Santiana", "The Plains O'Mexico"

or "Old Santy Ana" :

|

Verse 16 |

|

"We'll dig his

grave with a silver spade,

An' mark the spot where he was laid." (9) |

It would appear that the

"silver spade/golden chain" verses were strongly extant in the

nineteenth century around the Gulf ports particularly, as Hugill seems

to favour them as place of origin and that would include Mobile,

Galveston, Houston, etc. all of which had a healthy Blues tradition.

Maybe a young Lemon Jefferson learnt his "Grave" from part slave-song

and part sea shanty.

In any event the sailor who

was the subject of the above shanties, very popular by all accounts,

caused speculation as to who was the original 'Mr. Stormalong'. "One

authority insists that he was, in fact, John Willis - a famous

early-Victorian ship master and owner whose son was also called John

Willis and owned the famous "Cutty Sark" (10).

Verses 3 & 4 of "Stormalong"

allude to a ship-owner, at least. Of course it was the second verse that

captured the imagination of the Blues singer.

Cowley's informant, referred

to earlier was actually Dan Patterson the Folklore Professor at the

University of North Carolina in 1975. Patterson presented a good case

for the origin of "Grave" in the shape of the spiritual, citing several

examples which included the "spade/chain" motif. This is further

supported by an observation in 1867 by one Thomas Wentworth Higginson

who noted a "Negro spiritual" called "In The Morning" :

"Dere's a silver spade

for to dig my grave

And a golden chain to let me down.

Don't you hear de trumpet sound?

In de mornin',

In de mornin',

Chil'en? Yes, my lord!

Don't you hear de trumpet sound?" (11)

Jackson muses "These golden

and silver fancies remind one of the King of Spain's daughter in "Mother

Goose", and the golden apple and the silver pear, which are doubtless

themselves but the vestiges of some simple early composition like this."

(12). The silver/gold images featured in fairy stories, English

folksongs and ballads generally from Britain and the U.S.A. For example,

the golden ball in "The Prickly Bush" which reappeared in the famous

Texas Blues folk singer Leadbelly's repertoire as "The Gallis Pole"

amongst other titles (see "British

Colloquial Links And The Blues"),

and "The Silver Pin" which was part of the inspiration for a blues by

Memphis Minnie and erstwhile husband, Kansas Joe in 1930 (see

"British

Colloquial Links And The Blues").

"Pin" is an English folksong of uncertain date, possibly early

nineteenth century; while "The Prickly Bush" also known as "The Maid

Freed From The Gallows" is a ballad which was known in England and the

European continent from the fifteenth century.

Referring to Blind Lemon's

"See That My Grave Is Kept Clean" as "One Kind Favor", Courlander says

"It contains some of the familiar imagery of Anglo-American balladry -

"two white horses in a line", digging a grave with a silver spade, and

lowering the coffin with a golden chain." (13). Roberts agrees that "The

silver spade and golden chain are originally British in various forms."

(14). But adds "The white horses might be an image from either

tradition, though I suspect a thorough working over of an old ballad

image." (15). Roberts continues "Besides the few songs that have been

transferred wholesale, British balladry seems to have influenced black

forms and imagery enduringly. The structure of the blues song "Two White

Horses", with its first line repeated three times (not two as in the

majority of blues), is quite common in both black and white music of the

South." (16). He suggests that many of the images could have come from

early ballads in the British Isles.

Patterson on the other hand

thinks that the "two white horses" image goes back to Biblical origins

while "He traces the silver spade/golden chain imagery back through Old

Blue and the 19th century sea-shanty Stormalong to the old British song

"Who Killed Cock Robin?" " (17). Part of the latter English "nursery

song" which has fourteen verses! has a reference to the origins of Blind

Lemon's blues:

| |

4. |

"Who'll make the shroud?

I,

said the Beetle,

With my thread and needle,

I'll make the shroud.

|

| |

5. |

"Who'll dig his grave?

I,

said the Owl,

With my pick and shovel,

I'll dig his grave."

|

| |

8. |

"Who'll carry the link?

I, said the Linnet,

I'll fetch it in a minute,

I'll carry the link."

|

| |

10. |

"Who'll carry the coffin?

I,

said the Kite,

If it's not-through the

night,

I'll carry the coffin."

|

| |

11. |

"Who'll bear the pall?

We

said the Wren,

Both the cock and hen,

We'll

bear the pall."

|

| |

13. |

"Who'll toll the bell?

I, said the Bull,

Because I can pull,

I'll toll the bell." (18) |

Harrowven says "There is a

strong belief, especially in the West Country, that the nursery song

'Who Killed Cock Robin?" is a direct dramatization of the death of

William Rufus." (19), otherwise William II. This would place the date at

the beginning of the twelfth century when Henry I was crowned.

Although no reference is

made to silver or gold in this nursery rhyme, it could nevertheless have

formed the basis of "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean". Such a basis is

captured in a song by the finest of the Georgia Bluesmen, Blind Willie

McTell, who concluded his "Lay Some Flowers On My Grave" with these two

verses:

| |

|

"Now when I'm gone to come

no more,

An' all pallbearers lay me low.

When you hear that coffin

sound,

You know McTell's in the ground, |

| |

Ref: |

Hot mama, lay some

flowers on my grave".

|

| |

|

"Now when the poor boy's

dead an' gone,

I'm left in this old world all alone.

When you hear the church

bell tone,

You know McTell's dead an'

gone, |

| |

Ref : |

Hot mama, lay some

flowers on my grave." (20) |

Interestingly, the

silver/gold element could have 'Cock Robin' connections too, via another

nursery rhyme "Ride A Cock-Horse To Banbury Cross". The lady of the

latter wearing presumably gold rings "on her fingers" and silver "bells

on her toes". In the early 19th c. a book publisher, J.G. Rusher,

printed several nursery rhymes about Banbury, in the form of chapbooks.

Harrowven tells us "... the earliest must have been published around the

year 1810." (21). She notes that "Many have been reprinted by Anne and

Peter Stockham and on the back of "Death and Burial of Cock Robin",

Rusher added this verse:

| |

"Ride on a horse,

To Banbury Cross.

To Cock Robin's grave,

On a galloping horse." (22) |

It was at the outset of the

nineteenth century when "... black church music ... metamorphosed into

'negro spirituals'". (23). In 1794, Richard Allen, born a slave,

inaugurated his church, the beginning of the "... influential African

Methodist Episcopal Church entirely separate from the white Methodist

Church." (24). The spirituals then became 'Afro-Americanised.' Although

the hymns utilized by the slaves, at that time still drew largely from

Dr. Isaac Watts' (the English Nonconformist minister) publication of

"Hymns and Spiritual Songs", they added their own choruses,

verses, stanzas or refrains and increasingly, joined them to the old

African pentatonic (5-note) scale, sometimes adding the 'flatted

seventh' - that peculiarly Afro-American note of melancholy which also characterised the secular blues." (25)

However, these new 'negro

spirituals' also drew on images outside their U.S. environment, such as

the silver spade/golden chain motif. One such title, although it doesn't

mention spades or chains, could be "Oh Link, Oh Link" recorded by the

Evening Four in Charlotte, North Carolina on 16th. February, 1937. A

rough chronology of 'See That My Grave Is Kept Clean" is shown in Table

'C'.

Table 'C'

| Title |

Singer /

Author |

Date /

Location |

Possible

Route

|

| 1. |

WHO KILLED

COCK ROBIN? |

? |

c. 1100.

England |

Oral

transmission to early British ballad singers.

|

| 2. |

RIDE A

COCK-HORSE TO BANBURY CROSS |

? |

Unk.date,

England

|

See above |

| 3. |

THE PRICKLY

BUSH/

THE MAID FREED FROM THE

GALLOWS

|

? |

15th c.

England/Europe |

See above |

| 4. |

STORMALONG/MISTER

STORMALONG/CAPTAIN

STORMALONG/COME ALONG/

SANTIANA, etc. |

? |

c. 1830's

On board U.K./U.S. ships |

Oral transmission

to & from sailors

& black dockworkers

|

| 5. |

OLD BLUE |

? |

19th. c

Southern

U.S. |

Oral transmission from white

to black rural

singers.

|

| 6. |

SILVER PIN |

? |

early 19th c. England |

Oral transmissions from

ballad singers to shanty men & workers at Gulf Ports.

|

| 7. |

IN THE

MORNING |

? |

1867.

Southern U.S. |

Oral transmission to travelling songsters & black dock workers at

Gulf Ports.

|

| 8. |

SEE THAT MY GRAVE'S

KEPT CLEAN |

Blind Lemon Jefferson |

c. -/10/27.

Chicago |

Oral transmission from Gulf Ports.

|

| 9. |

OLD DOG BLUE |

Jim Jackson |

2/2/28.

Memphis |

Oral transmissions from

travelling medicine shows and Gulf Ports.

|

| 10. |

LAY SOME FLOWERS ON MY GRAVE |

Blind Willie Mctell

|

25/4/35.

Chicago |

Oral transmissions from Gulf

Ports/ Lemon's recordings.

|

| 11. |

OH LINK, OH LINK. |

Evening Four |

16/2/37.

Charlotte, N.C. |

Oral transmissions from earlier sacred singers & records?

|

| 12. |

MAYBE THE LAST TIME |

Eagle Jubilee Four. |

4/11/38.

Columbia, S. C.

|

As

above |

Intriguingly, Jim Jackson

had recorded an earlier version of "Old Dog Blue" at the same time as

Blind Lemon cut his first version of "Grave", i.e. October, 1927.

Although it remained unissued. It seems obvious that the main influence

on Lemon's blues was the group of sea shanties revolving around

"Stormalong" which passed freely between American and English sailors.

There were other methods of oral transmission, as have been noted but

the central one is the series of seaports dotted along the Eastern

Seaboard of the United States. The earliest roots of "Grave"

could be argued, are English nursery rhymes as far back as the 12th

century, these are now, at best, vestigial and obscured. The most

important, and most recent are the sea shanties; whether directly from

Gulf ports and wandering Blues singers or indirectly from black

stevedores who passed songs on to religious singers, who in turn

incorporated phrases into their spirituals and gospel numbers, from

whence Lemon derived the lyrics for "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean". Intriguingly, Jim Jackson

had recorded an earlier version of "Old Dog Blue" at the same time as

Blind Lemon cut his first version of "Grave", i.e. October, 1927.

Although it remained unissued. It seems obvious that the main influence

on Lemon's blues was the group of sea shanties revolving around

"Stormalong" which passed freely between American and English sailors.

There were other methods of oral transmission, as have been noted but

the central one is the series of seaports dotted along the Eastern

Seaboard of the United States. The earliest roots of "Grave"

could be argued, are English nursery rhymes as far back as the 12th

century, these are now, at best, vestigial and obscured. The most

important, and most recent are the sea shanties; whether directly from

Gulf ports and wandering Blues singers or indirectly from black

stevedores who passed songs on to religious singers, who in turn

incorporated phrases into their spirituals and gospel numbers, from

whence Lemon derived the lyrics for "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean".

© Copyright 1991 Max Haymes.

All Rights Reserved.

__________________________________________________________________________

Notes:

| 1. |

Jefferson. L.

|

| 2. |

Cowley J. p.4.

|

| 3. |

Eagle Jubilee Four.

|

| 4. |

Oliver P. p.248. "Songsters

etc.

|

| 5. |

Ibid

|

| 6. |

Baker & Miall. Ibid.

p.p.227-228

|

| 7. |

Hugill. ibid. p.68.

|

| 8. |

Ibid. p.72.

|

| 9. |

Ibid p.77.

|

| 10. |

Baker & Miall. ibid. p.228.

|

| 11. |

Jackson. ibid. p.95.

|

| 12. |

Ibid.

|

| 13. |

Courlander H. p.139.

|

| 14. |

Roberts J. S. p. 156.

|

| 15. |

Ibid.

|

| 16. |

Ibid.

|

| 17. |

Groom B. p.2.

|

| 18. |

Harrowven J. p. p. 93-94.

|

| 19. |

Ibid. p.93.

|

| 20. |

McTell. W.

|

| 21. |

Harrowven. ibid p.168.

|

| 22. |

Ibid.

|

| 23. |

Broughton V. p. 20.

|

| 24. |

Ibid.

|

| 25. |

Ibid. |

__________________________________________________________________________

Back

to essay overview

__________________________________________________________________________

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved.

Essay (this page) ©

Copyright 1991 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

For further information please email:

alan.white@earlyblues.com

Check out other essays here:

|

Jefferson's

remake some four or five months later was virtually identical with the

added dark 'tolling' noted on the lower strings of his guitar following

the lines in verse 7: "Have you heard a church bell tone?" This song was

to be Subsequently 'covered' by many singers; sometimes called "Two

White Horses in A Line" or, "One Kind Favor." Under the former title, it

was recorded in 1931 by 'The Two Poor boys' on guitar and mandolin,

while in 1942, the melody had been used on an unrelated Mississippi

blues title, "County Farm Blues" by Son House, who claimed, after his

'rediscovery ' over 20 years later, to have recorded the Blind Lemon

title in 1930, but it was never issued.

Jefferson's

remake some four or five months later was virtually identical with the

added dark 'tolling' noted on the lower strings of his guitar following

the lines in verse 7: "Have you heard a church bell tone?" This song was

to be Subsequently 'covered' by many singers; sometimes called "Two

White Horses in A Line" or, "One Kind Favor." Under the former title, it

was recorded in 1931 by 'The Two Poor boys' on guitar and mandolin,

while in 1942, the melody had been used on an unrelated Mississippi

blues title, "County Farm Blues" by Son House, who claimed, after his

'rediscovery ' over 20 years later, to have recorded the Blind Lemon

title in 1930, but it was never issued. Intriguingly, Jim Jackson

had recorded an earlier version of "Old Dog Blue" at the same time as

Blind Lemon cut his first version of "Grave", i.e. October, 1927.

Although it remained unissued. It seems obvious that the main influence

on Lemon's blues was the group of sea shanties revolving around

"Stormalong" which passed freely between American and English sailors.

There were other methods of oral transmission, as have been noted but

the central one is the series of seaports dotted along the Eastern

Seaboard of the United States. The earliest roots of "Grave"

could be argued, are English nursery rhymes as far back as the 12th

century, these are now, at best, vestigial and obscured. The most

important, and most recent are the sea shanties; whether directly from

Gulf ports and wandering Blues singers or indirectly from black

stevedores who passed songs on to religious singers, who in turn

incorporated phrases into their spirituals and gospel numbers, from

whence Lemon derived the lyrics for "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean".

Intriguingly, Jim Jackson

had recorded an earlier version of "Old Dog Blue" at the same time as

Blind Lemon cut his first version of "Grave", i.e. October, 1927.

Although it remained unissued. It seems obvious that the main influence

on Lemon's blues was the group of sea shanties revolving around

"Stormalong" which passed freely between American and English sailors.

There were other methods of oral transmission, as have been noted but

the central one is the series of seaports dotted along the Eastern

Seaboard of the United States. The earliest roots of "Grave"

could be argued, are English nursery rhymes as far back as the 12th

century, these are now, at best, vestigial and obscured. The most

important, and most recent are the sea shanties; whether directly from

Gulf ports and wandering Blues singers or indirectly from black

stevedores who passed songs on to religious singers, who in turn

incorporated phrases into their spirituals and gospel numbers, from

whence Lemon derived the lyrics for "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean".